Naslov 75 1.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S-GRA3 Regional Employment Pact

Rural-Urban Outlooks: Unlocking Synergies (ROBUST) ROBUST receives funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 727988.* October 2018 Federal Institute for Mountainous and Less-Favoured Areas Theresia Oedl-Wieser, Thomas Dax [email protected] Snapshot: Expressions of Urban – Peri-Urban – Rural Relationships Regional Employment Pact of the Metropolitan Area of Styria Metropolitan Area of Styria, Austria 1. Brief Description Territorial Employment Pacts (TEPs) are contracted partnerships to better link employment policy with other policies in order to improve the employment situation at the regional and local level. The TEPs were piloted in regional development policy of the EU in the late 1990s and had, due to its integrative approach and place-based strategy, a particular effect on (rural) territories. The support was provided within the framework of the Structural Funds Programme through the European Social Funds (ESF). Since 2001 TEPs have been main- streamed and established in all nine Austrian provinces. Additionally, some partnerships were set up at a sub-provincial level, the so-called “regional level” (e.g. in the provinces of Styria and Upper Austria). The “Regional Employment Pact of the Metropolitan Area of Styria” (REPMAS) was established in 2000 and was set up as a regional platform to gather all interested stakeholders in the fields of labour market, economic policy and regional development. It had the function of an advisory board of experts. The closer collaboration between representatives of these policy fields in the regional context (Public Employment Service Austria, Chamber of Labour, Federation of Austrian Industries, Trade Unions, Austrian Economic Chamber and political interest groups) faced the challenging objectives to strive for a better adaptation of policies to local circumstances, needs and opportunities in the field of employment. -

Wärmeversorgung Graz Statusbericht 2019

Wärmeversorgung Graz 2020/2030 Wärmebereitstellung für die fernwärmeversorgten Objekte im Großraum Graz Statusbericht 2019 IMPRESSUM Energie Graz GmbH & Co KG Schönaugürtel 65, 8010 Graz │Tel.: 0316 8057-1600 www.energie-graz.at Stadt Graz│Umweltamt Schmiedgasse 26, 8011 Graz │Tel.: 0316 872-4302 www.umwelt.graz.at Energie Steiermark Wärme GmbH Leonhardgürtel 10, 8010 Graz │Tel.: 0316 9000-51100 www.e-steiermark.com Holding Graz - Kommunale Dienstleistungen GmbH Andreas Hofer Platz 15, 8010 Graz │Tel.: 0316 887 www.holding-graz.at Amt der Steiermärkischen Landesregierung A 15 - Fachabteilung Energie und Wohnbau Referat Energietechnik und Klimaschutz Landhausgasse 7, 8010 Graz │Tel.: 0316 877-2201 www.verwaltung.steiermark.at Fachliche und organisatorische Begleitung: Grazer Energieagentur Ges.m.b.H. Kaiserfeldgasse 13/I, 8010 Graz │Tel.: 0316 811848 www.grazer-ea.at AUTOREN: Bakk. Martin Diewald (Holding Graz - Kommunale Dienstleistungen GmbH) DI Wolfgang Götzhaber (Stadt Graz│Umweltamt) DI Ernst Meißner (Grazer Energieagentur Ges.m.b.H.) DI Gerald Moravi (Energie Steiermark Wärme GmbH) DI Dr. Werner Prutsch (Stadt Graz│Umweltamt), Projektleitung Dipl.-WI (FH) Peter Schlemmer (Energie Graz GmbH & Co KG) DI Robert Schmied (Grazer Energieagentur Ges.m.b.H.) Dipl.-HTL-Ing. Erich Slivniker (Energie Graz GmbH & Co KG) DI Dieter Thyr (Amt der Steiermärkischen Landesregierung) DI Martin Zimmel (Energie Steiermark Wärme GmbH) HERAUSGEBER/MEDIENINHABER: Grazer Energieagentur Ges.m.b.H HERSTELLER UND VERLAGSORT: Medienfabrik Graz GmbH, Graz FOTOS: iStock©Vasyl90 (S.1), Energie Graz (S.11, S.13, S.25, S.26, S.27, S.29), Energie Steiermark (S.11, S.20, S.22, S.23, S.24, S.30, S.31), Stadt Graz Stadtvermessungsamt (S.11), Stadt Graz/Foto Fischer (S.11, S.14, S.16), Bioenergie Fernwärme BWS (S.11, S.15), Energie Graz WDS (S.11, S.17, S.28), SOLID (S.11), Stadt Graz│Umweltamt (S.11, S.19, S.21, S.33), Stadt Graz Tourismus - Harry Schiff er (S. -

Sommerausgabe 11. Ausgabe 07/2020 Teil 1

Amtliche Mitteilung Zugestellt durch Post.at GemeindenachrichtenGemeindenachrichten derder MARKTGEMEINDEMARKTGEMEINDE SANKTSANKT MAREINMAREIN BEIBEI GRAZGRAZ 11. Ausgabe 07/2020 Lilienbad St. Marein bei Graz Wir wünschen allen einen schönen Sommer und erholsame Urlaubstage! 8323 Markt 25 · Tel.: 03119/2227 · [email protected] · www.st-marein-graz.gv.at MARKTGEMEINDE SANKT MAREIN BEI GRAZ Liebe Gemeindebürgerinnen! Liebe Gemeindebürger! In den letzten Monaten sind wir mit in mein Team möchte ich mich sehr herzlich bedanken! neuen Begrifflichkeiten konfrontiert Es war für mich eine besondere Freude in den letzten fünf worden, wie „shut down“, „lock Jahren für die „neue“ Marktgemeinde St. Marein bei Graz down“, „homeschooling“. Zudem zu arbeiten. Es begann im Jahr 2015 mit der besonderen arbeiteten viele von uns im „home- Herausforderung, die Gemeindefusion der drei Altgemein- office“ und der Rest des täglichen Lebens musste neu geord- den umzusetzen. Die größten Veränderungen betrafen die net werden. Die Coronakrise hat unser Leben ordentlich auf Gemeindeverwaltung, weiters konnten einige Neubau- und den Kopf gestellt. Selbst die Gemeinderatswahlen mussten Sanierungsprojekte realisiert und umgesetzt werden. Auch unterbrochen bzw. verschoben werden. Trotz all dieser Her- der Fuhrpark wurde ausgebaut und erneuert, die Erhaltung ausforderungen und Veränderungen in unserem alltäglichen des Straßennetzes und die schrittweise Erneuerung der Leben, hört man immer wieder, dass viele auch etwas Positi- Beleuchtung sind Themen, die uns ständig begleiten. In ves aus dieser Zeit mitnehmen konnten. Wir schätzen, dass der Wasserversorgung konnte eine digitale Überwachung das heimische Gasthaus uns das Mittagessen liefern konnte. installiert werden und der digitale Leitungskataster steht Wir schätzen, dass die Nahversorgung in unserer Gemeinde nun auch im letzten Ortsteil vor der Fertigstellung. -

Essencemembers of the Cluster Human.Technology.Styria

18 essencemembers of the cluster human.technology.styria. 1 legend Manufacturers Suppliers M MedTech M MedTech P Pharma & BioTech P Pharma & BioTech Research & Education U Universities & Universities of Applied Sciences N Non-university Organisations Services C Consultants H Health Care Providers I Information & Communication Technologies T Technical Services O Other Styria. Micro-enterprises (up to 9 employees, turnover ≤ EUR 2 m ) Where the future Small enterprises (10 to 49 employees, turnover ≤ EUR 10 m ) is taking place. Large enterprises (from 50 employees, turnover > EUR 50 m ) cluster partner Statements page page ams AG ____________________________________13 KML vision OG ______________________________50 4a engineering GmbH ________________________42 Know-Center GmbH _________________________38 Styria is Austria‘s number one state Our info brochure “essence“, lists AAL Austria ________________________________42 Körbler GmbH ______________________________50 AIT Austrian Institute of Technology GmbH ______35 KRATSCHMANN & Partner ____________________27 for innovation and research, and also precisely 117 members, who are Albert Schweitzer Institut für Geriatrie und Lorenz Consult Ziviltechniker GmbH ____________50 Gerontologie ________________________________42 Lugitsch-Strasser GmbH ______________________18 tops the European rankings for re- “essential“ in the most literal sen- Antemo GmbH ______________________________13 M27 FEDAS Management und search and development. This is all se of the word for the research and APUS Software -

CG37(2019)24 7 July 2020

ACTIVITY REPORT (Mid-October 2019 – June 2020) s part of its monitoring of local and regional democracy in Europe, the Congress maintains a regular dialogue with A member states of the Council of Europe. The Committee of Ministers, which includes the 47 Foreign Ministers of these states, the Conference of Ministers responsible for local and regional authorities, as well as its Steering Committees are partners in this regard. Several times a year, the President and the Secretary General of the Congress provide the representatives of the 47 member states in the Committee of Ministers with a record of its activities. www.coe.int/congress/fr PREMS 082820 [email protected] ENG The Council of Europe is the continent’s leading human rights organisation. It comprises 47 member states, including all Communication by the Secretary General members of the European Union. The Congress of Local and of the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities Regional Authorities is an institution of the Council of Europe, www.coe.int responsible for strengthening local and regional democracy 1380bis meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies in its 47 member states. Composed of two chambers – the Chamber of Local Authorities and the Chamber of Regions – 8 July 2020 and three committees, it brings together 648 elected officials representing more than 150 000 local and regional authorities. Activity report of the Congress (October 2019 – June 2020) CG37(2019)24 7 July 2020 Activity Report of the Congress (October 2019 – June 2020) Communication by the Secretary General of the Congress at the 1380bis meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies 8 July 2020 Layout: Congress of Local and Regional Authorities Print: Council of Europe Edition: July 2020 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Communication by Andreas KIEFER, Acting Secretary General of the Congress ........ -

AIMS Handbook Updated April 2018

AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF MUSICAL STUDIES AIMS in Graz, Austria since 1970 AIMS Handbook updated April 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1 Preparing for the AIMS in GRAZ Experience 1.1 German 1.2 Health Matters 1.3 Health Care 1.4 Medical Insurance 1.5 Prescription Drugs 1.6 Special Diets 1.7 Passports 1.8 Visas 1.9 Transportation to Graz 1.9.1 Arrival in Graz 1.9.2 General Flight Info 1.10 Travel Insurance 1.10.1 Baggage Insurance 1.10.2 Flight Cancellation and Travel Insurance 1.10.3 Medical Insurance While Abroad 1.11 U.S. Customs 1.11.1 Contraband 1.11.2 Declarations 1.12 What to Bring to Graz 1.12.1 Electricity, Adapter Plugs & 220 volt Appliances 1.12.2 Clothing and the Weather in Graz 1.12.3 Necessities and Helpful Items 1.13 Helpful Reminders 1.14 Instrument Travel 1.15 Labeling your Luggage 1.16 Money for Food and incidental Expenses 1.17 Changing Money (also see section 4.1) Debit cards, Credit cards, Cash advances, Personal checks, Traveler’s checks, Cash 1.18 Music and Repertoire 1.19 Photos 1.20 Your AIMS Address 1.21 Telephones 1.22 Setting Realistic Goals for a Profitable Summer Section 2 Arriving and Getting Settled at the Studentenheim and in Graz 2.1 Room/Key Deposit 2.2 Changing Money 2.3 Streetcar/Bus Tickets 2.4 Photocopy of Passport 2.5 Late Arrivals 2.6 Jet Lag 2.7 Time Difference between Graz and the U.S. Section 3 Living in the Studentenheim 3.1 Studentenheim Layout 3.2 Practice Rooms 3.3 Sleeping Rooms 3.3.1 Contents 3.3.2 Electricity 3.3.3 Security 3.3.4 Your Responsibilities 3.4 Breakfast 3.5 Overnight Guests 3.6 -

Gemeindeleben Aktuelles Aus Der Marktgemeinde Raaba-Grambach

Amtliche Mitteilung Ausgabe 2/2021 gemeindeLeben Aktuelles aus der Marktgemeinde raaba-grambach Herausnehmen: „Vierseitiges Special zum DEM LEBEN öffentlichen MEHR GEBEN! Verkehr“ wohnen_wirtschaft_wohlbefinden Wir wünschen Ihnen, liebe Gemeindebürgerinnen, Gemeindebürger und liebe Jugend, ein frohes Osterfest im Kreise Ihrer Familie. Ihr/Euer Bürgermeister Karl Mayrhold, die Gemeindevertretung und die Bediensteten der Marktgemeinde Raaba-Grambach Termine Gutschein-Aktion Regional Speisensegnungen verlängert einkaufen Seite 5 Seite 8 Seite 9 Inhalte BürgerInnenservice ...............................................................................................5 bis 9 Termine der Speisesegnung, Neue Mitarbeiterin im Bauamt, Digitales Amt, Information vom Wasserverband Grazerfeld Südost, Gemeinde Raaba-Grambach auch auf Facebook und Instagram, Grünschnittabholung, Osterjause regional einkaufen… Aktuelles aus der Gemeinde ....................................................................10 bis 23 Eröffnung fünfte Krippengruppe, Raaba-Grambach-Gutscheinaktion verlängert, Raaba-Grambach und Umlandgemeinden helfen bei Behebung von Erdbebenschäden in Kroatien, Frühjahrsputz Raaba-Grambach, Aktuelles und Rückblick der Klima- und Energiemodellregion GU Süd, Öffentlicher Verkehr in und um Raaba-Grambach, Neues aus dem FamilienZelt… Special öffentlicher Verkehr im Bund – zum Herausnehmen Wirtschaft .................................................................................................................................. 24 Unternehmen -

An Urb a Ct Ii Pr Oject

CityRegions in progress Arezzo ie Stadt Arezzo liegt zwischen dem Als Partner des “City.Region.Net” nimmt tor, the tertiary sector, together with as- DApennin und den Hügeln der Süd- Arezzo teil an der Ausarbeitung und Ent- sociations and cooperatives, is important toskana. Arezzo ist die Hauptstadt und wicklung von Richtlinien (Infrastruktur, for the city. Nowadays the city is expe- das Verwaltungs- und Wirtschaftszen- Wirtschaft, Versorgungsbetriebe und so- riencing a period of decline due to a lack trum der gleichnamigen Provinz. Es gibt ziale Einrichtungen betreffend), sowohl of investment, globalization of produc- eine deutliche räumliche Trennung zwi- im Rahmen des gegenwärtigen polyzen- tion and the internationalization of trade. schen Arezzo und Siena, da die dazwi- trischen regionalen Systems als auch im Products made of gold are no longer schen liegende Landschaft wenig bevöl- Rahmen des neuen größeren Gebiets, das made in the city and it is facing the need kert und mehr landwirtschaftlich genutzt Arezzo, Siena und Grosseto umfasst. to reposition itself strategically. ist. Regarding “City.Region.Net”, Arezzo Die moderne Geschäftsidentität von he town of Arezzo is located between takes part in working out and develop- Arezzo basiert auf starkem Wirtschafts- Tthe fertile depression in the Appen- ing major territorial policies (relating to wachstum aus der Produktion und aus nine Mountains and the beautiful hills of infrastructure, the economy, to public Bezirken, deren Schwerpunkt die Herstel- southern Tuscany. Arezzo is the adminis- utilities and social facilities) in the con- lung von Schmuck und Bekleidung ist. Zu- trative and economic capital of a large text of the regional urban polycentric sätzlich zur Industrie ist der Dienstlei- province of the same name. -

Bundesgesetzblatt Für Die Republik Österreich

1 von 3 BUNDESGESETZBLATT FÜR DIE REPUBLIK ÖSTERREICH Jahrgang 2006 Ausgegeben am 2. März 2006 Teil II 98. Verordnung: 2. Änderung der Wildvogel-Geflügelpestverordnung 2006 98. Verordnung der Bundesministerin für Gesundheit und Frauen zur 2. Änderung der Verordnung über Schutzmaßnahmen wegen Verdachtsfällen von Geflügelpest bei Wildvögeln (2. Änderung der Wildvogel-Geflügelpestverordnung 2006) Gemäß § 1 Abs. 5 und 6 sowie der §§ 2 und 2c des Tierseuchengesetzes RGBl. Nr. 177/1909, zuletzt geändert durch das Bundesgesetz BGBl. I Nr. 67/2005, wird verordnet: § 1. Die Anhänge der Verordnung der Bundesministerin für Gesundheit und Frauen über Schutz- maßnahmen wegen Verdachtsfällen von Geflügelpest bei Wildvögeln (Wildvogel- Geflügelpestverordnung 2006), BGBl. II Nr. 80/2006, zuletzt geändert durch die Verordnung BGBl. II Nr. 88/2006, werden durch die Anhänge zu dieser Verordnung ersetzt. § 2. Diese Verordnung tritt mit Ablauf des 2. März 2006 in Kraft. Rauch-Kallat Anhang A Schutzzonen Die Schutzzone 1 umfasst ab 18. Februar 2006: In der Steiermark: die Gemeinden Mellach, Weitendorf und Werndorf, sowie in der Gemeinde Stocking die Katastralge- meinde Sukdull, in der Gemeinde Wildon die Katastralgemeinde Wildon und in der Gemeinde Wund- schuh die Katastralgemeinde Wundschuh. Die Schutzzone 2 umfasst ab 18. Februar 2006: In der Steiermark: die Gemeinden Kaibing, St. Johann bei Herberstein, Siegersdorf bei Herberstein, Hirnsdorf und Kulm bei Weiz, sowie in der Gemeinde Stubenberg die Katastralgemeinden Vockenberg, Freienberg und Buchberg, in der Gemeinde Tiefenbach bei Kaindorf die Katastralgemeinde Untertiefenbach und in der Gemeinde Pischelsdorf in der Steiermark die Katastralgemeinde Romatschachen. Die Schutzzone 3 umfasst ab 18. Februar 2006: In Wien: den 21. und 22. Bezirk der Stadtgemeinde Wien. -

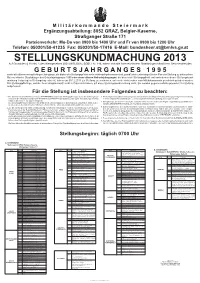

G E B U R T S J a H R G a N G E S 1 9

M i l i t ä r k o m m a n d o S t e i e r m a r k Ergänzungsabteilung: 8052 GRAZ, Belgier-Kaserne, Straßganger Straße 171 Parteienverkehr: Mo-Do von 0900 bis 1400 Uhr und Fr von 0900 bis 1200 Uhr Telefon: 050201/50-41235 Fax: 050201/50-17416 E-Mail: [email protected] STELLUNGSKUNDMACHUNG 2013 Auf Grund des § 18 Abs. 1 des Wehrgesetzes 2001 (WG 2001), BGBl. I Nr. 146, haben sich alle österreichischen Staatsbürger männlichen Geschlechtes des G E B U R T S J A H R G A N G E S 1 9 9 5 sowie alle älteren wehrpflichtigen Jahrgänge, die bisher der Stellungspflicht noch nicht nachgekommen sind, gemäß dem unten angeführten Plan der Stellung zu unterziehen. Österreichische Staatsbürger des Geburtsjahrganges 1995 oder eines älteren Geburtsjahrganges, bei denen die Stellungspflicht erst nach dem in dieser Stellungskund- machung festgelegten Stellungstag entsteht, haben am 09.12.2013 zur Stellung zu erscheinen, sofern sie nicht vorher vom Militärkommando persönlich geladen wurden. Für Stellungspflichtige, welche ihren Hauptwohnsitz nicht in Österreich haben, gilt diese Stellungskundmachung nicht. Sie werden gegebenenfalls gesondert zur Stellung aufgefordert. Für die Stellung ist insbesondere Folgendes zu beachten: 1. Für den Bereich des Militärkommandos STEIERMARK werden die Stellungspflichtigen durch die Stellungskom- 3. Bei Vorliegen besonders schwerwiegender Gründe besteht die Möglichkeit, dass Stellungspflichtige auf ihren Antrag missionen der Militärkommanden STEIERMARK und KÄRNTEN der Stellung unterzogen. Das Stellungsverfahren in einem anderen Bundesland oder zu einem anderen Termin der Stellung unterzogen werden. nimmt in der Regel 1 1/2 Tage in Anspruch. -

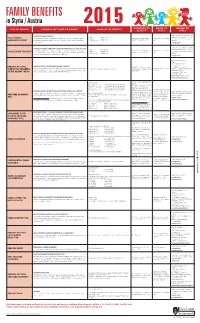

In Styria / Austria 2015 DURATION of WHEN to WHERE to TYPE of BENEFIT PERSONS ENTITLED to BENEFIT AMOUNT of BENEFIT BENEFIT APPLY APPLY

FAMILY BENEFITS in Styria / Austria 2015 DURATION OF WHEN TO WHERE TO TYPE OF BENEFIT PERSONS ENTITLED TO BENEFIT AMOUNT OF BENEFIT BENEFIT APPLY APPLY Apply to the local tax office; as part of the TAX RELIEF FOR SINGLE PARENTS 1 child: € 494 per year employee tax assessment or income tax SINGLE PARENT / Reviewed once a year providing all After the end of each calendar For taxpayers with a child who are NOT living in a partnership (= no more than 6 months a year in 2 children: € 669 per year return and/or accompanied by a separate requirements have been fulfilled. year. GUARDIAN TAX CREDIT a matrimonial or similar partnership). At least one child must be entitled to receive family allowance each further child: + € 220 per year application. during this period. www.bmf.gv.at Apply to the local tax office; as part of the TAX RELIEF FOR SINGLE EARNERS IN A FAMILY PARTNERSHIP WITH AT LEAST ONE CHILD 1 child: € 494 per year employee tax assessment or income tax Reviewed once a year providing all After the end of each calendar For taxpayers co-habiting as a couple for over 6 months a calendar year (either as a married couple or 2 children: € 669 per year return and/or accompanied by a separate SINGLE EARNER TAX CREDIT requirements have been fulfilled. year. in a non-marital relationship or as a registered partnership), who have an equally long claim to family each further child: + € 220 per year application. benefit and whose partner has a monthly income of € 6,000 or less. -

Life Science Directory Austria 2019

50.000 Euro aws Temporary Management Financing of complementary management expertise www.awsg.at/maz 1.000.000 Euro aws Seedfinancing Financing the start-up phase of life science companies www.seednancing.at 200.000 Euro aws PreSeed Financing the pre-start phase www.preseed.at We bring Life Sciences to Life 2980 www.lifescienceaustria.at 50.000 Euro 2019 aws Temporary Management Financing of complementary management expertise Directory 800.000 Euro aws Seedfinancing Financing the start-up phase of life science companies Life Sciences in Austria 200.000 Euro aws PreSeed Financing the Directory 2019 pre-start phase Life Sciences in Austria Austria in Sciences Life We bring Life Sciences to Life 978-3-928383-68-4 www.lifescienceaustria.at aws_bob lisa_anzeigen_A5_.indd 2 18.09.18 14:21 get your business started! aws best of biotech International Biotech & Medtech Business Plan Competition www.bestofbiotech.at aws_bob lisa_anzeigen_A5_.indd 1 18.09.18 14:20 Life Sciences in Austria Directory 2019 © BIOCOM AG, Berlin 2018 Life Sciences in Austria 2019 Editor: Simone Ding Publisher: BIOCOM AG, Lützowstr. 33-36, 10785 Berlin Tel. +49 (0)30 264 921 0 www.biocom.de, E-Mail: [email protected] Cover picture: BillionPhotos.com/fotolia.com Printed by: gugler GmbH, Melk, Austria This book is protected by copyright. All rights including those regarding translation, reprinting and reproduction reserved. No part of this book cove- red by the copyright hereon may be processed, reproduced, and proliferated in any form or by any means (graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or via information storage and retrieval systems, and the Internet).