Iron Making in Argyll

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013

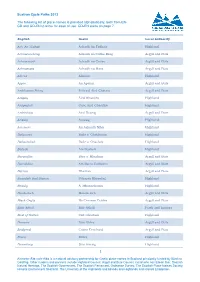

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013 The following list of place-names is provided alphabetically, both from EN- GD and GD-EN to allow for ease of use. GD-EN starts on page 7. English Gaelic Local Authority Ach' An Todhair Achadh An Todhair Highland Achnacreebeag Achadh na Crithe Beag Argyll and Bute Achnacroish Achadh na Croise Argyll and Bute Achnamara Achadh na Mara Argyll and Bute Alness Alanais Highland Appin An Apainn Argyll and Bute Ardchattan Priory Priòraid Àird Chatain Argyll and Bute Ardgay Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardgayhill Cnoc Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardrishaig Àird Driseig Argyll and Bute Arisaig Àrasaig Highland Aviemore An Aghaidh Mhòr Highland Balgowan Baile a' Ghobhainn Highland Ballachulish Baile a' Chaolais Highland Balloch Am Bealach Highland Baravullin Bàrr a' Mhuilinn Argyll and Bute Barcaldine Am Barra Calltainn Argyll and Bute Barran Bharran Argyll and Bute Beasdale Rail Station Stèisean Bhiasdail Highland Beauly A' Mhanachainn Highland Benderloch Meadarloch Argyll and Bute Black Crofts Na Croitean Dubha Argyll and Bute Blair Atholl Blàr Athall Perth and kinross Boat of Garten Coit Ghartain Highland Bonawe Bun Obha Argyll and Bute Bridgend Ceann Drochaid Argyll and Bute Brora Brùra Highland Bunarkaig Bun Airceig Highland 1 Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba is a national advisory partnership for Gaelic place-names in Scotland principally funded by Bòrd na Gaidhlig. Other funders and partners include Highland Council, Argyll and Bute Council, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, Scottish Natural Heritage, The Scottish Government, The Scottish Parliament, Ordnance Survey, The Scottish Place-Names Society, Historic Environment Scotland, The University of the Highlands and Islands and Highlands and Islands Enterprise. -

Stitial Oxide Ions Synthesized by Direct Crystallization

La2Ga3O7.5: a metastable ternary melilite with a super-excess of inter- stitial oxide ions synthesized by direct crystallization of the melt Jintai Fan, Vincent Sarou-Kanian, Xiaoyan Yang, Maria Diaz-Lopez, Franck Fayon, Xiaojun Kuang, Michael Pitcher, Mathieu Allix To cite this version: Jintai Fan, Vincent Sarou-Kanian, Xiaoyan Yang, Maria Diaz-Lopez, Franck Fayon, et al.. La2Ga3O7.5: a metastable ternary melilite with a super-excess of inter- stitial oxide ions synthe- sized by direct crystallization of the melt. Chemistry of Materials, American Chemical Society, 2020, 32 (20), pp.9016-9025. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.0c03441. hal-02959774 HAL Id: hal-02959774 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02959774 Submitted on 7 Oct 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. La2Ga3O7.5: a metastable ternary melilite with a super-excess of inter- stitial oxide ions synthesized by direct crystallization of the melt Jintai Fan,1,2 Vincent Sarou-Kanian,1 Xiaoyan Yang,3 Maria Diaz-Lopez,4,5 Franck Fayon,1 Xiaojun Kuang,3,6 Michael J. Pitcher1* and Mathieu Allix1* 1 CNRS, CEMHTI UPR3079, 45071 Orléans, France 2 Shanghai Institute of Optics and Fine Mechanics, Chinese Academy of Science, Shanghai, 201800, P. -

Ore, Iron, Artefacts and Corrosion

. SERIE C NR 626 AVHANDLINGAR OCH UPPSATSER ARSBOK 61 NR 11 OLOF ARRHENIUS ORE, IRON, ARTEFACTS AND CORROSION WITH 4 PLATES STOCKHOLM 1967 SVERTGES GEOLOGISKA UNDERSOKNING SERIE C NR 626 ARSBOK 6 l NR I I OLOF ARRHENIUS ORE, IRON, ARTEFACTS AND CORROSION WITH 4 PLATES STOCKHOLM 196 7 Contents The conditions of the investigation ....................... Elements on which studies are made. ...................... Methods and sources of material ........................ Conditions of analysis ............................ What ores were first used in the production of iron? ................ The formation, occurrence and chemical composition of limonite ores ........ Synopsis of regions in which lake iron ore has a relatively high frequency of high con- centration of the elements indicated ...................... Rock ores. ................................. Synopsis of regions in which rock ores have a relatively high frequency of high concentra- tions of the elements indicated ........................ Artefacts .................................. Synopsis of regions where artefacts show relatively high frequencitl of the elements indicated ................................. Phosphorus in iron ............................. Coal in iron ............................... Alloying elements. Rust ........................... Summary .................................. Appendix: The microstructure after reduction of phosphorus-rich iron ore with charcoal at different temperatures. By Torsten Hansson and Sten Modin .......... Literature. ................................ -

Optical Properties of Common Rock-Forming Minerals

AppendixA __________ Optical Properties of Common Rock-Forming Minerals 325 Optical Properties of Common Rock-Forming Minerals J. B. Lyons, S. A. Morse, and R. E. Stoiber Distinguishing Characteristics Chemical XI. System and Indices Birefringence "Characteristically parallel, but Mineral Composition Best Cleavage Sign,2V and Relief and Color see Fig. 13-3. A. High Positive Relief Zircon ZrSiO. Tet. (+) 111=1.940 High biref. Small euhedral grains show (.055) parallel" extinction; may cause pleochroic haloes if enclosed in other minerals Sphene CaTiSiOs Mon. (110) (+) 30-50 13=1.895 High biref. Wedge-shaped grains; may (Titanite) to 1.935 (0.108-.135) show (110) cleavage or (100) Often or (221) parting; ZI\c=51 0; brownish in very high relief; r>v extreme. color CtJI\) 0) Gamet AsB2(SiO.la where Iso. High Grandite often Very pale pink commonest A = R2+ and B = RS + 1.7-1.9 weakly color; inclusions common. birefracting. Indices vary widely with composition. Crystals often euhedraL Uvarovite green, very rare. Staurolite H2FeAI.Si2O'2 Orth. (010) (+) 2V = 87 13=1.750 Low biref. Pleochroic colorless to golden (approximately) (.012) yellow; one good cleavage; twins cruciform or oblique; metamorphic. Olivine Series Mg2SiO. Orth. (+) 2V=85 13=1.651 High biref. Colorless (Fo) to yellow or pale to to (.035) brown (Fa); high relief. Fe2SiO. Orth. (-) 2V=47 13=1.865 High biref. Shagreen (mottled) surface; (.051) often cracked and altered to %II - serpentine. Poor (010) and (100) cleavages. Extinction par- ~ ~ alleL" l~4~ Tourmaline Na(Mg,Fe,Mn,Li,Alk Hex. (-) 111=1.636 Mod. biref. -

THE MELILITE (Gh50) SKARNS of ORAVIT¸A, BANAT, ROMANIA: TRANSITION to GEHLENITE (Gh85) and to VESUVIANITE

1255 The Canadian Mineralogist Vol. 41, pp. 1255-1270 (2003) THE MELILITE (Gh50) SKARNS OF ORAVIT¸A, BANAT, ROMANIA: TRANSITION TO GEHLENITE (Gh85) AND TO VESUVIANITE ILDIKO KATONA Laboratoire de Pétrologie, Modélisation des Matériaux et Processus, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, 4, Place Jussieu, F-75252 Paris, Cedex 05, France MARIE-LOLA PASCAL§ CNRS–ISTO (Institut des Sciences de la Terre d’Orléans), 1A, rue de la Férollerie, F-45071 Orléans, Cedex 02, France MICHEL FONTEILLES Laboratoire de Pétrologie, Modélisation des Matériaux et Processus, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, 4, Place Jussieu, F-75252 Paris, Cedex 05, France JEAN VERKAEREN Unité de Géologie, Université Catholique de Louvain-la-Neuve, Bâtiment Mercator, 3, Place Louis Pasteur, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium ABSTRACT Almost monomineralic Mg-rich gehlenite (~Gh50Ak46Na-mel4) skarns occur in a very restricted area along the contact of a diorite intrusion at Oravit¸a, Banat, in Romania, elsewhere characterized by more typical vesuvianite–garnet skarns. In the vein- like body of apparently unaltered gehlenite, the textural relations of the associated minerals (interstitial granditic garnet and, locally, monticellite, rare cases of exsolution of magnetite in the core zone of melilite grains) suggest that the original composi- tion of the gehlenite may have been different, richer in Si, Mg, Fe (and perhaps Na), in accordance with the fact that skarns are the only terrestrial type of occurrence of gehlenite-dominant melilite. The same minerals, monticellite and a granditic garnet, appear in the retrograde evolution of the Mg-rich gehlenite toward compositions richer in Al, the successive stages of which are clearly displayed, along with the final transformation to vesuvianite. -

The Crystal Structure of Synthetic Soda Melilite, Canaaisi207 1. Introduction

Zeitschrift fUr Kristallographie, Bd. 131, S. 314--321 (1970) The crystal structure of synthetic soda melilite, CaNaAISi207 By S. JOHN LOUISNATHAN Department of the Geophysical Sciences, The University of Chicago, Chicago (Received 25 August 1969) Auszug Die Kristallstruktur von synthetischem N atriummelilith wurde aus Dif- fraktometerdaten bis R = 5,10/0 verfeinert. Die Verbindung hat die gleiche Struktur wie die iibrigen, natiirlich vorkommenden Melilithe. Die Aluminium- und Siliciumatome sind in der Struktur geordnet, die Calcium- und Natrium- atome statistisch verteilt. Abstract The crystal structure of synthetic soda melilite was refined to R = 5.10/0 from three-dimensional diffractometer data. Soda melilite is isostructural with the other naturally-occuring melilites. Aluminum and Si atoms are ordered in the structure while Ca and N a atoms are disordered. 1. Introduction The literature on the melilite group of minerals with a discussion of the various proposed end-members was reviewed by CHRISTIE (1961 a and b; 1962). After prolonged discussion it is now generally accepted that CaNaAlSi207, called soda melilite, can be established as an end member, partly represented in some natural melilites. YODER (1964) showed that pure soda melilite is stable only at pressures in excess of 4 kbar. Its optical properties were determined by SCHAIRER, YODER and TILLEY (1965). The crystal-structure determination of soda melilite was under- taken as a part of a systematic structural study of the melilite group. The general composition of a melilite can be written as (Ca,Na)2 (Mg,Al)(Al,Si)207. Order-disorder of Mg,Al and Si among the tetra- hedral sites and diadochy of Ca, N a etc. -

Iron, Steel and Swords Script

Iron Ores General Remarks This planet consists of iron (32.1%), oxygen (30.1%), silicon (15.1%), magnesium (13.9%), sulfur (2.9%), nickel (1.8%), calcium (1.5%), and aluminium (1.4%); the remaining 1.2% are "trace amounts" of the 80 or so remaining elements. Most of that iron constitutes the core of the planet but we will not run out of iron compounds or iron ore found near to the surface for some time to come. Why is iron so prominent in this (and other) planet ? Because planets were formed from the stuff bred inside the first stars. The reaction chain for generating energy by nuclear fusion starts with hydrogen and stops after iron has been bred. Iron, if you like, is the ash eventually produced by fusing hydrogen to helium, helium and hydrogen to lithium, and so on. When those first stars "burnt out" after a few billon years, some of them coughed up their ashes in a mighty supernova explosion. In time, new stars were formed. Some of these are still burning and visible at night. One (our very own sund) is only visible during the day from a clumped-together iron-rich ash ball called earth. Advanced From the viewpoint of chemistry, iron (like copper) is a tricky element that can form many oxides, sulfides, carbonates, and so on. All these compounds could be used for smelting iron but some are better for that purpose than others. Sulfides are usually bad news. We know that from smelting copper and expect similar problems when smelting iron. -

The Iron-Ore Resources of Europe

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ALBERT B. FALL, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Bulletin 706 THE IRON-ORE RESOURCES OF EUROPE BY MAX ROESLER WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1921 CONTENTS. Page. Preface, by J. B. Umpleby................................................. 9 Introduction.............................................................. 11 Object and scope of report............................................. 11 Limitations of the work............................................... 11 Definitions.........................:................................. 12 Geology of iron-ore deposits............................................ 13 The utilization of iron ores............................................ 15 Acknowledgments...................................................... 16 Summary................................................................ 17 Geographic distribution of iron-ore deposits within the countries of new E urope............................................................. 17 Geologic distribution................................................... 22 Production and consumption.......................................... 25 Comparison of continents.............................................. 29 Spain..................................................................... 31 Distribution, character, and extent of the deposits....................... 31 Cantabrian Cordillera............................................. 31 The Pyrenees.................................................... -

The Iron Ores of Maryland, with an Account of the Iron Industry

Hass 77,>0 3- Book ffjZd6 MARYLAND GEOLOGICAL AND ECONOMIC SURVEY WM. BULLOCK CLARK, State Geologist REPORT ON THE IRON ORES OF MARYLAND WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE IRON INDUSTRY BY JOSEPH T. SINGEWALD, JR.- (Special Publication, Volume IX, Part III) THE JOHNS HOPKINS PRESS Baltimore, December, 1911 / / MARYLAND GEOLOGICAL AND ECONOMIC SURVEY WM. BULLOCK CLARK, State Geologist REPORT ON r? Sr THE IRON ORES OF MARYLAND / £ WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE IRON INDUSTRY BY JOSEPH T. SINGEWALD, JR. M (Special Publication, Volume IX, Part III) THE JOHNS HOPKINS PRESS • Baltimore, December, 1911 V n, ffi ft- sre so i CONTENTS PAGE PART III. REPORT ON THE IRON ORES OF MARYLAND, WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE IRON INDUSTRY. By Joseph T. Sxngewald, Jr. 121 The Ores of Iron.123 Magnetite . 124 Hematite . 124 Limonite . 124 Carbonate or Siderite. 125 Impurities in the Ores and Their Effects. 125 Mechanical Impurities. 125 Chemical Impurities. 126 Practical Considerations. 127 History of the Maryland Iron Industry. 128 The Colonial Period. 128 The Period from 1780 to 1830. 133 • The Period from 1830 to 1885. 133 The Period from 1885 to the present time. 136 Description of Maryland Iron Works.139 Maryland Furnaces. 139 Garrett County..'... 139 Allegany County. 139 Washington County. 143 Frederick County. 146 Carroll County. 149 Baltimore County. 150 Baltimore City. 159 Harford County. 160 Cecil County. 162 Howard County. 168 Anne Arundel County. 169 Prince George’s County. 171 Worcester County. 172 9 Other Iron Works in Maryland. 173 Allegany County. 173 Baltimore County. 173 Cecil County. 174 CONTENTS PAGE Queen Anne’s County. -

The Minerals of Tasmania

THE MINERALS OF TASMANIA. By W. F. Petterd, CM Z.S. To the geologist, the fascinating science of mineralogy must always be of the utmost importance, as it defines with remarkable exactitude the chemical constituents and com- binations of rock masses, and, thus interpreting their optical and physical characters assumed, it plays an important part part in the elucidation of the mysteries of the earth's crust. Moreover, in addition, the minerals of a country are invari- ably intimately associated with its industrial progress, in addition to being an important factor in its igneous and metamorphic geology. In this dual aspect this State affords a most prolific field, perhaps unequalled in the Common- wealth, for serious consideration. In this short article, I propose to review the subject of the mineralogy of this Island in an extremely concise manner, the object being, chiefly, to afford the members of the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science a cursory glimpse into Nature's hidden objects of wealth, beauty, and scientific interest. It will be readily understood that the restricted space at the disposal of the writer effectually prevents full justice being done to an absorbing subject, which is of almost universal interest, viewed from the one or the other aspect. The economic result of practical mining operations, as carried on in this State, has been of a most satisfactory character, and has, without doubt, added greatly to the national wealth ; but, for detailed information under this head, reference must be made to the voluminous statistical information, and the general progress, and other reports, issued by the Mines Department of the local Government. -

Sequence of Mineral Formation, Spinel-Perovskite-Spinel-Melilite, Does Not Agree with the Equilibrium Condensation Model (4)

MICRO-1JII-Y OF CALCIUM-ALUMINUM43GH INCLUSIONS FROM AL;LENDE. Ian D. Hutcheon, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637. Figh resolution scanning electron microscope (SEM) observations of separated phases from Ca-Al-rieh coarse-mined inclusions from Allende have revealed a fascinating wealth of micmn-&ze nrirreml gra2ns whose strmctures are not onkv eye-catching but uniquely infomtive as well. Such varied mineralogies as 0.4 pm perovskite hex+agons on spinel or 1 um spinel pyramids on hibonite as well as 0.1pm Fe grains inside vesicles in melilite and Ni-Fe particles in spinel raise questions concerning the fomtion of coarse- grained inclusions which existing models cannot answer. The texture of micron-size crystals and their pin-to-grain contacts generally argue for condensation, while the mineralogy of neighboring phases is often more con- asistent with liquid crystallization. We have examined five coarse-pained Allende.inclusions, using crystals hand-picked from the same mineral separates.used in oxygen isotope (1)and trace element (2) studies. Minerals were identified with.a solid state x-ray analyzer. The most striking feature we have observed is the ubiquitiaus presence of small perovskite crystals ranging in size from < 0.1 pm to 10 urn, epitaxially . grown on the exterior surfaces of euhedral spinel grains. Perovskite is most abundant in A1 1-16, a Type A inclusion (3) in which spinel is originally poikilitically enclosed by melilite. Numerous spinels survive the mineral separation wikh their original surfaces intact and it is these pristine external surfaces which are invariably covered by epitaxial pervoskite crystals. -

NASSAWANGO IRON FURNACE Ca1828-1850 NEAR SNOW HILL, MARYLAND

NASSAWANGO IRON FURNACE ca1828-1850 NEAR SNOW HILL, MARYLAND A NATIONAL HISTORIC MECHANICAL ENGINEERING LANDMARK OCTOBER 19, 1991 The American Society of Mechanical Engineers FURNACE DelMarVa Group TOWN Nassawango Iron Furnace HISTORY OF NASSAWANGO IRON FURNACE Bog iron was first discovered in the swamps produced over 700 tons of pig iron per year at along Nassawango Creek in the 1780’s and in Nassawango; Spence was also credited with 1828 the Maryland Iron Company was the installation of the hot-blast stove on top of incorporated to extract and process it. In the furnace. 1830, the Company constructed a furnace along the creek at a point roughly four miles Iron was produced at Nassawango until 1847 northwest of its confluence with the when lack of labor and poor market Pocomoke River near Snow Hill, MD. Shortly conditions caused Spence (who fell into thereafter, the Nassawango furnace began financial ruin) to shut down the furnace. The producing pig iron by the cold-blast process. property sat idle from that time forward and was used by successive owners mostly for In 1836, two of the Company’s creditors, the timber rights. In 1962, the heirs of Arthur Milby and Joseph Waples, foreclosed Georgia Smith Foster donated the property to on the property; that same year they sold it to the Worcester County Historical Society Benjamin Jones, a Philadelphia ironmonger. which undertook a systematic long range Jones, who owned other furnaces and had a program to stabilize the furnace and cut back formidable business that bought and sold the plant growth of the previous 100 years.