Risk Factors in Shellfish Harvesting Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013

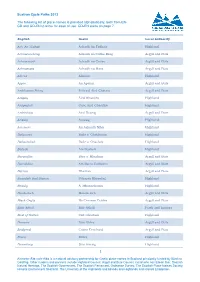

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013 The following list of place-names is provided alphabetically, both from EN- GD and GD-EN to allow for ease of use. GD-EN starts on page 7. English Gaelic Local Authority Ach' An Todhair Achadh An Todhair Highland Achnacreebeag Achadh na Crithe Beag Argyll and Bute Achnacroish Achadh na Croise Argyll and Bute Achnamara Achadh na Mara Argyll and Bute Alness Alanais Highland Appin An Apainn Argyll and Bute Ardchattan Priory Priòraid Àird Chatain Argyll and Bute Ardgay Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardgayhill Cnoc Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardrishaig Àird Driseig Argyll and Bute Arisaig Àrasaig Highland Aviemore An Aghaidh Mhòr Highland Balgowan Baile a' Ghobhainn Highland Ballachulish Baile a' Chaolais Highland Balloch Am Bealach Highland Baravullin Bàrr a' Mhuilinn Argyll and Bute Barcaldine Am Barra Calltainn Argyll and Bute Barran Bharran Argyll and Bute Beasdale Rail Station Stèisean Bhiasdail Highland Beauly A' Mhanachainn Highland Benderloch Meadarloch Argyll and Bute Black Crofts Na Croitean Dubha Argyll and Bute Blair Atholl Blàr Athall Perth and kinross Boat of Garten Coit Ghartain Highland Bonawe Bun Obha Argyll and Bute Bridgend Ceann Drochaid Argyll and Bute Brora Brùra Highland Bunarkaig Bun Airceig Highland 1 Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba is a national advisory partnership for Gaelic place-names in Scotland principally funded by Bòrd na Gaidhlig. Other funders and partners include Highland Council, Argyll and Bute Council, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, Scottish Natural Heritage, The Scottish Government, The Scottish Parliament, Ordnance Survey, The Scottish Place-Names Society, Historic Environment Scotland, The University of the Highlands and Islands and Highlands and Islands Enterprise. -

Loch Etive ICZM Plan

POLICY ZONE B: NORTH CONNEL TO ACHNACREE BAY (CONNEL NARROWS) LANDSCAPE CHARACTERISTICS This zone has a diverse range of adjacent coastal vegetation, including small cultivated fields and woodlands. A well developed hinterland contrasts with the simple uncluttered water surface and largely undeveloped shoreline. Settlement is broadly linear and parallel with the coast throughout the policy zone. SEASCAPE CHARACTERISTICS The seascape is characterised by a narrow elongated fast moving tidal channel, with some subtle bays west of Connel Bridge on the southern side of the Loch. Under the Connel Bridge, the tidal Falls of Lora are recognised as a major natural heritage feature and are a tourist attraction in their own right. Generally the water surface has a feeling of enclosure as the area is contained by low but pronounced slopes and the almost continuous presence of fast moving currents. However, a maritime presence is also reflected in the movement of boats, and the occasional view of open sea. Connel Bridge & Narrows North Connel shoreline looking east to View east to Kilmaronig narrows from Image courtesy of Argyll and Bute Council Connel Bridge Connel Bridge Image courtesy of Argyll and Bute Council Image courtesy of Argyll and Bute Council ACCESS Access can be sought at a number of locations throughout this policy zone. There is good access to Ardmucknish Bay from the pontoon at Camas Bruaich Ruaidhe, although prior permission to use this pontoon must be sought. Access to Falls of Lora is via the two old ferry slipways. The slip at Connel opposite the Oyster Inn has limited car parking facilities and is suitable for shore divers and kayakers, however boats cannot be launched from this slip. -

Loch Awe (Potentially Vulnerable Area 01/34)

Loch Awe (Potentially Vulnerable Area 01/34) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Highland and Argyll Argyll and Bute Council Etive coastal Summary of flooding impacts Summary of flooding impactsSummary At risk of flooding • 20 residential properties • 30 non-residential properties • £100,000 Annual Average Damages (damages by flood source shown left) Summary of objectives to manage flooding Objectives have been set by SEPA and agreed with flood risk management authorities. These are the aims for managing local flood risk. The objectives have been grouped in three main ways: by reducing risk, avoiding increasing risk or accepting risk by maintaining current levels of management. Objectives Many organisations, such as Scottish Water and energy companies, actively maintain and manage their own assets including their risk from flooding. Where known, these actions are described here. Scottish Natural Heritage and Historic Environment Scotland work with site owners to manage flooding where appropriate at designated environmental and/or cultural heritage sites. These actions are not detailed further in the Flood Risk Management Strategies. Summary of actions to manage flooding The actions below have been selected to manage flood risk. Flood Natural flood New flood Community Property level Site protection protection management warning flood action protection plans scheme/works works groups scheme Actions Flood Natural flood Maintain flood Awareness Surface water Emergency protection management warning raising plan/study plans/response study study Maintain flood Strategic Flood Planning Self help Maintenance protection mapping and forecasting policies scheme modelling 357 Section 2 Highland and Argyll Local Plan District Loch Awe (Potentially Vulnerable Area 01/34) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Highland and Argyll Argyll and Bute Council River Awe Background This Potentially Vulnerable Area is The main rivers are the Awe and the located around Loch Awe and includes Orchy. -

Fole Objection

Review of the application and Environmental Statement submitted by Dawnfresh Farming Limited for the formation of fin-fish (Rainbow Trout) farm comprising 10 No. 80m circumference cages plus installation of feed-barge at Sailean Ruadh (Etive 6) Loch Etive, Argyll And Bute (planning ref 13/01379/MFF) Friends of Loch Etive Scottish Charitable Incorporated Organisation SC043986 c/o Muckairn Taynuilt Loch Etive PA35 1JA July 2013 Executive Summary i) Dawnfresh Farming Limited, the rainbow trout fish-farming company, is seeking planning permission to build a massive and permanent floating 10-cage fish-farm at Sailean Ruadh on Loch Etive, effectively doubling the tonnage of rainbow trout as compared to their five existing farms on Loch Etive. ii) While slightly smaller than the original 14-cage application withdrawn in July 2013 following a storm of local protest, the new applications retains most of the features of the earlier application that locals found so objectionable and would be a significant and unacceptable industrialisation of fish-farming activity on Loch Etive. iii) While Dawnfresh had tried to suggest that the initial 14-cage fish-farm application was part of some wider consolidation plan for its sites on Loch Etive as a whole, it has now dropped all pretences to be seeking to reduce its other operations on Loch Etive. Consolidation does not form part of the revised 10-cage application being considered by the Argyll and Bute Council. The proposed fish-farm will effectively double the total tonnage of farmed-fish on Loch Etive, following which Dawnfresh has let slip that it expects the other sites to ‘increase organically over time’, possibly by exploiting recently- granted Permitted Development Rights which allow the addition of extra cages and changes in feed- barges at existing sites without any further public consultation. -

Traces in Scotland of Ancient Water-Lines

TRACES IN SCOTLAND OF ANCIENT WATEE-LINES MARINE, LACOSTRINE, AND FLUVIATILE WITH SOME ACCOUNT OF THE DRIFT MATERIALS ON WHICH THESE TRACES ARE IMPRINTED AND SPECULATIONS REGARDING THE PERIOD IN THE WORLD'S HISTORY TO WHICH THEY MAY BE REFERRED, AND THE CLIMATIC CHANGES THEY SUGGEST BY DAVID MILNE HOME, of Milne Graden, LL.D., F.K.S.E. EDINBURGH DAVID DOUGLAS, CASTLE STREET 1882 SEUL AMD COMPANY, EDINBURGH, GOVERNMENT BOOK ANT) LAW PItTNTKRS FOR SCOTI.ASH. ANCIENT WATER-LINES, fto. INTKODUCTION. Attention has been from time to time drawn to the traces of sea- terraces, more or less horizontal, at various levels. These traces occur in many countries, especially in those bounded by the sea. Dr Chambers, in his "Ancient Sea-Margins," published in the year 1848, gave a list of many in our own country, and he added a notice of some in other countries. So much interested was he in the subject, that not content with a special inspection of the coasts, and also of the valleys of the principal rivers in Scot land, he made a tour round and through many parts of Eng land, and even went to France to visit the valley of the Seine. Dr Chambers had previously been in Norway, and had been much interested in the terraces of the Altenfiord, described first by M. Bravais. He, however, did not confine himself to Europe, — he alluded also in his book to the existence of terraces in North America, as described by Lyell and others. The subject was one which had about the same time begun to engage my own attention ; — as may be seen from references in Dr Chambers' book, to information he obtained from me. -

Iron Making in Argyll

HISTORIC ARGYLL 2009 Iron smelting in Argyll, and the chemistry of the process by Julian Overnell, Kilmore. The history of local iron making, particularly the history of the Bonawe Furnace, is well described in the Historic Scotland publication of Tabraham (2008), and references therein. However, the chemistry of the processes used is not well described, and I hope to redress this here. The iron age started near the beginning of the first millennium BC, and by the end of the first millennium BC sufficient iron was being produced to equip thousands of troops in the Roman army with swords, spears, shovels etc. By then, local iron making was widely distributed around the globe; both local wood for making charcoal, and (in contrast to bronze making) local sources of ore were widely available. The most widely distributed ore was “bog iron ore”. This ore was, and still is, being produced in the following way: Vegetation in stagnant water starts to rot and soon uses up all the available oxygen, and so produces a water at the bottom with no oxygen (anaerobic) which also contains dissolved organic compounds. This solution is capable of slowly leaching iron from the soils beneath to produce a weak solution of dissolved iron (iron in the reduced, ferrous form). Under favourable conditions this solution percolates down until it meets some oxygen (or oxygenated water) at which point the iron precipitates (as the oxidized ferric form). This is bog iron ore and comprises a somewhat ill-defined brown compound called limonite (FeOOH.nH2O), often still associated with particles of sand etc. -

Loch Etive and the Sons of Uisnach

35^ ^'Iv 0^. -t^^ LOCH ETIVE AND THE SONS OF UISNACH. [iiiiiiiiiiiiii|iiiiiiiiiviiPiiHiiiniii|{iiiii! iiii : LOCH ETIVE THE SONS OF ULSNACH WITH ILLUSTRATIONS. iionbon MACMILLAN AND CO. 1&79. The Right of Translation and Re-production Reserved. GLASGOW : PRINTRD AT THE UXIVERSITY PHK r.Y ROnHRT MACI F.iinsK. PREFACE. This book was begun as the work of holidays, and was intended to be read on holidays, but there is not the less a desire to be correct. The primary object is to show what is interesting near Loch Etive, and thus add points of attachment to our country. There is so much that is purely legendary, that it was thought better to treat the subject in a manner which may appear preliminary rather than full, going lightly over a good deal of ground, and, from the very nature of the collected matter, touching on subjects which may at first appear childish. It is believed that to most persons the district spoken of will appear as a newly discovered country, although passed by numer- ous tourists. The landing of the Irish Scots has held a very \-aguc place in our history, and it is interesting to think of them located on a spot which we can visit and to find an ancient account of their King's Court, even if it be only a fanciful one written long after the heroes ceased to live. The connection of Scotland and Ireland, previous to the Irish invasion, is still less known, and to see any mention of the events of the period b\- one who maj' reasonabl\- be supposed to ha\'o spoken in vi PREFACE. -

The Old Schoolhouse - Unique Self Catering Cottages - Pets Welcome - Balmaha

The Old Schoolhouse - Unique Self Catering Cottages - Pets Welcome - Balmaha The Old Schoolhouse - Unique Self Catering Cottages - Pets Welcome - Balmaha Eleanore Nicklin Daytime Phone: 0*7+81295051526354 T*h+e Old0 1S2c3h4o5o6l7h8o9use< M*i+lton 0O1f2 3B4u5c6h7a8n9an D*r+ymen S*t+irlin0g1s2h3i4r5e6 G*6+3 0JE0 Scotland £ 120.00 - £ 293.00 per night A unique collection of four self-catering holiday houses located within the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park. The perfect location for those seeking a tranquil retreat and family/friend gatherings. Facilities: Room Details: COVID-19: Sleeps: 8 Advance booking essential, Capacity limit, COVID-19 measures in place, Pets welcome during COVID-19 restrictions 3 Double Rooms Bathroom: 2 Bathrooms Bath Communications: Wifi Disabled: Ground Floor Bathroom Entertainment: CD \ Music, Satellite, TV Exercise: Jacuzzi / Hot Tub Heat: Central Heating Kitchen: Cooker, Dishwasher, Fridge/Freezer, Grill, Microwave, Oven, Toaster Laundry: Ironing Board \ Iron, Washing Machine Outside Area: Outside Seating, Private Garden, Private Parking © 2021 LovetoEscape.com - Brochure created: 6 October 2021 The Old Schoolhouse - Unique Self Catering Cottages - Pets Welcome - Balmaha Price Included: Electricity and Fuel, Linen, Towels Rooms: Kitchen, Living Room Special: Cots Available, Highchairs Available Standard: Very Good Suitable For: Families, Large Groups, Romantic getaways, Short Breaks, Special Occasions About Drymen and Stirlingshire We are in Milton of Buchanan, near Balmaha, in the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park. Just over a mile from Loch Lomond. Ideal for touring the west coast and highlands. Our cottages are only a 45 minute drive from Glasgow. Nearest Bus Stop: Milton Of Buchanan Nearest Train Station: Balloch Nearest Airport: Glasgow © 2021 LovetoEscape.com - Brochure created: 6 October 2021 The Old Schoolhouse - Unique Self Catering Cottages - Pets Welcome - Balmaha Recommended Attractions 1. -

Download the Full Article As Pdf ⬇︎

shark tales Spurdog in Loch Etive, located near Oban on the west coast of Scotland Text by Lawson Wood Photos Shane Wasik Over a number of years, the actions of fishermen and sea anglers have attracted the attention of marine scientists at the Dunstaffnage Marine Laboratory who quickly became aware of these fishers catching spur- dogs in the Loch Etive area near Oban on the west coast of Scotland. These small sharks were always on a catch-and- release scheme, and The Loch Etive the researchers thought that this little British shark deserved a bit more inter- est in order to discover Spurdogs what they were up to, try- of Scotland ing to learn more about their habitat and habits, and why Loch Etive was so Glen Coe and Glen Etive cradle valley can still only be reached loch (the pier was once used as a This sea loch is one of the most the Firth of Lorn where its dramatic important to the Scottish Loch Etive all the way to the west- on foot, but there is a small and stopping-off point by a small ferry, picturesque sea lochs on the west entrance and exit to the open sea ern shores of Scotland and was rarely-used road that runs most where passengers would disem- coast of Scotland and is around at Connel is framed by the incred- population of these fasci- used as a through-road by our of the way down Glen Etive to bark to a horse and carriage to 27km (17miles) long, starting at the ible Connel Bridge overtopping nating sharks. -

Supplementary Submission from Argyll and Bute Council

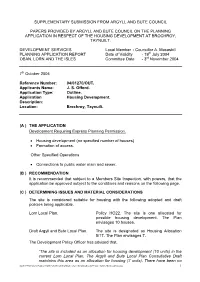

SUPPLEMENTARY SUBMISSION FROM ARGYLL AND BUTE COUNCIL PAPERS PROVIDED BY ARGYLL AND BUTE COUNCIL ON THE PLANNING APPLICATION IN RESPECT OF THE HOUSING DEVELOPMENT AT BROCHROY, TAYNUILT. DEVELOPMENT SERVICES Local Member - Councillor A. Macaskill PLANNING APPLICATION REPORT Date of Validity - 19th July 2004 OBAN, LORN AND THE ISLES Committee Date - 3rd November 2004 7th October 2004 Reference Number: 04/01270/OUT. Applicants Name: J. S. Offord. Application Type: Outline. Application Housing Development. Description: Location: Brochroy, Taynuilt. (A ) THE APPLICATION Development Requiring Express Planning Permission. • Housing development (no specified number of houses) • Formation of access. Other Specified Operations • Connections to public water main and sewer. (B ) RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that subject to a Members Site Inspection, with powers, that the application be approved subject to the conditions and reasons on the following page. (C ) DETERMINING ISSUES AND MATERIAL CONSIDERATIONS The site is considered suitable for housing with the following adopted and draft policies being applicable. Lorn Local Plan. Policy HO22. The site is one allocated for possible housing development. The Plan envisages 10 houses. Draft Argyll and Bute Local Plan. The site is designated as Housing Allocation 5/17. The Plan envisages 7. The Development Policy Officer has advised that, “The site is included as an allocation for housing development (10 units) in the current Lorn Local Plan. The Argyll and Bute Local Plan Consultative Draft maintains this area as an allocation for housing (7 units). There have been no \\EDN-APP-001\USERS\PUBLIC\!WORK PENDING\ENVIRONMENT CROFTING EVIDENCE\SUPP SUB FROM A AND B COUNCIL.DOC 1 timeous objections received in relation to this area as part of the Argyll and Bute Local Plan consultation process. -

Annual Report 2000.Pdf

REPORT AND ACCOUNTS OF The Scottish Association for Marine Science for the period 1 April 1999 to 31 March 2000 The Dunstaffnage Marine Laboratory, Firth of Lorn, with the Laboratory’s larger research vessel Calanus at the pontoon (right). © John Anderson, Highland Image Contents The cold water coral Lophelia - see page 12 for report Director’s introduction 6 Geochemistry North Sea drill cuttings 8 Baltic Sea System Study 9 Restricted Exchange Environments 10 Deep-Sea Benthic Dynamics Deep-Sea macrofauna 11 Cold water coral Lophelia 12 Continental slope environmental assessment 13 Deep-Water Fish Otolith microchemistry 14 West of Scotland angler fish 15 Deep-water elasmobranchs 16 Invertebrate Biology and Mariculture Sea urchin cultivation 17 Bioaccumulation of chemotherapeutants 18 Microalgal dietary supplements 19 Amnesic shellfish poisoning 19 Marine Biotechnology Natural products research 20 Marine carotenoids 21 Microbial ecotoxicology 21 Microbial Ecology Interannual variability in Antarctic waters 22 Coastal waters of Pakistan 23 Zooplankton Dynamics 24 Clyde time-series 25 Modelling vertical migration 25 Active flux 25 Effects of delousing chemicals 26 Marine Biogenic Trace Gases Light and the dimethylsulphide cycle 27 Sediment trap investigations 28 SAMS/UHIp Marine science degree team 29 Phytoplankton and protozoan dynamics 29 Marine geomorphology of Loch Etive 30 Marine Physics 31 Biogeochemistry 32 Report from the SAMS Honorary Fellows Marine ornithology 33 Geology 34 Data Warehouse progress report 35 4 Annual Report 1999-2000 -

Proposal for the Closure of X School

Argyll and Bute Council Customer Services: Education PROPOSAL DOCUMENT: MARCH 2019 Review of Education Provision Ardchattan Primary School Argyll and Bute Council Proposal for the closure of Ardchattan Primary School SUMMARY PROPOSAL It is proposed that education provision at Ardchattan Primary School be discontinued with effect from 21st October 2019. Pupils of Ardchattan Primary School will continue to be educated at Lochnell Primary School. The catchment area of Lochnell Primary School shall be extended to include the current catchment area of Ardchattan Primary School. Reasons for this proposal This is the best option to address the reasons for the proposals which are; Ardchattan Primary School has been mothballed for four years. The school roll is very low and not predicted to rise in the near future. The annual cost of the mothballing of the building is £2,147 Along with several other rural Councils, Argyll and Bute is facing increasing challenges in recruiting staff. At the time of writing there are 14 vacancies for teachers and 2 vacancies for head teachers in Argyll and Bute. Whilst the school is mothballed, the building is deteriorating with limited budges for maintenance. This document has been issued by Argyll and Bute Council in regard to a proposal in terms of the Schools (Consultation) (Scotland) Act 2010 as amended. This document has been prepared by the Council’s Education Service with input from other Council Services. DISTRIBUTION A copy of this document is available on the Argyll and Bute Council website: https://www.argyll-bute.gov.uk/education-and-learning