The Blood Libel in Eastern Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tokarska-Bakir the Kraków Pogrom the Kraków Pogrom of 11 August

Tokarska-Bakir_The Kraków pogrom The Kraków Pogrom of 11 August 1945 against the Comparative Background 1. The aim of the conducted research/the research hypothesis The subject of the project is the analysis of the Kraków pogrom of August 1945 against the background of the preceding similar events in Poland (Rzeszów, June 1945) and abroad (Lviv, June 1945), as well as the Slovak and Hungarian pogroms at different times and places. The undertaking is a continuation of the research described in my book "Pod klątwą. Społeczny portret pogromu kieleckiego" (2018), in which I worked out a methodology of microhistorical analysis, allowing the composition of a pogrom crowd to be determined in a maximally objective manner. Thanks to the extensive biographical query it was possible to specify the composition of the forces of law and order of the Citizens' Militia (MO), the Internal Security Corps (KBW), and the Polish Army that were sent to suppress the Kielce pogrom, as well as to put forward hypotheses associated with the genesis of the event. The question which I will address in the presented project concerns the similarities and differences that exist between the pattern according to which the Kielce and Kraków pogroms developed. To what extent did the people who were within the structures of the forces of law and order, primarily communist militia, take part in it –those who murdered Jews during the war? Are the acts of anti-Semitic violence on the Polish, Ukrainian, and Slovak lands structurally similar or fundamentally different? What are the roles of the legend of blood (blood libel), the stereotype of Żydokomuna (Jewish communists), and demographical panic and panic connected with equal rights for Jews, which destabilised traditional social relations? In the framework of preparatory work I managed to initiate the studies on the Kraków pogrom in the IPN Archive (Institute of National Remembrance) and significantly advance the studies concerning the Ukrainian, Hungarian, and Slovak pogroms (the query was financed from the funds from the Marie Curie grant). -

Project: Representations of Host Desecration in Medieval Aragon

Project: Representations of Host Desecration in Medieval Aragon The accusation of host desecration by Jews in the Middle Ages was a pan- European phenomenon driven by Christian ideology in tandem with more local political and social concerns. The host was perhaps the most heavily invested and, as a result, the most volatile Christian symbol, representing at once the body of Christ and the body of Christian believers. At different times and different places, accusations of host desecration were used to define boundaries and communities, others and enemies. The NEH Institute on the Medieval Mediterranean allowed me to lay the groundwork for a study of several such accusations that occurred in the Kingdom of Aragon during the second half of the fourteenth century as well as of artistic representations of host desecration from the same area and period. During the month-long institute I focused primarily on one artistic representation and one documented case of host desecration: the altarpiece from the monastery of Santa María de Vallbona de les Monges, now in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya; and the case of host ‘desecration’ that occurred in Barcelona in 1367. The Corpus Christi altarpiece was painted, perhaps by Guillem Seguer, around 1335-1345 for the Corpus Christi chapel in the monastery of Santa María de Vallbona de les Monges, located in the county of Urgell. The retaule and its accompanying frontal are organized, literally and figuratively, around the Eucharistic wafer that one sees in the representation of the Trinity and in an array of scenes drawn from wide variety of source types. -

The Libro Verde: Blood Fictions from Early Modern Spain

INFORMATION TO USERS The negative microfilm of this dissertation was prepared and inspected by the school granting the degree. We are using this film without further inspection or change. If there are any questions about the content, please write directly to the school. The quality of this reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original material The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When it is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to indicate this. 3. Oversize materials (maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sec tioning the original, beginning at the upper left hand comer and continu ing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Dissertation Information Service A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 9731534 Copyright 1997 by Beusterien, John L. All rights reserved. UMI Microform 9731534 Copyright 1997, by UMI Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Titic 17, United States Code. UMI 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, MI 48103 Reproduced with permission -

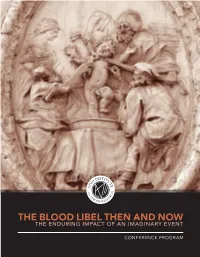

Read the Conference Program

COVER: Stone medallion with the purported martyrdom scene of Simonino di Trento. Palazzo Salvadori, Trent, Italy. Photo by Andreas Caranti. Via Wikimedia Commons. YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH PRESENTS CONFERENCE OCTOBER 9, 2016 CO-SPONSORED BY 1 INCE ITS FABRICATION IN THE MIDDLE AGES, the accusation that Jews Skidnapped, tortured and killed Christian children in mockery of Christ and the Crucifixion, or for the use of their blood, has been the basis for some of the most hateful examples of organized antisemitism. The blood libel has inspired expulsions and murder of Jews, tortures and forced mass conversions, and has served as an ines- capable focal point for wider strains of anti-Jewish sentiment that permeate learned and popular discourse, social and political thought, and cultural media. In light of contemporary manifestations of antisemitism around the world it is appropriate to re-examine the enduring history, the wide dissemination, and the persistent life of a historical and cultural myth—a bald lie—intended to demonize the Jewish people. This conference explores the impact of the blood libel over the centuries in a wide variety of geographic regions. It focuses on cultural memory: how cultural memory was created, elaborated, and transmitted even when based on no actual event. Scholars have treated the blood libel within their own areas of expertise—as medieval myth, early modern financial incentive, racial construct, modern catalyst for pogroms and the expulsion of Jews, and political scare tactic—but rarely have there been opportunities to discuss such subjects across chronological and disciplinary borders. We will look at the blood libel as historical phenomenon, legal justification, economic mechanism, and visual and literary trope with ongoing political repercussions. -

From Ritual Crucifixion to Host Desecration 25 Derived the Information He Put to Such Disastrous Use at Lincoln

Jewish History 9Volume 12, No. 1 9Spring 1998 From Ritual Cruc,ifixion to Host Desecration: Jews and the Body of Christ Robert C. Stacey That Jews constitute a threat to the body of Christ is the oldest, and arguably the most unchanging, of all Christian perceptions of Jews and Judaism. It was, after all, to make precisely this point that the redactors of the New Testament reassigned resPonsibility for Jesus's crucifixion from the Roman governor who ordered it, to an implausibly well-organized crowd of "Ioudaioi" who were alleged to have approved of it. 1 In the historical context of first-century CE Roman Judea, it is by no means clear who the New Testament authors meant to comprehend by this term loudaioi. To the people of the Middle Ages, however, there was no ambiguity, ludaei were Jews; and the contemporary Jews who lived among them were thus regarded as the direct descendants of the Ioudaioi who had willingly taken upon themselves and their children the blood of Jesus that Pilate had washed from his own hands. 2 In the Middle Ages, then, Christians were in no doubt that Jews were the enemies of the body of Christ. 3 There was considerably more uncertainty, however, as to the nature and identity of the body of Christ itself. The doctrine of the resurrection imparted a real and continuing life to the historical, material body of Christ; but it also raised important questions about the nature of that risen body, and about the relationship between that risen body and the body of Christian believers who were comprehended within it. -

Jewish Mysticism, Ritual Murder, and the Trial of Mendel Beilis

Swarthmore College Works History Faculty Works History 2015 Connecting The Dots: Jewish Mysticism, Ritual Murder, And The Trial Of Mendel Beilis Robert Weinberg Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-history Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Robert Weinberg. (2015). "Connecting The Dots: Jewish Mysticism, Ritual Murder, And The Trial Of Mendel Beilis". Word And Image In Russian History: Essays In Honor Of Gary Marker. 238-252. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-history/464 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Connecting the Dots: Jewish Mysticism, Ritual Murder, and the Trial of Mendel Beilis Robert Weinberg (Swarthmore College) he prosecution of Mendel Beilis for the murder of thirteen-year-old TAndrei Iushchinskii in Kiev a century ago is perhaps the most publi- cized instance of blood libel since the torture and execution of Jews accused of ritually murdering the infant Simon of Trent in 1475. By the time of the trial in the fall of 1913, the Beilis case had become an inter- national cause célèbre. Like the trials of Alfred Dreyfus in the 1890s and the outcry that accompanied the Damascus Affair in the 1840s, the arrest, incarceration, and trial of Beilis aroused public criticism of Russia’s treatment of Jews and inspired opponents of the autocracy at home and abroad to launch a campaign to condemn the trial. -

A History of Antisemitism Fall 2019

A History of Antisemitism Fall 2019 Dr. Katherine Aron-Beller Tel Aviv University International [email protected] _____________________________________________________________________ An analysis of articulated hatred toward Jews as a historical force. After treating precursors in the pagan world of antiquity and in classical Christian doctrine, the course will focus on the modern phenomenon crystallizing in 19th-century Europe and reaching its lethal extreme in Nazi ideology, propaganda, and policy. Expressions in the U.S. and in the Arab world, as well as Jewish reactions to antisemitism, will also be studied. Course Outline 1. Wednesday 23td October: Antisemitism – the oldest hatred Gavin Langmuir, Toward a Definition of Antisemitism. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990)pp. 311-352. Peter Schäfer, Judaeophobia: Attitudes Toward the Jews in the Ancient World. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1997, pp. 34-64, 197-211. 2. Monday 28th October: Jews as Christ Killers – the deepest accusation New Testament (any translation): Matthew 23; 26:57-27:54; John 5:37-40, 8:37-47 John Chrysostom, Discourses Against Judaizing Christians, Homily 1 at: www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/chrysostom-jews6.html Marcel Simon, Verus Israel. Oxford: Littman Library, 1986, pp. 179-233. 3. Wednesday 30th October: The Crusades: The First Massacre of the Jews Soloman bar Samson: The Crusaders in Mainz, May 27, 1096 at: www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1096jews-mainz.html Robert Chazan, “Anti-Jewish violence of 1096 – Perpetrators and dynamics” in Anna Sapir Abulafia Religious Violence between Christians and Jews (Palgrave, 2002) Daniel Lasker, “The Impact of the Crusades on the Jewish-Christian debate” Jewish History 13, 2 (1999) 23-26 4. -

Jews and Altarpieces in Medieval Spain

jews and altarpieces in medieval spain 76 JEWS AND 77 ALTARPIECES IN MEDIEVAL SPAIN — Vivian B. Mann INTRODUCTION t first glance, the title of this essay may seem to be an oxymoron, but the reali- ties of Jewish life under Christian rule in late medieval Spain were subtle and complicated, even allowing Jews a role in the production of church art. This essay focuses on art as a means of illuminating relationships between Chris- tians and Jews in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Historians continue to discuss whether the convivencia that characterized the earlier Islamic rule on the Iberian Peninsula continued after the Christian Reconquest, the massacres following the Black Death in 1348 and, especially, after the persecutions of 1391 that initiated a traumatic pe- riod lasting until 1416. One view is that the later centuries of Jewish life on the Peninsula were largely a period of decline that culminated in the Expulsion from Spain in 1492 and the Expulsion from Portugal four years later. As David Nirenberg has written, “Violence was a central and systematic aspect of the coexistence of the majority and minorities of medieval Spain.”1 Other, recent literature emphasizes the continuities in Jewish life before and after the period 1391–1416 that witnessed the death of approximately one-third of the Jewish population and the conversion of another third to one half.2 As Mark Meyerson has noted, in Valencia and the Crown of Aragon, the horrific events of 1391 were sudden and unexpected; only in Castile can they be seen as the product of prolonged anti-Jewish activity.3 Still the 1391 pogroms were preceded by attacks on Jews during Holy Week, for example those of 1331 in Girona.4 Nearly twenty years ago Thomas Glick definedconvivencia as “coexistence, but.. -

Antisemitism

Antisemitism Hatred of Jews as a people or of "the Jew" as a concept. The term “antisemitism” was first coined in the late 1870s, subsequently it is used with reference to all types of Jew-hatred - both historical and contemporary. The word itself comes from the idea that Hebrew belongs to the Semitic language family, and thus Jews must be "Semites." Many other languages also belong to the Semitic language family, such as Arabic and Amharic, and therefore other cultures could also be called "Semites." However, there is no such thing as "Semitism" and no other groups have ever been included in the hatred and prejudice denoted by antisemitism. The word itself is a good example of how, during the late nineteenth century, Jew-haters pretended that their hatred had its basis in scholarly and scientific ideas. Jew-hatred is not a modern phenomenon—it may be traced back to ancient times. Traditional antisemitism is based on religious discrimination against Jews by Christians. Christian doctrine was ingrained with the idea that Jews were responsible for the death of Jesus, and thus deserved to be punished (this is known as the Deicide, or Killing of God, Myth). Another concept that provoked hatred of Jews amongst Christians was the Supercession Myth, claiming that Christianity had replaced Judaism, due to the Jewish People’s failure in their role as the Chosen People of God—and thus deserving punishment, specifically by the Christian world. Over the centuries various stereotypes about Jews developed. Individual Jews were not judged based on their personal achievements or merits, but rather were seen on the whole as greedy, devilish, standoffish, lazy, money-grubbing, and over-sexed. -

Antisemitism, Secularism, and the Catholic Church in the European Union

ANTISEMITISM, SECULARISM, AND THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE EUROPEAN UNION An Undergraduate Research Scholars Thesis by MADISON COWART Submitted to the LAUNCH: Undergraduate Research office at Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of requirements for the designation as an UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH SCHOLAR Approved by Faculty Research Advisor: Dr. Alexander Pacek May 2021 Major: Political Science Copyright © 2021. Madison Cowart. RESEARCH COMPLIANCE CERTIFICATION Research activities involving the use of human subjects, vertebrate animals, and/or biohazards must be reviewed and approved by the appropriate Texas A&M University regulatory research committee (i.e., IRB, IACUC, IBC) before the activity can commence. This requirement applies to activities conducted at Texas A&M and to activities conducted at non-Texas A&M facilities or institutions. In both cases, students are responsible for working with the relevant Texas A&M research compliance program to ensure and document that all Texas A&M compliance obligations are met before the study begins. I, Madison Cowart, certify that all research compliance requirements related to this Undergraduate Research Scholars thesis have been addressed with my Research Faculty Advisor prior to the collection of any data used in this final thesis submission. This project did not require approval from the Texas A&M University Research Compliance & Biosafety office. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... -

Summer 2019 NEWSLETTER

CONTACT For more information, please contact the YIVO LETTER FROM Development Department: 212.294.6156 THE DIRECTOR DONATE ONLINE | vilnacollections.yivo.org/Donate The rise of antisemitism today through- These materials provide insight about the age-old disease out the world has many faces and of antisemitism and irrefutable evidence of its devastating disguises. Anti-Zionism, age-old stereo- consequences, thereby countering the world of lies, mis- types, the medieval blood libel fused conceptions, and hatred upon which antisemitism thrives. with accusations of world domination In the coming months, YIVO will develop new online edu- contained in The Protocols of the Elders cational and public programs, which use these precious of Zion, Holocaust Denial and the myth materials that both connect us to our past and help us of what today is called, Zydokomuna (Jew-communism) is shape our future. now prevalent throughout Eastern Europe and the United States. One of the root causes underpinning antisemitism Now is your opportunity to help us in our vital educational is pervasive historical ignorance. YIVO is uniquely placed mission by supporting our fundraising effort to raise $1 to address this ignorance. By making YIVO’s collections million to complete this historic project. available to the world for the first time through the Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections project, YIVO allows scholars, individuals, and institutions to confront myths, Jonathan Brent slanders, and stereotypes with robust historical evidence. Executive Director & CEO LOCATED IN THE CENTER FOR JEWISH HISTORY 15 West 16th Street New York, NY 10011-6301 yivo.org · 212.246.6080 Summer 2019 NEWSLETTER DIGITIZATION PROGRESS THROUGH About the Project JUNE 1, 2019 “THESE MATERIALS ARE HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS” During World War II, the Nazis looted The Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Online OVER 2.8 MILLION PAGES DIGITIZED YIVO’s archive and library, along with Collections project, launched in 2015, is other Jewish libraries in Vilnius, Lithua- a $7 million, international landmark dig- nia. -

The History of Blood Libel

Transcript for: The Power of a Lie: The History of Blood Libel Hatreds are rooted in stereotypes and myths. The lies persist despite heroic efforts to set the record straight. We are going to examine one of the most powerful and pernicious of those lies, the Blood Libel. It is false claim that Jews engage in ritual murder—that is, religiously sanctioned murder. It has been traced England in the 12 th century. 1. Church Photo and/or 2. Blinded Synagogue The 1100s were a time when many Christians were outraged that Jews refused to convert to Christianity. They saw the Jews’ refusal as a willful and obstinate denial of what they perceived as “God’s truth.” They expressed their anger in words and images that dehumanized and demonized Jews. It was in this charged atmosphere that some Christians began to accuse Jews of ritual murder. The accusation came at a time when life was precarious in Europe. And, as in other times of great fear and anxiety, many people found it all too easy to blame “them”—the people who are not like “us”—for every tragedy, every hardship, every loss. 3. Blood Libels Map 1144-1500, base map appears German Empire, France and England and then zooms into England and Norwich with first appearance of blood libel in 1144 (about 12 seconds total). The blood libel grew out of an incident that took place in Norwich, England, in 1144. On Good Friday, a woodsman discovered the body of a missing child in a forest near his home. The man claimed that young William’s death had to be the work of Jews, because no Christian would have murdered a child so brutally.