The Dual Legacy of Orientalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edward Said a Critical Introduction

Edward Said Edward Said A Critical Introduction Valerie Kennedy Polity Press Copyright © Valerie Kennedy 2000 The right of Valerie Kennedy to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in 2000 by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd Editorial office: Polity Press 65 Bridge Street Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK Marketing and production: Blackwell Publishers Ltd 108 Cowley Road Oxford OX4 1JF, UK Published in the USA by Blackwell Publishers Inc. Commerce Place 350 Main Street Malden, MA 02148, USA All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. ISBN 0-7456-2018-3 ISBN 0-7456-2019-1 (pbk) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library and has been applied for from the Library of Congress. Typeset in 10.5 on 12 pt Palatino by Best-set Typesetter Ltd., Hong Kong Printed in Great Britain by MPG Books Limited, Bodmin, Cornwall This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

Samir Gandesha1 the Aesthetic Politics of Hegemony

Studi di estetica, anno XLVI, IV serie, 3/2018 ISSN 0585-4733, ISSN digitale 1825-8646, DOI 10.7413/18258646066 Samir Gandesha1 The aesthetic politics of hegemony Abstract In this article, it is argued that Gramsci’s conception of hegemony ought to be located not simply in the theory and praxis of Leninism but also in Gramsci’s read- ing of Machiavelli. By situating such a reading in relation to Nietzsche’s notion of will to power, it is possible to defend Gramsci’s political theory against some of the criticisms leveled by those who decry the “hegemony of hegemony”. Such a reading of the concept of hegemony enables us to understand the idea of “com- mon sense” as oriented towards the distribution and redistribution of the sensible. Keywords Aesthetics, Gramsci, Hegemony 1. Introduction In the introduction to our book Aesthetic Marx (2017), Johan Hartle and I point out that there is one main problem with the Marxological approach to the aesthetic dimensions of Marx’s writings: the classical understanding of the discipline of aesthetics that is presupposed by such exegetical approaches must also be interrogated. “Aesthetics” is normally understood as a philosophical discipline that concerns the conditions for the possibility of judgments of taste, as a specific ra- tionality that maintains its own autonomy, its own purposeless pur- posiveness, against contending and competing the spheres of value (the epistemic, the moral), and that deals with normative criteria in order to evaluate forms of experience and artistic developments on 1 [email protected]. I would like to thank professor Stefano Marino for his extremely helpful suggestions and assistance with this article. -

Feminism, Imperialism and Orientalism: the Challenge of the ‘Indian Woman’

FEMINISM, IMPERIALISM AND ORIENTALISM Women’s History Review, Vol. 7, No. 4, 1998 Feminism, Imperialism and Orientalism: the challenge of the ‘Indian woman’ JOANNA LIDDLE & SHIRIN RAI University of Warwick, Coventry, United Kingdom ABSTRACT This article examines the content and process of imperialist discourse on the ‘Indian woman’ in the writings of two North American women, one writing at the time of ‘first wave’ feminism, the other a key exponent of the ‘second wave’ of the movement. By analysing these writings, it demonstrates how the content of the discourse was reproduced over time with different but parallel effects in the changed political circumstances, in the first case producing the Western imperial powers as superior on the scale of civilisation, and in the second case producing Western women as the leaders of global feminism. It also identifies how the process of creating written images occurred within the context of each author’s social relations with the subject, the reader and the other authors, showing how an orientalist discourse can be produced through the author’s representation of the human subjects of whom she writes; how this discourse can be reproduced through the author’s uncritical use of earlier writers; and how the discourse can be activated in the audience through the author’s failure to challenge established cognitive structures in the reader. Introduction This article has two main aims. First, it examines how aspects of imperialist discourse on the colonised woman were taken up in Western women’s writing at the time of ‘first wave’ feminism, and reproduced in the ‘second wave’ of the movement within the context of the changing power relations between the imperial powers and the former colonies. -

Dialectical Orientalism in Borges

Imaginative Geography: Dialectical Orientalism in Borges ______________________________________________________ SHLOMY MUALEM BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY Abstract The following essay investigates Borges’ cultural-ideological stance as an Argentinean writer opposed to national literature and ideological rhetoric. This position will be elucidated via a comparison with Edward Said’s Orientialism which, following Foucault, argues that literature is subservient to the ideological paradigms of the period. The discussion demonstrates how Borges presents a dialectical orientalism in his work: a philosophical-universal position deviating from the delimited framework of national ideology, hereby establishing an uni-ideological philosophical and transcultural view of the interrelationship between “East” and “West.” In line with Said, the essay examines the literary representation of Islam in Western literature, focusing on the image of Mahomet in Dante's Divine Comedy. “These are the lenses through which the Orient is experienced, and they shape the language, perception, and form of the encounter between East and West” (Said, 1994, 58). Herein, Edward Said trenchantly argues that Western Orientalism is demonic in its power. In his seminal Orientalism (1978), he details the scope, internal consistency, and strata of this vast web of representations the West spreads over the Orient in an attempt to control and master it, believing it to constitute a “creeping danger.” It resembles the labyrinth Daedalus constructed in order to capture the Minotaur. The image of the labyrinth is inaccurate, however, Said in effect believing that the web is so fine and well-made that even Westerners can no longer extract themselves from it. I believe that Said would regard Jorge Luis Borges as an Orientalist par excellence. -

Edward Said: the Postcolonial Theory and the Literature of Decolonization

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by European Scientific Journal (European Scientific Institute) European Scientific Journal June 2014 /SPECIAL/ edition vol.2 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 EDWARD SAID: THE POSTCOLONIAL THEORY AND THE LITERATURE OF DECOLONIZATION Lutfi Hamadi, PhD Lebanese International University, Lebanon Abstract This paper attempts an exploration of the literary theory of postcolonialism, which traces European colonialism of many regions all over the world, its effects on various aspects of the lives of the colonized people and its manifestations in the Western literary and philosophical heritage. Shedding light on the impact of this theory in the field of literary criticism, the paper focuses on Edward Said's views for the simple reason that he is considered the one who laid the cornerstone of this theory, despite the undeniable role of other leading figures. This theory is mainly based on what Said considers the false image of the Orient fabricated by Western thinkers as the primitive "other" in contrast with the civilized West. He believes that the consequences of colonialism are still persisting in the form of chaos, coups, corruption, civil wars, and bloodshed, which permeates many ex-colonies. The powerful colonizer has imposed a language and a culture, whereas those of the Oriental peoples have been ignored or distorted. Referring to some works of colonial and postcolonial novelists, the paper shows how being free from the repression of imperialism, the natives could, eventually, produce their own culture of opposition, build their own image, and write their history outside the frame they have for long been put into. -

Fall 2005 Newsletter of the ASA Comparative and Historical Sociology Section Volume 17, No

________________________________________________________________________ __ Comparative & Historical Sociology Fall 2005 Newsletter of the ASA Comparative and Historical Sociology section Volume 17, No. 1 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ From the Chair: State of the CHS Union SECTION OFFICERS 2005-2006 Richard Lachmann SUNY-Albany Chair Richard Lachmann Columns of this sort are the academic equivalents of State SUNY-Albany of the Union speeches, opportunities to say that all is well and to take credit for the good times. Chair-Elect William Roy I can’t (and won’t) take credit for the healthy state of com- University of California-Los Angeles parative historical sociology but I do want to encourage all of us to recognize the richness of our theoretical discus- sions and the breadth and depth of our empirical work. The Past Chair Jeff Goodwin mid-twentieth century revolution in historiography—the New York University discovery and creative interpretation of previously ignored sources, many created by historical actors whose agency had been slighted and misunderstood—has been succeeded Secretary-Treasurer by the recent flowering of comparative historical work by Genevieve Zubrzycki sociologists. University of Michigan We can see the ambition and reach of our colleagues’ work Council Members in the research presented at our section’s panels in Phila- Miguel A. Centeno, Princeton (2007) delphia and in the plans for sessions next year (see the call Rebecca Jean Emigh, UCLA (2006) for papers elsewhere in this newsletter). The Author Meets Marion Fourade-Gourinchas, Berkeley (2008) Critics panel on Julia Adams, Lis Clemens, and Ann Or- Fatma Muge Gocek, U Michigan (2006) Mara Loveman, UW-Madison (2008) loff’s Remaking Modernity: Politics, History, and Sociol- James Mahoney, Northwestern (2007) ogy was emblematic of how our field’s progress got ex- pressed at the Annual Meeting. -

Orientalism Once More (2003)

Orientalism Once More (2003) Dr Edward Said Professor of Comparative Literature Columbia University Honorary Fellow Instiute of Social Studies Lecture delivered on the occasion of the awarding of the degree of Doctor Honoris Causa at the Academic Ceremony on the 50th Anniversary of the Institute of Social Studies, The Hague, The Netherlands, 21 May, 2003 Orientalism Once More (2003)* Nine years ago, in the spring of 1994, I wrote an afterword for Orientalism which, in trying to clarify what I believed I had and had not said, I stressed not only the many discussions that had opened up since my book appeared in 1978, but the ways in which a work about representations of “the Orient” lent themselves to increasing misrepresentation and misinterpretation. That I find myself feeling more ironic than irritated about that very same thing today is a sign of how much my age has crept up on me, along with the necessary diminutions in expectations and pedagogic zeal which usually frame the road to seniority. The recent death of my two main intellectual, political and personal mentors, Eqbal Ahmad and Ibrahim Abu-Lughod (who is one of this work’s dedicatees), has brought sadness and loss, as well as resignation and a certain stubborn will to go on. It isn’t at all a matter of being optimistic, but rather of continuing to have faith in the ongoing and literally unending process of emancipation and enlightenment that, in my opinion, frames and gives direction to the intellectual vocation. Nevertheless it is still a source of amazement to me that Orientalism continues to be discussed and translated all over the world, in thirty-six languages. -

Micah Hughes on No Exit: Arab Existentialism, Jean-Paul Sartre

Yoav Di-Capua. No Exit: Arab Existentialism, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Decolonization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018. xv + 355 pp. $35.00, paper, ISBN 978-0-226-50350-9. Reviewed by Micah Hughes Published on H-Ideas (August, 2019) Commissioned by Aidan Beatty (University of Pittsburgh) Edward Said once remarked after meeting the would drastically reorient Arab intellectuals’ in‐ famed French philosopher that although he was vestment in Sartre and existentialism as a philo‐ “once the most celebrated intellectual, Jean-Paul sophical and political practice of freedom in the Sartre had, until quite recently, almost faded from aftermath of colonialism. Prior to these two mo‐ view.”[1] Said’s unfavorable account of his meet‐ ments, especially the Six-Day War in 1967, Sartre ing with Sartre and his withered prominence in had shown sustained interest in the politics of de‐ Europe and beyond was published in 2000 but re‐ colonization in the Middle East and the plight of counted a meeting between the two that occurred the Palestinians. However, his dedication to decol‐ more than twenty years prior, in 1979. His obser‐ onization in the region was marked by ambiva‐ vation comes as no surprise to those familiar with lence towards Palestinian claims to territorial the postwar French intellectual context in which sovereignty in the face of European guilt for the existentialism had given way to criticisms of hu‐ Holocaust. In the words of Peter Makhlouf, Said’s manism, frst articulated in the linguistic and account of Sartre “attempt[ed] to -

Selected Bibliography of Work About and of Edward Said's Texts

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 5 (2003) Issue 4 Article 7 Selected Bibliography of Work about and of Edward Said's Texts Clare Callaghan University of Maryland Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Callaghan, Clare. "Selected Bibliography of Work about and of Edward Said's Texts." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 5.4 (2003): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1203> The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 13859 times as of 11/07/19. -

Edward W. Said: Resistance, Knowledge, Criticism

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository Edward W. Said: Resistance, Knowledge, Criticism by Mark Anthony Taylor A Doctoral Thesis Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy of Loughborough University 17th October 2016 © Mark Taylor 2016 Abstract The prodigious output of the controversial Palestinian-American public intellectual, academic, and political activist, Edward W. Said (1935-2003), continues to polarize the academic, intellectual, and political worlds, not least because of the inflammatory nature of his relationship to the vexed issue of Israel/Palestine. It is a contention of this thesis that this polarization has resulted in what are often less than critical examinations of Said’s work. In short, because Said and his work remain relevant and influential, a new method of reading is required, one which not only takes account of Said’s resolutely secular, ‘worldly’ approach to the issue of knowledge and its production, but applies the same rigour and method to the Palestinian’s work in all its literary-critical, political, and personal varieties. This thesis attempts to meet that aim by testing Said’s oeuvre within the rubric of his stated ambition to create a critical location from which the production of ‘non-coercive knowledge’ was attainable. In the context of his opposition to political Zionism and wider Western imperialism, whether Said produced, or even intended to produce, knowledge that was ‘non-coercive’ is an extremely important question, and one that will be answered in this thesis. Formed by an introduction and three main chapters, the scope of the thesis is broad. -

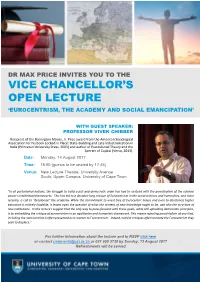

Vice Chancellor's Open Lecture

DR MAX PRICE INVITES YOU TO THE VICE CHANCELLOR’S OPEN LECTURE ‘EUROCENTRISM, THE ACADEMY AND SOCIAL EMANCIPATION’ WITH GUEST SPEAKER: PROFESSOR VIVEK CHIBBER Recipient of the Barrington Moore, Jr. Prize award from the American Sociological Association for his book Locked in Place: State-Building and Late Industrialization in India (Princeton University Press, 2003) and author of Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital (Verso, 2013). Date: Monday, 14 August 2017 Time: 18:00 (guests to be seated by 17:45) Venue: New Lecture Theatre, University Avenue South, Upper Campus, University of Cape Town "In all postcolonial nations, the struggle to build a just and democratic order has had to contend with the parochialism of the colonial power’s intellectual frameworks. This has led to a decades-long critique of Eurocentrism in the social sciences and humanities, and more recently, a call to “decolonize” the academy. While the commitment to wrest free of Eurocentric biases and even to decolonize higher education is entirely laudable, it leaves open the question of what the content of new knowledge ought to be, and also the structure of new institutions. In this lecture I suggest that the only way to press forward with these goals, while still upholding democratic principles, is by embedding the critique of eurocentrism in an egalitarian and humanistic framework. This means rejecting parochialism of any kind, including the nativism that is often presented as a counter to Eurocentrism. Indeed, nativist critiques often recreate the Eurocentrism they seek to displace." For further information about the lecture and to RSVP click here or contact [email protected] or 021 650 3730 by Sunday, 13 August 2017 Refreshments will be served . -

Said-Introduction and Chapter 1 of Orientalism

ORIENTALISM Edward W. Said Routledge & Kegan Paul London and Henley 1 First published in 1978 by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. 39 Store Street, London WCIE 7DD, and Broadway House, Newton Road, Henley-on-Thames, Oxon RG9 1EN Reprinted and first published as a paperback in 1980 Set in Times Roman and printed in Great Britain by Redwood Burn Limited Trowbridge & Esher © Edward W. Said 1978 No Part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passage in criticism. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Said, Edward W. Orientalism, 1. East – Study and teaching I. Title 950’.07 DS32.8 78-40534 ISBN 0 7100 0040 5 ISBN 0 7100 0555 5 Pbk 2 Grateful acknowledgements is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.: Excerpts from Subject of the Day: Being a Selection of Speeches and Writings by George Nathaniel Curzon. George Allen & Unwin Ltd.: Excerpts from Revolution in the Middle East and Other Case Studies, proceedings of a seminar, edited by P. J. Vatikiotis. American Jewish Committee: Excerpts from “The Return of Islam” by Bernard Lewis, in Commentary, vol. 61, no. 1 (January 1976).Reprinted from Commentary by permission.Copyright © 1976 by the American Jewish Committee. Basic Books, Inc.: Excerpts from “Renan’s Philological Laboratory” by Edward W. Said, in Art, Politics, and Will: Essarys in Honor of Lionel Trilling, edited by Quentin Anderson et al. Copyright © 1977 by Basic Books, Inc. The Bodley Head and McIntosh & Otis, Inc.: Excerpts from Flaubert in Egypt, translated and edited by Franscis Steegmuller.Reprinted by permission of Francis Steegmuller and The Bodley Head.