Post-Holocaust Pogroms in Hungary and in Poland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hungarian Historical Review 2, No

Hungarian Historical Review 2, no. 3 (2013): 566–604 A Pogrom in Hungary, 1946 Péter Apor the 1946 Kielce pogrom in Poland or a debate in the mid-1990s about the postwar beatings of Jews in the Hungarian countryside. For many historians The Lost Deportations and the Lost People the pogroms are explained by social and economic circumstances, in particular of Kunmadaras: A Pogrom in Hungary, 1946 the general privation and widespread social discontent that accompanied it, which was abused by various malicious political ideologies for their own purposes.1 Apparently, such cases prove the survival of prewar fascist and Nazi The subject of this article is one of the scandals of postwar Hungarian politics and racist propaganda and serve as ex post facto evidence for the complicity of society: the anti-Semitic pogrom that took place on May 21, 1946 in the village of local societies in the deportation of Jews initiated and coordinated by German Kunmadaras. The Kunmadaras riot was part of a series of anti-Jewish atrocities authorities.2 Other historians argue that while the impact of Nazi anti-Semitism that broke out in the summer of 1946 in the Hungarian countryside. These events, was relevant, postwar domestic Communist parties played a more instrumental however, were comparable with similar violence against surviving and returning Jewish communities in East Central Europe, particularly in Poland and Slovakia. The scholarly role in the pogroms, as they manipulated and abused anti-Semitic sentiments 3 literature so far has typically understood these events as the outcome of social discontent to legitimize their own dictatorial attempts. -

Act Cciii of 2011 on the Elections of Members Of

Strasbourg, 15 March 2012 CDL-REF(2012)003 Opinion No. 662 / 2012 Engl. only EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) ACT CCIII OF 2011 ON THE ELECTIONS OF MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT OF HUNGARY This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-REF(2012)003 - 2 - The Parliament - relying on Hungary’s legislative traditions based on popular representation; - guaranteeing that in Hungary the source of public power shall be the people, which shall pri- marily exercise its power through its elected representatives in elections which shall ensure the free expression of the will of voters; - ensuring the right of voters to universal and equal suffrage as well as to direct and secret bal- lot; - considering that political parties shall contribute to creating and expressing the will of the peo- ple; - recognising that the nationalities living in Hungary shall be constituent parts of the State and shall have the right ensured by the Fundamental Law to take part in the work of Parliament; - guaranteeing furthermore that Hungarian citizens living beyond the borders of Hungary shall be a part of the political community; in order to enforce the Fundamental Law, pursuant to Article XXIII, Subsections (1), (4) and (6), and to Article 2, Subsections (1) and (2) of the Fundamental Law, hereby passes the following Act on the substantive rules for the elections of Hungary’s Members of Parliament: 1. Interpretive provisions Section 1 For the purposes of this Act: Residence: the residence defined by the Act on the Registration of the Personal Data and Resi- dence of Citizens; in the case of citizens without residence, their current addresses. -

Tokarska-Bakir the Kraków Pogrom the Kraków Pogrom of 11 August

Tokarska-Bakir_The Kraków pogrom The Kraków Pogrom of 11 August 1945 against the Comparative Background 1. The aim of the conducted research/the research hypothesis The subject of the project is the analysis of the Kraków pogrom of August 1945 against the background of the preceding similar events in Poland (Rzeszów, June 1945) and abroad (Lviv, June 1945), as well as the Slovak and Hungarian pogroms at different times and places. The undertaking is a continuation of the research described in my book "Pod klątwą. Społeczny portret pogromu kieleckiego" (2018), in which I worked out a methodology of microhistorical analysis, allowing the composition of a pogrom crowd to be determined in a maximally objective manner. Thanks to the extensive biographical query it was possible to specify the composition of the forces of law and order of the Citizens' Militia (MO), the Internal Security Corps (KBW), and the Polish Army that were sent to suppress the Kielce pogrom, as well as to put forward hypotheses associated with the genesis of the event. The question which I will address in the presented project concerns the similarities and differences that exist between the pattern according to which the Kielce and Kraków pogroms developed. To what extent did the people who were within the structures of the forces of law and order, primarily communist militia, take part in it –those who murdered Jews during the war? Are the acts of anti-Semitic violence on the Polish, Ukrainian, and Slovak lands structurally similar or fundamentally different? What are the roles of the legend of blood (blood libel), the stereotype of Żydokomuna (Jewish communists), and demographical panic and panic connected with equal rights for Jews, which destabilised traditional social relations? In the framework of preparatory work I managed to initiate the studies on the Kraków pogrom in the IPN Archive (Institute of National Remembrance) and significantly advance the studies concerning the Ukrainian, Hungarian, and Slovak pogroms (the query was financed from the funds from the Marie Curie grant). -

JEGYZŐK ELÉRHETŐSÉGEI (Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok Megye)

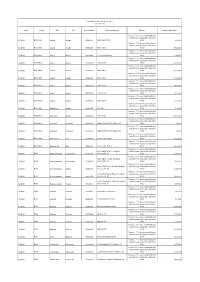

JEGYZ ŐK ELÉRHET ŐSÉGEI (Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok megye) 2017.08.23 Közös önkormányzat JEGYZ Ő Sz. Ir. sz. Település neve, címe Önkormányzat web-címe települései megnevezése Név Telefon Fax e-mail címe Abádszalók, Dr. Szabó István 1. 5241 Abádszalók, Deák F. u. 12. Abádszalóki Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal 59/355-224 59/535-120 [email protected] www.abadszalok.hu Tomajmonostora 2015.02.16-tól 2. 5142 Alattyán, Szent István tér 1. Tóth Ildikó 57/561-011 57/561-010 [email protected] www.alattyan.hu Berekfürd ő Kunmadarasi Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal Dr. Vincze Anita 3. 5309 Berekfürd ő, Berek tér 15. 59/519-003 59/519-002 [email protected] www.berekfurdo.hu Kunmadaras Berekfürd ői Kirendeltsége 2015.01.01-t ől Besenyszög Munkácsi György 56/487-002; 4. 5071 Besenyszög, Dózsa Gy. út 4. Besenyszögi Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal 56/487-178 [email protected] www.besenyszog.hu Szászberek címzetes f őjegyz ő 56/541-311 Cibakháza Török István [email protected]; 5. 5462 Cibakháza, Szabadság tér 5. Cibakházi Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal 56/477-001 56/577-032 www.cibakhaza.hu Tiszainoka 2016. július 1-t ől [email protected] Nagykör ű Nagykör űi Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal Szabó Szidónia 6. 5064 Csataszög, Szebb Élet u. 32. Csataszög 56/499-593 56/499-593 [email protected] www.csataszog.hu Csataszögi Kirendeltsége 2015.04.01-t ől Hunyadfalva Kunszentmárton Kunszentmártoni Közös Önkormányzati Hivatal 7. 5475 Csépa, Rákóczi u. 24. Dr. Hoffmann Zsolt 56/323-001 56/323-093 [email protected] www.csepa.hu Csépa Csépai Kirendeltsége [email protected] 8. -

List of Beneficiaries - FOP Priority Axis II

List of beneficiaries - FOP priority axis II. (1st June 2016) Region County Office Site Project identifier Name of beneficiary Measure Amount of support HUF Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1098982557 Szabó Róbert István fishery 7 268 549 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1099160437 Szabó József fishery 185 462 209 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1099219685 Czobor-Szabó Andrea fishery 12 491 533 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1220394092 Szabó József fishery 116 427 879 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1403233732 Szabó József fishery 121 133 947 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1534862007 Szabó József fishery 112 680 361 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1551073172 Szabó József fishery 14 565 813 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1697255443 Szabó József fishery 48 224 816 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Akasztó Akasztó 1750982217 Szabó József fishery 21 641 331 Measure 2.1. To ensure sustainability and competitiveness ofaquaculture and inland Dél-Alföld Bács-Kiskun Dunatetétlen Akasztó 1624017586 Turu János fishery 7 153 285 Measure 2.1. -

A Római Köztársaság Válsága II

J U R A A Pécsi Tudományegyetem Állam- és Jogtudományi Karának tudományos lapja A tartalomból STUDIUM ANDRÁSSY GYÖRGY: A szlovák államnyelvtörvény módosítása és az emberi jogok ANDRZEJ BISZTYGA: Poland on the way to the accession to eurozone. Constitutional aspects of the issue IMRE GARACZI: Von der Weltkrise zur Tradition HADI NIKOLETT: Fogyatékosság – nyelvi jogok – jelnyelv HERGER CSABÁNÉ: Egyházi modernizáció Franciaországban 1789-től 1905-ig ANDRÁS KECSKÉS: The Legal Theory of Stakeholder Protection KOCSIS MIKLÓS – KUCSERA TAMÁS GERGELY: A magyarországi doktori képzés állapota – interdiszciplináris megközelítésben MADARÁSZNÉ IFJU BERNADETT: A családtámogatási ellátások ANDRÁS LÁSZLÓ PAP: Ethno-racial profiling and discrimination in the criminal justice system: notes on current anti-terrorist legislation and law enforcement measures PÓKECZ KOVÁCS ATTILA: A római köztársaság válsága II. (i. e. 133–44) SÁNDOR JUDIT: Biobankok: Egy sikeres fikció a tudomány szolgálatában? VOGL MÁRK: A Szlovák Köztársaság államnyelvtörvénye a 2009. évi módosítások után YA NAN ZHANG: An overview and Evaluation of Civil Judgment Enforcement System in the People’s Republic of China COLLOQUIUM MÁTÉ JULESZ: The Collectivization of the Individuals’ Right to a Healthy Environment SOMFAI BALÁZS: A Gyermek Jogairól szóló Egyezmény egyes rendelkezései a hazai jogszabályokban VÁRSZEGI ZSÓFIA MÁRIA: Szabályrendelet-alkotás Baranya vármegyében 1867 és 1886 között FORUM KUN TIBOR: Világméretű korrupció az oktatásban? PETRÉTEI KRISTÓF: Gondolatok az országgyűlési képviselők 2010. évi általános választásának időpontjáról SOMFAI BALÁZS – HARMATH GABRIELLA: „Diákok a gyermekekért” gyermekjogi program SZABÓ GÁBOR: Rawls igazságosság-elmélete és kritikái VARGA KÁROLY: Ibükosz darvai a hazai igazságszolgáltatásban ZLINSZKY JÁNOS: Észrevételek a magánjog új törvénykönyvéhez AD HOC ÁDÁM ANTAL: In memoriam Herczegh Géza CSÁSZÁR KINGA: „Symbols and Ceremonies in the European Legal History”. -

The Libro Verde: Blood Fictions from Early Modern Spain

INFORMATION TO USERS The negative microfilm of this dissertation was prepared and inspected by the school granting the degree. We are using this film without further inspection or change. If there are any questions about the content, please write directly to the school. The quality of this reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original material The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When it is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to indicate this. 3. Oversize materials (maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sec tioning the original, beginning at the upper left hand comer and continu ing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Dissertation Information Service A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 9731534 Copyright 1997 by Beusterien, John L. All rights reserved. UMI Microform 9731534 Copyright 1997, by UMI Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Titic 17, United States Code. UMI 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, MI 48103 Reproduced with permission -

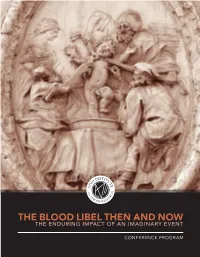

Read the Conference Program

COVER: Stone medallion with the purported martyrdom scene of Simonino di Trento. Palazzo Salvadori, Trent, Italy. Photo by Andreas Caranti. Via Wikimedia Commons. YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH PRESENTS CONFERENCE OCTOBER 9, 2016 CO-SPONSORED BY 1 INCE ITS FABRICATION IN THE MIDDLE AGES, the accusation that Jews Skidnapped, tortured and killed Christian children in mockery of Christ and the Crucifixion, or for the use of their blood, has been the basis for some of the most hateful examples of organized antisemitism. The blood libel has inspired expulsions and murder of Jews, tortures and forced mass conversions, and has served as an ines- capable focal point for wider strains of anti-Jewish sentiment that permeate learned and popular discourse, social and political thought, and cultural media. In light of contemporary manifestations of antisemitism around the world it is appropriate to re-examine the enduring history, the wide dissemination, and the persistent life of a historical and cultural myth—a bald lie—intended to demonize the Jewish people. This conference explores the impact of the blood libel over the centuries in a wide variety of geographic regions. It focuses on cultural memory: how cultural memory was created, elaborated, and transmitted even when based on no actual event. Scholars have treated the blood libel within their own areas of expertise—as medieval myth, early modern financial incentive, racial construct, modern catalyst for pogroms and the expulsion of Jews, and political scare tactic—but rarely have there been opportunities to discuss such subjects across chronological and disciplinary borders. We will look at the blood libel as historical phenomenon, legal justification, economic mechanism, and visual and literary trope with ongoing political repercussions. -

No Haven for the Oppressed

No Haven for the Oppressed NO HAVEN for the Oppressed United States Policy Toward Jewish Refugees, 1938-1945 by Saul S. Friedman YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY Wayne State University Press Detroit 1973 Copyright © 1973 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48202. All material in this work, except as identified below, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/. Excerpts from Arthur Miller’s Incident at Vichy formerly copyrighted © 1964 to Penguin Publishing Group now copyrighted to Penguin Random House. All material not licensed under a Creative Commons license is all rights reserved. Permission must be obtained from the copyright owner to use this material. Published simultaneously in Canada by the Copp Clark Publishing Company 517 Wellington Street, West Toronto 2B, Canada. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Friedman, Saul S 1937– No haven for the oppressed. Originally presented as the author’s thesis, Ohio State University. Includes bibliographical references. 1. Refugees, Jewish. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945) 3. United States— Emigration and immigration. 4. Jews in the United States—Political and social conditions. I. Title. D810.J4F75 1973 940.53’159 72-2271 ISBN 978-0-8143-4373-9 (paperback); 978-0-8143-4374-6 (ebook) Publication of this book was assisted by the American Council of Learned Societies under a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The publication of this volume in a freely accessible digital format has been made possible by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Mellon Foundation through their Humanities Open Book Program. -

Jewish Mysticism, Ritual Murder, and the Trial of Mendel Beilis

Swarthmore College Works History Faculty Works History 2015 Connecting The Dots: Jewish Mysticism, Ritual Murder, And The Trial Of Mendel Beilis Robert Weinberg Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-history Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Robert Weinberg. (2015). "Connecting The Dots: Jewish Mysticism, Ritual Murder, And The Trial Of Mendel Beilis". Word And Image In Russian History: Essays In Honor Of Gary Marker. 238-252. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-history/464 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Connecting the Dots: Jewish Mysticism, Ritual Murder, and the Trial of Mendel Beilis Robert Weinberg (Swarthmore College) he prosecution of Mendel Beilis for the murder of thirteen-year-old TAndrei Iushchinskii in Kiev a century ago is perhaps the most publi- cized instance of blood libel since the torture and execution of Jews accused of ritually murdering the infant Simon of Trent in 1475. By the time of the trial in the fall of 1913, the Beilis case had become an inter- national cause célèbre. Like the trials of Alfred Dreyfus in the 1890s and the outcry that accompanied the Damascus Affair in the 1840s, the arrest, incarceration, and trial of Beilis aroused public criticism of Russia’s treatment of Jews and inspired opponents of the autocracy at home and abroad to launch a campaign to condemn the trial. -

Poland Study Guide Poland Study Guide

Poland Study Guide POLAND STUDY GUIDE POLAND STUDY GUIDE Table of Contents Why Poland? In 1939, following a nonaggression agreement between the Germany and the Soviet Union known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Poland was again divided. That September, Why Poland Germany attacked Poland and conquered the western and central parts of Poland while the Page 3 Soviets took over the east. Part of Poland was directly annexed and governed as if it were Germany (that area would later include the infamous Nazi concentration camp Auschwitz- Birkenau). The remaining Polish territory, the “General Government,” was overseen by Hans Frank, and included many areas with large Jewish populations. For Nazi leadership, Map of Territories Annexed by Third Reich the occupation was an extension of the Nazi racial war and Poland was to be colonized. Page 4 Polish citizens were resettled, and Poles who the Nazis deemed to be a threat were arrested and shot. Polish priests and professors were shot. According to historian Richard Evans, “If the Poles were second-class citizens in the General Government, then the Jews scarcely Map of Concentration Camps in Poland qualified as human beings at all in the eyes of the German occupiers.” Jews were subject to humiliation and brutal violence as their property was destroyed or Page 5 looted. They were concentrated in ghettos or sent to work as slave laborers. But the large- scale systematic murder of Jews did not start until June 1941, when the Germans broke 2 the nonaggression pact with the Soviets, invaded the Soviet-held part of Poland, and sent 3 Chronology of the Holocaust special mobile units (the Einsatzgruppen) behind the fighting units to kill the Jews in nearby forests or pits. -

SAPARD REVIEW in Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Poland and Romania

SAPARD REVIEW in Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Poland and Romania IMPACT ANALYSIS OF THE AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT APRIL 2005 SAPARD REVIEW 2 COMPARATIVE STUDY ON THE SAPARD PROGRAMME - SEVEN POINTS OF VIEW SAPARD REVIEW IN BULGARIA, CZECH REPUBLIC, ESTONIA, HUNGARY, LATVIA, POLAND AND ROMANIA Impact analysis of the agriculture and rural development REPORT ON THE EFFECTIVENESS AND RELEVANCY OF INVESTMENT ACTIVITIES UNDER SAPARD IN BULGARIA IN ITS ROLE AS A PRE-ACCESSION FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE INSTRUMENT Miroslava Georgieva, Director of "Rural Development and Investments" Directorate Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Bulgaria NATIONAL REVIEW ON THE SAPARD PROGRAMME IN THE CZECH REPUBLIC Petra Cerna, IUCN - The International Union for Nature Conservation Regional Office for Europe, European Union Liaison Unit, Belgium SAPARD IN ESTONIA Doris Matteus, chief specialist, Ministry of Agriculture of Estonia, market development bureau, Estonia, www.praxis.ee PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTING THE SAPARD PROGRAMME IN HUNGARY Katalin Kovacs, Researcher Centre for Regional Studies, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Hungary, www.ceu.hu SAPARD IN LATVIA Juris Hazners, Project Manager Agricultural Marketing Promotion Center Latvian State Institute of Agrarian Economics, Latvia NATIONAL REVIEW OF SAPARD PRE-ACCESSION ASSISTANCE IMPACT ON NATIONAL AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT IN POLAND Tomasz Grosse, Head of the project Institute of Public Affairs, Poland, www.isp.org.pl NATIONAL REVIEW ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SAPARD PROGRAMME