Ceremonial Music of Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ryukyuanist a Newsletter on Ryukyu/Okinawa Studies No

The Ryukyuanist A Newsletter on Ryukyu/Okinawa Studies No. 67 Spring 2005 This issue offers further comments on Hosei University’s International Japan-Studies and the role of Ryukyu/Okinawa in it. (For a back story of this genre of Japanese studies, see The Ryukyuanist No. 65.) We then celebrate Professor Robert Garfias’s achievements in ethnomusicology, for which he was honored with the Japanese government’s Order of the Rising Sun. Lastly, Publications XLVIII Hosei University’s Kokusai Nihongaku (International Japan-Studies) and the Ryukyu/Okinawa Factor “Meta science” of Japanese studies, according to the Hosei usage of the term, means studies of non- Japanese scholars’ studies of Japan. The need for such endeavors stems from a shared realization that studies of Japan by Japanese scholars paying little attention to foreign studies of Japan have produced wrong images of “Japan” and “the Japanese” such as ethno-cultural homogeneity of the Japanese inhabiting a certain immutable space since times immemorial. New images now in formation at Hosei emphasize Japan’s historical “internationality” (kokusaisei), ethno-cultural and regional diversity, fungible boundaries, and demographic changes. In addition to the internally diverse Yamato Japanese, there are Ainu and Ryukyuans/Okinawans with their own distinctive cultures. Terms like “Japan” and “the Japanese” have to be inclusive enough to accommodate the evolution of such diversities over time and space. Hosei is a Johnny-come-lately in the field of Japanese studies (Hosei scholars prefer -

The Rise of Nationalism in Millennial Japan

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2010 Politics Shifts Right: The Rise of Nationalism in Millennial Japan Jordan Dickson College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dickson, Jordan, "Politics Shifts Right: The Rise of Nationalism in Millennial Japan" (2010). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 752. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/752 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Politics Shifts Right: The Rise of Nationalism in Millennial Japan A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelors of Arts in Global Studies from The College of William and Mary by Jordan Dickson Accepted for High Honors Professor Rachel DiNitto, Director Professor Hiroshi Kitamura Professor Eric Han 1 Introduction In the 1990s, Japan experienced a series of devastating internal political, economic and social problems that changed the landscape irrevocably. A sense of national panic and crisis was ignited in 1995 when Japan experienced the Great Hanshin earthquake and the Aum Shinrikyō attack, the notorious sarin gas attack in the Tokyo subway. These disasters came on the heels of economic collapse, and the nation seemed to be falling into a downward spiral. The Japanese lamented the decline of traditional values, social hegemony, political awareness and engagement. -

“PRESENCE” of JAPAN in KOREA's POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Ju

TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Jung M.A. in Ethnomusicology, Arizona State University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eun-Young Jung It was defended on April 30, 2007 and approved by Richard Smethurst, Professor, Department of History Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Department of Music Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Eun-Young Jung 2007 iii TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE Eun-Young Jung, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Korea’s nationalistic antagonism towards Japan and “things Japanese” has mostly been a response to the colonial annexation by Japan (1910-1945). Despite their close economic relationship since 1965, their conflicting historic and political relationships and deep-seated prejudice against each other have continued. The Korean government’s official ban on the direct import of Japanese cultural products existed until 1997, but various kinds of Japanese cultural products, including popular music, found their way into Korea through various legal and illegal routes and influenced contemporary Korean popular culture. Since 1998, under Korea’s Open- Door Policy, legally available Japanese popular cultural products became widely consumed, especially among young Koreans fascinated by Japan’s quintessentially postmodern popular culture, despite lingering resentments towards Japan. -

The History Problem: the Politics of War

History / Sociology SAITO … CONTINUED FROM FRONT FLAP … HIRO SAITO “Hiro Saito offers a timely and well-researched analysis of East Asia’s never-ending cycle of blame and denial, distortion and obfuscation concerning the region’s shared history of violence and destruction during the first half of the twentieth SEVENTY YEARS is practiced as a collective endeavor by both century. In The History Problem Saito smartly introduces the have passed since the end perpetrators and victims, Saito argues, a res- central ‘us-versus-them’ issues and confronts readers with the of the Asia-Pacific War, yet Japan remains olution of the history problem—and eventual multiple layers that bind the East Asian countries involved embroiled in controversy with its neighbors reconciliation—will finally become possible. to show how these problems are mutually constituted across over the war’s commemoration. Among the THE HISTORY PROBLEM THE HISTORY The History Problem examines a vast borders and generations. He argues that the inextricable many points of contention between Japan, knots that constrain these problems could be less like a hang- corpus of historical material in both English China, and South Korea are interpretations man’s noose and more of a supportive web if there were the and Japanese, offering provocative findings political will to determine the virtues of peaceful coexistence. of the Tokyo War Crimes Trial, apologies and that challenge orthodox explanations. Written Anything less, he explains, follows an increasingly perilous compensation for foreign victims of Japanese in clear and accessible prose, this uniquely path forward on which nationalist impulses are encouraged aggression, prime ministerial visits to the interdisciplinary book will appeal to sociol- to derail cosmopolitan efforts at engagement. -

Folk Music: from Local to National to Global David W

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SOAS Research Online ASHGATE RESEARCH 12 COMPANION Folk music: from local to national to global David W. Hughes 1. Introduction: folk song and folk performing arts When the new word min’yō – literally ‘folk song’ – began to gain currency in Japan in the early twentieth century, many people were slow to grasp its intent. When a ‘min’yō concert’ was advertised in Tokyo in 1920, some people bought tickets expecting to hear the music of the nō theatre, since the character used for -yō (謡) is the same as that for nō singing (utai); others, notably the police, took the element min- (民) in the sense given by the left-wing movement, anticipating a rally singing ‘people’s songs’ (Kikuchi 1980: 43). In 1929 a music critic complained about the song Tōkyō kōshinkyoku (Tokyo March), which he called a min’yō. This was, however, not a ‘folk song’ but a Western-influenced tune written for a film soundtrack, with lyrics replete with trendy English (Kurata 1979: 338). The idea that a term was needed specifically to designate songs of rural pedigree, songs of the ‘folk’, was slow to catch on. In traditional Japan boundaries between rural songs of various sorts and the kinds of popular songs discussed in the preceding chapter were rarely clear. The ‘folk’ themselves had a simple and ancient native term for their ditties: uta, ‘song’; modifiers were prefixed as needed (for exampletaue uta, ‘rice-planting song’).1 The modern concept of ‘the folk’ springs from the German Romantics. -

The Legalization of Hinomaru and Kimigayo As Japan's National Flag

The legalization of Hinomaru and Kimigayo as Japan's national flag and anthem and its connections to the political campaign of "healthy nationalism and internationalism" Marit Bruaset Institutt for østeuropeiske og orientalske studier, Universitetet i Oslo Vår 2003 Introduction The main focus of this thesis is the legalization of Hinomaru and Kimigayo as the national flag and anthem of Japan in 1999 and its connections to what seems to be an atypical Japanese form of postwar nationalism. In the 1980s a campaign headed by among others Prime Minister Nakasone was promoted to increase the pride of the Japanese in their nation and to achieve a “transformation of national consciousness”.1 Its supporters tended to use the term “healthy nationalism and internationalism”. When discussing the legalization of Hinomaru and Kimigayo as the national flag and anthem of Japan, it is necessary to look into the nationalism that became evident in the 1980s and see to what extent the legalization is connected with it. Furthermore we must discuss whether the legalization would have been possible without the emergence of so- called “healthy nationalism and internationalism”. Thus it is first necessary to discuss and try to clarify the confusing terms of “healthy nationalism and patriotism”. Secondly, we must look into why and how the so-called “healthy nationalism and internationalism” occurred and address the question of why its occurrence was controversial. The field of education seems to be the area of Japanese society where the controversy regarding its occurrence was strongest. The Ministry of Education, Monbushō, and the Japan Teachers' Union, Nihon Kyōshokuin Kumiai (hereafter Nikkyōso), were the main opponents struggling over the issue of Hinomaru, and especially Kimigayo, due to its lyrics praising the emperor. -

Imperial-Way

BUDDHISM/ZEN PHILOSOPHY/JAPANESE HISTORY (Continued from front flap) IMPERIAL-WAY ZEN IMPERIAL-WAY Of related The Record of Linji his own argument that Imperial-Way Zen interest Translation and commentary by Ruth Fuller Sasaki During the first half of the twentieth centu- can best be understood as a modern instance Edited by Thomas Yūhō Kirchner ry, Zen Buddhist leaders contributed active- 2008, 520 pages of Buddhism’s traditional role as protector ly to Japanese imperialism, giving rise to Cloth ISBN: 978-0-8248-2821-9 of the realm. Turning to postwar Japan, Ives what has been termed “Imperial-Way Zen” examines the extent to which Zen leaders “This new edition will be the translation of choice for Western Zen communities, (Kōdō Zen). Its foremost critic was priest, have reflected on their wartime political college courses, and all who want to know that the translation they are reading is professor, and activist Ichikawa Hakugen stances and started to construct a critical faithful to the original. Professional scholars of Buddhism will revel in the sheer (1902–1986), who spent the decades follow- wealth of information packed into footnotes and bibliographical notes. Unique Zen social ethic. Finally, he considers the ing Japan’s surrender almost single-hand- among translations of Buddhist texts, the footnotes to the Kirchner edition con- resources Zen might offer its contemporary tain numerous explanations of grammatical constructions. Translators of classi- edly chronicling Zen’s support of Japan’s leaders as they pursue what they themselves cal Chinese will immediately recognize the Kirchner edition constitutes a small imperialist regime and pressing the issue have identified as a pressing task: ensuring handbook of classical and colloquial Chinese grammar. -

Introduction Western Art Music in Japan: a Success Story?

Nineteenth-Century Music Review, 10 (2013), pp 211–222. r Cambridge University Press, 2013 doi:10.1017/S1479409813000232 Introduction Western Art Music in Japan: A Success Story? Margaret Mehl University of Copenhagen Email: [email protected] Japan’s successful modernization on Western premises, in the second half of the nineteenth century, included the introduction and adoption of Western music. So thorough was the appropriation of Western art music that by the mid-twentieth century it had a dominant position comparable to that in the countries of its origin. On a worldwide level, Japan was already a major consumer of Western art music by the 1930s, a fact that is reflected in the number both of gramophone recordings sold in Japan and of leading artists who included Japan on their international tours. After 1945 Japan became an export country for musical instruments, sound technology and even musical pedagogy, in particular the ‘Suzuki Method’ and the Yamaha music schools. Further influence came from the many Japanese musicians active in orchestras and conservatoires around the world. Meanwhile, indigenous music was increasingly marginalized, and today it has a niche existence. Even contemporary popular music owes as much to Western music as to Japanese. Measured against the aims of the government officials who, after the Meiji Restoration of 1868, made the decision to systematically import Western music and disseminate it through the military and the education system, this development can be described as a success. Their decision was motivated not by aesthetic considerations, but by the recognition of music’s functions in the nations of the West, including its role in ceremonies representing the power of the modern nation-state and in contributing to physical, moral and aesthetic education in schools. -

The Concept of 'Ma' and the Music of Toru Takemitsu

THE CONCEPT OF MA AND THE MUSIC OF TAKEMITSU BY JONATHAN LEE CHENETTE GRINNELL COLLEGE, GRINNELL, IA, 1985 Updated recording references VASSAR COLLEGE, POUGHKEEPSIE, NY, 2008 INTRODUCTION The initial problem confronting any investigation of the music of another culture is to understand the aesthetic attitudes which prevail in that culture. In the case of Japan, this task is made easier by the availability for study of a large body of Japanese music in Western styles. By looking at the characteristic ways a Japanese composer handles the familiar materials of Western music, the musician in the West can begin to understand the aesthetic attitudes that underlie Japanese music as a whole. Toru Takemitsu, one of Japan’s leading composers in the Western style, writes music which is structured in cycles on a large and small scale and in which silences and the spatial arrangement of the instruments are often critically important. These attributes reflect the Japanese aesthetic concept of ma. The present study will begin with a discussion of the concept of ma and will then look at three ways in which ma can be manifested in music, calling on examples from the music of Takemitsu. In the end, the discussion of ma will serve as a background for an analysis of Takemitsu’s piano piece, For Away (1973). 1 I. THE CONCEPT OF MA Ma is an everyday word from the Japanese language meaning both space and time as well as a number of different shadings of space and time including the space of rooms to live in and the time of time to spare. -

2Nd Global Conference Music and Nationalism National Anthem Controversy and the ‘Spirit of Language’ Myth in Japan

2nd Global Conference Music and Nationalism National Anthem Controversy and the ‘Spirit of Language’ Myth in Japan Naoko Hosokawa Max Weber Postdoctoral Fellow European University Institute, Florence Email address: [email protected] Abstract This paper will discuss the relationship between the national anthem controversy and the myth of the spirit of language in Japan. Since the end of the Pacific War, the national anthem of Japan, Kimigayo (His Imperial Majesty's Reign), has caused exceptionally fierce controversies in Japan. Those who support the song claim that it is a traditional national anthem sung since the nineteenth century with the lyrics based on a classical waka poem written in the tenth century, while those opposed to it see the lyrics as problematic for their imperialist ideology and association with negative memories of the war. While it is clear that the controversies are mainly based on the political interpretation of the lyrics, the paper will shed light on the myth of the spirit of language, known as kotodama, as a possible explanation for the uncommon intensity of the controversy. The main idea of the myth is that words, pronounced in a certain manner have an impact on reality. Based on this premise, the kotodama myth has been reinterpreted and incorporated into Japanese social and political discourses throughout its history. Placing a particular focus on links between music and the kotodama myth, the paper will suggest that part of the national anthem controversy in Japan can be explained by reference to the discursive use of the myth. Keywords: National anthem, nationalism, Japan, language, myth 1. -

Liner Notes: Aesthetics of Capitalism and Resistance in Contemporary

LINER NOTES: AESTHETICS OF CAPITALISM AND RESISTANCE IN CONTEMPORARY JAPANESE MUSIC A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jillian Marshall December 2018 © 2018, Jillian Marshall LINER NOTES: AESTHETICS OF CAPITALISM AND RESISTANCE IN CONTEMPORARY JAPANESE MUSIC Jillian Marshall, Ph.D. Cornell University 2018 This dissertation hypothesizes that capitalism can be understood as an aesthetic through an examination and comparison of three music life worlds in contemporary Japan: traditional, popular, and underground. Through ethnographic fieldwork-based immersion in each musical world for nearly four years, the research presented here concludes that capitalism’s alienating aesthetic is naturally counteracted by aesthetics of community-based resistance, which blur and re-organize the generic boundaries typically associated with these three musics. By conceptualizing capitalism -- and socio-economics on whole – as an aesthetic, this dissertation ultimately claims an activist stance, showing by way of these rather dramatic case studies the self-destructive nature of capitalistic enterprise, and its effects on musical styles and performance, as well as community and identity in Japan and beyond. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Prior to undertaking doctoral studies in Musicology at Cornell in 2011, Jillian Marshall studied East Asian Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago, where she graduated with double honors. Jillian has also studied with other institutions, notably Princeton University through the Princeton in Beijing Program (PiB, 2007), and Columbia University through the Kyoto Consortium of Japanese Studies at Doshisha University (KCJS, 2012). Her interest in the music of Japan was piqued during her initial two-year tenure in the country, when she worked as a middle school English teacher in a rural fishing village. -

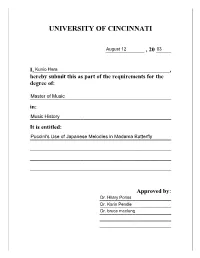

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ PUCCINI’S USE OF JAPANESE MELODIES IN MADAMA BUTTERFLY A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Kunio Hara B.M., University of Cincinnati, 2000 Committee Chair: Dr. Hilary Poriss ABSTRACT One of the more striking aspects of exoticism in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly is the extent to which the composer incorporated Japanese musical material in his score. From the earliest discussion of the work, musicologists have identified many Japanese melodies and musical characteristics that Puccini used in this work. Some have argued that this approach indicates Puccini’s preoccupation with creating an authentic Japanese setting within his opera; others have maintained that Puccini wanted to produce an exotic atmosphere