Capitalism, Laws of Motion and Social Relations of Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samir Gandesha1 the Aesthetic Politics of Hegemony

Studi di estetica, anno XLVI, IV serie, 3/2018 ISSN 0585-4733, ISSN digitale 1825-8646, DOI 10.7413/18258646066 Samir Gandesha1 The aesthetic politics of hegemony Abstract In this article, it is argued that Gramsci’s conception of hegemony ought to be located not simply in the theory and praxis of Leninism but also in Gramsci’s read- ing of Machiavelli. By situating such a reading in relation to Nietzsche’s notion of will to power, it is possible to defend Gramsci’s political theory against some of the criticisms leveled by those who decry the “hegemony of hegemony”. Such a reading of the concept of hegemony enables us to understand the idea of “com- mon sense” as oriented towards the distribution and redistribution of the sensible. Keywords Aesthetics, Gramsci, Hegemony 1. Introduction In the introduction to our book Aesthetic Marx (2017), Johan Hartle and I point out that there is one main problem with the Marxological approach to the aesthetic dimensions of Marx’s writings: the classical understanding of the discipline of aesthetics that is presupposed by such exegetical approaches must also be interrogated. “Aesthetics” is normally understood as a philosophical discipline that concerns the conditions for the possibility of judgments of taste, as a specific ra- tionality that maintains its own autonomy, its own purposeless pur- posiveness, against contending and competing the spheres of value (the epistemic, the moral), and that deals with normative criteria in order to evaluate forms of experience and artistic developments on 1 [email protected]. I would like to thank professor Stefano Marino for his extremely helpful suggestions and assistance with this article. -

Marxist Economics: How Capitalism Works, and How It Doesn't

MARXIST ECONOMICS: HOW CAPITALISM WORKS, ANO HOW IT DOESN'T 49 Another reason, however, was that he wanted to show how the appear- ance of "equal exchange" of commodities in the market camouflaged ~ , inequality and exploitation. At its most superficial level, capitalism can ' V be described as a system in which production of commodities for the market becomes the dominant form. The problem for most economic analyses is that they don't get beyond th?s level. C~apter Four Commodities, Marx argued, have a dual character, having both "use value" and "exchange value." Like all products of human labor, they have Marxist Economics: use values, that is, they possess some useful quality for the individual or society in question. The commodity could be something that could be directly consumed, like food, or it could be a tool, like a spear or a ham How Capitalism Works, mer. A commodity must be useful to some potential buyer-it must have use value-or it cannot be sold. Yet it also has an exchange value, that is, and How It Doesn't it can exchange for other commodities in particular proportions. Com modities, however, are clearly not exchanged according to their degree of usefulness. On a scale of survival, food is more important than cars, but or most people, economics is a mystery better left unsolved. Econo that's not how their relative prices are set. Nor is weight a measure. I can't mists are viewed alternatively as geniuses or snake oil salesmen. exchange a pound of wheat for a pound of silver. -

1- TECHNOLOGY Q L M. Muniagurria Econ 464 Microeconomics Handout

M. Muniagurria Econ 464 Microeconomics Handout (Part 1) I. TECHNOLOGY : Production Function, Marginal Productivity of Inputs, Isoquants (1) Case of One Input: L (Labor): q = f (L) • Let q equal output so the production function relates L to q. (How much output can be produced with a given amount of labor?) • Marginal productivity of labor = MPL is defined as q = Slope of prod. Function L Small changes i.e. The change in output if we change the amount of labor used by a very small amount. • How to find total output (q) if we only have information about the MPL: “In general” q is equal to the area under the MPL curve when there is only one input. Examples: (a) Linear production functions. Possible forms: q = 10 L| MPL = 10 q = ½ L| MPL = ½ q = 4 L| MPL = 4 The production function q = 4L is graphed below. -1- Notice that if we only have diagram 2, we can calculate output for different amounts of labor as the area under MPL: If L = 2 | q = Area below MPL for L Less or equal to 2 = = in Diagram 2 8 Remark: In all the examples in (a) MPL is constant. (b) Production Functions With Decreasing MPL. Remark: Often this is thought as the case of one variable input (Labor = L) and a fixed factor (land or entrepreneurial ability) (2) Case of Two Variable Inputs: q = f (L, K) L (Labor), K (Capital) • Production function relates L & K to q (total output) • Isoquant: Combinations of L & K that can achieve the same q -2- • Marginal Productivities )q MPL ' Small changes )L K constant )q MPK ' Small changes )K L constant )K • MRTS = - Slope of Isoquant = Absolute value of Along Isoquant )L Examples (a) Linear (L & K are perfect substitutes) Possible forms: q = 10 L + 5 K Y MPL = 10 MPK = 5 q = L + K Y MPL = 1 MPK = 1 q = 2L + K Y MPL = 2 MPK = 1 • The production function q = 2 L + K is graphed below. -

Dangers of Deflation Douglas H

ERD POLICY BRIEF SERIES Economics and Research Department Number 12 Dangers of Deflation Douglas H. Brooks Pilipinas F. Quising Asian Development Bank http://www.adb.org Asian Development Bank P.O. Box 789 0980 Manila Philippines 2002 by Asian Development Bank December 2002 ISSN 1655-5260 The views expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Asian Development Bank. The ERD Policy Brief Series is based on papers or notes prepared by ADB staff and their resource persons. The series is designed to provide concise nontechnical accounts of policy issues of topical interest to ADB management, Board of Directors, and staff. Though prepared primarily for internal readership within the ADB, the series may be accessed by interested external readers. Feedback is welcome via e-mail ([email protected]). ERD POLICY BRIEF NO. 12 Dangers of Deflation Douglas H. Brooks and Pilipinas F. Quising December 2002 ecently, there has been growing concern about deflation in some Rcountries and the possibility of deflation at the global level. Aggregate demand, output, and employment could stagnate or decline, particularly where debt levels are already high. Standard economic policy stimuli could become less effective, while few policymakers have experience in preventing or halting deflation with alternative means. Causes and Consequences of Deflation Deflation refers to a fall in prices, leading to a negative change in the price index over a sustained period. The fall in prices can result from improvements in productivity, advances in technology, changes in the policy environment (e.g., deregulation), a drop in prices of major inputs (e.g., oil), excess capacity, or weak demand. -

Economics 352: Intermediate Microeconomics

EC 352: Intermediate Microeconomics, Lecture 7 Economics 352: Intermediate Microeconomics Notes and Sample Questions Chapter 7: Production Functions This chapter will introduce the idea of a production function. A production process uses inputs such as labor, energy, raw materials and capital to produce one (or more) outputs, which may be computer software, steel, massages or anything else that can be sold. A production function is a mathematical relationship between the quantities of inputs used and the maximum quantity of output that can be produced with those quantities of inputs. For example, if the inputs are labor and capital (l and k, respectively), the maximum quantity of output that may be produced is given by: q = f(k, l) Marginal physical product The marginal physical product of a production function is the increase in output resulting from a small increase in one of the inputs, holding other inputs constant. In terms of the math, this is the partial derivative of the production function with respect to that particular input. The marginal product of capital and the marginal product of labor are: ∂q MP = = f k ∂k k ∂q MP = = f l ∂l l The usual assumption is that marginal (physical) product of an input decreases as the quantity of that input increases. This characteristic is called diminishing marginal product. For example, given a certain amount of machinery in a factory, more and more labor may be added, but as more labor is added, at some point the marginal product of labor, or the extra output gained from adding one more worker, will begin to decline. -

Modern Intellectual History

0RGHUQ,QWHOOHFWXDO+LVWRU\ KWWSMRXUQDOVFDPEULGJHRUJ0,+ $GGLWLRQDOVHUYLFHVIRU0RGHUQ,QWHOOHFWXDO+LVWRU\ (PDLODOHUWV&OLFNKHUH 6XEVFULSWLRQV&OLFNKHUH &RPPHUFLDOUHSULQWV&OLFNKHUH 7HUPVRIXVH&OLFNKHUH 7+($&&,'(17$/0$5;,67$1'5(*81'(5)5$1.$1'7+( ³1(20$5;,67´7+(25<2)81'(5'(9(/230(17± &2'<67(3+(16 0RGHUQ,QWHOOHFWXDO+LVWRU\)LUVW9LHZ$UWLFOH$SULOSS '2,63XEOLVKHGRQOLQH$SULO /LQNWRWKLVDUWLFOHKWWSMRXUQDOVFDPEULGJHRUJDEVWUDFWB6 +RZWRFLWHWKLVDUWLFOH &2'<67(3+(167+($&&,'(17$/0$5;,67$1'5(*81'(5)5$1.$1' 7+(³1(20$5;,67´7+(25<2)81'(5'(9(/230(17± 0RGHUQ,QWHOOHFWXDO+LVWRU\$YDLODEOHRQ&-2GRL 6 5HTXHVW3HUPLVVLRQV&OLFNKHUH 'RZQORDGHGIURPKWWSMRXUQDOVFDPEULGJHRUJ0,+,3DGGUHVVRQ0D\ Modern Intellectual History,page1 of 32 C Cambridge University Press 2016 ! doi:10.1017/S1479244316000123 the accidental marxist: andre gunder frank and the “neo-marxist” theory of underdevelopment, 1958–1967 cody stephens Department of History, University of California–Santa Barbara E-mail: [email protected] Based on newly available archival records, this article examines the life and thought of Andre Gunder Frank from his years as a graduate student in development economics to the publication of his first and most influential book. A closer look at the evolution of Frank’s thought provides new insight into the relationship of his brand of “neo-Marxist” development theories with both classical Marxism and modernization theory. Frank interpreted Marxist political debates according to the categories of thought of 1950s American development economics, and in doing so he both misinterpreted fundamental aspects of Marxism and simultaneously generated lively theoretical debates that remain relevant today. Paul Sweezy thought Andre Gunder Frank’s Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America (hereafter CU)wouldbeabighit.AstheheadofMonthlyReview Press, a small but important publishing operation held together largely by his own efforts, Sweezy had to choose carefully the projects on which he would expend his and his small staff’s limited time and energy. -

The Politics of Market Reform Altering State Development Policy in Southern Africa

ASPJ Africa & Francophonie - 3rd Quarter 2013 The Politics of Market Reform Altering State Development Policy in Southern Africa SHAUKAT ANSARI* Introduction outh Africa’s transition from a racially exclusive apartheid state to a liberal democracy—referred to as a “double transition” to denote the economic dynamics behind the political transformation—has attracted the attention of a substantial number of researchers from a variety of disciplines.1 The topic of radical transformation in the African NationalS Congress’s (ANC) official position on state developmental policy has aroused perhaps the greatest interest among scholars. Prior to 1994, few observers would have predicted that the white minority in South Africa would relinquish its formal rule predicated on racial domination while avoiding the initiation of structural transformations involving a fundamen- tal reorientation of existing social relations. Yet, the end of apartheid and the liberation movement’s victory did not result in the transformation of capitalist social-property relations. In fact, upon taking power, the ANC implemented a homegrown, neoliberal structural adjustment program that opened South Africa to foreign economic interests and propelled the coun- try down a path of market liberalization. Explanations offered by scholars to account for this policy shift within the ANC can be roughly divided into two competing models. According to the first one, the South African government’s ability to maneuver was se- verely restricted by structural constraints imposed by international and domestic business interests in a post–Cold War environment. The fact that *The author is a doctoral candidate at the University of Toronto in the Department of Political Science. -

Slavery, Capitalism, and the “Proletariat”

1 1 The Slave-Machine: Slavery, Capital- ism, and the “Proletariat” in The Black Jacobins and Capital Nick Nesbitt This essay argues that C. L. R. James’s Marxist humanism is inherently inade- quate for describing the distinction and transition between slavery and capitalism. To do so, the essay interrogates James’s famous claim in The Black Jacobins (1938) that the slaves of St. Domingue were “closer to a modern proletariat than any group of workers in existence at the time,” by comparing James’s understand- ing of the concept of proletariat—there and in World Revolution (1937)—with Marx’s various developments of the concept across the three volumes of Capital. This analysis distinguishes James’s political and historicist deployment of the term from Marx’s analytical usage of the notion in his categorial critique of capitalism.In contrast with James’s linear, Marxist-humanist understanding of the passage from slavery to capitalism, Marx himself demarcates a well-defined delineation between these two basic categories, understood in Capital as analytically (as opposed to historically) distinct modes of production.The essay thus concludes by analyzing Marx’s conceptual differentiation of slavery and industrial capitalism in Capital, drawing on Etienne Balibar’s analysis of the concepts of mode of production and transition in Reading Capital (1965). The slaves worked on the land, and, like revolutionary peasants everywhere, they aimed at the extermination of their oppressors. But working and living together in gangs of hundreds on the huge sugar-factories which covered the North Plain, they were closer to a modern proletariat than any group of workers in existence at the time, and the rising was, therefore, a thoroughly prepared and organized mass movement. -

Fall 2005 Newsletter of the ASA Comparative and Historical Sociology Section Volume 17, No

________________________________________________________________________ __ Comparative & Historical Sociology Fall 2005 Newsletter of the ASA Comparative and Historical Sociology section Volume 17, No. 1 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ From the Chair: State of the CHS Union SECTION OFFICERS 2005-2006 Richard Lachmann SUNY-Albany Chair Richard Lachmann Columns of this sort are the academic equivalents of State SUNY-Albany of the Union speeches, opportunities to say that all is well and to take credit for the good times. Chair-Elect William Roy I can’t (and won’t) take credit for the healthy state of com- University of California-Los Angeles parative historical sociology but I do want to encourage all of us to recognize the richness of our theoretical discus- sions and the breadth and depth of our empirical work. The Past Chair Jeff Goodwin mid-twentieth century revolution in historiography—the New York University discovery and creative interpretation of previously ignored sources, many created by historical actors whose agency had been slighted and misunderstood—has been succeeded Secretary-Treasurer by the recent flowering of comparative historical work by Genevieve Zubrzycki sociologists. University of Michigan We can see the ambition and reach of our colleagues’ work Council Members in the research presented at our section’s panels in Phila- Miguel A. Centeno, Princeton (2007) delphia and in the plans for sessions next year (see the call Rebecca Jean Emigh, UCLA (2006) for papers elsewhere in this newsletter). The Author Meets Marion Fourade-Gourinchas, Berkeley (2008) Critics panel on Julia Adams, Lis Clemens, and Ann Or- Fatma Muge Gocek, U Michigan (2006) Mara Loveman, UW-Madison (2008) loff’s Remaking Modernity: Politics, History, and Sociol- James Mahoney, Northwestern (2007) ogy was emblematic of how our field’s progress got ex- pressed at the Annual Meeting. -

1 Introduction: Why Geopolitical Economy?

1 INTRODUCTION: WHY GEOPOLITICAL ECONOMY? The owl of Minerva, Hegel once remarked, takes wing at dusk. Knowledge results from reflection after the tumult of the day. This gloomy view may be too sweeping, but it certainly applies to the multipolar world order. Influential figures began hailing it in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession. The American president of the World Bank spoke of ‘a new, fast-evolving multi-polar world economy’ (World Bank, 2010). Veteran international financier George Soros predicted that ‘the current financial crisis is less likely to cause a global recession than a radical realignment of the global economy, with a relative decline of the US and the rise of China and other countries in the developing world’ (2008). However, the multipolar world order was much longer in the making. Developments of this magnitude simply don’t happen overnight even in a crisis (though, as we shall see, emerging multipolarity was a decisive factor in causing it), and this has important implications for prevailing understandings of the capitalist world order. Recent accounts stressed its economic unity: globalization conceived a world unified by markets alone while empire proposed one unified by the world’s most powerful – ‘hegemonic’ or ‘imperial’ (the terms tended to be used interchangeably) – state. They also assumed either that nation-states were not relevant to explaining the world order (globalization), or that only one, the United States, was (empire). We can call these views cosmopolitan, a term the Oxford English Dictionary defines as ‘not restricted to any one country or its inhabitants’ and ‘free from national limitations or attachments’. -

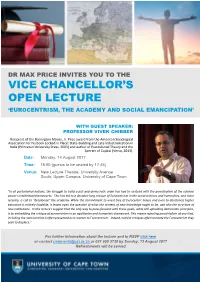

Vice Chancellor's Open Lecture

DR MAX PRICE INVITES YOU TO THE VICE CHANCELLOR’S OPEN LECTURE ‘EUROCENTRISM, THE ACADEMY AND SOCIAL EMANCIPATION’ WITH GUEST SPEAKER: PROFESSOR VIVEK CHIBBER Recipient of the Barrington Moore, Jr. Prize award from the American Sociological Association for his book Locked in Place: State-Building and Late Industrialization in India (Princeton University Press, 2003) and author of Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital (Verso, 2013). Date: Monday, 14 August 2017 Time: 18:00 (guests to be seated by 17:45) Venue: New Lecture Theatre, University Avenue South, Upper Campus, University of Cape Town "In all postcolonial nations, the struggle to build a just and democratic order has had to contend with the parochialism of the colonial power’s intellectual frameworks. This has led to a decades-long critique of Eurocentrism in the social sciences and humanities, and more recently, a call to “decolonize” the academy. While the commitment to wrest free of Eurocentric biases and even to decolonize higher education is entirely laudable, it leaves open the question of what the content of new knowledge ought to be, and also the structure of new institutions. In this lecture I suggest that the only way to press forward with these goals, while still upholding democratic principles, is by embedding the critique of eurocentrism in an egalitarian and humanistic framework. This means rejecting parochialism of any kind, including the nativism that is often presented as a counter to Eurocentrism. Indeed, nativist critiques often recreate the Eurocentrism they seek to displace." For further information about the lecture and to RSVP click here or contact [email protected] or 021 650 3730 by Sunday, 13 August 2017 Refreshments will be served . -

The Survival of Capitalism: Reproduction of the Relations Of

THE SURVIVAL OF CAPITALISM Henri Lefebvre THE SURVIVAL OF CAPITALISM Reproduction of the Relations of Production Translated by Frank Bryant St. Martin's Press, New York. Copyright © 1973 by Editions Anthropos Translation copyright © 1976 by Allison & Busby All rights reserved. For information, write: StMartin's Press. Inc.• 175 Fifth Avenue. New York. N.Y. 10010 Printed in Great Britain Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 75-32932 First published in the United States of America in 1976 AFFILIATED PUBLISHERS: Macmillan Limited. London also at Bombay. Calcutta, Madras and Melbourne CONTENTS 1. The discovery 7 2. Reproduction of the relations of production 42 3. Is the working class revolutionary? 92 4. Ideologies of growth 102 5. Alternatives 120 Index 128 1 THE DISCOVERY I The reproduction of the relations of production, both as a con cept and as a reality, has not been "discovered": it has revealed itself. Neither the adventurer in knowledge nor the mere recorder of facts can sight this "continent" before actually exploring it. If it exists, it rose from the waves like a reef, together with the ocean itself and the spray. The metaphor "continent" stands for capitalism as a mode of production, a totality which has never been systematised or achieved, is never "over and done with", and is still being realised. It has taken a considerable period of work to say exactly what it is that is revealing itself. Before the question could be accurately formulated a whole constellation of concepts had to be elaborated through a series of approximations: "the everyday", "the urban", "the repetitive" and "the differential"; "strategies".