Revolution, Evolution, Or Devolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nationalism in the French Revolution of 1789

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2014 Nationalism in the French Revolution of 1789 Kiley Bickford University of Maine - Main Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Cultural History Commons Recommended Citation Bickford, Kiley, "Nationalism in the French Revolution of 1789" (2014). Honors College. 147. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/147 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATIONALISM IN THE FRENCH REVOLUTION OF 1789 by Kiley Bickford A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for a Degree with Honors (History) The Honors College University of Maine May 2014 Advisory Committee: Richard Blanke, Professor of History Alexander Grab, Adelaide & Alan Bird Professor of History Angela Haas, Visiting Assistant Professor of History Raymond Pelletier, Associate Professor of French, Emeritus Chris Mares, Director of the Intensive English Institute, Honors College Copyright 2014 by Kiley Bickford All rights reserved. Abstract The French Revolution of 1789 was instrumental in the emergence and growth of modern nationalism, the idea that a state should represent, and serve the interests of, a people, or "nation," that shares a common culture and history and feels as one. But national ideas, often with their source in the otherwise cosmopolitan world of the Enlightenment, were also an important cause of the Revolution itself. The rhetoric and documents of the Revolution demonstrate the importance of national ideas. -

The Fundamental Determinants of Anti-Authoritarianism

The Fundamental Determinants of Anti-Authoritarianism Davide Cantoni David Y. Yang Noam Yuchtman Y. Jane Zhang* March 2017 Abstract Which fundamental factors are associated with individuals holding democratic, anti-authori- tarian ideologies? We conduct a survey eliciting Hong Kong university students’ political atti- tudes and behavior in an ongoing pro-democracy movement. We construct indices measuring students’ anti-authoritarianism, and link these to a comprehensive profile of fundamental eco- nomic preferences; personalities; cognitive abilities; and family backgrounds. We find that fundamental economic preferences, particularly risk tolerance and pro-social preferences, are the strongest predictors of anti-authoritarian ideology and behavior. We also study simulta- neously determined outcomes, arguably both cause and consequence of ideology. Examining these, we find that anti-authoritarians are more pessimistic about Hong Kong’s political out- look and about their fellow students’ support for the movement; their social networks are more political; they consume different media; and, they are more politically informed than other students. Our extraordinarily rich data suggest that individuals’ deep preferences should be considered alongside payoffs and beliefs in explaining political behavior. Keywords: Political movements, ideology, preferences *Cantoni: University of Munich, CEPR, and CESifo. Email: [email protected]. Yang: Stanford University. Email: [email protected]. Yuchtman: UC-Berkeley, Haas School of Business, NBER, and CESifo. Email: [email protected]. Zhang: Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Email: [email protected]. Helpful and much appreciated suggestions, critiques and encouragement were provided by Doug Bernheim, Arun Chandrasekhar, Ernesto Dal Bo,´ Matthew Gentzkow, Peter Lorentzen, Muriel Niederle, Torsten Persson, and many seminar and conference participants. -

How Revolutionary Was the American Revolution? The

How Revolutionary Was The American Revolution? The American Revolution was a political revolution that separated England’s North American colonies from Great Britain and led to the formation of the United States of America. The Revolution was achieved in large part by the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), which was fought between England against America and its allies (France, Spain, and the Dutch Republic). The American Revolution embodied and reflected the principles of the Enlightenment, which emphasized personal liberty and freedom from tyranny among other ideals. The American revolutionaries and the Founding Fathers of the United States sought to create a nation without the shackles of the rigid social hierarchy that existed in Europe. Although the American Revolution succeeded in establishing a new nation that was built on the principles of personal freedom and democracy, scholars today continue to debate whether or not the American Revolution was truly all that revolutionary. Social and Ideological Effects of the American Revolution On the one hand, the American Revolution was not a complete social revolution such as the French Revolution in 1789 or the Russian Revolution in 1917. The American Revolution did not produce a total upheaval of the previously existing social and institutional structures. It also did not replace the old powers of authority with a new social group or class. On the other hand, for most American colonists fighting for independence, the American Revolution represented fundamental social change in addition to political change. The ideological backdrop for the Revolution was based on the concept of replacing older forms of feudal-type relationships with a social structure based on republicanism and democracy. -

Download Download

Ajalooline Ajakiri, 2016, 3/4 (157/158), 477–511 Historical consciousness, personal life experiences and the orientation of Estonian foreign policy toward the West, 1988–1991 Kaarel Piirimäe and Pertti Grönholm ABSTRACT The years 1988 to 1991 were a critical juncture in the history of Estonia. Crucial steps were taken during this time to assure that Estonian foreign policy would not be directed toward the East but primarily toward the integration with the West. In times of uncertainty and institutional flux, strong individuals with ideational power matter the most. This article examines the influence of For- eign Minister Lennart Meri’s and Prime Minister Edgar Savisaar’s experienc- es and historical consciousness on their visions of Estonia’s future position in international affairs. Life stories help understand differences in their horizons of expectation, and their choices in conducting Estonian diplomacy. Keywords: historical imagination, critical junctures, foreign policy analysis, So- viet Union, Baltic states, Lennart Meri Much has been written about the Baltic states’ success in breaking away from Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and their decisive “return to the West”1 via radical economic, social and politi- Research for this article was supported by the “Reimagining Futures in the European North at the End of the Cold War” project which was financed by the Academy of Finland. Funding was also obtained from the “Estonia, the Baltic states and the Collapse of the Soviet Union: New Perspectives on the End of the Cold War” project, financed by the Estonian Research Council, and the “Myths, Cultural Tools and Functions – Historical Narratives in Constructing and Consolidating National Identity in 20th and 21st Century Estonia” project, which was financed by the Turku Institute for Advanced Studies (TIAS, University of Turku). -

Preoccupied by the Past

© Scandia 2010 http://www.tidskriftenscandia.se/ Preoccupied by the Past The Case of Estonian’s Museum of Occupations Stuart Burch & Ulf Zander The nation is born out of the resistance, ideally without external aid, of its nascent citizens against oppression […] An effective founding struggle should contain memorable massacres, atrocities, assassina- tions and the like, which serve to unite and strengthen resistance and render the resulting victory the more justified and the more fulfilling. They also can provide a focus for a ”remember the x atrocity” histori- cal narrative.1 That a ”foundation struggle mythology” can form a compelling element of national identity is eminently illustrated by the case of Estonia. Its path to independence in 98 followed by German and Soviet occupation in the Second World War and subsequent incorporation into the Soviet Union is officially presented as a period of continuous struggle, culminating in the resumption of autonomy in 99. A key institution for narrating Estonia’s particular ”foundation struggle mythology” is the Museum of Occupations – the subject of our article – which opened in Tallinn in 2003. It conforms to an observation made by Rhiannon Mason concerning the nature of national museums. These entities, she argues, play an important role in articulating, challenging and responding to public perceptions of a nation’s histories, identities, cultures and politics. At the same time, national museums are themselves shaped by the nations within which they are located.2 The privileged role of the museum plus the potency of a ”foundation struggle mythology” accounts for the rise of museums of occupation in Estonia and other Eastern European states since 989. -

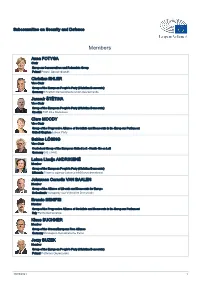

List of Members

Subcommittee on Security and Defence Members Anna FOTYGA Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Christian EHLER Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Jaromír ŠTĚTINA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Czechia TOP 09 a Starostové Clare MOODY Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament United Kingdom Labour Party Sabine LÖSING Vice-Chair Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Germany DIE LINKE. Laima Liucija ANDRIKIENĖ Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Lithuania Tėvynės sąjunga-Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai Johannes Cornelis VAN BAALEN Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Netherlands Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie Brando BENIFEI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Klaus BUCHNER Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei Jerzy BUZEK Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska 30/09/2021 1 Aymeric CHAUPRADE Member Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group France Les Français Libres Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party -

The Revolution of 1848 in the History of French Republicanism Samuel Hayat

The Revolution of 1848 in the History of French Republicanism Samuel Hayat To cite this version: Samuel Hayat. The Revolution of 1848 in the History of French Republicanism. History of Political Thought, Imprint Academic, 2015, 36 (2), pp.331-353. halshs-02068260 HAL Id: halshs-02068260 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02068260 Submitted on 14 Mar 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. History of Political Thought, vol. 36, n° 2, p. 331-353 PREPRINT. FINAL VERSION AVAILABLE ONLINE https://www.ingentaconnect.com/contentone/imp/hpt/2015/00000036/00000002/art00006 The Revolution of 1848 in the History of French Republicanism Samuel Hayat Abstract: The revolution of February 1848 was a major landmark in the history of republicanism in France. During the July monarchy, republicans were in favour of both universal suffrage and direct popular participation. But during the first months of the new republican regime, these principles collided, putting republicans to the test, bringing forth two conceptions of republicanism – moderate and democratic-social. After the failure of the June insurrection, the former prevailed. During the drafting of the Constitution, moderate republicanism was defined in opposition to socialism and unchecked popular participation. -

Euromaidan Values from a Comparative Perspective

Social, Health, and Communication Studies Journal Contemporary Ukraine: A case of Euromaidan, Vol. 1(1), November 2014 MacEwan University, Canada National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, Ukraine Ternopil State Medical University, Ukraine Article Euromaidan Values from a Comparative Perspective Sviatoslav Sviatnenko, graduate student, Maastricht University, Netherlands Dr. Alexander Vinogradov, National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, Ukraine Abstract Ukrainian revolution frequently called the “Euromaidan” changed Ukrainian society in 120 days and, later, became a regional conflict and a challenge to a global order. This primary social revolution was followed by value and paradigmatic shifts, middle class revolution, and a struggle for human rights, equality, justice, and prosperity. This study examines values and social structure of the Euromaidan. In addition to ethnographic study consisting of participant observations and informal interviewing, data from European Social Survey (2010-2013) and face-to-face survey conducted by an initiative group of sociologists on Maidan were used in order to approach this goal. Results of the study show that values of the Euromaidan (Universalism, Benevolence, Self-Direction, Stimulation, and Security) coincide more with European values, especially those of developed Western and Scandinavian countries, than Ukrainian ones. Furthermore, values of protesters find its reflection in deeply rooted Ukrainian identity. Moreover, Maidan was consisted of three major groups of protesters: “moralists,” “individualists,” -

Topic of Discussion – What Is a Revolution?

Discussion 7-3 US History ~ Chapter 7 Topic Discussions E Lundberg Topic of Discussion – What is a Revolution? Related Topics Chapter Information ~ Ch 7; 4 sections; 35 pages The French Revolution The American Revolution (1775-1783) Major Revolutions throughout history Section 1 ~ The Early Years of the War Pages 194-203 Revolutionary Leaders Section 2 ~ The War Expands Pages 204-211 Section 3 ~ The Path to Victory Pages 212-221 Section 4 ~ The Legacy of the War Pages 222-228 Key Ideas Key Connections - 10 Major (Common) Themes 1. How cultures change through the blending of different ethnic groups. The American Revolution was unique. 2. Taking the land. 3. The individual versus the state. 4. The quest for equity - slavery and it’s end, women’s suffrage etc. The American Revolutionary Leaders were not typical 5. Sectionalism. 6. Immigration and Americanization. revolutionaries. 7. The change in social class. 8. Technology developments and the environment. The Battle for Independence was over home rule and 9. Relations with other nations. 10. Historiography, how we know things. democratic values. Talking Points I Introduction – What is a Revolution A revolution is a fundamental change in political power that takes place over a relatively short period of time. Revolutions have occurred throughout human history for many different reasons. Their results include major changes in culture, economy and socio-political institutions. Here are the ten most influential revolutions. II French Revolution 1. The French Revolution (1789–1799) was a period of radical social and political upheaval in both French and Euro- pean history. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed within three years. -

Rein Taagepera, University of California, Irvine

ESTONIA IN SEPTEMBER 1988: STALINISTS, CENTRISTS AND RESTORATIONISTS Rein Taagepera, University of California, Irvine The situation in Estonia is changing beyond recognition by the month. A paper I gave in late April on this topic needed serious updating for an encore in early June and needs a complete rewrite now, in early September 1988.x By the rime it reaches the readers, the present article will be outdated, too. Either liberalization will have continued far beyond the present stage or a brutal back- lash will have cut it short. Is the scholar reduced to merely chronicling events? Not quite. There are three basic political currents that took shape a year ago and are likely to continue throughout further liberalization and even a crackdown. This framework will help to add analytical perspective to the chronicling. Political Forces in Soviet Estonia Broadly put, three political forces are vying for prominence in Estonia: Stalinists who want to keep the Soviet empire intact, perestroika-minded cen- trists whose goal is Estonia's sovereignty within a loose Soviet confederation, and restorationists who want to reestablish the pre-WWII Republic of Estonia. All three have appreciable support within the republic population. In many cases the same person is torn among all three: Emotionally he might yearn for the independence of the past, rationally he might hope only for a gradual for- marion of something new, and viscerally he might try to hang on to gains made under the old rules. (These gains include not only formal careers but much more; for instance, a skillful array of connections to obtain scarce consumer goods, lovingly built over a long time, would go to waste in an economy of plenty.) 1. -

A Typological Analysis of Collective Political Violence. Das Gupta Kasturi Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1979 A Typological Analysis of Collective Political Violence. Das Gupta Kasturi Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Kasturi, Das Gupta, "A Typological Analysis of Collective Political Violence." (1979). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3431. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3431 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand marking or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing pagefs) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round Mack mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

On the Genealogy of Terrorism

ON THE GENEALOGY OF TERRORISM by Michael Blain 9 July 2005 Department of Sociology Boise State University 1910 University Drive Boise, Idaho 83725-1945 U.S.A. [email protected] The terrorist and the policeman both come from the same basket. Revolution, legality — counter-moves in the same game; forms of idleness at bottom identical. Joseph Conrad, The Secret Agent (1907, ch. 4) ON THE GENEALOGY OF TERRORISM The 9-11-2001 attacks on the World Trade Center, New York City, was a “defining moment,” and not only for George Bush. One can debate whether it was an “act of war,” “asymmetric warfare,” “terrorism,” or a “crime against humanity.” We do know that the Bush administration defined 911 as an act of international terrorism and declared a global war on terrorism (GWOT). Terrorists such as Osama bin Laden were portrayed as implacable foes that had to be tracked down, fought and destroyed.1 Of course, these definitions did not go uncontested. Some people defined those involved in the attack as freedom-fighters, heroes and martyrs engaged in a ‘righteous’ struggle against a villainous ‘superpower.’2 This paper presents the results of a genealogy of the discourse of terror. When and where did this discourse emerge? How has it functioned in power struggles since it emerged? And finally, how has it functioned since the 9-11attacks? It describes how the political concept of terrorism first entered the English language during the French Revolutionary era, and how it has functioned in the changing contexts of British and American imperialism. It argues that describing political actors as ‘terrorists’ rather than as ‘soldiers,’ criminals or insurgents has important social consequences.