Developing Sustainable and Flexible Rural–Urban Connectivity Through Complementary Mobility Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wärmeversorgung Graz Statusbericht 2019

Wärmeversorgung Graz 2020/2030 Wärmebereitstellung für die fernwärmeversorgten Objekte im Großraum Graz Statusbericht 2019 IMPRESSUM Energie Graz GmbH & Co KG Schönaugürtel 65, 8010 Graz │Tel.: 0316 8057-1600 www.energie-graz.at Stadt Graz│Umweltamt Schmiedgasse 26, 8011 Graz │Tel.: 0316 872-4302 www.umwelt.graz.at Energie Steiermark Wärme GmbH Leonhardgürtel 10, 8010 Graz │Tel.: 0316 9000-51100 www.e-steiermark.com Holding Graz - Kommunale Dienstleistungen GmbH Andreas Hofer Platz 15, 8010 Graz │Tel.: 0316 887 www.holding-graz.at Amt der Steiermärkischen Landesregierung A 15 - Fachabteilung Energie und Wohnbau Referat Energietechnik und Klimaschutz Landhausgasse 7, 8010 Graz │Tel.: 0316 877-2201 www.verwaltung.steiermark.at Fachliche und organisatorische Begleitung: Grazer Energieagentur Ges.m.b.H. Kaiserfeldgasse 13/I, 8010 Graz │Tel.: 0316 811848 www.grazer-ea.at AUTOREN: Bakk. Martin Diewald (Holding Graz - Kommunale Dienstleistungen GmbH) DI Wolfgang Götzhaber (Stadt Graz│Umweltamt) DI Ernst Meißner (Grazer Energieagentur Ges.m.b.H.) DI Gerald Moravi (Energie Steiermark Wärme GmbH) DI Dr. Werner Prutsch (Stadt Graz│Umweltamt), Projektleitung Dipl.-WI (FH) Peter Schlemmer (Energie Graz GmbH & Co KG) DI Robert Schmied (Grazer Energieagentur Ges.m.b.H.) Dipl.-HTL-Ing. Erich Slivniker (Energie Graz GmbH & Co KG) DI Dieter Thyr (Amt der Steiermärkischen Landesregierung) DI Martin Zimmel (Energie Steiermark Wärme GmbH) HERAUSGEBER/MEDIENINHABER: Grazer Energieagentur Ges.m.b.H HERSTELLER UND VERLAGSORT: Medienfabrik Graz GmbH, Graz FOTOS: iStock©Vasyl90 (S.1), Energie Graz (S.11, S.13, S.25, S.26, S.27, S.29), Energie Steiermark (S.11, S.20, S.22, S.23, S.24, S.30, S.31), Stadt Graz Stadtvermessungsamt (S.11), Stadt Graz/Foto Fischer (S.11, S.14, S.16), Bioenergie Fernwärme BWS (S.11, S.15), Energie Graz WDS (S.11, S.17, S.28), SOLID (S.11), Stadt Graz│Umweltamt (S.11, S.19, S.21, S.33), Stadt Graz Tourismus - Harry Schiff er (S. -

Sommerausgabe 11. Ausgabe 07/2020 Teil 1

Amtliche Mitteilung Zugestellt durch Post.at GemeindenachrichtenGemeindenachrichten derder MARKTGEMEINDEMARKTGEMEINDE SANKTSANKT MAREINMAREIN BEIBEI GRAZGRAZ 11. Ausgabe 07/2020 Lilienbad St. Marein bei Graz Wir wünschen allen einen schönen Sommer und erholsame Urlaubstage! 8323 Markt 25 · Tel.: 03119/2227 · [email protected] · www.st-marein-graz.gv.at MARKTGEMEINDE SANKT MAREIN BEI GRAZ Liebe Gemeindebürgerinnen! Liebe Gemeindebürger! In den letzten Monaten sind wir mit in mein Team möchte ich mich sehr herzlich bedanken! neuen Begrifflichkeiten konfrontiert Es war für mich eine besondere Freude in den letzten fünf worden, wie „shut down“, „lock Jahren für die „neue“ Marktgemeinde St. Marein bei Graz down“, „homeschooling“. Zudem zu arbeiten. Es begann im Jahr 2015 mit der besonderen arbeiteten viele von uns im „home- Herausforderung, die Gemeindefusion der drei Altgemein- office“ und der Rest des täglichen Lebens musste neu geord- den umzusetzen. Die größten Veränderungen betrafen die net werden. Die Coronakrise hat unser Leben ordentlich auf Gemeindeverwaltung, weiters konnten einige Neubau- und den Kopf gestellt. Selbst die Gemeinderatswahlen mussten Sanierungsprojekte realisiert und umgesetzt werden. Auch unterbrochen bzw. verschoben werden. Trotz all dieser Her- der Fuhrpark wurde ausgebaut und erneuert, die Erhaltung ausforderungen und Veränderungen in unserem alltäglichen des Straßennetzes und die schrittweise Erneuerung der Leben, hört man immer wieder, dass viele auch etwas Positi- Beleuchtung sind Themen, die uns ständig begleiten. In ves aus dieser Zeit mitnehmen konnten. Wir schätzen, dass der Wasserversorgung konnte eine digitale Überwachung das heimische Gasthaus uns das Mittagessen liefern konnte. installiert werden und der digitale Leitungskataster steht Wir schätzen, dass die Nahversorgung in unserer Gemeinde nun auch im letzten Ortsteil vor der Fertigstellung. -

Naslov 75 1.Qxd

Geografski vestnik 75-1, 2003, 41–58 Razprave RAZPRAVE THE RURAL-URBAN FRINGE: ACTUAL PROBLEMS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES AV TO R Walter Zsilincsar Naziv: dr., profesor Naslov: Institut für Geographie und Raumforschung, Universität Graz, Heinrichstrasse 36, A – 8010 Graz, Austria E-po{ta: [email protected] Telefon: +43 316 380 88 53 Faks: +43 316 380 88 53 UDK: 911.375(436.4) COBISS: 1.02 ABSTRACT The rural-urban fringe: actual problems and future perspectives The rural-urban fringe is undergoing remarkable structural, physiognomic and functional changes. Due to a significant drain of purchasing power from the urban core to the periphery new forms of suburban- ization are spreading. Large-scale shopping centres and malls, entertainment complexes, business and industrial parks have led not only to a serious competition between the city centres and the new suburban enterpris- es but also among various suburban communities themselves. The pull of demand for development areas and new transport facilities have caused prices for building land to rise dramatically thus pushing remain- ing agriculture and detached housing still further outside. These processes are discussed generally and by the example of the Graz Metropolitan Area. KEYWORDS rural-urban fringe, planning principles, urban sprawl, regional development program, shopping center, glob- alization, agriculture, residential development IZVLE^EK Obmestje: aktualni problemi in bodo~e perspektive Obmestje (mestno obrobje) je prostor velikih strukturnih, fiziognomskih in funkcijskih sprememb. Zara- di selitve nakupovalnih aktivnosti iz mestnega sredi{~a na obrobje se {irijo nove oblike suburbanizacije. Velika nakupovalna sredi{~a in nakupovalna sprehajali{~a, zabavi{~na sredi{~a ter poslovni in industrijski par- ki so poleg resnega tekmovanje med mestnimi sredi{~i in obmestnimi poslovnimi zdru`enji povzro~ili tudi tekmovanje med razli~nimi obmestnimi skupnostmi. -

Post-Communist Memory Culture and the Historiography of the Second World War and the Post-War Execution of Slovenian Collaborationists

Croatian Political Science Review, Vol. 55, No. 2, 2018, pp. 33-49 33 Original research article Received: 21 August 2017 DOI: 10.20901/pm.55.2.02 Post-Communist Memory Culture and the Historiography of the Second World War and the Post-War Execution of Slovenian Collaborationists OTO LUTHAR Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts Summary This paper aims to summarize the transformations in contemporary Slove- nia’s post-socialist memorial landscape as well as to provide an analysis of the historiographical representation of The Second World War in the Slovenian territory. The analysis focuses on the works of both Slovenian professional and amateur historiographical production, that address historic developments which took place during the Second World War and in its immediate aftermath from the perspective of the post-war withdrawal of the members of various military units (and their families) that collaborated with the occupiers during the Second World War. Keywords: Slovenes, Partisans, Home Guards, Historiography, Memory Introduction The debate on post-communist/post-socialist historical interpretation has become an inseparable part of the new politics of the past across Eastern and Southeastern Europe. In Slovenia, the once-vivid historiographical debate on the nature of histo- rical explanation has been ever since largely overshadowed by new attempts to mo- nopolize historical interpretation. The discussion, that has been led from the 1980s onwards, has brought forward new forms of historical representation which have once again given way to the politicized reinterpretation of the most disputed parts of the Second World War and the subsequent time of socialism. Like in some other parts of post-socialist Europe, the past has become a “morality drama” and a “pas- 34 Luthar, O., Post-Communist Memory Culture and the Historiography of the Second World War.. -

Portrait of the Regions – Slovenia Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities 2000 – VIII, 80 Pp

PORTRAIT OF THE REGIONS 13 17 KS-29-00-779-EN-C PORTRAIT OF THE REGIONS VOLUME 9 SLOVENIA VOLUME 9 SLOVENIA Price (excluding VAT) in Luxembourg: ECU 25,00 ISBN 92-828-9403-7 OFFICE FOR OFFICIAL PUBLICATIONS OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES EUROPEAN COMMISSION L-2985 Luxembourg ࢞ eurostat Statistical Office of the European Communities PORTRAIT OF THE REGIONS VOLUME 9 SLOVENIA EUROPEAN COMMISSION ࢞ I eurostat Statistical Office of the European Communities A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu.int). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2000 ISBN 92-828-9404-5 © European Communities, 2000 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Belgium II PORTRAIT OF THE REGIONS eurostat Foreword The accession discussions already underway with all ten of the Phare countries of Central and Eastern Europe have further boosted the demand for statistical data concerning them. At the same time, a growing appreciation of regional issues has raised interest in regional differences in each of these countries. This volume of the “Portrait of the Regions” series responds to this need and follows on in a tradition which has seen four volumes devoted to the current Member States, a fifth to Hungary, a sixth volume dedicated to the Czech Republic and Poland, a seventh to the Slovak Republic and the most recent volume covering the Baltic States, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Examining the 12 statistical regions of Slovenia, this ninth volume in the series has an almost identical structure to Volume 8, itself very similar to earlier publications. -

“(Slovene) Medieval History” in the Book's Subtitle Should Be

INTRODUCTION Th e phrase “(Slovene) medieval history” in the book’s subtitle should be understood in its geographical, not ethnic sense: it does not mean that the papers deal with the history of the Slovenes, but rather with historical developments and phenomena from the Middle Ages in the area that is today associated with (the Republic of) Slovenia. At the same time, we must be aware that even such a geographical defi nition can only be approximate and provisional: the contemporary frame- work of the state certainly should not limit our view or research when dealing with remote periods, when many political, linguistic, ethnical, and other borders diff ered essentially and the area had a diff erent struc- ture. Th e developments in the coastal towns of present-day Slovenia, for instance, cannot be adequately understood and described without knowledge and consideration of the conditions in the whole of Istria, the historical province that is today divided between Italy, Slovenia, and Croatia, or without giving due consideration to the roles played by the Byzantine, Frankish, or Venetian authorities in the peninsula. To quote another example, the situation is similar to that of Styria (or Carinthia, or Gorizia, etc.). Since 1918, that historical Land, formed in the 12th century, has been divided between two states, Austria and Slovenia (Yugoslavia) into Austrian and Slovene Styria, and the latter occupies about one third of the former Land. It is clear, then, that we can research and describe some chapters from its history only if we focus on Styria as a whole, regardless of its current borders; or, in other words, if we view it – and this is true of everything in history – as a variable historical category that cannot be treated outside the context of the period we are interested in. -

Gemeindeleben Aktuelles Aus Der Marktgemeinde Raaba-Grambach

Amtliche Mitteilung Ausgabe 2/2021 gemeindeLeben Aktuelles aus der Marktgemeinde raaba-grambach Herausnehmen: „Vierseitiges Special zum DEM LEBEN öffentlichen MEHR GEBEN! Verkehr“ wohnen_wirtschaft_wohlbefinden Wir wünschen Ihnen, liebe Gemeindebürgerinnen, Gemeindebürger und liebe Jugend, ein frohes Osterfest im Kreise Ihrer Familie. Ihr/Euer Bürgermeister Karl Mayrhold, die Gemeindevertretung und die Bediensteten der Marktgemeinde Raaba-Grambach Termine Gutschein-Aktion Regional Speisensegnungen verlängert einkaufen Seite 5 Seite 8 Seite 9 Inhalte BürgerInnenservice ...............................................................................................5 bis 9 Termine der Speisesegnung, Neue Mitarbeiterin im Bauamt, Digitales Amt, Information vom Wasserverband Grazerfeld Südost, Gemeinde Raaba-Grambach auch auf Facebook und Instagram, Grünschnittabholung, Osterjause regional einkaufen… Aktuelles aus der Gemeinde ....................................................................10 bis 23 Eröffnung fünfte Krippengruppe, Raaba-Grambach-Gutscheinaktion verlängert, Raaba-Grambach und Umlandgemeinden helfen bei Behebung von Erdbebenschäden in Kroatien, Frühjahrsputz Raaba-Grambach, Aktuelles und Rückblick der Klima- und Energiemodellregion GU Süd, Öffentlicher Verkehr in und um Raaba-Grambach, Neues aus dem FamilienZelt… Special öffentlicher Verkehr im Bund – zum Herausnehmen Wirtschaft .................................................................................................................................. 24 Unternehmen -

Bundesgesetzblatt Für Die Republik Österreich

1 von 3 BUNDESGESETZBLATT FÜR DIE REPUBLIK ÖSTERREICH Jahrgang 2006 Ausgegeben am 2. März 2006 Teil II 98. Verordnung: 2. Änderung der Wildvogel-Geflügelpestverordnung 2006 98. Verordnung der Bundesministerin für Gesundheit und Frauen zur 2. Änderung der Verordnung über Schutzmaßnahmen wegen Verdachtsfällen von Geflügelpest bei Wildvögeln (2. Änderung der Wildvogel-Geflügelpestverordnung 2006) Gemäß § 1 Abs. 5 und 6 sowie der §§ 2 und 2c des Tierseuchengesetzes RGBl. Nr. 177/1909, zuletzt geändert durch das Bundesgesetz BGBl. I Nr. 67/2005, wird verordnet: § 1. Die Anhänge der Verordnung der Bundesministerin für Gesundheit und Frauen über Schutz- maßnahmen wegen Verdachtsfällen von Geflügelpest bei Wildvögeln (Wildvogel- Geflügelpestverordnung 2006), BGBl. II Nr. 80/2006, zuletzt geändert durch die Verordnung BGBl. II Nr. 88/2006, werden durch die Anhänge zu dieser Verordnung ersetzt. § 2. Diese Verordnung tritt mit Ablauf des 2. März 2006 in Kraft. Rauch-Kallat Anhang A Schutzzonen Die Schutzzone 1 umfasst ab 18. Februar 2006: In der Steiermark: die Gemeinden Mellach, Weitendorf und Werndorf, sowie in der Gemeinde Stocking die Katastralge- meinde Sukdull, in der Gemeinde Wildon die Katastralgemeinde Wildon und in der Gemeinde Wund- schuh die Katastralgemeinde Wundschuh. Die Schutzzone 2 umfasst ab 18. Februar 2006: In der Steiermark: die Gemeinden Kaibing, St. Johann bei Herberstein, Siegersdorf bei Herberstein, Hirnsdorf und Kulm bei Weiz, sowie in der Gemeinde Stubenberg die Katastralgemeinden Vockenberg, Freienberg und Buchberg, in der Gemeinde Tiefenbach bei Kaindorf die Katastralgemeinde Untertiefenbach und in der Gemeinde Pischelsdorf in der Steiermark die Katastralgemeinde Romatschachen. Die Schutzzone 3 umfasst ab 18. Februar 2006: In Wien: den 21. und 22. Bezirk der Stadtgemeinde Wien. -

1945 – PRELOM S PRETEKLOSTJO Zgodovina Srednjeevropskih Držav Ob Koncu Druge Svetovne Vojne

1945 – A BREAK WITH THE PAST A History of Central European Countries at the End of World War Two 1945 – PRELOM S PRETEKLOSTJO Zgodovina srednjeevropskih držav ob koncu druge svetovne vojne Edited by ZDENKO ČEPIČ Book Editor Zdenko Čepič Editorial board Zdenko Čepič, Slavomir Michalek, Christian Promitzer, Zdenko Radelić, Jerca Vodušek Starič Published by Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino/ Institute for Contemporary History, Ljubljana, Republika Slovenija/Republic of Slovenia Represented by Jerca Vodušek Starič Layout and typesetting Franc Čuden, Medit d.o.o. Printed by Grafika-M s.p. Print run 400 CIP – Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 94(4-191.2)"1945"(082) NINETEEN hundred and forty-five 1945 - a break with the past : a history of central European countries at the end of World War II = 1945 - prelom s preteklostjo: zgodovina srednjeevropskih držav ob koncu druge svetovne vojne / edited by Zdenko Čepič. - Ljubljana : Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino = Institute for Contemporary History, 2008 ISBN 978-961-6386-14-2 1. Vzp. stv. nasl. 2. Čepič, Zdenko 239512832 1945 – A Break with the Past / 1945 – Prelom s preteklostjo CONTENTS Zdenko Čepič, The War is Over. What Now? A Reflection on the End of World War Two ..................................................... 5 Dušan Nećak, From Monopolar to Bipolar World. Key Issues of the Classic Cold War ................................................................. 23 Slavomír Michálek, Czechoslovak Foreign Policy after World War Two. New Winds or Mere Dreams? -

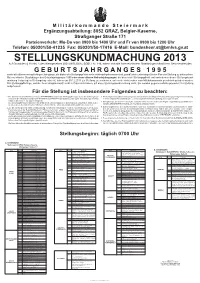

G E B U R T S J a H R G a N G E S 1 9

M i l i t ä r k o m m a n d o S t e i e r m a r k Ergänzungsabteilung: 8052 GRAZ, Belgier-Kaserne, Straßganger Straße 171 Parteienverkehr: Mo-Do von 0900 bis 1400 Uhr und Fr von 0900 bis 1200 Uhr Telefon: 050201/50-41235 Fax: 050201/50-17416 E-Mail: [email protected] STELLUNGSKUNDMACHUNG 2013 Auf Grund des § 18 Abs. 1 des Wehrgesetzes 2001 (WG 2001), BGBl. I Nr. 146, haben sich alle österreichischen Staatsbürger männlichen Geschlechtes des G E B U R T S J A H R G A N G E S 1 9 9 5 sowie alle älteren wehrpflichtigen Jahrgänge, die bisher der Stellungspflicht noch nicht nachgekommen sind, gemäß dem unten angeführten Plan der Stellung zu unterziehen. Österreichische Staatsbürger des Geburtsjahrganges 1995 oder eines älteren Geburtsjahrganges, bei denen die Stellungspflicht erst nach dem in dieser Stellungskund- machung festgelegten Stellungstag entsteht, haben am 09.12.2013 zur Stellung zu erscheinen, sofern sie nicht vorher vom Militärkommando persönlich geladen wurden. Für Stellungspflichtige, welche ihren Hauptwohnsitz nicht in Österreich haben, gilt diese Stellungskundmachung nicht. Sie werden gegebenenfalls gesondert zur Stellung aufgefordert. Für die Stellung ist insbesondere Folgendes zu beachten: 1. Für den Bereich des Militärkommandos STEIERMARK werden die Stellungspflichtigen durch die Stellungskom- 3. Bei Vorliegen besonders schwerwiegender Gründe besteht die Möglichkeit, dass Stellungspflichtige auf ihren Antrag missionen der Militärkommanden STEIERMARK und KÄRNTEN der Stellung unterzogen. Das Stellungsverfahren in einem anderen Bundesland oder zu einem anderen Termin der Stellung unterzogen werden. nimmt in der Regel 1 1/2 Tage in Anspruch. -

NATIONALISM TODAY: CARINTHIA's SLOVENES Part I: the Legacy Ofhistory by Dennison I

SOUTHEAST EUROPE SERIES Vol. XXII No. 4 (Austria) NATIONALISM TODAY: CARINTHIA'S SLOVENES Part I: The Legacy ofHistory by Dennison I. Rusinow October 1977 The bombsmostly destroying Osvobodilna other world is Slovene, and in the valleys of Carin- Fronta or AbwehrMimpfer monumentshave been thia, the two peoples and cultures have been mixed too small and too few and have done too little for more than eleven hundred years. Until the damage to earn much international attention in this "national awakening" of the nineteenth century, age of ubiquitous terrorism in the name of some nobody seems to have minded. Then came the Slo- ideological principle or violated rights. Moreover, vene renaissance and claims to cultural and social the size of the national minority in question, the equality for Slovenes qua Slovenes, backed by the quality of their plight, and the potentially wider shadows of Austro-Slavism, South-(Yugo-)Slavism, Austrian and international repercussions ofthe con- and pan-Slavism. The German Carinthians, feeling flict all pale into insignificance alongside the prob- threatened in their thousand-year cultural, political, lems of the Cypriots, of the Northern Irish, of the and economic dominance on the borderland, Basques, of the Palestinian and Overseas Chinese reacted with a passion that became obsessive and diasporas, of the non-Russian peoples of the Soviet that was to culminate in Nazi attempts during Union, or of many others. Despite these disclaimers, World War II to eradicate the Slovene Carinthians however, the problem of the Carinthian Slovenes is through a combination of forcible assimilation and worth examining for more than its local and population transfers. -

Slovenia As an Outpost of Th~ Third Reich

SLOVENIA AS AN OUTPOST OF TH~ THIRD REICH By HELGA HORIAK HARRIMAN 1\ Bachelor of Arts Wells College Aurora, New York 1952 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1969 STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SEP 29 1969 SLOVENIA AS AN OUTPOST OF THE THIRD REICH Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College ii PREFACE This study is concerned primarily with the Nazi occupation of Northern Yugoslavia during 1941 and 1942. Hitler's plan for converting Slovenia into a germanized frontier zone of the Third Reich is assessed in the light of Slovene history, most particularly since 1918. The evidence for the Nazi resettlement program designed to achieve Hitler's goal came from manuscript documents, which were written largely by the SS officers in charge of population manipulation. I wish to express appreciation to members of my advisory committee t from the Department of History at Oklahoma State University who gave helpful criticism in the preparation of the text. Professor Douglas Hale served as committee chairman and offered valuable advice concern- ing the study from its inception to its conclusion. Professor George Jewsbury imparted to its development his own keen understanding of Eastern Europe. To Professors John Sylvester and Charles Dollar, who read the study in its final form, I am also indebted. In addition, I wish to thank my father, Dr. E. A. V. Horiak, for his insightful comments. Dr. Joseph Suhadolc of the Department of For- eign Languages at Northern Illinois University gave freely of his time in reviewing the text.