Communism, Subaltern Studies and Postcolonial Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samir Gandesha1 the Aesthetic Politics of Hegemony

Studi di estetica, anno XLVI, IV serie, 3/2018 ISSN 0585-4733, ISSN digitale 1825-8646, DOI 10.7413/18258646066 Samir Gandesha1 The aesthetic politics of hegemony Abstract In this article, it is argued that Gramsci’s conception of hegemony ought to be located not simply in the theory and praxis of Leninism but also in Gramsci’s read- ing of Machiavelli. By situating such a reading in relation to Nietzsche’s notion of will to power, it is possible to defend Gramsci’s political theory against some of the criticisms leveled by those who decry the “hegemony of hegemony”. Such a reading of the concept of hegemony enables us to understand the idea of “com- mon sense” as oriented towards the distribution and redistribution of the sensible. Keywords Aesthetics, Gramsci, Hegemony 1. Introduction In the introduction to our book Aesthetic Marx (2017), Johan Hartle and I point out that there is one main problem with the Marxological approach to the aesthetic dimensions of Marx’s writings: the classical understanding of the discipline of aesthetics that is presupposed by such exegetical approaches must also be interrogated. “Aesthetics” is normally understood as a philosophical discipline that concerns the conditions for the possibility of judgments of taste, as a specific ra- tionality that maintains its own autonomy, its own purposeless pur- posiveness, against contending and competing the spheres of value (the epistemic, the moral), and that deals with normative criteria in order to evaluate forms of experience and artistic developments on 1 [email protected]. I would like to thank professor Stefano Marino for his extremely helpful suggestions and assistance with this article. -

Fall 2005 Newsletter of the ASA Comparative and Historical Sociology Section Volume 17, No

________________________________________________________________________ __ Comparative & Historical Sociology Fall 2005 Newsletter of the ASA Comparative and Historical Sociology section Volume 17, No. 1 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ From the Chair: State of the CHS Union SECTION OFFICERS 2005-2006 Richard Lachmann SUNY-Albany Chair Richard Lachmann Columns of this sort are the academic equivalents of State SUNY-Albany of the Union speeches, opportunities to say that all is well and to take credit for the good times. Chair-Elect William Roy I can’t (and won’t) take credit for the healthy state of com- University of California-Los Angeles parative historical sociology but I do want to encourage all of us to recognize the richness of our theoretical discus- sions and the breadth and depth of our empirical work. The Past Chair Jeff Goodwin mid-twentieth century revolution in historiography—the New York University discovery and creative interpretation of previously ignored sources, many created by historical actors whose agency had been slighted and misunderstood—has been succeeded Secretary-Treasurer by the recent flowering of comparative historical work by Genevieve Zubrzycki sociologists. University of Michigan We can see the ambition and reach of our colleagues’ work Council Members in the research presented at our section’s panels in Phila- Miguel A. Centeno, Princeton (2007) delphia and in the plans for sessions next year (see the call Rebecca Jean Emigh, UCLA (2006) for papers elsewhere in this newsletter). The Author Meets Marion Fourade-Gourinchas, Berkeley (2008) Critics panel on Julia Adams, Lis Clemens, and Ann Or- Fatma Muge Gocek, U Michigan (2006) Mara Loveman, UW-Madison (2008) loff’s Remaking Modernity: Politics, History, and Sociol- James Mahoney, Northwestern (2007) ogy was emblematic of how our field’s progress got ex- pressed at the Annual Meeting. -

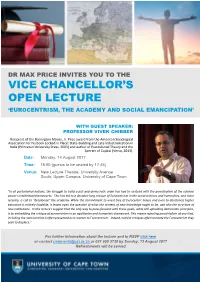

Vice Chancellor's Open Lecture

DR MAX PRICE INVITES YOU TO THE VICE CHANCELLOR’S OPEN LECTURE ‘EUROCENTRISM, THE ACADEMY AND SOCIAL EMANCIPATION’ WITH GUEST SPEAKER: PROFESSOR VIVEK CHIBBER Recipient of the Barrington Moore, Jr. Prize award from the American Sociological Association for his book Locked in Place: State-Building and Late Industrialization in India (Princeton University Press, 2003) and author of Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital (Verso, 2013). Date: Monday, 14 August 2017 Time: 18:00 (guests to be seated by 17:45) Venue: New Lecture Theatre, University Avenue South, Upper Campus, University of Cape Town "In all postcolonial nations, the struggle to build a just and democratic order has had to contend with the parochialism of the colonial power’s intellectual frameworks. This has led to a decades-long critique of Eurocentrism in the social sciences and humanities, and more recently, a call to “decolonize” the academy. While the commitment to wrest free of Eurocentric biases and even to decolonize higher education is entirely laudable, it leaves open the question of what the content of new knowledge ought to be, and also the structure of new institutions. In this lecture I suggest that the only way to press forward with these goals, while still upholding democratic principles, is by embedding the critique of eurocentrism in an egalitarian and humanistic framework. This means rejecting parochialism of any kind, including the nativism that is often presented as a counter to Eurocentrism. Indeed, nativist critiques often recreate the Eurocentrism they seek to displace." For further information about the lecture and to RSVP click here or contact [email protected] or 021 650 3730 by Sunday, 13 August 2017 Refreshments will be served . -

SOCIOLOGY 9191A Social Science in the Marxian Tradition Fall 2020

SOCIOLOGY 9191A Social Science in the Marxian Tradition Fall 2020 DRAFT Class times and location Wednesday 10:30am -12:30pm Virtual synchronous Instructor: David Calnitsky Office Hours by appointment Department of Sociology Office: SSC 5402 Email: [email protected] Technical Requirements: Stable internet connection Laptop or computer Working microphone Working webcam “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.” – Karl Marx That is the point, it’s true—but not in this course. This quote, indirectly, hints at a deep tension in Marxism. If we want to change the world we need to understand it. But the desire to change something can infect our understanding of it. This is a pervasive dynamic in the history of Marxism and the first step is to admit there is a problem. This means acknowledging the presence of wishful thinking, without letting it induce paralysis. On the other hand, if there are pitfalls in being upfront in your desire to change the world there are also virtues. The normative 1 goal of social change helps to avoid common trappings of academia, in particular, the laser focus on irrelevant questions. Plus, in having a set of value commitments, stated clearly, you avoid the false pretense that values don’t enter in the backdoor in social science, which they often do if you’re paying attention. With this caveat in place, Marxian social science really does have a lot to offer in understanding the world and that’s what we’ll analyze in this course. The goal is to look at the different hypotheses that broadly emerge out of the Marxian tradition and see the extent to which they can be supported both theoretically and empirically. -

Seminar on Theories of the State

SOCIOLOGY 924 SEMINAR ON THEORIES OF THE STATE Fall Semester, 2002 Professor Erik Olin Wright Department of Sociology University of Wisconsin Madison, Wisconsin Wednesdays, 6:00-8:30, room 8108 Social Science This seminar has two primary objectives: First, to deepen students’ understanding of alternative theoretical approaches to studying the state and politics, and second, to examine a range of interesting empirical/historical studies that embody, in different ways, these approaches in order to gain a better understanding of the relationship between abstract theoretical ideas and concrete empirical investigation. We will focus on three broad theoretical approaches: 1. Marxist or class-analytic approaches which anchor the analysis of the state in terms of its structural relationship to capitalism as a system of class relations. 2. Weberian or organization-analytic approaches which emphasize the ways in which states constitute autonomous sources of power and operate on the basis of institutional logics and dynamics with variable forms of interaction with other sources of power in society. 3. Microfoundational approaches which emphasize the ways in which the actions of states are rooted in the interests, motivations, and strategic dilemmas of the people who occupy positions in the state. While these three approaches have long pedigrees, we will not explore the classical formulations or the historical development of these traditions of analysis, but rather will focus on the most developed versions of each approach. Also, while these approaches are often posed as rivals, in fact much contemporary work combines them in various ways. One of the tasks of the seminar is to examine the ways in which these different traditions of theoretical work complement rather than contradict each other in generating compelling explanations of concrete historical problems of understanding states and politics. -

1 Book Review Leo Panitch, Greg Albo and Vivek Chibber, Eds. the Socialist Register 2014, Registering Class New York, NY: Monthl

The Innovation Journal: The Public Sector Innovation Journal, Volume 19(2), 2014, article 10. Book Review Leo Panitch, Greg Albo and Vivek Chibber, eds. The Socialist Register 2014, Registering Class New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 2014 Reviewed by Howard A. Doughty It seems that, despite the disrepute that Marxism has endured since the implosion of the Soviet Union, the old fellow may have gotten a few more things right than is commonly accepted within briefly triumphant neoliberal circles. These circles have pretty much defined the dominant ideological perspective among Western liberal democracies and also in those developing nations, especially on the Pacific Rim, that have displayed remarkable economic growth over the past few decades. Mainly stuck away in small fissures in the solid rocks of the North American academy and in the geological crannies and nooks of European intellectual formations, Marxist theory and scholarship is fairly safely contained. It barely intrudes into the world of corporate think-tanks, financial media and the policy development stratagems of mainstream political parties. In fact, it seems no longer to be very interesting to agents of the national security state who are apparently more preoccupied with Islamic jihads, Ukrainian separatists and opportunities for covert actions and regime changes elsewhere. That said, initially in the land where “the Moor” spent his most fruitful years in the British Museum, and now at York University in Canada, one of the most durable intellectual journals devoted to leftist perspectives on events continues to offer refreshing analyses and criticisms of late capitalist political economy. I speak, of course, of The Socialist Register. -

Critical Companion to Contemporary Marxism

Critical Companion to Contemporary Marxism BIDET2_f1_i-xv.indd i 10/25/2007 8:05:05 PM Historical Materialism Book Series Editorial Board Paul Blackledge, Leeds – Sébastien Budgen, Paris Michael Krätke, Amsterdam – Stathis Kouvelakis, London – Marcel van der Linden, Amsterdam China Miéville, London – Paul Reynolds, Lancashire Peter Thomas, Amsterdam VOLUME 16 BIDET2_f1_i-xv.indd ii 10/25/2007 8:05:05 PM Critical Companion to Contemporary Marxism Edited by Jacques Bidet and Stathis Kouvelakis LEIDEN • BOSTON 2008 BIDET2_f1_i-xv.indd iii 10/25/2007 8:05:05 PM This book is an English translation of Jacques Bidet and Eustache Kouvelakis, Dic- tionnaire Marx contemporain. C. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 2001. Ouvrage publié avec le concours du Ministère français chargé de la culture – Centre national du Livre. This book has been published with financial aid of CNL (Centre National du Livre), France. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Translations by Gregory Elliott. ISSN 1570-1522 ISBN 978 90 04 14598 6 Copyright 2008 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Capitalism, Laws of Motion and Social Relations of Production

Historical Materialism 21.4 (2013) 71–91 brill.com/hima Capitalism, Laws of Motion and Social Relations of Production Charles Post Borough of Manhattan Community College-City University of New York [email protected] Abstract Theory as History brings together twelve essays by Jarius Banaji addressing the nature of modes of production, the forms of historical capitalism and the varieties of pre-capitalist modes of production. Problematic formulations concerning the relationship of social-property relations and the laws of motion of different modes of production and his notion of merchant and slave- holding capitalism undermines Banaji’s project of constructing a non-unilinear, non-Eurocentric Marxism. Keywords modes of production, social-property relations, origins of capitalism, historical capitalism, plantation slavery, merchant capitalism Over the past four decades, Jairus Banaji has contributed to the revival of a non-dogmatic, anti-Stalinist Marxism. His theoretical and empirical research ranges over a breathtaking array of topics – the long and complex evolution of social relations of production in Europe from the fall of the Roman Empire to the consolidation of feudalism, the dynamics of rural social structures in South Asia over the past two centuries, value and crisis theory, and the development of labour organisation and struggle in transnational corporations.1 Banaji has also made classical Marxist texts, including segments of Kautsky’s The Agrarian Question2 and Grossman’s The Law of Accumulation,3 available to English-speaking audiences. In all of his work, Banaji consistently challenges The author would like to thank Robert Brenner, Liam Campling, Vivek Chibber, David McNally, Teresa Stern and Ellen Meiksins-Wood for their comments and suggestions on an earlier version of this essay. -

S O C I a L I S T R E G I S T E R 2 0

SOCIALI S T REGI S TE R 2009 THE SOCIALIST REGISTER Founded in 1964 EDITORS LEO PANITCH COLIN LEYS FOUNDING EDITORS RALPH MILIBAND (1924-1994) JOHN SAVILLE ASSOCIATE EDITORS GREGORY ALBO VIVEK CHIBBER ALFREDO SAAD-FILHO CONTRIBUTING EDITORS HENRY BERNSTEIN HUW BEYNON VARDA BURSTYN PAUL CAMMACK DAVID COATES GEORGE COMNINEL TERRY EAGLETON BARBARA EPSTEIN BILL FLETCHER JR SAM GINDIN BARBARA HARRISS-WHITE JUDITH ADLER HELLMAN URSULA HUWS STEVE JEFFERYS SHEILA ROWBOTHAM JOHN S. SAUL HILARY WAINWRIGHT ELLEN MEIKSINS WOOD ALAN ZUEGE CORRESPONDING EDITORS: AIJAZ AHMAD, NEW DELHI ELMAR ALTVATER, BERLIN PATRICK BOND, DURBAN ATILIO BORON, BUENOS AIRES HIDAYAT (GERARD) GREENFIELD, JAKARTA MICHAEL LOWY, PARIS MICHAEL SPOURDALAKIS, ATHENS Visit our website at: http://www.socialistregister.com for a detailed list of all our issues, order forms and an online selection of past prefaces and essays, and to find out how to join our listserv. .. SOCIALI S T REGI S TE R 2009 VIOLENCE TODAY Actually-Existing Barbarism Edited by LEO PANITCH and COLIN LEYS THE MERLIN PRESS, LONDON MONTHLY REVIEW PRESS, NEW YORK FERNWOOD PUBLISHING, HALIFAX First published in 2008 by The Merlin Press Ltd. 6 Crane Street Chambers Crane Street Pontypool NP4 6ND Wales www.merlinpress.co.uk © The Merlin Press, 2008 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Socialist register 2009 : violence today : actually existing barbarism /edited by Leo Panitch and Colin Leys. 1. Violence. 2. Imperialism. 3. Capitalism. I. Panitch, Leo, 1945- II. Leys, Colin, 1931- III. Title:Violence today. HM886.S62 2008 303.6 C2008-903393-0 ISSN. -

On the Articulation of Marxist and Non-Marxist Theory in Colonial Historiography

On the articulation of Marxist and non-Marxist theory in Colonial Historiography. Vivek Chibber’s Postcolonial Theory and the Spectre of Capital George Steinmetz Forthcoming in Journal of World System Research (2014) Postcolonial Theory and the Spectre of Capital is an important book on a topic of major importance for all of the human and social sciences. The book’s implications reach far beyond Chibber’s critique of subaltern studies, which is his most obvious focus. Chibber’s overarching argument is twofold: capitalism does universalize itself to the colonial and postcolonial world, but at the same time, capitalism does not permeate or encompass all other aspects of social practice. As it stands, this is already an important argument for social theory generally and not just for analysts working on former colonies like India. The crisis of what used to be called western Marxism led to two main responses among Marxists. While many simply abandoned Marxism, becoming “post-Marxist,”1 others became “neo-orthodox,” refusing to acknowledge the autonomy of any social practices from capitalism.2 Chibber’s position is closer to the more nuanced positions of the “regulationist” school3; it is also compatible with a neo-historicist critical realism4 that combines an ontology of emergent causal powers with an anti-essentialist epistemology according to which historically varying conjunctures of causal mechanisms interact in contingent, often unpredictable ways to produce empirical events. The fact that Chibber’s book’s packaging suggests an all-out assault on anyone who would dare to deviate Marxist orthodoxy does not square with the actual content of the book. -

The Abcs of Socialism

The ABCs of Socialism The ABCs of Socialism was produced as a collaboration between Verso Books and Jacobin magazine, which is released online and quarterly in print to over 15,000 subscribers. If you’re interested in the ideas in this book, join a Jacobin reading group in over seventy cities across the world. Visit www.jacobinmag.com/reading-groups/ for more details. The ABCs of Socialism EDITED BY Bhaskar Sunkara ILLUSTRATED BY Phil Wrigglesworth First published by Verso 2016 © Jacobin Foundation Ltd. All rights reserved The moral rights of the authors have been asserted Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-726-4 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Typeset in Antwerp by A2-Type Printed in the US by Sheridan Press Among hundreds of others, this book was made possible by the generosity of: Saki Bailey Danny Bates John Erganian Marshall Mayer David Mehan Mark Ó Dochartaigh Brian Skiffington Frederick Sperounis Francis Tseng Nathan Zimmerman Special thanks to the Anita L. Mishler Education Fund ([email protected]) Date • Jacobin • This book contains in-text annotations for further reading. Some annotations Article Title Author contain hyperlink information for direct 12345 reference to articles in Jacobin’s online archive. Simply copy the digits included in the annotation to the end of the following URL for related articles: www.jacobinmag.com/?p=12345 About the Authors Nicole Aschoff is the managing editor at Jacobin and the author of The New Prophets of Capital. -

The Dual Legacy of Orientalism

The Dual Legacy of Orientalism Vivek Chibber Sociology Department New York University Forthcoming in Bashir Abu-Manneh ed. Edward Said, (Cambridge University Press, 2018). 1 2 Introduction There is little doubt that Edward Said’s Orientalism is one of the most influential scholarly works of the past few decades. While it was initially presented by its author as a study of how a particular body of knowledge contributed to the spread of European colonial rule, its influence has extended to just about every domain connected with imperialism, colonial history, race, and political identity. Owing to the very scope of the work that either builds directly on Said’s argument, or is inspired by it, it is not a simple task to assess his legacy. Perhaps the most contentious issue is its impact on the study of the Global South and more specifically, on the field that developed rapidly after Orientalism’s publication, post-colonial studies. In many ways, it is hard to imagine that there could be a direct connection between Said’s profound commitment to humanism, universal rights, secularism and liberalism on the one hand, and postcolonial theory’s quite explicit disavowal of, or at least its skepticism toward, those very tropes. And indeed, his most able interpreters have made a powerful case that the connection is, at best, tenuous. In this essay I will suggest that whatever his own commitments, Orientalism prefigured, and hence encouraged, some of the central dogmas of postcolonial studies – indeed, the very ones that cannot withstand scrutiny. And in spite of its very many strengths, its legacy is therefore a dual one – propelling the critique of imperialism into the very heart of the mainstream on the one hand, but also giving strength to intellectual fashions that have undermined the possibility of that very critique.