Inventory of Scottish Battlefields NGR Centred: NJ 562

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bruce, the Wallace and the Declaration of Arbroath. National, 2016, 23 Dec

Riach, A. (2016) The Bruce, The Wallace and the declaration of Arbroath. National, 2016, 23 Dec. This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/161524/ Deposited on: 30 April 2018 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk The Bruce, The Wallace and the Declaration of Arbroath The foundations of Scottish literature are the foundations of Scotland itself, in three epic poems and a letter. A fortnight ago (December 9), The National’s cover carried an image of Robert the Bruce’s face, the reconstruction from a cast of his skull. Yesterday a damp squib of unionist doggerel referred to Bruce and Wallace as no more than empty icons of hollow nationalism. Maybe it’s worth pausing to ask what they really mean. Alan Riach The battle of Bannockburn, 1314, the defining moment of victory for Bruce and the Scots and the turning point in the Wars of Independence, was in fact followed by many years of further warfare and even the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320 did not bring the threat of English domination to an end. John Barbour (c.1320-95) was born around the same year as the Declaration was written and his epic poem, The Bruce (1375), was composed only sixty years or so after the events. While Latin was the language of international politics, The Bruce was written in vernacular Scots for a local – including courtly – readership, drawing on stories Barbour had heard, some no doubt from eye-witnesses. -

01-Presidents Message (May-Jun 2020)

The Thistletire SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER 2020 Caledonian Club of Florida West, Inc. Your Board 2019-2020 BOARD: Dear Members: President Mary Ellen McMahon Vice President I hope this newsletter finds you all well and the COVID didn’t affect you. Frank Dr. Phil Miner and I are both staying close to home (I’m trying to stay out of mischief as well). Secretary This definitely has been a unique year and I know I will be very happy to say Barbara Shaffer “goodbye” to 2020. Treasurer Jean Walker I wish I could give you exciting news of upcoming socials but alas that is not to be, at least as of now. The Highland Fling originally planned for November DIRECTORS:• 2020 has been postponed to sometime in March or April of 2021. The Donald Campbell committee has not finalized a date yet with Palm Aire C.C. but when they do Rachel “Gay” Haines I will definitely let you all know so you can mark it on your calendar. Allan McIlraith We only had one summer 530 social which was in July at Stotlemyers. We Dr. Mary Thompson have decided that any other socials will be “virtual”. The BOD has been Margaret (Peg) Tonn trying to think of events that can be held via Zoom. If you have any ideas/ Linda Mercurio • suggestions we would LOVE to hear from you. SPECIAL CHAIRPERSONS From what I understand the Heritage Society is still planning the Highland Membership Games. Hopefully we can bid adieu to COVID and start planning some new Dr. Mary Thompson socials for 2021 (can you tell I love saying 2021?). -

Scotland's Status As a Nation

The Scotland-UN Committee SCOTLAND'S STATUS AS A NATION How Scotland Qualifies for the Right of Self-Determination James Wilkie The expression "people", as tentatively defined by the United Nations Organisation, denotes a social entity possessing a clear identity and its own characteristics as well as a lengthy common history, and it implies a relationship with a territory. These are the basic elements of a definition for the purpose of establishing whether such a social entity is a “people” fit to enjoy and exercise the right of self-determination. The Scottish qualifications are absolutely unchallengeable on all counts. This statement was originally prepared for use within the United Nations, the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe and other international organisations when the question of Scotland’s exercise of the right to self- determination was raised there. Scotland’s status as a nation is one of the key aspects to be considered by the national and international authorities, who are generally not very well informed on the subject, when the question arises of diplomatic recognition of an autonomous Scottish state. It is therefore written with a foreign readership in mind, and it emphasises the points that will make the Scottish case in international diplomatic circles. Scotland’s Case The basic ethnic component of the Scottish Nation is a fusion of three related Celtic peoples, with later minor infusions of Viking, Flemish and other Germanic blood, especially in the small south-eastern corner of the country. This composition has remained predominant right to the present day, because the demographic movement has overwhelmingly consisted of a movement of population from Scotland, the only major inward movement until very recent times having been extensive immigration by the closely related Celtic Irish. -

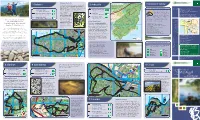

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-Àite Ann an Sgìre Prìomh Bhaile Na Gàidhealtachd

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Author: Roddy Maclean Photography: all images ©Roddy Maclean except cover photo ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot; p3 & p4 ©Somhairle MacDonald; p21 ©Calum Maclean. Maps: all maps reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/ except back cover and inside back cover © Ashworth Maps and Interpretation Ltd 2021. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2021. Design and Layout: Big Apple Graphics Ltd. Print: J Thomson Colour Printers Ltd. © Roddy Maclean 2021. All rights reserved Gu Aonghas Seumas Moireasdan, le gràdh is gean The place-names highlighted in this book can be viewed on an interactive online map - https://tinyurl.com/ybp6fjco Many thanks to Audrey and Tom Daines for creating it. This book is free but we encourage you to give a donation to the conservation charity Trees for Life towards the development of Gaelic interpretation at their new Dundreggan Rewilding Centre. Please visit the JustGiving page: www.justgiving.com/trees-for-life ISBN 978-1-78391-957-4 Published by NatureScot www.nature.scot Tel: 01738 444177 Cover photograph: The mouth of the River Ness – which [email protected] gives the city its name – as seen from the air. Beyond are www.nature.scot Muirtown Basin, Craig Phadrig and the lands of the Aird. Central Inverness from the air, looking towards the Beauly Firth. Above the Ness Islands, looking south down the Great Glen. -

The Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517

Cochran-Yu, David Kyle (2016) A keystone of contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7242/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] A Keystone of Contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517 David Kyle Cochran-Yu B.S M.Litt Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Ph.D. School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow September 2015 © David Kyle Cochran-Yu September 2015 2 Abstract The earldom of Ross was a dominant force in medieval Scotland. This was primarily due to its strategic importance as the northern gateway into the Hebrides to the west, and Caithness and Sutherland to the north. The power derived from the earldom’s strategic situation was enhanced by the status of its earls. From 1215 to 1372 the earldom was ruled by an uninterrupted MacTaggart comital dynasty which was able to capitalise on this longevity to establish itself as an indispensable authority in Scotland north of the Forth. -

Mid Argyll and Kintyre

Between the Lochs 1 Dalavich The forest that stretches between Loch Awe and 2 Ardcastle Information Centre Loch Avich is by turns dramatic, peaceful and inspirational. Three trails loop through it from the Take care on the hills Forestry Commission Scotland Barnaline car park located a mile north of Contact 1 Loch Avich Trail Ardcastle Point Trail West Argyll Forest District 5 miles/8 km - Allow 2½ hrs Dalavich. Pass through ancient Atlantic oakwood 5 miles/8 km - Allow 3 hrs Please remember that the weather Whitegates, Lochgilphead, Argyll PA31 8RS on the Dalavich on the hills can change very quickly. Tel: 01546 602518 Dalavich Oakwood Trail Oakwood trail or brave Crag Trail Even in summer, conditions on high 1 mile/1.6 km - Allow 45 min e-mail:[email protected] 2 miles/3.2 km - Allow 1 hr thundering waterfalls ground are often much colder and Web: www.forestry.gov.uk/scotland Avich Falls Trail and rapids on the Avich Hazel Burn Trail windier than at low levels, despite clear Public enquiry line 0845 FORESTS (367 3787) Falls trail. The Loch 2 miles/3.2 km - Allow 1 hr skies. If you are venturing off our waymarked trails 1¾ miles/2.8 km - Allow 45 min . For Fort onto the higher hills and mountains, here are some 3 William Discover a landscape carved from Avich trail crosses forest information Pitlochry Avich falls A9 pointers for a safe and enjoyable trip. A82 rock, cloaked with trees and that is home to red In the Living Forest on what’s Tobermory 4 available from MULL squirrels, red deer and . -

The Macarthur Surname

The MacArthur Surname Surname: MacArthur Branch: MacArthur Origins: Scottish Country: Scotland Scottish Flag Arms of Scotland Background: In Gaelic, MacArthur means Son of Arthur. The Clan MacArthur is one of the oldest of Argyll and its age is referred to in the proverb, "There is nothing older, unless the hills, MacArthur and the devil". The MacArthurs themselves claim descent from Arthur, that early resistance fighter who may have fought against the expansionist English for the Scots. The MacArthurs supported Bruce and were rewarded with grants of extensive lands in Argyll including those of the MacDougalls and the chief was appointed Captain of the Castle of Dunstaffnage. This was indeed the peak of their fortunes for when James I returned from exile in England, in his launch to regain power he executed Iain MacArthur chief of the clan from which the clan never recovered. From thereafter it was the name of Campbell rather than MacArthur that flourished in the region. Heraldry Motto: Fide Et Opera, Faith and Work. Battle Cry: Olso O' Elso, Listen O'listen. Arms: Azure, a maltese cross Argent, between three antique crowns. Crest: Two laurel branches in orle proper. Badge: Two laurel branches in orle, proper. Plant: Fir club moss, wild myrtle. History of the MacArthur Surname he MacArthur’s are Celts, and the family of Arthur is one of the oldest clans in Argyll, so ancient that even in remote Celtic times there was a Gaelic couplet which is freely translated, ‘the hills and streams and Mac-alpine but whence came forth MacArthur?’ The MacArthur’s supported Robert the Bruce in the struggle for the independence of Scotland, and their leader, Mac ic Artair, was rewarded with lands in mid Argyll, which had belonged to those who had opposed the king. -

Loch Awe (Potentially Vulnerable Area 01/34)

Loch Awe (Potentially Vulnerable Area 01/34) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Highland and Argyll Argyll and Bute Council Etive coastal Summary of flooding impacts Summary of flooding impactsSummary At risk of flooding • 20 residential properties • 30 non-residential properties • £100,000 Annual Average Damages (damages by flood source shown left) Summary of objectives to manage flooding Objectives have been set by SEPA and agreed with flood risk management authorities. These are the aims for managing local flood risk. The objectives have been grouped in three main ways: by reducing risk, avoiding increasing risk or accepting risk by maintaining current levels of management. Objectives Many organisations, such as Scottish Water and energy companies, actively maintain and manage their own assets including their risk from flooding. Where known, these actions are described here. Scottish Natural Heritage and Historic Environment Scotland work with site owners to manage flooding where appropriate at designated environmental and/or cultural heritage sites. These actions are not detailed further in the Flood Risk Management Strategies. Summary of actions to manage flooding The actions below have been selected to manage flood risk. Flood Natural flood New flood Community Property level Site protection protection management warning flood action protection plans scheme/works works groups scheme Actions Flood Natural flood Maintain flood Awareness Surface water Emergency protection management warning raising plan/study plans/response study study Maintain flood Strategic Flood Planning Self help Maintenance protection mapping and forecasting policies scheme modelling 357 Section 2 Highland and Argyll Local Plan District Loch Awe (Potentially Vulnerable Area 01/34) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Highland and Argyll Argyll and Bute Council River Awe Background This Potentially Vulnerable Area is The main rivers are the Awe and the located around Loch Awe and includes Orchy. -

Declaration of Arbroath Sealants' Information Sheets

Alexander Fraser Alexander Fraser was born into the Touch-Fraser line of the family but his exact date of birth is unknown. In autumn 1307, Alexander Fraser swore fealty to Robert the Bruce and accompanied the king on military campaigns in 1307-08. He fought at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. He may have been knighted before the Battle of Bannockburn and the title seems to have first been used in 1315, when Robert Bruce gave lands to his ‘beloved and faithful’ Alexander Fraser, knight. In about 1316 Alexander Fraser married Mary Bruce, sister of Robert the Bruce. He had become chamberlain of Scotland, the title being used in a charter dated 10 December 1319. He held this position until at least 5 March 1327. At the parliament of 1320, he attached his seal to the Declaration of Arbroath. His other titles included sheriff of Kincardine and sheriff of Stirling, and he held extensive lands north of the Firth of Forth. Alexander Fraser’s extensive estates and alliance to the royal family must have made him an influential figure. He fought and died at the Battle of Dupplin on 10-11 August 1332. Definitions: Fealty = promise to be loyal Chamberlain = manager of a royal household Charter = a legal document that sets out rights or obligations Image: Mike Brooks © Queen’s Printer for Scotland, NRS, SP13/7 January 2021 William Oliphant Sir William Oliphant of Dupplin and Aberdalgie, attached his seal to the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320. The earliest reference to him is in a list of prisoners captured at the Battle of Dunbar in 1296. -

The Clan Gillean

Ga-t, $. Mac % r /.'CTJ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://archive.org/details/clangilleanwithpOOsinc THE CLAN GILLEAN. From a Photograph by Maull & Fox, a Piccadilly, London. Colonel Sir PITZROY DONALD MACLEAN, Bart, CB. Chief of the Clan. v- THE CLAN GILLEAN BY THE REV. A. MACLEAN SINCLAIR (Ehartottftcton HASZARD AND MOORE 1899 PREFACE. I have to thank Colonel Sir Fitzroy Donald Maclean, Baronet, C. B., Chief of the Clan Gillean, for copies of a large number of useful documents ; Mr. H. A. C. Maclean, London, for copies of valuable papers in the Coll Charter Chest ; and Mr. C. R. Morison, Aintuim, Mr. C. A. McVean, Kilfinichen, Mr. John Johnson, Coll, Mr. James Maclean, Greenock, and others, for collecting- and sending me genea- logical facts. I have also to thank a number of ladies and gentlemen for information about the families to which they themselves belong. I am under special obligations to Professor Magnus Maclean, Glasgow, and Mr. Peter Mac- lean, Secretary of the Maclean Association, for sending me such extracts as I needed from works to which I had no access in this country. It is only fair to state that of all the help I received the most valuable was from them. I am greatly indebted to Mr. John Maclean, Convener of the Finance Committee of the Maclean Association, for labouring faithfully to obtain information for me, and especially for his efforts to get the subscriptions needed to have the book pub- lished. I feel very much obliged to Mr. -

Knapdale Coastal Catchment Summary

Published October 2010 Argyll and Lochaber area management plan catchment summaries Knapdale coastal catchment summary Introduction Knapdale coastal catchment covers 673 km2 and includes all the freshwater on the west side of Knapdale Peninsula from Tarbert in the south to Oban and the mouth of Loch Etive in the north as shown by the grey shading in Map 1. The catchment contains: 24 water bodies, four of which are heavily modified water bodies (HMWBs) and one is artificial; is adjacent to 15 coastal water bodies; contains/is adjacent to 16 protected areas. The main land-uses and water uses associated with catchment are forestry, agriculture and hydropower generation. Map 1: Area covered by Knapdale coastal catchment shown in grey Published October 2010 Further information on Knapdale coastal catchment can be found on the river basin planning interactive map – www.sepa.org.uk/water/river_basin_planning.aspx Classification summary Ecological No. WB ID Name WB category status (ES) WBs or potential (EP) High ES 2 10257 Allt Cinn-locha/Easan Tom River Luirg 10293 Abhainn na Cille River Good ES 18 10269 Barbreck River River 10299 Feochan Bheag River 10302 Feochan Mhor/River Nell (d/s River Loch Nell) 10303 Feochan Mhor/River Nell (u/s River Loch Nell) 200035 Loch na Cille Coastal 200052 Loch Craignish Coastal 200056 Loch Melfort Coastal 200058 Sound of Shuna Coastal 200062 Loch Feochan Coastal 200306 Loch Caolisport Coastal 200307 West Loch Tarbert (Kintyre) Coastal 200318 Sound of Jura Coastal 200321 Loch Crinan Coastal 200336 Loch Sween Coastal -

Rambles Through Craignish

Rambles through Craignish Robert A Campbell 11/6/1947 Original 111 page document typewritten by the Author (Robert A Campbell) in 1947; transcribed into digital form by Bob & Anne Carss in 2019. Original unbound pages held by Clive Brown, having been given to him by George McKinlay during the 1990’s; George lived at Corranbeg until the late 1980’s, but how he acquired the document is not known. Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 4 How to get to Craignish. .................................................................................................... 5 Best time to Visit. ............................................................................................................... 6 Books to Read. .................................................................................................................. 6 Proposed Itinerary. ............................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1 .............................................................................................................................. 9 The Estate of the Campbells of Craignish. ......................................................................... 9 The Estate of the Campbells of Craignish. ................................................................... 10 Sale of the Estate ...........................................................................................................