Fall 2005 Newsletter of the ASA Comparative and Historical Sociology Section Volume 17, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samir Gandesha1 the Aesthetic Politics of Hegemony

Studi di estetica, anno XLVI, IV serie, 3/2018 ISSN 0585-4733, ISSN digitale 1825-8646, DOI 10.7413/18258646066 Samir Gandesha1 The aesthetic politics of hegemony Abstract In this article, it is argued that Gramsci’s conception of hegemony ought to be located not simply in the theory and praxis of Leninism but also in Gramsci’s read- ing of Machiavelli. By situating such a reading in relation to Nietzsche’s notion of will to power, it is possible to defend Gramsci’s political theory against some of the criticisms leveled by those who decry the “hegemony of hegemony”. Such a reading of the concept of hegemony enables us to understand the idea of “com- mon sense” as oriented towards the distribution and redistribution of the sensible. Keywords Aesthetics, Gramsci, Hegemony 1. Introduction In the introduction to our book Aesthetic Marx (2017), Johan Hartle and I point out that there is one main problem with the Marxological approach to the aesthetic dimensions of Marx’s writings: the classical understanding of the discipline of aesthetics that is presupposed by such exegetical approaches must also be interrogated. “Aesthetics” is normally understood as a philosophical discipline that concerns the conditions for the possibility of judgments of taste, as a specific ra- tionality that maintains its own autonomy, its own purposeless pur- posiveness, against contending and competing the spheres of value (the epistemic, the moral), and that deals with normative criteria in order to evaluate forms of experience and artistic developments on 1 [email protected]. I would like to thank professor Stefano Marino for his extremely helpful suggestions and assistance with this article. -

Curriculum Vitae Sourabh Singh Last Revised: November 09, 2020

Curriculum Vitae Sourabh Singh Last Revised: November 09, 2020 General Information University address: Sociology College of Social Sciences & Public Policy Bellamy Building 0526 Florida State University Tallahassee, Florida 32306-2270 E-mail address: [email protected] Professional Preparation 2014 Ph.D, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Major: Sociology. Political Sociology, Sociological Theories, Comparative Historical Sociology, Network Analysis. Supervisor: Paul McLean. 2001 MA, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Major: Sociology. 1998 B.Sc, Atma Ram Sanatan Dharm College, Delhi University, New Delhi. Major: Physics (Honors). Research and Teaching Interests Comparative and Historical Sociology Political Sociology Sociological Theory Culture Professional Experience 2018–present Assistant Professor, SOCIOLOGY, Florida State University. 2018–present Teaching Faculty I Adjunct, SOCIOLOGY, Florida State University. Current Membership in Professional Organizations American Sociological Association Social Science History Association Publications Published Articles Singh, S. (2020). Rethinking Political Elites' Mass-Linkage Strategies: Lessons from the Study of Indira Gandhi's Political Habitus. Journal of Historical Sociology. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/johs.12291 doi:10.1111/johs.12291 Singh, S. (2020). To Rely or Not to Rely on Common Sense? Introducing Critical Realism's Insights to Social Network Analysis. Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior, 50(2), 203-222. Singh, S. (2019). How Should we Study Relational Structure? Critically Comparing Epistemological Position of Social Network Analysis and Field Theory. Sociology, 53(4), 762-778. Singh, S. (2019). Science, Common Sense and Sociological Analysis: A Critical Appreciation of the Epistemological Foundation of Field Theory. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 49(2), 87-107. Singh, S. (2018). Anchoring Depth Ontology to Epistemological Strategies of Field Theory: Exploring the Possibility of Developing a Core for Sociological Analysis. -

Theory and Method in Historical Sociology Soc 6401H

THEORY AND METHOD IN HISTORICAL SOCIOLOGY SOC 6401H Instructor: Joseph M. Bryant Time: Thursdays, 4-6, Room 240 Email: [email protected] Office: Department of Sociology, 725 Spadina, Rm. 346 Phone: 946-5901 We know only a single science, the science of history. One can look at history from two sides and divide it into the history of nature and the history of men. The two sides are, however, inseparable; the history of nature and the history of men are dependent on each other so long as men exist. Marx & Engels (1845) Every social science—or better, every well-considered social study—requires an historical scope of conception and a full use of historical materials. C. Wright Mills (1959) SYNOPSIS: Can the major constraining dichotomies and polarities that have skewed the history of the social sciences over the past two centuries—voluntarism/determinism, agency/structure, nominalism/realism, micro/macro, objectivism/subjectivism, nomothetic/idiographic, maximizing rationality/cultural specificity—be resolved and transcended through use of a contextual-sequential logic of explanation, as offered in Historical Sociology? In an effort to answer that question, we will examine the central ontological and epistemological issues and controversies raised by recent efforts to develop a fully historical social science, a fully sociological historiography. We will open with a review of the celebrated Methodenstreite that shaped the formation of the social science disciplines in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—disputes that turned heavily on disagreements regarding the proper relationship between historical inquiry and sociological theorizing. The program of positivism—to model social science after the nomological natural sciences—gained institutional ascendancy, and history was driven to an “external” and largely “auxiliary” status within disciplines such as sociology and economics. -

Historical Sociology in International Relations: Open Society, Research Programme and Vocation

George Lawson Historical sociology in international relations: open society, research programme and vocation Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Lawson, George (2007) Historical sociology in international relations: open society, research programme and vocation. International politics, 44 (4). pp. 343-368. DOI: 10.1057/palgrave.ip.8800195 © 2007 Palgrave Macmillan This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/2742/ Available in LSE Research Online: August 2012 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript accepted version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the published version may remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Historical Sociology in International Relations: Open Society, Research Programme and Vocation Article for International Politics forum on Historical Sociology April 2006 Abstract Over the last twenty years, historical sociology has become an increasingly conspicuous part of the broader field of International Relations (IR) theory, with advocates making a series of interventions in subjects as diverse as the origins and varieties of international systems over time and place, to work on the co-constitutive relationship between the international realm and state-society relations in processes of radical change. -

Historical Sociology Vs. History

Julia Adams. The Familial State: Ruling Families and Merchant Capitalism in Early Modern Europe. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005. xi + 235 pp. $35.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-8014-3308-5. Reviewed by Susan R. Boettcher Published on H-Low-Countries (November, 2007) Historical Sociology vs. History discipline, gender relations) developed by practi‐ Two fundamental concerns of historical soci‐ tioners of the "new cultural history."[2] In her ology have always been the origin and nature of new book on the relationship of gender to devel‐ modernity. In response to modernization and de‐ oping states, Adams claims to be "charting ... new pendency theory, which seemed to present territory in the study of the formation of Euro‐ modernity as an objectively describable condi‐ pean states" (p. 12). However, while Adams adds tion, previous generations of historical sociolo‐ some elements to her account, especially gender gists studied comparative issues in early modern and the colonial economy, if this work is indica‐ European history, especially themes emphasized tive of the "new" historical sociology, it provides in that body of theory, such as democratic revolu‐ us primarily with another version of the story tion and the emergence of the nation-state. Those rather than new questions, different approaches, sociologists (one thinks of Charles Tilly, Theda or perhaps most importantly, new characteriza‐ Skocpol, Barrington Moore, and Immanuel tions of the genesis and trajectory of the early Wallerstein) enriched not only the questions his‐ modern state. torians asked but substantially influenced the so‐ Adams's book is organized in an introduction cial history written in response. -

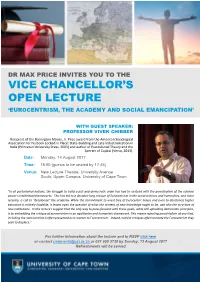

Vice Chancellor's Open Lecture

DR MAX PRICE INVITES YOU TO THE VICE CHANCELLOR’S OPEN LECTURE ‘EUROCENTRISM, THE ACADEMY AND SOCIAL EMANCIPATION’ WITH GUEST SPEAKER: PROFESSOR VIVEK CHIBBER Recipient of the Barrington Moore, Jr. Prize award from the American Sociological Association for his book Locked in Place: State-Building and Late Industrialization in India (Princeton University Press, 2003) and author of Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital (Verso, 2013). Date: Monday, 14 August 2017 Time: 18:00 (guests to be seated by 17:45) Venue: New Lecture Theatre, University Avenue South, Upper Campus, University of Cape Town "In all postcolonial nations, the struggle to build a just and democratic order has had to contend with the parochialism of the colonial power’s intellectual frameworks. This has led to a decades-long critique of Eurocentrism in the social sciences and humanities, and more recently, a call to “decolonize” the academy. While the commitment to wrest free of Eurocentric biases and even to decolonize higher education is entirely laudable, it leaves open the question of what the content of new knowledge ought to be, and also the structure of new institutions. In this lecture I suggest that the only way to press forward with these goals, while still upholding democratic principles, is by embedding the critique of eurocentrism in an egalitarian and humanistic framework. This means rejecting parochialism of any kind, including the nativism that is often presented as a counter to Eurocentrism. Indeed, nativist critiques often recreate the Eurocentrism they seek to displace." For further information about the lecture and to RSVP click here or contact [email protected] or 021 650 3730 by Sunday, 13 August 2017 Refreshments will be served . -

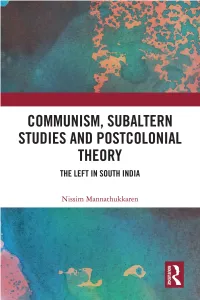

Communism, Subaltern Studies and Postcolonial Theory

COMMUNISM, SUBALTERN STUDIES AND POSTCOLONIAL THEORY This book is a thematic history of the communist movement in Kerala, the first major region (in terms of population) in the world to democratically elect a communist government. It analyzes the nature of the transformation brought about by the communist movement in Kerala, and what its implications could be for other postcolonial societies. The volume engages with the key theoretical concepts in postcolonial theory and Subaltern Studies, and contributes to the debate between Marxism and postcolonial theory, especially its recent articulations. The volume presents a fresh empirical engagement with theoretical critiques of Subaltern Studies and postcolonial theory, in the context of their decades-long scholarship in India. It discusses important thematic moments in Kerala’s communist history which include—the processes by which it established its hegemony, its cultural interventions, the institution of land reforms and workers’ rights, and the democratic decentralization project, and, ultimately, communism’s incomplete national-popular and its massive failures with regard to the caste question. A significant contribution to scholarship on democracy and modernity in the Global South, this volume will be of great interest to scholars and researchers of politics, specifically political theory, democracy and political participation, political sociology, development studies, postcolonial theory, Subaltern Studies, Global South Studies and South Asia Studies. Nissim Mannathukkaren is Associate Professor in the International Development Studies Department at Dalhousie University, Canada. He is the author of the book The Rupture with Memory: Derrida and the Specters That Haunt Marxism (2006). His research has been published in journals such as Citizenship Studies, Journal of Peasant Studies, Third World Quarterly, Economic and Political Weekly, Journal of Critical Realism, International Journal of the History of Sport, Dialectical Anthropology, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies and Sikh Formations. -

SOCI 555: Comparative-Historical Sociology Winter 2018

MCGILL UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY SOCI 555: Comparative-Historical Sociology Winter 2018 Instructor: Dr. Efe Peker Class time: Wednesdays, 9:35-11:25am Class Location: LEA 819 Email: [email protected] Office hours: Wednesdays, 11:30-12:30 Office Location: LEA 735 Office Phone: 514-398-6850 1. Course Overview: Comparative-historical approaches and research methods have been deeply embedded in the sociological imagination since the foundation of the latter as a discipline. It was none other than Émile Durkheim who put forward that sociology and history are “not two separate disciplines, but two different points of view which mutually presuppose each other”. Eclipsed by the behavioural and functionalist schools in the mid-twentieth century, comparative-historical analysis made a comeback in the 1970s to establish itself as a respected branch of sociology, focusing on society- wide transformations happening over long periods. Comparative-historical sociology (CHS) is concerned with how and why various macro-social institutions and phenomena (such as states, markets, revolutions, welfare systems, collective violence, religion, nationalism) emerged and/or evolved in multifaceted ways in different parts of the globe. In showing us the winding and contentious trajectories of the past, it helps us make better sense of the world we live in today. The purpose of this seminar is to familiarize the students with the core theories, methods, issues, and approaches employed in CHS. Organised in seminar form, the course is divided into two parts. Part A lays out the theoretical and methodological underpinnings of sociohistorical inquiry. After an introductory background on the intersecting paths of sociology and history, this part elaborates on the epistemological and ontological assumptions of CHS, various comparative research tools and agendas, data collection and interpretation techniques, as well as notions of temporality and causality in sociohistorical investigation. -

SOCIOLOGY 9191A Social Science in the Marxian Tradition Fall 2020

SOCIOLOGY 9191A Social Science in the Marxian Tradition Fall 2020 DRAFT Class times and location Wednesday 10:30am -12:30pm Virtual synchronous Instructor: David Calnitsky Office Hours by appointment Department of Sociology Office: SSC 5402 Email: [email protected] Technical Requirements: Stable internet connection Laptop or computer Working microphone Working webcam “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.” – Karl Marx That is the point, it’s true—but not in this course. This quote, indirectly, hints at a deep tension in Marxism. If we want to change the world we need to understand it. But the desire to change something can infect our understanding of it. This is a pervasive dynamic in the history of Marxism and the first step is to admit there is a problem. This means acknowledging the presence of wishful thinking, without letting it induce paralysis. On the other hand, if there are pitfalls in being upfront in your desire to change the world there are also virtues. The normative 1 goal of social change helps to avoid common trappings of academia, in particular, the laser focus on irrelevant questions. Plus, in having a set of value commitments, stated clearly, you avoid the false pretense that values don’t enter in the backdoor in social science, which they often do if you’re paying attention. With this caveat in place, Marxian social science really does have a lot to offer in understanding the world and that’s what we’ll analyze in this course. The goal is to look at the different hypotheses that broadly emerge out of the Marxian tradition and see the extent to which they can be supported both theoretically and empirically. -

Conference Participant Bios

Conference Participant Bios: Farshad Araghi, Associate Professor of Sociology, Florida Atlantic University, [email protected] Professor Araghi works in the areas of global sociology, social theory, sociology of agriculture and human displacement, and world-historical analysis. He was a postdoctoral fellow at the Fernand Braudel Center for the Study of Economies, Historical Systems, and Civilizations at Binghamton University and a visiting professor of Development Sociology at Cornell University where he offered graduate seminars in Social Theory, State Economy and Society in Global Context, and Global Perspectives on Rural Economy and Society. For the past decade, he has been a co-editor of the International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food. His article, "Food Regimes and the Production of Value: Some Methodological Remarks," published in Journal of Peasant Studies, Vol. 30, No.2, was awarded the Eric Wolf prize for one of the two best articles appearing in Volume 30 of the journal. Manuela Boatcă, Assistant Professor of Sociology and Latin American Studies, Free University of Berlin, [email protected] Professor Boatcă’s research interests include world system analysis and comparative sociology, social change and inequality, as well as the global political economy. In addition to her work at the FU Berlin, she has been the co-editor of the series Zentrum und Peripherie at Hampp Publishers and a consultant at the Austrian Ministry of Culture. Her publications include: Des Fremden Freund, des Fremden Feind. Fremdverstehen in interdisziplinärer Perspektive (with Claudia Neudecker and Stefan Rinke, 2006); Decolonizing European Sociology. Transdisciplinary Approaches (with Encarnación Gutiérrez Rodríguez and Sérgio Costa (eds.), 2010); and Global Inequalities: Beyond Occidentalism (Ashgate Press 2015). -

The Rise and Domestication of Historical Sociology

The Rise and Domestication of" Historical Sociology Craig Calhoun Historical sociology is not really new, though it has enjoyed a certain vogue in the last twenty years. In fact, historical research and scholarship (including comparative history) was central to the work of many of the founders and forerunners of sociology-most notably Max Weber but also in varying degrees Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim, and Alexis de Tocqueville among others. It was practiced with distinction more recently by sociologists as disparate as George Homans, Robert Merton, Robert Bellah, Seymour Martin Lipset, Charles Tilly, J. A. Banks, Shmuel Eisenstadt, Reinhard Bendix, Barrington Moore, and Neil Smelser. Why then, should historical sociology have seemed both new and controversial in the 1970s and early 1980s? The answer lies less in the work of historical sociologists themselves than in the orthodoxies of mainstream, especially American, sociology of the time. Historical sociologists picked one battle for themselves: they mounted an attack on modernization theory, challenging its unilinear developmental ten- dencies, its problematic histori<:al generalizations and the dominance (at least in much of sociology) of culture and psycllology over political economy. In this attack, the new generation of historical sociologists challenged the most influential of their immediate forebears (and sometimes helped to create the illusion that historical sociology was the novel invention of the younger gener- ation). The other major battle was thrust upon historical sociologists when many leaders of the dominant quantitative, scientistic branch of the discipline dismissed their work as dangerously "idiographic," excessively political, and in any case somehow not quite 'real' sociology. Historical sociology has borne the marks of both battles, and in some sense, like an army always getting ready to fight the last war, it remains unnecessarily preoccupied with them. -

Seminar on Theories of the State

SOCIOLOGY 924 SEMINAR ON THEORIES OF THE STATE Fall Semester, 2002 Professor Erik Olin Wright Department of Sociology University of Wisconsin Madison, Wisconsin Wednesdays, 6:00-8:30, room 8108 Social Science This seminar has two primary objectives: First, to deepen students’ understanding of alternative theoretical approaches to studying the state and politics, and second, to examine a range of interesting empirical/historical studies that embody, in different ways, these approaches in order to gain a better understanding of the relationship between abstract theoretical ideas and concrete empirical investigation. We will focus on three broad theoretical approaches: 1. Marxist or class-analytic approaches which anchor the analysis of the state in terms of its structural relationship to capitalism as a system of class relations. 2. Weberian or organization-analytic approaches which emphasize the ways in which states constitute autonomous sources of power and operate on the basis of institutional logics and dynamics with variable forms of interaction with other sources of power in society. 3. Microfoundational approaches which emphasize the ways in which the actions of states are rooted in the interests, motivations, and strategic dilemmas of the people who occupy positions in the state. While these three approaches have long pedigrees, we will not explore the classical formulations or the historical development of these traditions of analysis, but rather will focus on the most developed versions of each approach. Also, while these approaches are often posed as rivals, in fact much contemporary work combines them in various ways. One of the tasks of the seminar is to examine the ways in which these different traditions of theoretical work complement rather than contradict each other in generating compelling explanations of concrete historical problems of understanding states and politics.