The Spread of Olives (Olea Sp.) on Wagga Wagga Campus I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Olea Europaea L. a Botanical Contribution to Culture

American-Eurasian J. Agric. & Environ. Sci., 2 (4): 382-387, 2007 ISSN 1818-6769 © IDOSI Publications, 2007 Olea europaea L. A Botanical Contribution to Culture Sophia Rhizopoulou National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Department of Biology, Section of Botany, Panepistimioupoli, Athens 157 84, Greece Abstract: One of the oldest known cultivated plant species is Olea europaea L., the olive tree. The wild olive tree is an evergreen, long-lived species, wide-spread as a native plant in the Mediterranean province. This sacred tree of the goddess Athena is intimately linked with the civilizations which developed around the shores of the Mediterranean and makes a starting point for mythological and symbolic forms, as well as for tradition, cultivation, diet, health and culture. In modern times, the olive has spread widely over the world. Key words: Olea • etymology • origin • cultivation • culture INTRODUCTION Table 1: Classification of Olea ewopaea Superdivi&on Speimatophyta-seed plants Olea europaea L. (Fig. 1 & Table 1) belongs to a Division Magnohophyta-flowenng plants genus of about 20-25 species in the family Oleaceae [1-3] Class Magn olio psi da- dicotyledons and it is one of the earliest cultivated plants. The olive Subclass Astendae- tree is an evergreen, slow-growing species, tolerant to Order Scrophulanale- drought stress and extremely long-lived, with a life Family Oleaceae- olive family expectancy of about 500 years. It is indicative that Genus Olea- olive Species Olea europaea L. -olive Theophrastus, 24 centuries ago, wrote: 'Perhaps we may say that the longest-lived tree is that which in all ways, is able to persist, as does the olive by its trunk, by its power of developing sidegrowth and by the fact its roots are so hard to destroy' [4, book IV. -

Molecular Characterization of Some Selected Wild Olive (Olea Oleaster

TARIM B İLİMLER İ DERG İSİ 2009, 15 (1) 14-19 ANKARA ÜN İVERS İTES İ Z İRAAT FAKÜLTES İ Molecular Characterization of Some Selected Wild Olive ( Olea oleaster L.) Ecotypes Grown in Turkey Mücahit Taha ÖZKAYA 1 Erkan ERGÜLEN 2 Salih ÜLGER 3 Nejat ÖZİLBEY 4 Geli ş Tarihi: 31.10.2008 Kabul Tarihi: 13.04.2009 Abstract: The wild olive subspecies oleaster called “Karadelice” in Turkish is a small tree or bush of rather irregular growth, with thorny branches and oppositely positioned oblong pointed leaves, dark grayish- green on the leaf surface and, in the early growth state, hoary on the lower surface with whitish scales. Generally, it is used as a dwarf rootstock; however, it has some grafting incompatibility with certain important olive cultivars. Some wild olive plants were selected from the village Kayadibi, 20 km distant from the city of İzmir in Turkey. This region is a very unique place for this type of wild olive. These ecotypes were differentiated by molecular markers using RAPD-PCR. Since they can be used as a dwarf rootstock, the correlations with some important olive cultivars were analyzed. For that reason Ayvalık cv, which is the most important olive cultivar for olive oil production was used primarily. Since Ayvalık cv and KD-8 are 97% similar, it was expected that they may have grafting compability. In the second part of the study, the comparison were done with Memecik and Tav şan Yüre ği cultivars which are important olive oil and table olive cultivars, respectively. Since Memecik and Tav şan Yüre ği were 100% similar therefore, it was considered that they may have more grafting compability with oleasters KD-3 and KD-8. -

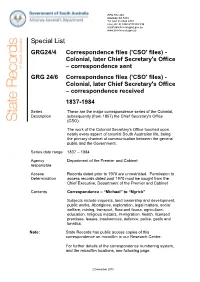

Michael” to “Myrick”

GPO Box 464 Adelaide SA 5001 Tel (+61 8) 8204 8791 Fax (+61 8) 8260 6133 DX:336 [email protected] www.archives.sa.gov.au Special List GRG24/4 Correspondence files ('CSO' files) - Colonial, later Chief Secretary's Office – correspondence sent GRG 24/6 Correspondence files ('CSO' files) - Colonial, later Chief Secretary's Office – correspondence received 1837-1984 Series These are the major correspondence series of the Colonial, Description subsequently (from 1857) the Chief Secretary's Office (CSO). The work of the Colonial Secretary's Office touched upon nearly every aspect of colonial South Australian life, being the primary channel of communication between the general public and the Government. Series date range 1837 – 1984 Agency Department of the Premier and Cabinet responsible Access Records dated prior to 1970 are unrestricted. Permission to Determination access records dated post 1970 must be sought from the Chief Executive, Department of the Premier and Cabinet Contents Correspondence – “Michael” to “Myrick” Subjects include inquests, land ownership and development, public works, Aborigines, exploration, legal matters, social welfare, mining, transport, flora and fauna, agriculture, education, religious matters, immigration, health, licensed premises, leases, insolvencies, defence, police, gaols and lunatics. Note: State Records has public access copies of this correspondence on microfilm in our Research Centre. For further details of the correspondence numbering system, and the microfilm locations, see following page. 2 December 2015 GRG 24/4 (1837-1856) AND GRG 24/6 (1842-1856) Index to Correspondence of the Colonial Secretary's Office, including some newsp~per references HOW TO USE THIS SOURCE References Beginning with an 'A' For example: A (1849) 1159, 1458 These are letters to the Colonial Secretary (GRG 24/6) The part of the reference in brackets is the year ie. -

Thrf-2019-1-Winners-V3.Pdf

TO ALL 21,100 Congratulations WINNERS Home Lottery #M13575 JohnDion Bilske Smith (#888888) JohnGeoff SmithDawes (#888888) You’ve(#105858) won a 2019 You’ve(#018199) won a 2019 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 KymJohn Tuck Smith (#121988) (#888888) JohnGraham Smith Harrison (#888888) JohnSheree Smith Horton (#888888) You’ve won the Grand Prize Home You’ve(#133706) won a 2019 You’ve(#044489) won a 2019 in Brighton and $1 Million Cash BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 GaryJohn PeacockSmith (#888888) (#119766) JohnBethany Smith Overall (#888888) JohnChristopher Smith (#888888)Rehn You’ve won a 2019 Porsche Cayenne, You’ve(#110522) won a 2019 You’ve(#132843) won a 2019 trip for 2 to Bora Bora and $250,000 Cash! BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 Holiday for Life #M13577 Cash Calendar #M13576 Richard Newson Simon Armstrong (#391397) Win(#556520) a You’ve won $200,000 in the Cash Calendar You’ve won 25 years of TICKETS Win big TICKETS holidayHolidays or $300,000 Cash STILL in$15,000 our in the Cash Cash Calendar 453321 Annette Papadulis; Dernancourt STILL every year AVAILABLE 383643 David Allan; Woodville Park 378834 Tania Seal; Wudinna AVAILABLE Calendar!373433 Graeme Blyth; Para Hills 428470 Vipul Sharma; Mawson Lakes for 25 years! 361598 Dianne Briske; Modbury Heights 307307 Peter Siatis; North Plympton 449940 Kate Brown; Hampton 409669 Victor Sigre; Henley Beach South 371447 Darryn Burdett; Hindmarsh Valley 414915 Cooper Stewart; Woodcroft 375191 Lynette Burrows; Glenelg North 450101 Filomena Tibaldi; Marden 398275 Stuart Davis; Hallett Cove 312911 Gaynor Trezona; Hallett Cove 418836 Deidre Mason; Noarlunga South 321163 Steven Vacca; Campbelltown 25 years of Holidays or $300,000 Cash $200,000 in the Cash Calendar Winner to be announced 29th March 2019 Winners to be announced 29th March 2019 Finding cures and improving care Date of Issue Home Lottery Licence #M13575 2729 FebruaryMarch 2019 2019 Cash Calendar Licence ##M13576M13576 in South Australia’s Hospitals. -

Place Names of South Australia: W

W Some of our names have apparently been given to the places by drunken bushmen andfrom our scrupulosity in interfering with the liberty of the subject, an inflection of no light character has to be borne by those who come after them. SheaoakLog ispassable... as it has an interesting historical association connectedwith it. But what shall we say for Skillogolee Creek? Are we ever to be reminded of thin gruel days at Dotheboy’s Hall or the parish poor house. (Register, 7 October 1861, page 3c) Wabricoola - A property North -East of Black Rock; see pastoral lease no. 1634. Waddikee - A town, 32 km South-West of Kimba, proclaimed on 14 July 1927, took its name from the adjacent well and rock called wadiki where J.C. Darke was killed by Aborigines on 24 October 1844. Waddikee School opened in 1942 and closed in 1945. Aboriginal for ‘wattle’. ( See Darke Peak, Pugatharri & Koongawa, Hundred of) Waddington Bluff - On section 98, Hundred of Waroonee, probably recalls James Waddington, described as an ‘overseer of Waukaringa’. Wadella - A school near Tumby Bay in the Hundred of Hutchison opened on 1 July 1914 by Jessie Ormiston; it closed in 1926. Wadjalawi - A tea tree swamp in the Hundred of Coonarie, west of Point Davenport; an Aboriginal word meaning ‘bull ant water’. Wadmore - G.W. Goyder named Wadmore Hill, near Lyndhurst, after George Wadmore, a survey employee who was born in Plymouth, England, arrived in the John Woodall in 1849 and died at Woodside on 7 August 1918. W.R. Wadmore, Mayor of Campbelltown, was honoured in 1972 when his name was given to Wadmore Park in Maryvale Road, Campbelltown. -

List of Plant Species List of Plant Species

List of plant species List of Plant Species Contents Amendment history .......................................................................................................................... 2 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Application ........................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Relationship with planning scheme ..................................................................................... 3 1.3 Purpose ............................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Aim ...................................................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Who should use this manual? ............................................................................................. 3 2 Special consideration ....................................................................................................................... 3 3 Variations ......................................................................................................................................... 4 4 Relationship ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Appendix A – Explanatory notes & definitions ....................................................................................... -

Influence of Olea Oleaster Leaves Extract on Some Physiological Parameters in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats

World Applied Sciences Journal 36 (1): 16-28, 2018 ISSN 1818-4952 © IDOSI Publications, 2018 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.wasj.2018.16.28 Influence of Olea oleaster Leaves Extract on Some Physiological Parameters in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats Mesfer A.M. Al-Thebaiti and Talal A. Zari Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, King Abdulaziz University, P.O. Box: 80203, Jeddah 21589, Saudi Arabia Abstract: The current study was intended to investigate the influence of wild olive (Olea oleaster) leaves extract on some physiological parameters in streptozotocin (STZ) induced diabetes in male Wistar rats after four weeks. The experimental rats were divided into four groups. Rats of the first group were served as normal controls. Rats of the second group were diabetic controls. Rats of the third group were diabetic rats, treated with olive leaves extract. Rats of the fourth group were non diabetic rats, treated with olive leaves extract. In diabetic rats of the second group, the levels of serum glucose, triglycerides, low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), very low density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL), creatine kinase (CK) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were significantly increased. However, the level of serum albumin was significantly decreased. Administration of olive leaves extract improved most observed physiological changes. Therefore, the results of this study proved the physiologically effective components of wild olive leaves extract which exert protective influence on diabetic rats. Key words: Olea Oleaster Olive Leaves Diabetes Streptozotocin Blood Rats INTRODUCTION resistance [6] and in chronic treatments causes anorexia nervosa, fatty liver and brain atrophy [7]. DM may be Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a metabolic syndrome induced in experimental animals by destruction of -cells distinguished by chronic hyperglycemia with of the pancreas with a single injection of streptozotocin disturbances of carbohydrate, protein and lipid (STZ). -

Cit!J If Mefaije..Ftertt-'Y'e ~T-Er

Jtems recomluJ!,u<J~"f"r inc[usicn on a Cit!J ifMefaiJe..ftertt-'Y'e ~t-er ';Dp_artmeat ff CiYJ Pfannitf!p Sp_temPer l'SJ • • • • THE CITY OF ADELAIDE HERITAGE STUDY ITFMS RECOMMENDED FOR INCLUSION ON A CITY OF ADELAIDE HERITAGE REGISTER BY THE LORD MAYOR'S HERITAGE ADVISORY COMMITTEE VOLlME 1 GAWLER WARD (ITEMS WITHIN TOWN ACRES) VOLlME 2 HINDMARSH WARD (ITEMS WITHIN TOWN ACRES) VOLlME 3 GREY WARD (ITEMS WITHIN TOWN ACRES) VOLlME 4 YOUNG WARD (ITEMS WITHIN TOWN ACRES) VOLlME 5 ROBE WARD (ITEMS WITHIN TOWN ACRES) VOLlME 6 MACDONNELL WARD (ITEMS WITHIN TOWN ACRES) VOLlME 7 PARK IANDS (ALL ITEMS oursIDE THE TERRACES - NOT WITHIN TOON ACRES) VOLU1E 8 SUMMARY ANALYSIS OF THE PROPOSED CITY OF ADELAIDE HERITAGE REGISTER. Department of City Planning September 1983. MC: 2 :DCP lOD/C (26/9/83) VOLlME 7 PARK LANDS (ALL ITavtS ourSIDE THE TERRACES - NOT WITHIN TOWN ACRES) 2:DCP10D/D7 TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLlME 7 - PARK LANDS (ALL ITEMS OUTSIDE THE TERRACES - NOT WI THIN TOWN ACRES) PAGE MAP OF THE CITY OF ADELAIDE Showing Location of Items Within the Park Lands (Outside the Terraces - Not Within Town Acres) 1 S lMMARY DOCUMENTATION OF ITEMS 2 Item Number as------ appearing in Volume 8 Table Item and Address 312 2 Parliament House North Terrace 313 4 Constitutional Museum North Terrace 314 6 S.A. Museum, East Wing North Terrace 315 8 S.A. Museum, North Wing North Terrace 316 10 Fmr. Mounted Police Barracks, Armoury and Arch Off North Terrace 317 13 Fmr. Destitute Asylum (Chapel, Store, Lying-in Hospital & Female Section) Kintore Avenue 318 18 State Library - Fmr. -

Rethinking Modern Architecture – Caroline Cosgrove

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Flinders Academic Commons Rethinking Modern Architecture – Caroline Cosgrove Rethinking Modern Architecture: HASSELL’s Contribution to the Transformation of Adelaide’s Twentieth Century Urban Landscape Caroline Cosgrove Abstract There has been considerable academic, professional and community interest in South Australia’s nineteenth century built heritage, but less in that of the state’s twentieth century. Now that the twenty-first century is in its second decade, it is timely to attempt to gain a clearer historical perspective on the twentieth century and its buildings. The architectural practice HASSELL, which originated in South Australia in 1917, has established itself nationally and internationally and has received national peer recognition, as well as recognition in the published literature for its industrial architecture, its education, airport, court, sporting, commercial and performing arts buildings, and the well-known Adelaide Festival Centre. However, architectural historians have generally overlooked the practice’s broader role in the development of modern architecture until recently, with the acknowledgement of its post-war industrial work.1 This paper explores HASSELL’s contribution to the development of modern architecture in South Australia within the context of growth and development in the twentieth century. It examines the need for such studies in light of heritage considerations and presents an overview of the firm’s involvement in transforming the urban landscape in the city and suburbs of Adelaide. Examples are given of HASSELL’s mid-twentieth century industrial, educational and commercial buildings. This paper has been peer reviewed 56 FJHP – Volume 27 ‐2011 Figure 1: Adelaide’s urban landscape with the Festival Centre in the middle distance. -

T.C Istanbul Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Coğrafya Anabilim Dali

T.C İSTANBUL ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ COĞRAFYA ANABİLİM DALI DOKTORA TEZİ KUŞADASI, BODRUM VE PİRE(YUNANİSTAN) YAT LİMANLARININ TURİZM COĞRAFYASI AÇISINDAN KARŞILAŞTIRILMASI OLCAY ŞEMİEOĞLU 2502918894 DANIŞMAN: DOÇ.DR.SÜHEYLA BALCI AKOVA İSTANBUL 2006 TEZ ONAY SAYFASI II ÖZ Kuşadası, Bodrum ve Pire (Yunanistan) yat limanlarının turizm coğrafyası açısından karşılaştırılması adındaki bu çalışmada, ülkemizde yat turizminin başlıca merkezleri olan Bodrum, Kuşadası bölgelerinin ve yat turizminde daha gelişmiş olarak kabul edilen Pire bölgesinin doğal çekicilikleri, zengin tarihi ve yat limanları incelenmektedir. Çalışmamızda araştırılan Bodrum (Karada-Milta) ve Kuşadası (Setur) Marinaları, modern alt yapıları ve uygun ücretleri ile Akdeniz’de seyir halinde olan yerli ve yabancı yatlara birinci sınıf hizmet veren marinalardır. Kuşadası, Bodrum ve Pire yat limanları dünyanın çeşitli bölgelerinden gelen turistleri coğrafi şartlarının sağladığı avantajlardan dolayı etkilemektedirler. Bodrum ve Kuşadası bölgesi tüm dünyadaki diğer tarihi ve arkeolojik yöreler içinde en tanınmış ve bilinen eserlere ve yerlere sahiptir. Yatlarıyla gelen ziyaretçiler Bodrum Milta Marina ve Kuşadası Setur Marina’da gereksindikleri her tür hizmeti almaktadırlar. Bu yüzden tez konumuz olan marinalar Ege ve Akdeniz’de yelken açanlar tarafından tercih edilmektedir. Yat turizminin daha üst noktalara ulaşması için gerekli önlemler alındığında, Kuşadası Setur ve Bodrum Milta Marinalarının gelişen Akdeniz Yat turizmi dünyasında en önde kabul edilen İspanya, Fransa ve İtalya’daki marinalardan daha fazla ilerleyerek, her geçen yıl turizm alanında dünya pazarındaki payını artırarak bir çekim merkezi haline gelen Türkiye’nin en popüler marinaları olarak kabul edileceklerdir. ABSTRACT In the study ‘Comparison of Kuşadası, Bodrum and Piraeus (Greece) Marinas in terms of Tourism Geography’ the natural beauty, rich history and marinas of Bodrum, Kuşadası, accepted as the yacht tourism centers in Turkey, and Piraeus which is considered more developed in yacht tourism is analysed. -

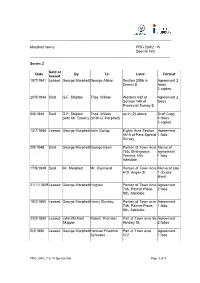

Morphett Family PRG 239/2 -15 Special Lists ______

________________________________________________________________________ Morphett family PRG 239/2 -15 Special lists ______________________________________________________________________ Series 2 S Sold or Date By To Land Format leased 19/7/1841 Leased George Morphett George Alston Section 2086 in Agreement 2 District B folios 2 copies 20/5/1844 Sold G.F. Shipton Thos. Wilson Western half of Agreement 2 Section 145 of folios Provincial Survey B 5/6/1844 Sold G.F. Shipton Thos. Wilson as in (2) above Draft Copy (with Mr. Brown) (With G. Morphett) 4 folios 2 copies 13/7/1844 Leased George Morphett John Gollop Eighty Acre Section Agreement 5515 of Para Special 1 folio Survey 2/9/1848 Sold George Morphett George Bean Portion of Town Acre Memo of 755, Strangways agreement Terrace, Nth. 1 folio Adelaide. 17/5/1849 Sold Mr. Morphett Mr. Raymond Portion of Town Acre Memo of sale 410, Angas St. 1 double sheet 21/11/1849 Leased George Morphett Hughes Portion of Town Acre Agreement 746, Palmer Place, 2 folio Nth. Adelaide 19/2/1850 Leased George Morphett Henry Stuckey Portion of Town acre Agreement 746, Palmer Place, 1 folio Nth. Adelaide. 23/2/1850 Leased John Michael Robert Thornber Part of Town acre 56, Agreement Skipper Hindley St. 2 folios 2/3/1850 Leased George Morphett Herman Friedrick Part of Town acre Agreement Schrader 572 1 folio PRG 239/2, 7 & 15 Special lists Page 1 of 9 ________________________________________________________________________ 30/1/1854 Leased George Morphett Nathaniel Summers Part of Town acre Ag reement 755, Strangways 1 folio Terrace, Nth. Adelaide 14/6/1850 Leased Robert Thornber John Dickins + Part of Town acre 56 Agreement George Griffin 1 double sheet 26/6/1850 Sold George Morphett Henry Jessop Part of Town acre Memo of 998, Melbourne St. -

Wild Olive Tree Mapping: Extent, Distribution and Basic Attributes of Wild Olive Tree in Al-Baha Region, Saudi Arabia, Using Remote Sensing Technology

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 SJIF (2019): 7.583 Wild Olive Tree Mapping: Extent, Distribution and Basic Attributes of Wild Olive Tree in Al-Baha Region, Saudi Arabia, Using Remote Sensing Technology III. Distribution and mapping of wild olive tree according to neighbouring tree species Abdullah Saleh Al-Ghamdi Department of Biology, College of Sciences, Al-Baha University, P.O. Box 400, Al-Baha 31982, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia abdullah.saleh.alghamdi[at]gmail.com Abstract: This study provides a detailed overview of the extent and distribution of wild olive trees in Al-Baha region according to neighbouring tree species. The study area was concentrated along the Sarah mountainat Al-Baha region, encompassing the districts Al-Qura, Al-Mandaq, Al-Baha, the southern part of Baljurashi, and a small portion of Qelwa, Mekhwa, and Al-Aqiq districts. This indicates that the wild olive prefers to grow in high foggy mountain conditions, which a previous study determined as a medium-high vegetation density zone. The information extracted from the high-resolution PLEIADES satellite image reveals that the districts of Al- Mandaq and Al-Baha have a higher density of wild olives with more juniper neighbouring. On the other hand, the districts of Al-Qura and Al-Baljurashi have a lower density of wild olives but more acacia neighbouring. Meanwhile, the districts of Al-Aqiq, Qelwa, and Mekhwa have the least density of wild olives with more juniper neighbouring; however, Qelwa has more ‘other’ species neighbouring. Further analysis of the imagery by automatic measurement of olive trees found that the wild olive tree associates its occurrence with certain species.