The Foundations and Development of Anti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BORGES's MEDIEVAL IBERIA by Maria Ruhlmann a Dissertation

BORGES’S MEDIEVAL IBERIA by Maria Ruhlmann A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor in Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland March 1, 2017 © Maria Ruhlmann All Rights Reserved Abstract This dissertation examines how and why famed Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges conjures up images of Medieval Iberia in the vast majority of his anthologies of essays, poems and stories. Following an introduction to Borges’s attitude to the multiple and often contradictory appropriations of Medieval Iberia in the Spanish-speaking world of his day, it considers the philological and postcolonial implications of Borges’s references to al-Andalus and Sepharad. Relying on New Philology as defined by Karla Mallette and on postcolonial approaches to medievalisms of the postcolonial world, Borges’s Medieval Iberia offers a contribution to the mostly unchartered territory of critical approaches to the uses of medievalisms in twentieth- century Argentina. Advisors: Nadia Altschul Eduardo González ii Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... ii Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... iii A Note on Translation, Spelling and Terminology ......................................................................... 1 Introduction: Borges’s Unacknowledged Medieval Iberia ............................................................ -

Tokarska-Bakir the Kraków Pogrom the Kraków Pogrom of 11 August

Tokarska-Bakir_The Kraków pogrom The Kraków Pogrom of 11 August 1945 against the Comparative Background 1. The aim of the conducted research/the research hypothesis The subject of the project is the analysis of the Kraków pogrom of August 1945 against the background of the preceding similar events in Poland (Rzeszów, June 1945) and abroad (Lviv, June 1945), as well as the Slovak and Hungarian pogroms at different times and places. The undertaking is a continuation of the research described in my book "Pod klątwą. Społeczny portret pogromu kieleckiego" (2018), in which I worked out a methodology of microhistorical analysis, allowing the composition of a pogrom crowd to be determined in a maximally objective manner. Thanks to the extensive biographical query it was possible to specify the composition of the forces of law and order of the Citizens' Militia (MO), the Internal Security Corps (KBW), and the Polish Army that were sent to suppress the Kielce pogrom, as well as to put forward hypotheses associated with the genesis of the event. The question which I will address in the presented project concerns the similarities and differences that exist between the pattern according to which the Kielce and Kraków pogroms developed. To what extent did the people who were within the structures of the forces of law and order, primarily communist militia, take part in it –those who murdered Jews during the war? Are the acts of anti-Semitic violence on the Polish, Ukrainian, and Slovak lands structurally similar or fundamentally different? What are the roles of the legend of blood (blood libel), the stereotype of Żydokomuna (Jewish communists), and demographical panic and panic connected with equal rights for Jews, which destabilised traditional social relations? In the framework of preparatory work I managed to initiate the studies on the Kraków pogrom in the IPN Archive (Institute of National Remembrance) and significantly advance the studies concerning the Ukrainian, Hungarian, and Slovak pogroms (the query was financed from the funds from the Marie Curie grant). -

The Libro Verde: Blood Fictions from Early Modern Spain

INFORMATION TO USERS The negative microfilm of this dissertation was prepared and inspected by the school granting the degree. We are using this film without further inspection or change. If there are any questions about the content, please write directly to the school. The quality of this reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original material The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When it is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to indicate this. 3. Oversize materials (maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sec tioning the original, beginning at the upper left hand comer and continu ing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Dissertation Information Service A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 9731534 Copyright 1997 by Beusterien, John L. All rights reserved. UMI Microform 9731534 Copyright 1997, by UMI Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Titic 17, United States Code. UMI 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, MI 48103 Reproduced with permission -

Jewish Studies Connects

ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY Jewish Studies 2020 annual report about the cover In 2019, while taking REL/ JST 315: Hebrew Bible, with lecturer Timothy Langille— who teaches courses on the Hebrew Bible and Jewish history—Alison Sigala crafted a highly elaborate scroll with medieval-like art, which portrays the stories from the first two chapters of Ezekiel in the Hebrew Bible. According to Dr. Langille, it also relates to one of the units discussed in this class, “book cultures versus scroll cultures.” The work depicts the biblical scene of Ezekiel receiving a vision from G-d, who calls him to become a prophet. In this story, Ezekiel receives a scroll from G-d and then eats it. Sigala said this inspired her to use a scroll and artistically represent how she interpreted table of contents his vision. from the director 1 Dr. Langille suggests “Call to Prophecy” from Ezekiel 1 contains some of the most celebrating a decade 2 “over-the-top imagery in the Hebrew Bible.” To visualize the imagery, “conceptualize center life 6 it and produce this is pretty amazing,” he said. library update 18 Events in Ezekiel are depicted chronologically from the top faculty activities 20 to the bottom of the scroll through vibrant, visceral student news 28 imagery produced with acrylic paint and Sharpie ink on mulberry print-making paper. philanthropy 40 Hava Tirosh-Samuelson Director, Jewish Studies from the director This report celebrates the accomplishments of ASU Jewish Studies during the 2018-2019 and 2019-2020 academic years. For all of these accomplishments, I am deeply grateful to, and appreciative of: Jewish Studies staff Lisa Kaplan, Assistant Director and Dawn Beeson, Coordinator Senior for their dedication and hard work. -

Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate

Fordham University DigitalResearch@Fordham Faculty Publications Jewish Studies 2020 Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/jewish_facultypubs Part of the History Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fordham University, "Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate" (2020). Faculty Publications. 2. https://fordham.bepress.com/jewish_facultypubs/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jewish Studies at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Media Technology & The Dissemination of Hate November 15th, 2019-May 31st 2020 O’Hare Special Collections Fordham University & Center for Jewish Studies Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate Highlights from the Fordham Collection November 15th, 2019-May 31st, 2020 Curated by Sally Brander FCRH ‘20 Clare McCabe FCRH ‘20 Magda Teter, The Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies with contributions from Students from the class HIST 4308 Antisemitism in the Fall of 2018 and 2019 O’Hare Special Collections Walsh Family Library, Fordham University Table of Contents Preface i Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate 1 Christian (Mis)Interpretation and (Mis)Representation of Judaism 5 The Printing Press and The Cautionary Tale of One Image 13 New Technology and New Opportunities 22 -

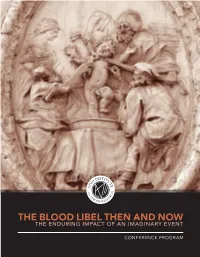

Read the Conference Program

COVER: Stone medallion with the purported martyrdom scene of Simonino di Trento. Palazzo Salvadori, Trent, Italy. Photo by Andreas Caranti. Via Wikimedia Commons. YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH PRESENTS CONFERENCE OCTOBER 9, 2016 CO-SPONSORED BY 1 INCE ITS FABRICATION IN THE MIDDLE AGES, the accusation that Jews Skidnapped, tortured and killed Christian children in mockery of Christ and the Crucifixion, or for the use of their blood, has been the basis for some of the most hateful examples of organized antisemitism. The blood libel has inspired expulsions and murder of Jews, tortures and forced mass conversions, and has served as an ines- capable focal point for wider strains of anti-Jewish sentiment that permeate learned and popular discourse, social and political thought, and cultural media. In light of contemporary manifestations of antisemitism around the world it is appropriate to re-examine the enduring history, the wide dissemination, and the persistent life of a historical and cultural myth—a bald lie—intended to demonize the Jewish people. This conference explores the impact of the blood libel over the centuries in a wide variety of geographic regions. It focuses on cultural memory: how cultural memory was created, elaborated, and transmitted even when based on no actual event. Scholars have treated the blood libel within their own areas of expertise—as medieval myth, early modern financial incentive, racial construct, modern catalyst for pogroms and the expulsion of Jews, and political scare tactic—but rarely have there been opportunities to discuss such subjects across chronological and disciplinary borders. We will look at the blood libel as historical phenomenon, legal justification, economic mechanism, and visual and literary trope with ongoing political repercussions. -

Mythologizing the Jewish Other in the “Prioress's Tale”

MYTHOLOGIZING THE JEWISH OTHER IN THE “Prioress’s Tale” Barbara Stevenson For a religious system like Christianity to prosper, it must convince members that it is the divinely-sanctioned charter upon which the com- munity is based, and it must adapt to cultural changes over time. These demands create a paradoxical situation: a theology must appear to be a timeless, fixed truth while at the same time reinventing itself as histori- cal events reshape a community. To succeed, such a system needs “plas- ticity,” Raymond Firth’s term for the chameleon-like quality of myth to appear timeless while altering its form to fit new situations.1 As a mytho- logical system, Christianity has its sacred origin in the Gospels’ narratives of Jesus’s crucifixion at the hands of his Roman and Jewish enemies and his subsequent resurrection. For the Christianity of late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, the written legends of saints provided one means of revis- ing the original sacred charter. Surrogates for Jesus, saints re-enacted this mythic origin with their martyrdom and miracles recorded in hagiography and provided variations that depart from the original myth by adapting to changing situations. Ritualistic celebrations of recorded saints’ lives allowed Christians to form a community and an identity separate from the Other who tried to vanquish their Christ and saints.2 In one medieval hagiographical tradition, Christian children—evoking the Christ Child who as an adult would be crucified—became martyrs at the hands of Jews, seen as the medieval descendants of those who participated in the deicide of Jesus Christ. -

The Circumcision Case of Odard and the Legacy of St William of Norwich

6 The Missing Accusation: The Circumcision Case of Odard and the Legacy of St William of Norwich Julia Tomlinson Introduction The ritual murder accusation has a long and clear history of anti-Judaic sentiment. This accusation was first made in England regarding the death of St William of Norwich in 1144. Yet it is unclear whether the lay community of Norwich actually experienced this cult in an anti- Judaic way: did they in fact associate St William with ritual murder and antagonistic feelings towards their Jewish neighbors? Evidence for his cult in the first 150 years is lacking. I believe, however, that by looking at available information on the cult alongside Jewish-Christian relations in the town, we can see that Christians in the lay community did not associate the cult with ritual murder, nor was it likely associated with strong anti-Judaic sentiment. This is especially clear when one examines the case of Odard, a Christian boy in Norwich who in 1230 was circumcised by Jews. Despite the physical, religiously-motivated nature of the crime, there were no accusations of ritual murder within Norwich. This missing accusation shows that the possibility of ritual murder—and the memory of St William—did not weigh heavily on the laity’s mind. If they felt the real presence of St William’s cult and the anti-Judaic sentiment associated with it, the Christian lay community of Norwich would associate ritual murder with Odard’s case. Ritual Murder Accusations: Truth or Fiction? In discussing the anti-Judaic nature of ritual murder accusations, we must first establish if there is any truth to such accusations. -

Sir Hugh of Lincoln — from History to Nursery Rhyme

KARL HEINZ GÖLLER Sir Hugh of Lincoln — From History to Nursery Rhyme / Historical Background 1.1 The Myth of the Jewish Ritual Murder All ascertainable historical facts concerning the alleged murder of Hugh of Lincoln are connected, in one way or another, with the myth of the Jewish ritual murder, which was widespread in England during the Middle Ages. It had been given new momentum through the murder of a young boy named William of Norwich in the year 1144.1 In this connection the Jewish apostate 1 The child martyr Hugh of Lincoln is often confused with the famous Bishop Hugh of Lincoln. On his vita, see Life of Hugh of Lincoln, ed. James Francis Dimock, R. S. (London, 1864); on the murder of William of Norwich, see M. D. Anderson, A Saint at Stake: The Strange Death of William of Norwich, 1144 (London, 1964), which also contains much back• ground information pertinent to the Hugh of Lincoln story; on Copin and John of Lexington, see 106—108. On the alleged "Jewish blood ritual", cf. Hermann L. Strack, Das Blut im Glau• ben und Aberglauben der Menschheit: Mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der "Volksmedizin" und des "jüdi• schen Blutritus" (München, 8th ed. 1900), esp. Chap. 18: "Das angebliche Zeugnis der Geschichte für jüdische Ritualmorde", 121 ff. On the modern view of the facts behind the story, see "Hugh of Lincoln", DNB, XXVIII, 169—171. The traditional medieval view is still predominant in Thomas Fuller, The History of the Worthies of England, 3 vols. (London, 1840; rpt. New York, 1965); here II, 271. -

Course Description Fall 2013

COURSE DESCRIPTION FALL 2013 TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL STUDY ABROAD ‐ FALL SEMESTER 2013 COURSE DESCRIPTION MAIN OFFICE UNITED STATES CANADA The Carter Building , Room 108 Office of Academic Affairs Lawrence Plaza Ramat Aviv, 6997801, Israel 39 Broadway, Suite 1510 3130 Bathurst Street, Suite 214 Phone: +972‐3‐6408118 New York, NY 10006 Toronto, Ontario M6A 2A1 Fax: +972‐3‐6409582 Phone: +1‐212‐742‐9030 [email protected] [email protected] Fax: +1‐212‐742‐9031 [email protected] INTERNATIONAL.TAU.AC.IL 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ■ FALL SEMESTER 2013 DATES 3‐4 ■ ACADEMIC REQUIREMENTS 6‐17 O INSTRUCTIONS FOR REGISTRATION 6‐7 O REGULAR UNIVERSITY COURSES 7 O WITHDRAWAL FROM COURSES 8 O PASS/FAIL OPTION 8 O INCOMPLETE COURSES 8 O GRADING SYSTEM 9 O CODE OF HONOR AND ACADEMIC INTEGRITY 9 O RIGHT TO APPEAL 10 O SPECIAL ACCOMMODATIONS 10 O HEBREW ULPAN REGULATIONS 11 O TAU WRITING CENTER 11‐12 O DESCRIPTION OF LIBRARIES 13 O MOODLE 13 O SCHEDULE OF COURSES 14‐16 O EXAM TIMETABLE 17 ■ TRANSCRIPT REQUEST INSTRUCTIONS 18 ■ COURSE DESCRIPTIONS 19‐97 ■ REGISTRATION FORM FOR STUDY ABROAD COURSES 98 ■ EXTERNAL REGISTRATION FORM 99 2 FALL SEMESTER 2013 IMPORTANT DATES ■ The Fall Semester starts on Sunday, October 6th 2013 and ends on Thursday, December 19th 2013. ■ Course registration deadline: Thursday, September 8th 2013. ■ Class changes and finalizing schedule (see hereunder): October 13th – 14th 2013. ■ Last day in the dorms: Sunday, December 22nd 2013. Students are advised to register to more than the required 5 courses but not more than 7 courses. -

Jewish Mysticism, Ritual Murder, and the Trial of Mendel Beilis

Swarthmore College Works History Faculty Works History 2015 Connecting The Dots: Jewish Mysticism, Ritual Murder, And The Trial Of Mendel Beilis Robert Weinberg Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-history Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Robert Weinberg. (2015). "Connecting The Dots: Jewish Mysticism, Ritual Murder, And The Trial Of Mendel Beilis". Word And Image In Russian History: Essays In Honor Of Gary Marker. 238-252. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-history/464 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Connecting the Dots: Jewish Mysticism, Ritual Murder, and the Trial of Mendel Beilis Robert Weinberg (Swarthmore College) he prosecution of Mendel Beilis for the murder of thirteen-year-old TAndrei Iushchinskii in Kiev a century ago is perhaps the most publi- cized instance of blood libel since the torture and execution of Jews accused of ritually murdering the infant Simon of Trent in 1475. By the time of the trial in the fall of 1913, the Beilis case had become an inter- national cause célèbre. Like the trials of Alfred Dreyfus in the 1890s and the outcry that accompanied the Damascus Affair in the 1840s, the arrest, incarceration, and trial of Beilis aroused public criticism of Russia’s treatment of Jews and inspired opponents of the autocracy at home and abroad to launch a campaign to condemn the trial. -

A History of Antisemitism Fall 2019

A History of Antisemitism Fall 2019 Dr. Katherine Aron-Beller Tel Aviv University International [email protected] _____________________________________________________________________ An analysis of articulated hatred toward Jews as a historical force. After treating precursors in the pagan world of antiquity and in classical Christian doctrine, the course will focus on the modern phenomenon crystallizing in 19th-century Europe and reaching its lethal extreme in Nazi ideology, propaganda, and policy. Expressions in the U.S. and in the Arab world, as well as Jewish reactions to antisemitism, will also be studied. Course Outline 1. Wednesday 23td October: Antisemitism – the oldest hatred Gavin Langmuir, Toward a Definition of Antisemitism. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990)pp. 311-352. Peter Schäfer, Judaeophobia: Attitudes Toward the Jews in the Ancient World. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1997, pp. 34-64, 197-211. 2. Monday 28th October: Jews as Christ Killers – the deepest accusation New Testament (any translation): Matthew 23; 26:57-27:54; John 5:37-40, 8:37-47 John Chrysostom, Discourses Against Judaizing Christians, Homily 1 at: www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/chrysostom-jews6.html Marcel Simon, Verus Israel. Oxford: Littman Library, 1986, pp. 179-233. 3. Wednesday 30th October: The Crusades: The First Massacre of the Jews Soloman bar Samson: The Crusaders in Mainz, May 27, 1096 at: www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1096jews-mainz.html Robert Chazan, “Anti-Jewish violence of 1096 – Perpetrators and dynamics” in Anna Sapir Abulafia Religious Violence between Christians and Jews (Palgrave, 2002) Daniel Lasker, “The Impact of the Crusades on the Jewish-Christian debate” Jewish History 13, 2 (1999) 23-26 4.