Fall 1991 Wind Bell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

PUBLICATION of SAN FRANCISCO ZEN CENTER Vol. XXXVI No. 1 Spring I Summer 2002 CONTENTS

PUBLICATION OF SAN FRANCISCO ZEN CENTER Vol. XXXVI No. 1 Spring I Summer 2002 CONTENTS TALKS 3 The Gift of Zazen BY Shunryu Suzuki-roshi 16 Practice On and Off the Cushion BY Anna Thom 20 The World Is Vast and Wide BY Gretel Ehrlich 36 An Appropriate Response BY Abbess Linda Ruth Cutts POETRY AND ART 4 Kannon in Waves BY Dan Welch (See also front cover and pages 9 and 46) 5 Like Water BY Sojun Mel Weitsman 24 Study Hall BY Zenshin Philip Whalen NEWS AND FEATURES 8 orman Fischer Revisited AN INTERVIEW 11 An Interview with Annie Somerville, Executive Chef of Greens 25 Projections on an Empty Screen BY Michael Wenger 27 Sangha-e! 28 Through a Glass, Darkly BY Alan Senauke 42 'Treasurer's Report on Fiscal Year 2002 DY Kokai Roberts 2 covet WNO eru 111 -ASSl\ll\tll.,,. o..N WEICH The Gi~ of Zazen Shunryu Suzuki Roshi December 14, 1967-Los Altos, California JAM STILL STUDYING to find out what our way is. Recently I reached the conclusion that there is no Buddhism or Zen or anythjng. When I was preparing for the evening lecture in San Francisco yesterday, I tried to find something to talk about, but I couldn't; then I thought of the story 1 was told in Obun Festival when I was young. The story is about water and the people in Hell Although they have water, the people in hell cannot drink it because the water burns like fire or it looks like blood, so they cannot drink it. -

Hakuin on Kensho: the Four Ways of Knowing/Edited with Commentary by Albert Low.—1St Ed

ABOUT THE BOOK Kensho is the Zen experience of waking up to one’s own true nature—of understanding oneself to be not different from the Buddha-nature that pervades all existence. The Japanese Zen Master Hakuin (1689–1769) considered the experience to be essential. In his autobiography he says: “Anyone who would call himself a member of the Zen family must first achieve kensho- realization of the Buddha’s way. If a person who has not achieved kensho says he is a follower of Zen, he is an outrageous fraud. A swindler pure and simple.” Hakuin’s short text on kensho, “Four Ways of Knowing of an Awakened Person,” is a little-known Zen classic. The “four ways” he describes include the way of knowing of the Great Perfect Mirror, the way of knowing equality, the way of knowing by differentiation, and the way of the perfection of action. Rather than simply being methods for “checking” for enlightenment in oneself, these ways ultimately exemplify Zen practice. Albert Low has provided careful, line-by-line commentary for the text that illuminates its profound wisdom and makes it an inspiration for deeper spiritual practice. ALBERT LOW holds degrees in philosophy and psychology, and was for many years a management consultant, lecturing widely on organizational dynamics. He studied Zen under Roshi Philip Kapleau, author of The Three Pillars of Zen, receiving transmission as a teacher in 1986. He is currently director and guiding teacher of the Montreal Zen Centre. He is the author of several books, including Zen and Creative Management and The Iron Cow of Zen. -

New American Zen: Examining American Women's Adaptation of Traditional Japanese Soto Zen Practice Courtney M

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 2011 New American Zen: Examining American Women's Adaptation of Traditional Japanese Soto Zen Practice Courtney M. Just Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI11120903 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Just, Courtney M., "New American Zen: Examining American Women's Adaptation of Traditional Japanese Soto Zen Practice" (2011). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 527. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/527 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida NEW AMERICAN ZEN: EXAMINING AMERICAN WOMEN’S ADAPTATION OF TRADITIONAL JAPANESE SOTO ZEN PRACTICE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in LIBERAL STUDIES by Courtney Just 2011 To: Dean Kenneth Furton College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by Courtney Just, and entitled New American Zen: Examining American Women’s Adaptation of Traditional Japanese Soto Zen Practice, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Laurie Shrage ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Kiriake Xerohemona ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Lesley A. Northup, Major Professor Date of Defense: November 10, 2011 The thesis of Courtney Just is approved. –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Dean Kenneth Furton College of Arts and Science ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Dean Lakshmi N. -

A Short Talk During Zazen

A Short Talk During Zazen Shunryu Suzuki Roshi (Presented during zazen on the moming of June 28, 1970, between the tenth and eleventh Sandokai lectures) YouSHOULD SIT WITH YOUR WHOLE BODY: your spine, mouth, toes, mudra. l Check on your posture during zazen. Each part of your body should practice zazen independently or separately: Your toes should prac tice zazen independently, your mudra should practice zazen independently, and your spine and your mouth should practice zazen independently. You should feel each part of your body doing zazen independently. Each part of your body should participate completely in zazen. Check to see that each part of your body is doing zazen independently- this is also known as shiknntaza. To think, "I am doing zazen" or "my body is doing zazen" is wrong understanding. It is a self-centered idea. The mudra is especially important. You should not feel as if you are resting your mudra on the heel of your foot for your own convenience. Your mudra should be placed in its own position. Don't move your legs for your own convenience. Your legs are practic ing their own zazen independently and are com pletely involved in their own pain. They are doing zazen through pain. You should all ow them to practice their own zazen. If you think you are practicing zazen, you are involved in some selfish, egotistical idea. If you think that you have a difficulty in some part of your body, then the rest of the body should help the part that is in difficulty. You are not having difficulty with some part of your body, but the part of the body is having difficulty: for example, your mudra is having difficulty. -

A Beginner's Guide to Meditation

ABOUT THE BOOK As countless meditators have learned firsthand, meditation practice can positively transform the way we see and experience our lives. This practical, accessible guide to the fundamentals of Buddhist meditation introduces you to the practice, explains how it is approached in the main schools of Buddhism, and offers advice and inspiration from Buddhism’s most renowned and effective meditation teachers, including Pema Chödrön, Thich Nhat Hanh, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, Sharon Salzberg, Norman Fischer, Ajahn Chah, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, Sylvia Boorstein, Noah Levine, Judy Lief, and many others. Topics include how to build excitement and energy to start a meditation routine and keep it going, setting up a meditation space, working with and through boredom, what to look for when seeking others to meditate with, how to know when it’s time to try doing a formal meditation retreat, how to bring the practice “off the cushion” with walking meditation and other practices, and much more. ROD MEADE SPERRY is an editor and writer for the Shambhala Sun magazine. Sign up to receive news and special offers from Shambhala Publications. Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala. A BEGINNER’S GUIDE TO Meditation Practical Advice and Inspiration from Contemporary Buddhist Teachers Edited by Rod Meade Sperry and the Editors of the Shambhala Sun SHAMBHALA Boston & London 2014 Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com © 2014 by Shambhala Sun Cover art: André Slob Cover design: Liza Matthews All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Introduction Shunryu Suzuki Sojun Mel Weitsman

Introduction Shunryu Suzuki Sojun Mel Weitsman INTHE SUMMER OF 1970 Suzuki Roshi gave these talks on the Sandokai of Sekito Kisen. BRANCHING Suzuki Roshi had come to America in 1959, leaving Rinso-in, his tem STREAMS ple in Yaizu, Japan, to serve as FLOW IN THE priest for the Japanese-American congregation at Sokoji temple at DARKNESS 1881 Bush Street in San Francisco. During those years a large number of people came to practice with him, and San Francisco Zen Center Zen Talks on the Sandokai was born. Suzuki Roshi became By tht author of Z~n Mind. Beginne~s Mind surrounded by so many enthusias- tic American Zen students that in 1969 he and his students moved to a large building at 300 Page Street and established Beginner's Mind Temple. Two years earlier, Zen Center had acquired the Tassajara resort and hot springs, which is at the end of a four teen-mile dirt road that winds through the rugged mountains of the Los Padres National Forest near the central coast of California. He and his stu dents created the first Zen Buddhist monastery in America, Zenshinji (Zen Mind/Heart Te mple). We were starting from scratch under Suzuki Roshi's guidance. Each year Tassajara Zen Mountain Center has two intensive practice period retreats: October through December, and January through March. These two practice periods include many hours of zazen (cross-legged seated meditation) each day, lectures, study, and physical work. The students are there for the entire time. In the spring and summer months (May through August), Tassajara provides a guest season for people who are attracted by the hot mineral baths and the quiet atmosphere. -

Program Guide

IBFF NO1 NOVEMBER 20–23, 2003 LOS ANGELES WWW.IBFF.ORG INTERNATIONAL BUDDHIST FILM FESTIVAL Debra Bloomfield Jerry Burchard John Paul Caponigro Simon Chaput Mark Citret Linda Connor Lynn Davis Peter deLory Don Farber Richard Gere Susannah Hays Jim Henkel Lena Herzog Kenro Izu REFLECTING BUDDHA: Michael Kenna IMAGES BY Heather Kessinger Hirokazu Kosaka CONTEMPORARY Alan Kozlowski PHOTOGRAPHERS Wayne Levin Stu Levy NOVEMBER 14–23 David Liittschwager Elaine Ling Exhibition and Sale to Benefit the International Buddhist Film Festival John Daido Loori Book Signings by Participating Photographers Yasuaki Matsumoto Throughout the Exhibition Steve McCurry Curated by Linda Connor Pasadena Museum of California Art Susan Middleton 490 East Union Street, Pasadena, California Charles Reilly Third Floor Exhibition Space Open Wed. to Sun. 10 am to 5 pm, Fri. to 8 pm David Samuel Robbins www.pmcaonline.org 626.568.3665 Stuart Rome Meridel Rubenstein Larry Snider 2003 pigment print © Linda Connor, Ladakh, India digital archival Nubra Valley, Camille Solyagua John Willis The Dalai Lama’s Rainbow The Dalai Lama’s NOV 20–23 at LACMA www.ibff.org Alison Wright image: Welcome to the first International Buddhist Film Festival. The Buddhist understanding that what we experience is projection, is cinema in the most profound sense. In the sixth century BC, Prince Siddhartha, the future Buddha, was challenged by personal and political upheaval, and he heroically strove to find a meaningful way of living. Waking up and paying attention, he discovered a path of spiritual transformation. The seeds of this breakthrough have continued to flower through 2,500 years. A new wave of contemporary cinema is emerging to embrace all the strands of Buddhism—directly, obliquely, reverently, critically, and comedically too. -

Soto Zen: an Introduction to Zazen

SOT¯ O¯ ZEN An Introduction to Zazen SOT¯ O¯ ZEN: An Introduction to Zazen Edited by: S¯ot¯o Zen Buddhism International Center Published by: SOTOSHU SHUMUCHO 2-5-2, Shiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-8544, Japan Tel: +81-3-3454-5411 Fax: +81-3-3454-5423 URL: http://global.sotozen-net.or.jp/ First printing: 2002 NinthFifteenth printing: printing: 20122017 © 2002 by SOTOSHU SHUMUCHO. All rights reserved. Printed in Japan Contents Part I. Practice of Zazen....................................................7 1. A Path of Just Sitting: Zazen as the Practice of the Bodhisattva Way 9 2. How to Do Zazen 25 3. Manners in the Zend¯o 36 Part II. An Introduction to S¯ot¯o Zen .............................47 1. History and Teachings of S¯ot¯o Zen 49 2. Texts on Zazen 69 Fukan Zazengi 69 Sh¯ob¯ogenz¯o Bend¯owa 72 Sh¯ob¯ogenz¯o Zuimonki 81 Zazen Y¯ojinki 87 J¯uniji-h¯ogo 93 Appendixes.......................................................................99 Takkesa ge (Robe Verse) 101 Kaiky¯o ge (Sutra-Opening Verse) 101 Shigu seigan mon (Four Vows) 101 Hannya shingy¯o (Heart Sutra) 101 Fuek¯o (Universal Transference of Merit) 102 Part I Practice of Zazen A Path of Just Sitting: Zazen as the 1 Practice of the Bodhisattva Way Shohaku Okumura A Personal Reflection on Zazen Practice in Modern Times Problems we are facing The 20th century was scarred by two World Wars, a Cold War between powerful nations, and countless regional conflicts of great violence. Millions were killed, and millions more displaced from their homes. All the developed nations were involved in these wars and conflicts. -

BEYOND THINKING a Guide to Zen Meditation

ABOUT THE BOOK Spiritual practice is not some kind of striving to produce enlightenment, but an expression of the enlightenment already inherent in all things: Such is the Zen teaching of Dogen Zenji (1200–1253) whose profound writings have been studied and revered for more than seven hundred years, influencing practitioners far beyond his native Japan and the Soto school he is credited with founding. In focusing on Dogen’s most practical words of instruction and encouragement for Zen students, this new collection highlights the timelessness of his teaching and shows it to be as applicable to anyone today as it was in the great teacher’s own time. Selections include Dogen’s famous meditation instructions; his advice on the practice of zazen, or sitting meditation; guidelines for community life; and some of his most inspirational talks. Also included are a bibliography and an extensive glossary. DOGEN (1200–1253) is known as the founder of the Japanese Soto Zen sect. Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications. Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala. Translators Reb Anderson Edward Brown Norman Fischer Blanche Hartman Taigen Dan Leighton Alan Senauke Kazuaki Tanahashi Katherine Thanas Mel Weitsman Dan Welch Michael Wenger Contributing Translator Philip Whalen BEYOND THINKING A Guide to Zen Meditation Zen Master Dogen Edited by Kazuaki Tanahashi Introduction by Norman Fischer SHAMBHALA Boston & London 2012 SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue -

Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha Continued from Previous Page It Was Needed, Each One Doing a Little Bit More Voices to Bring the Garden to Life

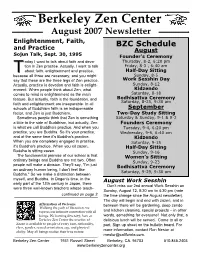

Berkeley Zen Center August 2007 Newsletter Enlightenment, Faith, BZC Schedule and Practice August Sojun Talk, Sept. 30, 1995 Founder’s Ceremony oday I want to talk about faith and devo- Thursday, 8-2, 6:20 pm tion in Zen practice. Actually, I want to talk Friday, 8-3 , 6:40 am TTabout faith, enlightenment and practice, Half-Day Sitting because all three are necessary, and you might Sunday, 8-5 say that these are the three legs of Zen practice. Work Sesshin Day Actually, practice is devotion and faith is enlight- Sunday, 8-12 enment. When people think about Zen, what Kidzendo comes to mind is enlightenment as the main Saturday, 8-18 feature. But actually, faith is the foundation, and Bodhisattva Ceremony Saturday, 8-25, 9:30 am faith and enlightenment are inseparable. In all schools of Buddhism faith is an indispensable September factor, and Zen is just Buddhism. Two-Day Study Sitting Sometimes people think that Zen is something Saturday & Sunday, 9-1 & 9-2 a little to the side of Buddhism, but actually, Zen Founders Ceremony is what we call Buddha's practice. And when you Tuesday, 9-4, 6:20 pm practice, you are Buddha. So it's your practice, Wednesday, 9-5, 6:40 am and at the same time it's Buddha's practice. Kidzendo When you are completely engaged in practice, Saturday, 9-15 it's Buddha's practice. When you sit zazen, Half-Day Sitting Buddha is sitting zazen. Sunday, 9-16 The fundamental premise of our school is that Women’s Sitting ordinary beings and Buddha are not two. -

Commentary by Shodo Harada

Commentary by Shodo Harada For the week we are here together, I would like to talk about the Ten Oxherding Pictures. This text, which dates from the twelfth century, is one of the oldest documents of Zen history. The Blue Cliff Record, another of the most famous, historically recorded Zen texts, was written by Engo Kokugon in the years of his lifetime, from 1063 to 1135. His brother disciple, Daizui Genjo, had a disciple named Kakuan Shion. Kakuan Shion wrote the text for the Ten Oxherding Pictures, and then Kakuan Shion’s grandson disciple, Gion, added the pictures. Compared to the Blue Cliff Record, this was a very accessible text. The pictures could be seen, and the short pieces of poetry could be heard and remembered. Because of this, Kakuan’s work was able to reach many, many people. This is story of the taming of an ox, of how a wild ox is caught and tamed. The catching and taming of the wild ox are likened to a person’s process in practice. Why an ox? Why is the story that of the taming of an ox? In India, oxen were considered very precious and were carefully taken care of. Because India was a Hindu country, cows were considered messengers of God, and everywhere oxen and cows walked freely, mingling with humans as equals. So to raise an ox meant to work on your divine self. In the Buddhist sutras there is also a teaching about how we have to grab the ox’s snout and not let him rough up the neighbor’s garden–in that way to always keep a firm grip on the nose of this ox.