Heritage Education for Sustainable Development: Dialogue with Indigenous Communities in Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethnomusicology a Very Short Introduction

ETHNOMUSICOLOGY A VERY SHORT INTRODUCTION Thimoty Rice Sumário Chapter 1 – Defining ethnomusicology...........................................................................................4 Ethnos..........................................................................................................................................5 Mousikē.......................................................................................................................................5 Logos...........................................................................................................................................7 Chapter 2 A bit of history.................................................................................................................9 Ancient and medieval precursors................................................................................................9 Exploration and enlightenment.................................................................................................10 Nationalism, musical folklore, and ethnology..........................................................................10 Early ethnomusicology.............................................................................................................13 “Mature” ethnomusicology.......................................................................................................15 Chapter 3........................................................................................................................................17 Conducting -

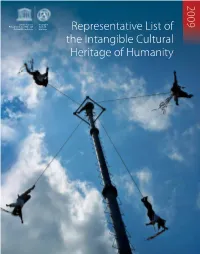

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Of

RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 2 2009 United Nations Intangible Educational, Scientific and Cultural Cultural Organization Heritage Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 5 Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 1 2009 Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 2 © UNESCO/Michel Ravassard Foreword by Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO UNESCO is proud to launch this much-awaited series of publications devoted to three key components of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage: the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding, the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and the Register of Good Safeguarding Practices. The publication of these first three books attests to the fact that the 2003 Convention has now reached the crucial operational phase. The successful implementation of this ground-breaking legal instrument remains one of UNESCO’s priority actions, and one to which I am firmly committed. In 2008, before my election as Director-General of UNESCO, I had the privilege of chairing one of the sessions of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, in Sofia, Bulgaria. This enriching experience reinforced my personal convictions regarding the significance of intangible cultural heritage, its fragility, and the urgent need to safeguard it for future generations. Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 3 It is most encouraging to note that since the adoption of the Convention in 2003, the term ‘intangible cultural heritage’ has become more familiar thanks largely to the efforts of UNESCO and its partners worldwide. -

Society for Ethnomusicology 59Th Annual Meeting, 2014 Abstracts

Society for Ethnomusicology 59th Annual Meeting, 2014 Abstracts Young Tradition Bearers: The Transmission of Liturgical Chant at an then forms a prism through which to rethink the dialectics of the amateur in Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church in Seattle music-making in general. If 'the amateur' is ambiguous and contested, I argue David Aarons, University of Washington that State sponsorship is also paradoxical. Does it indeed function here as a 'redemption of the mundane' (Biancorosso 2004), a societal-level positioning “My children know it better than me,” says a first generation immigrant at the gesture validating the musical tastes and moral unassailability of baby- Holy Trinity Eritrean Orthodox Church in Seattle. This statement reflects a boomer retirees? Or is support for amateur practice merely self-interested, phenomenon among Eritrean immigrants in Seattle, whereby second and fails to fully counteract other matrices of value-formation, thereby also generation youth are taught ancient liturgical melodies and texts that their limiting potentially empowering impacts in economies of musical and symbolic parents never learned in Eritrea due to socio-political unrest. The liturgy is capital? chanted entirely in Ge'ez, an ecclesiastical language and an ancient musical mode, one difficult to learn and perform, yet its proper rendering is pivotal to Emotion and Temporality in WWII Musical Commemorations in the integrity of the worship (Shelemay, Jeffery, Monson, 1993). Building on Kazakhstan Shelemay's (2009) study of Ethiopian immigrants in the U.S. and the Margarethe Adams, Stony Brook University transmission of liturgical chant, I focus on a Seattle Eritrean community whose traditions, though rooted in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, are The social and felt experience of time informs the way we construct and affected by Eritrea's turbulent history with Ethiopia. -

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity As Heritage Fund

ElemeNts iNsCriBed iN 2012 oN the UrGeNt saFeguarding List, the represeNtatiVe List iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL HERITAGe aNd the reGister oF Best saFeguarding praCtiCes What is it? UNESCo’s ROLe iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL SECRETARIAT Intangible cultural heritage includes practices, representations, Since its adoption by the 32nd session of the General Conference in HERITAGe FUNd oF THE CoNVeNTION expressions, knowledge and know-how that communities recognize 2003, the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural The Fund for the Safeguarding of the The List of elements of intangible cultural as part of their cultural heritage. Passed down from generation to Heritage has experienced an extremely rapid ratification, with over Intangible Cultural Heritage can contribute heritage is updated every year by the generation, it is constantly recreated by communities in response to 150 States Parties in the less than 10 years of its existence. In line with financially and technically to State Intangible Cultural Heritage Section. their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, the Convention’s primary objective – to safeguard intangible cultural safeguarding measures. If you would like If you would like to receive more information to participate, please send a contribution. about the 2003 Convention for the providing them with a sense of identity and continuity. heritage – the UNESCO Secretariat has devised a global capacity- Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural building strategy that helps states worldwide, first, to create -

Decisions Paris, 7 December 2012 Original: English/French

7 COM ITH/12/7.COM/Decisions Paris, 7 December 2012 Original: English/French CONVENTION FOR THE SAFEGUARDING OF THE INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE INTERGOVERNMENTAL COMMITTEE FOR THE SAFEGUARDING OF THE INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE Seventh session UNESCO Headquarters, Paris 3 to 7 December 2012 DECISIONS ITH/12/7.COM/Decisions – page 2 DECISION 7.COM 2 The Committee, 1. Having examined document ITH/12/7.COM/2 Rev., 2. Adopts the agenda of its seventh session as annexed to this Decision. Agenda of the seventh session of the Committee 1. Opening of the session 2. Adoption of the agenda of the seventh session of the Committee 3. Replacement of the rapporteur 4. Admission of observers 5. Adoption of the summary records of the sixth ordinary session and fourth extraordinary session of the Committee 6. Examination of the reports of States Parties on the implementation of the Convention and on the current status of elements inscribed on the Representative List 7. Report of the Consultative Body on its work in 2012 8. Examination of nominations for inscription in 2012 on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding 9. Examination of proposals for selection in 2012 to the Register of Best Safeguarding Practices 10. Examination of International Assistance requests greater than US$25,000 11. Report of the Subsidiary Body on its work in 2012 and examination of nominations for inscription in 2012 on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity 12. Questions concerning the 2013, 2014 and 2015 examination cycles a. System of rotation for the members of the Consultative Body b. -

Consolidated List of Abstracts (AAWM

ABSTRACTS Keynote Addresses Music Analysis and Ethnomusicology: some reflections on rhythmic theory Martin Clayton Durham University, UK If these are interesting times for the relationship between ethnomusicology and music analysis, then this is particularly true in the area of rhythmic and metrical theory. On the one hand, time seems to be more amenable than many other dimensions of music to cross-cultural comparison; indeed, recent work in the (traditionally Western-art-music focused) discipline of ‘music theory’ develops a set of concepts that appear to be generalizable across a wide array of musical traditions. At the same time, ethnomusicology’s history of theorising rhythm, especially in Africa, has acted as a lightning rod for heated criticism of the discipline. Ethnomusicology’s relationship to rhythmic theory appears to be at the same time full of potential and deeply problematic. In this paper I will reflect on some of the issues raised by theorising and analysing musical time cross- culturally, both now and in the past. What principles allow us to continue to develop general theories of rhythm and metre, and what – apart from reflecting on the enormous diversity of musical practice and theory around the world – does a historically self-aware ethnomusicology have to offer that project? Music, Identity Politics, and the Clever Boy from Croydon Nicholas Cook University of Cambridge, UK Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912)—in Elgar’s equivocal term the ‘clever boy’ from Croydon— was discovered by the Royal College of Music set at an early age, and his Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, completed when the composer was 23, was one of the great commercial successes of its time. -

Making Community Forests Work for Local and Indigenous Communities in the Central African Republic: Anthropological Perspectives on Strategies for Intervention

MAKING COMMUNITY FORESTS WORK FOR LOCAL AND INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES IN THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC: ANTHROPOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES ON STRATEGIES FOR INTERVENTION Robert E. Moïse in collaboration with Marjolaine Pichon May 2019 PART OF THE UNDER THE CANOPY SERIES CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS 1 GLOSSARY 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1. INTRODUCTION 8 2. GOALS AND CHALLENGES OF COMMUNITY FORESTRY 12 3 WHY COMMUNITY FORESTRY EFFORTS HAVE FAILED TO ACHIEVE THEIR GOALS: THE CASE OF CAMEROON 15 4. CULTURAL AND HISTORICAL CONTEXTS FOR COMMUNITY FORESTRY IN CAR 17 The Land: Customary Forest Management 17 The Historical Context: Relations between Bantu and indigenous peoples 20 The People: Customary Social Organisation 22 Politics: Decision-making, Leadership and Customary ‘Democracy’ 26 5. LEVERAGING CUSTOMARY INSTITUTIONS TO CREATE SUCCESSFUL COMMUNITY FORESTRY 29 Promoting Sustainable Management 29 Making Community Forestry ‘Community-Friendly’ 31 Facilitating Sustainable Commercialisation 33 Protecting Indigenous Rights and Facilitating Indigenous Participation 34 6. AREAS REQUIRING ADDITIONAL SUPPORT 37 7. RECOMMENDATIONS 38 REFERENCES 40 LIST OF ACRONYMS CAR Central African Republic CdG Comité de Gestion (Management Committee) CSO Civil Society Organisation DfID Department for International Development (British government) DRC Democratic Republic of Congo FPIC Free, Prior and Informed Consent IP Indigenous People MEFP Maison de l’Enfant et de la Femme Pygmées NTFP Non-Timber Forest Product PA Protected Area RFUK Rainforest Foundation United Kingdom UNDRIP United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 1 GLOSSARY Anthropological terms • Bayaka: also referred to as ‘Aka’, they are the most numerous of the three indigenous groups living in the forest areas of southwestern CAR. Since all our indigenous respondents were Bayaka, we also use it as a more general term for the indigenous peoples of the southwest. -

Marie-Theres Albert / Anca Claudia Prodan

Marie-Theres Albert / Anca Claudia Prodan Intangible Cultural Heritage – From the Development of a Concept to the Protection of Cultural Diversity Series of Lectures of the Institute Heritage Studies (IHS) - Guest lecture at the Beijing Institute of Technology (BIT) March 2019 Prof. Dr. Marie-Theres Albert Chair Intercultural Studies, UNESCO Chair in Heritage Studies Series of lectures of the IHS 2 Global communication and information systems have changed the industrial development with their streams of capital and goods Crac des Chevaliers and Qal’at Communication and Salah El-Din, Syrian Arab Republic information around the globe affected both Globalization is a result of the directly and indirectly ‘Third Industrial Revolution’ the cultures of the world Due to globalization, the safeguarding of intangible heritage has The global changes have changed the become an urgent need approaches towards intangible heritage and its meaning for cultural identities Prof. Dr. Marie-Theres Albert Director Institute Heritage Studies Series of lectures of the IHS 3 culture gives mankind the ability to reflect upon itself 1982 Tassili n'Ajjer, Algeria The Mexico City Declaration on Cultural Policies “in its widest sense, culture may now be said to be the whole complex of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features that characterize a society or social group. It includes not only the arts and letters, but also modes of life, the fundamental rights of the human being, culture makes us value systems, traditions and beliefs” man expresses specifically human, himself [through culture], rational beings becomes aware of himself, recognizes his incompleteness, questions his own achievements, seeks untiringly for new through culture we discern meanings and creates works values and make choices through which he transcends his limitations Prof. -

XXVIII PÄRNU INTERNATIONAL DOCUMENTARY and ANTHROPOLOGY FILM FESTIVAL in Pärnu, Haapsalu, Elva, Viljandi, Heimtali, Manija, Vormsi and on ETV

XXVIII PÄRNU INTERNATIONAL DOCUMENTARY AND ANTHROPOLOGY FILM FESTIVAL in Pärnu, Haapsalu, Elva, Viljandi, Heimtali, Manija, Vormsi and on ETV July 14 - 27, 2014 XXVIII PÄRNU RAHVUSVAHELINE DOKUMENTAAL- JA ANTROPOLOOGIAFILMIDE FESTIVAL Pärnus, Haapsalus, Elvas, Viljandis, Heimtalis, Manijal, Vormsil ja ETV-s 14. - 27. juulil 2014 The festival is supported by the Ministry of Culture of Estonia, Estonian Cultural Endowment, Town of Pärnu, Estonian National Museum, Museum of Heimtali, Museum of New Art, Tallink, Estonian TV Festival toimub tänu Kultuuriministeeriumi, Kultuurkapitali, Pärnu linna, Eesti Rahva Muuseumi, Uue Kunsti Muuseumi, Heimtali Muuseumi, Tallinki ja Eesti Televisiooni toetusele. The directors awarded with the Grand Prize for the best film Festivali parima filmi auhinna - Lääne-Eesti käsitööteki - of the festival - a handwoven West-Estonian blanket: on oma meistriteostega võitnud järgmised režissöörid : 1987 Asen Balikci (Canada) for Winter In Ice Camp 1987 Asen Balikci “Talv jäälaagris” (Kanada) 1988 Jon Jerstad (Norway) for Vidarosen 1988 Jon Jerstad “Vidarosen” (Norra) 1989 Ivars Seleckis (Latvia) for Cross-Street 1989 Ivars Seleckis “Põiktänav” (Läti) 1990 Hugo Zemp (France) for Song of Harmonics 1990 Hugo Zemp “Kõrilaulmine” (Prantsusmaa) 1991 Lise Roos (Denmark) for The Allotment Garden 1991 Lise Roos “Renditud aed” (Taani) 1992 Kari Happonen (Finland) for A Visit 1992 Kari Happonen “Külaskäik” (Soome) 1993 Heimo Lappalainen (Finland) for Taiga Nomads 1993 Heimo Lappalainen “Taiga rändrahvas” (Soome) 1994 Makoto Sato -

Aka As a Contact Language: Sociolinguistic

AKA AS A CONTACT LANGUAGE: SOCIOLINGUISTIC AND GRAMMATICAL EVIDENCE The members of the Committee approve the masters thesis of Daniel Joseph Duke Donald A. Burquest _____________________________________ Supervising Professor Thomas N. Headland _____________________________________ Carol V. McKinney _____________________________________ Copyright © by Daniel Joseph Duke 2001 All Rights Reserved To the Bayaka people and their friends may our circle be unbroken AKA AS A CONTACT LANGUAGE: SOCIOLINGUISTIC AND GRAMMATICAL EVIDENCE by DANIEL JOSEPH DUKE Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN LINGUISTICS THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON August 2001 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The road to finishing this thesis has been a long one, and many people helped me keep going to the end. Some special people helped carry the burden, and some nearly had to carry me. I want to thank everyone who had a part in seeing the work through. Thanks to family and friends who supported and encouraged me. There are some special friends who were very directly involved with the writing of the thesis, and who I’d like to thank particularly. My committee consisted of Dr. Donald A. Burquest, Dr. Thomas N. Headland, and Dr. Carol V. McKinney. Each member put in a tremendous amount of time and effort into the redaction of the text, and each one contributed greatly from his or her specialization: Dr. Burquest in linguistics and African languages, Dr. McKinney in anthropology and African languages, and Dr. Headland in anthropology and hunter-gatherers. The thesis could not have been as ambitious as it was without the dedicated work and wide area or expertise these scholars brought into it. -

FY 2016 Fall Grant Announcement December 8, 2015

FY 2016 Fall Grant Announcement December 8, 2015 State and Jurisdiction List Project details are current as of December 1, 2015. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Included in this document are Art Works and Challenge America grants. All are organized by state/jurisdiction and then by city and then by name of organization. Click the state or jurisdiction below to jump to that area of the document. Alaska Kansas Minnesota Alabama Kentucky Ohio American Samoa Louisiana Oklahoma Arizona Maryland Oregon Arkansas Massachusetts Pennsylvania California Michigan Rhode Island Colorado Minnesota South Carolina Connecticut Mississippi South Dakota Delaware Missouri Tennessee District of Columbia Montana Texas Florida Nebraska Utah Georgia New Hampshire Vermont Guam New Jersey Virginia Hawaii New Mexico Washington Idaho New York West Virginia Illinois North Carolina Wisconsin Indiana North Dakota Wyoming Iowa Michigan Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Arts Endowment approval. Information is current as of December 1, 2015. Page 1 of 243 Alaska Number of Grants: 5 Total Dollar Amount: $82,500 Anchorage Concert Association, Inc. (aka ACA) $25,000 Anchorage, AK FIELD/DISCIPLINE: Presenting & Multidisciplinary Works To support a multidisciplinary presenting series and related activities. ACA will work with community partners to arrange workshops, residencies, house concerts, and other outreach activities. Proposed artists include Dublin Guitar Quartet (Ireland), Afiara Quartet (Canada), and Bela Fleck with Abigail Washburn. Perseverance Theatre, Inc. (aka Perseverance Theatre) $10,000 Douglas, AK FIELD/DISCIPLINE: Theater & Musical Theater To support the production of "Into the Wild," a new rock musical with book by Janet Allard and music and lyrics by Niko Tsakalakos. -

Proposing Strategies Against the Loss of Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Era of Globalization Student Officer: Bill Michalis Position: Chair

Committee: Social, Humanitarian and Cultural Issue: Proposing strategies against the loss of intangible cultural heritage in the era of globalization Student Officer: Bill Michalis Position: Chair Introduction One of the most important aspects of our everyday lives is culture, as it not only concerns each person individually, but also several groups of people as well, either large or small. Culture plays a role in shaping a person’s character. However, culture is not just big monuments and artifacts of historical importance· it is also the tradition behind a civilization, which carves people’s identity. The monuments, the objects, the places are described as Tangible Cultural Heritage. The practices and the traditions are described as Intangible Cultural Heritage and sometimes include objects etc. that are part of the Tangible Cultural Heritage. To understand the importance of preserving the Intangible Cultural Heritage we have to comprehend exactly what it is. Intangible Cultural Heritage is a term that describes anything considered by UNESCO as a part of a nation’s cultural heritage and tradition. It includes any practice that is considered by the people as part of their cultural heritage and it includes any Tangible Cultural Heritage, Figure 1 - The Hat Mon festival at the Hat Mon temple in meaning objects, places, etc. that are Vietnam associated with such practices. In 2001, UNESCO made an effort to define Intangible Cultural Heritage and in 2003, the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (CSICH) was drafted by NGOs and UNESCO member states for the protection and the promotion of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Intangible Cultural Heritage is defined by the 2nd article of the aforementioned Convention as “the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills —as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith— that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage.