Chinaâ•Žs Developing Environmental

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinax Course Notes – Modern History

ChinaX Course Notes – Modern History I transmit, I do not innovate.216 If you copy this document, please do not remove this disclaimer These are the class notes of Dave Pomerantz, a student in the HarvardX/EdX MOOC course entitled ChinaX. My ChinaX id is simply DavePomerantz. First, a very big thank you to Professors Peter Bol and Bill Kirby and Mark Elliot and Roderick MacFarquhar, to the visiting lecturers who appear in the videos and to the ChinaX staff for assembling such a marvelous course. The notes may contain copyrighted material from the ChinaX course. Any inaccuracies are purely my own. Where material from Wikipedia is copied directly into this document, a link is provided. See here. I strongly encourage you to download the PDF file with the notes for the entire course. Sections do not stand alone. Each one refers many times to the others with page numbers and footnotes, helping to connect many of the recurring themes in Chinese history. 216 The Analects 7.1. See page 35. ChinaX Part 9 Communist Liberations Page 305 of 323 Part 9: Communist Liberations 37: Rise of the Communist Party Part 9 Introduction Founded in 1921with only 57 members, the CCP had millions of members by 1949 and ruled all of China. Mao Zedong was only 28 when he attended the first Congress, but he led that ruling party in 1949. John Fairbank wrote that no one in human history ever equaled that accomplishment, given the sheer size and magnificent history of China. How did the CCP come to power? The success was in part the result of early efforts under the Comintern to plan the revolution. -

Social Welfare Under Chinese Socialism

SOCIAL WELFARE UNDER CHINESE SOCIALISM - A CASE STUDY OF THE MINISTRY OF CIVIL AFFAIRS by LINDA WONG LAI YEUK LIN Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the London School of Economics and Political Science University of London May, 1992 - 1 - UMI Number: U615173 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615173 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 n + £ s ^ s F l O U o ABSTRACT All complex human societies make social provisions to ensure the wellbeing and security of their citizens and to facilitate social integration. As in other societies, China's formal welfare system is embedded in its social structure and its informal networks of self help and mutual aid. This thesis explores the development of one of China's major welfare bureaucracies - the Ministry of Civil Affairs and the local agencies which it supervises from 1949, with especial reference to the period between 1978 to 1988. The study begins by surveying the theories, both Western and socialist, that purport to explain the determinants of welfare. -

ON the TEN MAJOR RELATIONSHIPS Excerpt from A

ON THE TEN MAJOR RELATIONSHIPS April 25, 1956 Excerpt from a speech by Mao Zedong at an enlarged meeting of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. X. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CHINA AND OTHER COUNTRIES We have put forward the slo- experience. They all know there gan of learning from other coun- are two aspects to everything, tries. I think we have been right. why do we mention only one? At present, the leaders of some There will always be two aspects, countries are chary and even even ten thousand years from afraid of advancing this slogan. It now. Each age, whether the fu- takes some courage to do so, ture or the present, has its own because theatrical pretensions two aspects, and each individual have to be discarded. has his own two aspects. In It must be admitted that every short, there are two aspects, not nation has its strong points. If just one. To say there is only one not, how can it survive? How can is to be aware of one aspect and it progress? On the other hand, to be ignorant of the other. every nation has its weak points. Some believe that socialism is just perfect, without a single flaw. How can that be true? It must be recognized that there are always two aspects, the strong points and the weak points. The secre- taries of our Party branches, the company commanders and pla- toon leaders of our army have all learned to jot down both aspects in their pocket notebooks, the weak points as well as the strong ones, when summing up their . -

Chinese Communists and Rural Society, 1927-1934

Center for Chinese Studies • CHINA RESEARCH MONOGRAPHS UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY NUMBER THIRTEEN CHINESE COMMUNISTS AND RURAL SOCIETY, 1927-1934 PHILIP C. C. HUANG LYNDA SCHAEFER BELL KATHY LEMONS WALKER Chinese Communists and Rural Society, 1927-1934 A publication of the Center for Chinese Studies University of California, Berkeley, California 94720 Cover Colophon by Shih-hsiang Chen Center for Chinese Studies • CHINA RESEARCH MONOGRAPHS UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY NUMBER THIRTEEN CHINESE COMMUNISTS AND RURAL SOCIETY, 1927-1934 PHILIP C. C. HUANG LYNDA SCHAEFER BELL KATHY LEMONS WALKER Although the Center for Chinese Studies is responsible for the selection and acceptance of monographs in this series, respon sibility for the opinions expressed in them and for the accuracy of statements contained in them rests with their authors. © 1978 by the Regents of the Universit y of California ISBN 0-912966-18-1 Library of Congress Catalog Number 78-620018 Printed in the United States of America $5.00 Contents INTRODUCTION ......... ........... .. .. ..... Philip C. C. Huang INTELLECTUALS, LUMPENPROLETARIANS, WORKERS AND PEASANTS IN THE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT.................. 5 Philip C. C. Huang AGRICULTURAL LABORERS AND RURAL REVOLUTION . 29 Lynda Schaefer Bell THE PARTY AND PEASANT WOMEN 57 Kathy LeMons Walker A COMMENT ON THE WESTE RN LITERATURE. 83 Philip C. C. Huang REFERENCES . 99 GLOSSARY . .. .......... ................. .. .. 117 LIST OF MAPS I. Revolutionary Base Areas and Guerilla Zones in 1934 2 II. The Central Soviet Area in 1934 . 6 III. Xingguo and Surrounding Counties......... .. 10 1 The Jiangxi Period : an Introduction Philip C. C. Huang The Chinese Communist movement in its early years was primarily urban-based. -

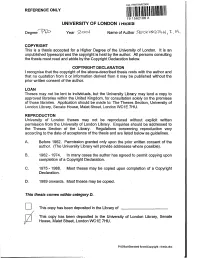

University of London Ihesis

19 1562106X UNIVERSITY OF LONDON IHESIS DegreeT^D^ Year2o o\ Name of Author5&<Z <2 (NQ-To N , T. COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOAN Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the University Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: The Theses Section, University of London Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTON University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the University of London Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The University Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962 - 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. -

Analysis of the Characteristics of Connotation Evolution of Agricultural

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/2516-1652.htm Evolution of Analysis of the characteristics of agricultural connotation evolution of modernization agricultural modernization with Chinese characteristics in the 70 57 years since the founding of Received 8 May 2020 Revised 15 June 2020 New China Accepted 15 June 2020 Yongmu Jiang and Lu Yang School of Economics, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China, and Zhang Xiaolei School of Marxism, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China Abstract Purpose – With the development of social productive forces and the advancement of agricultural practices since the founding of New China, the connotation of agricultural modernization with Chinese characteristics has undergone a process from formation to continuous expansion and deepening. Design/methodology/approach – Its evolution can be roughly divided into four stages: the exploration stage, the formation stage, the establishment stage and the deepening stage. The historical evolution of the connotation of agricultural modernization with Chinese characteristics demonstrates four typical characteristics, namely increasingly scientific logical premise, continuously diversified orientations, increasingly improved core contents and progressively maturing strategies of development. Findings – The achievements of agricultural modernization have laid a solid foundation for China’s industrial modernization and the rapid development of the national economy. Meanwhile, the authors have identified through practical exploration a path of agricultural modernization with Chinese characteristics. In recent years, academic research on the connotation of agricultural modernization with Chinese characteristics has gradually heated up, and relevant achievements have emerged constantly. Originality/value – The Communist Party of China (hereinafter “CPC”) has placed considerable emphasis on agricultural issues and has been committed to promoting agricultural modernization since the founding of New China. -

THE SINO-SOVIET ALLIANCE and CHINA's ENTRY INTO the KOREAN WAR CHEN JIAN State University of New York at Geneseo Working Paper

THE SINO-SOVIET ALLIANCE AND CHINA’S ENTRY INTO THE KOREAN WAR CHEN JIAN State University of New York at Geneseo Working Paper No. 1 Cold War International History Project Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Washington, D.C. June 1992 THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES CHRISTIAN F. OSTERMANN, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. The project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to accelerate the process of integrating new sources, materials and perspectives from the former “Communist bloc” with the historiography of the Cold War which has been written over the past few decades largely by Western scholars reliant on Western archival sources. It also seeks to transcend barriers of language, geography, and regional specialization to create new links among scholars interested in Cold War history. Among the activities undertaken by the project to promote this aim are a periodic BULLETIN to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to Cold War history; a fellowship program for young historians from the former Communist bloc to conduct archival research and study Cold War history in the United States; international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars; and publications. -

The 20Th Party Congress of the Soviet Union

Parallel History Project on NATO and the Warsaw Pact The Cold War History of Sino-Soviet Relations June 2005 The 20th Party Congress of the Soviet Union and Mao Zedong’s Tortuous Path by Lin Yunhui* With regard to socialist development in China, Mao Zedong once said,“at the beginning of building a new state, we just copied the Soviet Union as there was no path to follow.” 1 He also said “during the first three years of recovery after Liberation, we were quite confused about development. Later on, when we drew up our first five-year plan, we were still not very clear about it, so we basically had to do what the Soviet Union did. But we were not satisfied and felt uneasy.2 “In On the Ten Major Relationships, published in April 1956, we began to set up our own line on development. The principles of development were the same as the Soviet Union’s but there were some differences in method. We had our own ideas.”3 “Our own line on development” must have directly originated from the exposure of Stalin’s mistakes at the 20th Party Congress of the Soviet Union. However, as circumstances changed, Mao’s view’s on the 20th Party Congress also changed a lot. This directly influenced the theory and practice of China’s own brand of socialism. Taking the Soviet Union as a Warning, Follow China’s Own Path According to Bo Yibo’s recollections, all that happened after Stalin’s death - including the exposure of Beria, the reversal of a series of unjust and wrong verdicts, the strengthening of agriculture, debates about the heavy industry centered policy, the change of attitude toward Yugoslavia and the rapid replacement of the successor chosen by Stalin - had made the Central Committee of the CPC aware of the problems in Stalin’s and Soviet Union’s experience. -

China's Developing Environmental Law: Policies, Practices and Legislation

Boston College International and Comparative Law Review Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 4 12-1-1983 China’s Developing Environmental Law: Policies, Practices and Legislation Bruce L. Ottley Charles Valauskas Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/iclr Part of the Environmental Law Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Bruce L. Ottley & hC arles Valauskas, China’s Developing Environmental Law: Policies, Practices and Legislation, 6 B.C. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 81 (1983), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/iclr/vol6/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. China's Developing Environmental Law: Policies, Practices and Legislation by Bruce L. Ottley* and Charles C. Valauskas** I. INTRODUCTION InJuly 1979 the People's Republic of China took a major step toward creating a Western style legal system when it enacted seven new laws.! Since that time, the Chinese have given increasing attention to the role of law2 as a means of regulating conduct. The National People's Congress has adopted subsequent laws, regulations and procedures aimed at establishing a general legal system for the country and regulating foreign investment.3 Amid the rapid developments taking place in Chinese law, American lawyers, scholars and business people have focused most of their attention on the legal aspects of normalization of relations between the United States and China. -

PEKING REVIEW, Peking (37), Chtno Post Office Registrotion No, 2-/2 Printrd Ln the People's Republic of Chino the WEEK

PEKI Febru'r725''e7' IEW IL Comrade, Hua !(uo-feng in llunan 4, Mechan )zation: Fundamental 'Agriculture A Wty Out for ,& Frsnce's New Strotegic Concept PEKING Vol. Z), No. 9 Februory 25, 19Tl REVIEW Published ln English, French, Spanish, ,L 4 A.* Japanese and German editions CO NTE NTS THE WEEI( Go All Out to lmprove Roilwoy Tronsport . Get-Together in Celebrotion of Spring Festivol ' Premier Huo Congrotulotes President Dooud Diplomotic Relotions Between Chino ond Liberio Estoblished ARTICLES AND DOCUMENIS Comrode Huo Kuo.feng in Hunon * Jeh Huo 5 2nd Notionol Leorn-From-Tochoi Conference (lV): Mechonizotion; Fundomentqt Woy Out for Agriculture-Our Correspondent Chou Chin 11 Foreign Trode: Why the "Gong of Four" Creoted Confusion-Kuo Chi 16 Kwongsi: Revolution in Heolth Work (ll): Borefoot Doctors ond Co-operotive Medicol System-Our Correspondents Huo Sheng ond Hsiong Juig 19 Heolth Service in o Remote Mountoin Villoge 23 Frsnce's New Shotegic Concept 25 Newsletter F.rom Bonn: Munich Lesson Must Not 8e Forgotten-Hsinhuo Cor- respondents 27 ROUND THE WORTD "Closs Struggle" (U.S.A.): On the Theory of Three?L--- Worldsr.r- r r Qator: Oil Notionolized Brozilr No Suspension of Nucleor Agreement With Bonn U.N. Security Council : lnvosion of Benin Condemned Austrolio: Vile Soviet Sociol-lmperiolist Acts C.M.E.A.: Moscow Roises Oil Price Agoin ON THE HOME FRONT Rich Repertoire During the Spring Festivol Jonuory Cool Production Plon Overfulfilled A Big Fhosphosiderite Mine Publirhcd every Fridoy by PEKING REVIEW, Peking (37), Chtno Post Office Registrotion No, 2-/2 Printrd ln the People's Republic of Chino THE WEEK Go All Out to lmprovc which uras necently published tralized leadership of the Party Railway Transport and Chairman Hua's important committees of the various prov- speech at the Second National inces, municipalities and auton- A national conference on Conlerence on karning From omous regions, take class strug- railway work was recently con- Taehai in Agriculture. -

PEKING REVIEW, Peking (37), Chino Post Office Registrotion No, 2-922 Printed in the People's Republic of Chino

PEKI 1 lonuory l, lm (l]I IHE PL TEll trl[J0[ REL[Il0llSHlPS 4 prll 2t, 1956 l-portant Speech by A Chairman Hua Kuo-feng Advonce From Victory to Victory -- 1977 New Yeor's Doy editoriol by "Renmin Riboo," 4L "Jiefongjun "Hongqi" ond Boo" Vol. 20, No. 1 Jonuory lg'f, PEKING .1, REVIEW Published in English, French, Spanish, Japanese and German editions ,A 4. [^.fu CO NTE NTS THE WEEK : Eighty-Third Anniversory of Choirmon Moo Tsetung's Bi*hdoy Morked. ' Choirmon Huo Receives Representotives Attending Notionol Leorn-From-Tochoi Conference ARTICLES AND DOCUMENTS On the Ten Mojor Relotionships - Moo Tsetung 10 Eternol Glory to Choirmon Moo Tsetung - Full-length colour documentory on mournrng the deoth of the greot leqder ond teocher Choirmon Moo Tsetung 26 Photo Exhibition "Choirmon Moo Will Live For Ever in Our Heorts" 27 \ Speech ot the Second Notionol Conlerence on Leorning From fochoi in Agri' Centrol Committee of the Com- culture - Huo Kuo-feng, Choirmon of the munist Porty of Chino 31 Advonce From Victory to Vittory New Yeor'5 Doy editoriol by Renmi,n -1977 Ribao, Hongqi ond Jiefangiun Boo 45 . ROUND THE WORLD 48 Egypt ond Syrio: Estoblishing o Unified Politicol Leodership OPEC: Decision to Roise Oil Price Published every Fridqy by PEKING REVIEW, Peking (37), Chino Post Office Registrotion No, 2-922 Printed in the People's Republic of Chino i. tI' r %""%Za% '%%% Eighty-Third lnniuersary ol Ghairman ilao Tsetung's Birthday ilarked ECEMBER 26, 1976 was the 83rd anniver- rejected the suggestion. This fully revealed the sary of the birthday of our great leader deep-seated hatred this bunch of anti-Party and teacher Chairman Mao Tsetung. -

What Is Labour?

PARADOXES OF LABOUR REFORM Chinese Worlds Chinese Worlds publishes high-quality scholarship, research monographs, and source collections on Chinese history and society from 1900 in the 21st century. 'Worlds' signals the ethnic, cultural, and political multiformity and regional diversity of China, the cycles of unity and division through which China's modern history has passed, and recent research trends toward regional studies and local issues. It also signals that Chineseness is not contained within terri torial borders - some migrant communities overseas are also 'Chinese Worlds'. Other ethnic Chinese communities throughout the world have evolved new identities that transcend Chineseness in its established senses. They too are covered by this series. The editors see them as part of a political, economic, social, and cultural continuum that spans the Chinese mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, South-East Asia, and the world. The focus of Chinese Worlds is on modern politics and society and his tory. It includes both history in its broader sweep and specialist mono graphs on Chinese politics, anthropology, political economy, sociology, education, and the social-science aspects of culture and religions. The Literary Field of New Fourth Army Twentieth-Century China Communist Resistance along the Edited by Michel Hockx Yangtze and the Huai, 1938-1941 Chinese Business in Malaysia Gregor Benton Accumulation, Ascendance, A Road is Made Accommodation Communism in Shanghai Edmund Terence Gomez 1920-1927 Internal and International Steve Smith