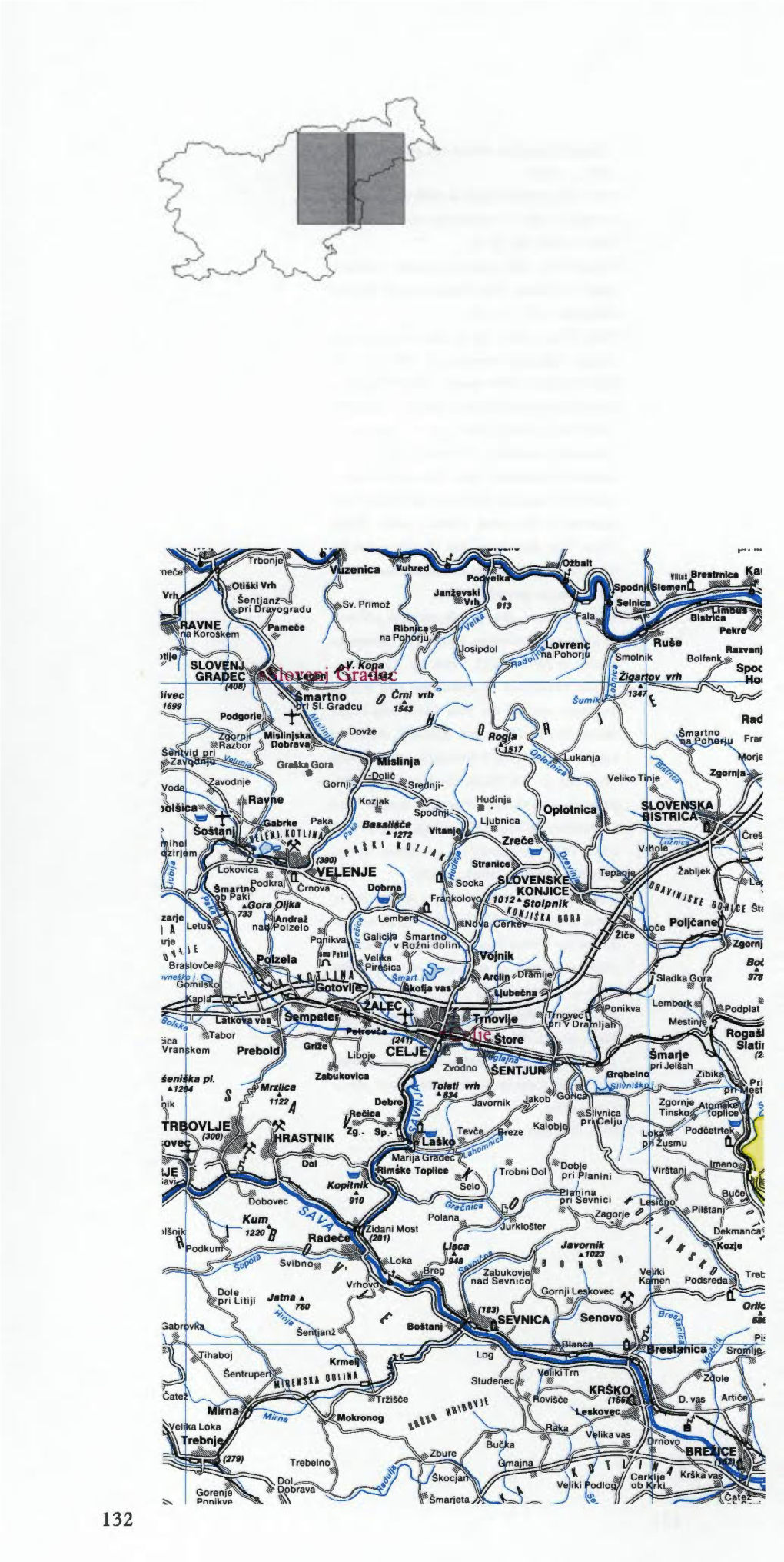

The Establishment and Development of Mediaeval Towns in Slovene Styria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Communist Memory Culture and the Historiography of the Second World War and the Post-War Execution of Slovenian Collaborationists

Croatian Political Science Review, Vol. 55, No. 2, 2018, pp. 33-49 33 Original research article Received: 21 August 2017 DOI: 10.20901/pm.55.2.02 Post-Communist Memory Culture and the Historiography of the Second World War and the Post-War Execution of Slovenian Collaborationists OTO LUTHAR Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts Summary This paper aims to summarize the transformations in contemporary Slove- nia’s post-socialist memorial landscape as well as to provide an analysis of the historiographical representation of The Second World War in the Slovenian territory. The analysis focuses on the works of both Slovenian professional and amateur historiographical production, that address historic developments which took place during the Second World War and in its immediate aftermath from the perspective of the post-war withdrawal of the members of various military units (and their families) that collaborated with the occupiers during the Second World War. Keywords: Slovenes, Partisans, Home Guards, Historiography, Memory Introduction The debate on post-communist/post-socialist historical interpretation has become an inseparable part of the new politics of the past across Eastern and Southeastern Europe. In Slovenia, the once-vivid historiographical debate on the nature of histo- rical explanation has been ever since largely overshadowed by new attempts to mo- nopolize historical interpretation. The discussion, that has been led from the 1980s onwards, has brought forward new forms of historical representation which have once again given way to the politicized reinterpretation of the most disputed parts of the Second World War and the subsequent time of socialism. Like in some other parts of post-socialist Europe, the past has become a “morality drama” and a “pas- 34 Luthar, O., Post-Communist Memory Culture and the Historiography of the Second World War.. -

Portrait of the Regions – Slovenia Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities 2000 – VIII, 80 Pp

PORTRAIT OF THE REGIONS 13 17 KS-29-00-779-EN-C PORTRAIT OF THE REGIONS VOLUME 9 SLOVENIA VOLUME 9 SLOVENIA Price (excluding VAT) in Luxembourg: ECU 25,00 ISBN 92-828-9403-7 OFFICE FOR OFFICIAL PUBLICATIONS OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES EUROPEAN COMMISSION L-2985 Luxembourg ࢞ eurostat Statistical Office of the European Communities PORTRAIT OF THE REGIONS VOLUME 9 SLOVENIA EUROPEAN COMMISSION ࢞ I eurostat Statistical Office of the European Communities A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu.int). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2000 ISBN 92-828-9404-5 © European Communities, 2000 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Belgium II PORTRAIT OF THE REGIONS eurostat Foreword The accession discussions already underway with all ten of the Phare countries of Central and Eastern Europe have further boosted the demand for statistical data concerning them. At the same time, a growing appreciation of regional issues has raised interest in regional differences in each of these countries. This volume of the “Portrait of the Regions” series responds to this need and follows on in a tradition which has seen four volumes devoted to the current Member States, a fifth to Hungary, a sixth volume dedicated to the Czech Republic and Poland, a seventh to the Slovak Republic and the most recent volume covering the Baltic States, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Examining the 12 statistical regions of Slovenia, this ninth volume in the series has an almost identical structure to Volume 8, itself very similar to earlier publications. -

“(Slovene) Medieval History” in the Book's Subtitle Should Be

INTRODUCTION Th e phrase “(Slovene) medieval history” in the book’s subtitle should be understood in its geographical, not ethnic sense: it does not mean that the papers deal with the history of the Slovenes, but rather with historical developments and phenomena from the Middle Ages in the area that is today associated with (the Republic of) Slovenia. At the same time, we must be aware that even such a geographical defi nition can only be approximate and provisional: the contemporary frame- work of the state certainly should not limit our view or research when dealing with remote periods, when many political, linguistic, ethnical, and other borders diff ered essentially and the area had a diff erent struc- ture. Th e developments in the coastal towns of present-day Slovenia, for instance, cannot be adequately understood and described without knowledge and consideration of the conditions in the whole of Istria, the historical province that is today divided between Italy, Slovenia, and Croatia, or without giving due consideration to the roles played by the Byzantine, Frankish, or Venetian authorities in the peninsula. To quote another example, the situation is similar to that of Styria (or Carinthia, or Gorizia, etc.). Since 1918, that historical Land, formed in the 12th century, has been divided between two states, Austria and Slovenia (Yugoslavia) into Austrian and Slovene Styria, and the latter occupies about one third of the former Land. It is clear, then, that we can research and describe some chapters from its history only if we focus on Styria as a whole, regardless of its current borders; or, in other words, if we view it – and this is true of everything in history – as a variable historical category that cannot be treated outside the context of the period we are interested in. -

1945 – PRELOM S PRETEKLOSTJO Zgodovina Srednjeevropskih Držav Ob Koncu Druge Svetovne Vojne

1945 – A BREAK WITH THE PAST A History of Central European Countries at the End of World War Two 1945 – PRELOM S PRETEKLOSTJO Zgodovina srednjeevropskih držav ob koncu druge svetovne vojne Edited by ZDENKO ČEPIČ Book Editor Zdenko Čepič Editorial board Zdenko Čepič, Slavomir Michalek, Christian Promitzer, Zdenko Radelić, Jerca Vodušek Starič Published by Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino/ Institute for Contemporary History, Ljubljana, Republika Slovenija/Republic of Slovenia Represented by Jerca Vodušek Starič Layout and typesetting Franc Čuden, Medit d.o.o. Printed by Grafika-M s.p. Print run 400 CIP – Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 94(4-191.2)"1945"(082) NINETEEN hundred and forty-five 1945 - a break with the past : a history of central European countries at the end of World War II = 1945 - prelom s preteklostjo: zgodovina srednjeevropskih držav ob koncu druge svetovne vojne / edited by Zdenko Čepič. - Ljubljana : Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino = Institute for Contemporary History, 2008 ISBN 978-961-6386-14-2 1. Vzp. stv. nasl. 2. Čepič, Zdenko 239512832 1945 – A Break with the Past / 1945 – Prelom s preteklostjo CONTENTS Zdenko Čepič, The War is Over. What Now? A Reflection on the End of World War Two ..................................................... 5 Dušan Nećak, From Monopolar to Bipolar World. Key Issues of the Classic Cold War ................................................................. 23 Slavomír Michálek, Czechoslovak Foreign Policy after World War Two. New Winds or Mere Dreams? -

NATIONALISM TODAY: CARINTHIA's SLOVENES Part I: the Legacy Ofhistory by Dennison I

SOUTHEAST EUROPE SERIES Vol. XXII No. 4 (Austria) NATIONALISM TODAY: CARINTHIA'S SLOVENES Part I: The Legacy ofHistory by Dennison I. Rusinow October 1977 The bombsmostly destroying Osvobodilna other world is Slovene, and in the valleys of Carin- Fronta or AbwehrMimpfer monumentshave been thia, the two peoples and cultures have been mixed too small and too few and have done too little for more than eleven hundred years. Until the damage to earn much international attention in this "national awakening" of the nineteenth century, age of ubiquitous terrorism in the name of some nobody seems to have minded. Then came the Slo- ideological principle or violated rights. Moreover, vene renaissance and claims to cultural and social the size of the national minority in question, the equality for Slovenes qua Slovenes, backed by the quality of their plight, and the potentially wider shadows of Austro-Slavism, South-(Yugo-)Slavism, Austrian and international repercussions ofthe con- and pan-Slavism. The German Carinthians, feeling flict all pale into insignificance alongside the prob- threatened in their thousand-year cultural, political, lems of the Cypriots, of the Northern Irish, of the and economic dominance on the borderland, Basques, of the Palestinian and Overseas Chinese reacted with a passion that became obsessive and diasporas, of the non-Russian peoples of the Soviet that was to culminate in Nazi attempts during Union, or of many others. Despite these disclaimers, World War II to eradicate the Slovene Carinthians however, the problem of the Carinthian Slovenes is through a combination of forcible assimilation and worth examining for more than its local and population transfers. -

Slovenia As an Outpost of Th~ Third Reich

SLOVENIA AS AN OUTPOST OF TH~ THIRD REICH By HELGA HORIAK HARRIMAN 1\ Bachelor of Arts Wells College Aurora, New York 1952 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1969 STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SEP 29 1969 SLOVENIA AS AN OUTPOST OF THE THIRD REICH Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College ii PREFACE This study is concerned primarily with the Nazi occupation of Northern Yugoslavia during 1941 and 1942. Hitler's plan for converting Slovenia into a germanized frontier zone of the Third Reich is assessed in the light of Slovene history, most particularly since 1918. The evidence for the Nazi resettlement program designed to achieve Hitler's goal came from manuscript documents, which were written largely by the SS officers in charge of population manipulation. I wish to express appreciation to members of my advisory committee t from the Department of History at Oklahoma State University who gave helpful criticism in the preparation of the text. Professor Douglas Hale served as committee chairman and offered valuable advice concern- ing the study from its inception to its conclusion. Professor George Jewsbury imparted to its development his own keen understanding of Eastern Europe. To Professors John Sylvester and Charles Dollar, who read the study in its final form, I am also indebted. In addition, I wish to thank my father, Dr. E. A. V. Horiak, for his insightful comments. Dr. Joseph Suhadolc of the Department of For- eign Languages at Northern Illinois University gave freely of his time in reviewing the text. -

Pumpkin Seed Oil from Styria and Prekmurje.Pptx

Pumpkin seed oil from Styria and Prekmurje What is it? • Pumpkin seed oil is produced from pumpkin seeds. • It‘s colour is dark green-brown. • It has highly aromac „nuBy“ taste. Tradi@onal producon 1. The seeds are cleaned from pumpkin leFovers and peeled. 2. Pumpkin seeds are fully dried for several weeks and cleaned once again. 3. Seeds are grinded in special machine. 4. Water is added and seeds are roasted for half hour in 100 – 110 degrees. 5. Oil is compressed from the pumpkin seed mass. 6. AFer one week oil is naturally cleaned and ready to pack. How much pumpkin seeds? • You need 3 kg of pumpkin seeds for 1 liter of pumpkin oil (if seeds are roasted). • You need 6 kg of pumpkin seeds for 1 liter of pumpkin oil (if seeds are cold-pressed). • For 3 kg of pumpkin seeds you need 30-40 pumpkins! Where is it produced? • It‘s tradi@onal (protected) product of North- Eastern Slovenia and South-Eastern Austria. • Pumpkin seed oil is also produced in parts of Croaa, Romania (Transylvania) and Romania. • The earliest produc@on is dated to 1697. Storage • Pumpkin seed oil is light-sensi@ve. • It needs to be stored in cold and dry place. • If it is exposed to light it looses vitamins and minerals and it becomes bier. Use in culinary • Salad dressings • Addi@on to bread/cakes • Addi@on to soups and sauces • Deserts (famous combinaon with vanilla ice cream) • Cookies & Chocolate • Some people don‘t recommend it for cooking! • More on: hBp://www.pumpkinseedoil.cc/PPF/start/rezepte.asp/l/e/index1.asp Medical benefits • Prostate cure (Benign prostac hyperplasia). -

Trips Around Graz Nature

TRIPS AROUND GRAZ NATURE. CULTURE. ENJOYMENT. SPORT. HEALTH. Right on Graz’s doorstep there are an endless number of things to Graz for sports activities or for relaxation and wellness? Things to see, enjoy and do. discover – and even more to enjoy ... Everything is possible! WELL WORTH THE TRIP! ACTIONS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS! Leaving behind the urban flair of the city, it’s just a couple of miles For those who enjoy walking, the Styrian countryside offers a huge to the real countryside – how wonderful to breathe fresh air in the range of well-marked paths. Graz is “the most bicycle-friendly city midst of nature, to take in the beautiful, unspoilt Styrian landscape. in Austria”, and the surrounding area can also be explored by bike Discover striking natural wonders and cultural treasures, steeply slop- – whether on the bicycle path along the River Mur, a tour around ing vineyards, the summer residence of the world-famous Lipizzaner Graz or on the mountain bike routes. For golfers there is an Eldo- horses and massive stone fortresses of past centuries on the Styrian rado of wonderful golf courses! And if you’re after relaxation and castle route. Wherever you go, you’ll find the traditional delicacies wellness: close to the city lies a great variety of spas. of local cuisine – taste internationally renowned Styrian wines at the producer’s vineyard and buy fresh pumpkin-seed oil directly from the farmer to take back home with you! GRAZ TOURISMUS INFORMATION A-8010 Graz, Herrengasse 16, T +43/316/8075-0, F ext. -

Fertility Decline in the Southeastern Austrian Crown Land. Was There a Hajnal Line Or a Transitional Zone?

Fertility Decline in the southeastern Austrian Crown land. Was there a Hajnal line or a transitional zone? Peter Teibenbacher Working Paper 2012-02 September 28, 2012 GRAZ OF OF Working Paper Series Faculty of Social and Economic Sciences Karl-Franzens-University Graz ISSN 2304-7658 sowi.uni-graz.at/de/forschen/working-paper-series/ [email protected] UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY Fertility Decline in the southeastern Austrian Crown land. Was there a Hajnal line or a transitional zone? Peter Teibenbacher a,* Working Paper 2012-02 September 28, 2012 Abstract There is a substantial body of literature on the subject of fertility decline in Europe during the first demographic transition. Historical demographic research on this topic started in Western Europe, but, as a result of the discussion of the Hajnal line thesis, the decline in fertility has been more thoroughly explored for Eastern Europe (especially Poland and Hungary) than for areas in between, like Austria. This project and this working paper will seek to close this gap by addressing the question of whether the Austrian Crown lands in the southeast represented not just an administrative, but also a demographic border. Using aggregated data from the political districts, this paper will review the classic research about, as well as the methods and definitions of, fertility decline. Our results show that, even the Crown land level, which was used in the Princeton Fertility Project, is much too high for studying significant regional and systemic differences and patterns of fertility changes and decline. This process is interpreted as a result of economic and social modernization, which brought new challenges, as well as new options. -

Developing Sustainable and Flexible Rural–Urban Connectivity Through Complementary Mobility Services

sustainability Article Developing Sustainable and Flexible Rural–Urban Connectivity through Complementary Mobility Services Lisa Bauchinger 1 , Anna Reichenberger 2 , Bryonny Goodwin-Hawkins 3 , Jurij Kobal 4, Mojca Hrabar 4 and Theresia Oedl-Wieser 1,* 1 Federal Institute of Agricultural Economics, Rural and Mountain Research, 1030 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] 2 Regional Management of the Metropolitan Area of Styria, 8010 Graz, Austria; [email protected] 3 Countryside and Community Research Institute, University of Gloucestershire, Cheltenham GL50 4AZ, UK; [email protected] 4 Oikos, Sustainable development Inc., 1241 Kamnik, Slovenia; [email protected] (J.K.); [email protected] (M.H.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +43-1-71100-637518 Abstract: Transport can play a key role in mitigating climate change, through reducing traffic, emis- sions and dependency on private vehicles. Transport is also crucial to connect remote areas to central or urban areas. Yet, sustainable and flexible transport is among the greatest challenges for rural areas and rural–urban regions. Innovative transport concepts and approaches are urgently needed to foster sustainable and integrated regional development. This article addresses challenges of sustain- ability, accessibility, and connectivity through examining complementary systems to existing public transport, including demand-responsive transport and multimodal mobility. We draw upon case Citation: Bauchinger, L.; studies from the Metropolitan Area of Styria, Ljubljana Urban Region and rural Wales (GUSTmobil, Reichenberger, A.; REGIOtim, EURBAN, Bicikelj, Bwcabus, Grass Routes). In-depth analysis through a mixed-methods Goodwin-Hawkins, B.; Kobal, J.; case study design captures the complexity behind these chosen examples, which form a basis for Hrabar, M.; Oedl-Wieser, T. -

Making History in High Medieval Styria (1185-1202)—The Vorau Manuscript in Its Secular and Spiritual Context

Making History in High Medieval Styria (1185-1202)—The Vorau Manuscript in its Secular and Spiritual Context by Jacob Wakelin A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Jacob Wakelin 2018 Making History in High Medieval Styria (1185-1202)—The Vorau Manuscript in its Secular and Spiritual Context Jacob Wakelin Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto 2018 Abstract This dissertation focuses on the historical, social, and political context of the Vorau manuscript (Stiftsarchiv Vorau Codex 276), a collection of more than a dozen Middle High German poems from the late eleventh to the mid-twelfth century in addition to Otto of Freising’s Gesta Friderici I. imperatoris. When taken together, the manuscript’s disparate assortment of texts creates a roughly coherent history of the world from Genesis down to about 1160. Compiled by the Augustinian canons of the Styrian house towards the end of the twelfth century under the provost Bernard I, the manuscript references local historical events and individuals that were intimately tied to the region’s monastic houses. The Otakars (1055-1192) and Babenbergs (1192-1246) were the founders and advocates of a large number of the monastic communities, and this dissertation argues that the interplay of interests between the Styrian court and its religious houses forms the backdrop to the Vorau manuscript’s creation. These interests centred on the political legitimacy, social relevance, and stability of both parties that resulted from a monastery’s role in creating a history of a dynasty through commemorative practices and historical writing. -

Uncanny Styria

j:makieta 13-5-2019 p:149 c:1 black–text PHILOLOGICAL STUDIES. LITERARY RESEARCH [PFLIT] Warszawa 2019 PFLIT, issue 9(12), part 1: 149−162 PATRYCJUSZ PAJĄK Institute of Western and Southern Slavic Studies University of Warsaw UNCANNY STYRIA Keywords: Styria, English literature, borderlands, the uncanny, the nobility Słowa kluczowe: Styria, literatura angielska, graniczność, niesamowitość, szlachta Summary The nineteenth century in the West was a period of intellectual and artistic fascination with the East, both distant and near: Asian and Eastern European. One of the regions that attracted the interest of Western Europeans was Styria, situated on the border separating Austria from Hungary and the Balkans, that is, the West from the East. Borderland cultural phenomena stimulate the imagination as much as exotic phenomena. Both disturb with their hybrid character, which results from the mixing of elements from familiar and alien cultures. With their duality and ambiguity, borderlands are the source of the uncanny, which in the Western literature of the nineteenth century became the basic ingredient of the Western image of the Styrian lands. Uncanny Styria was discovered by Basil Hall, a Scottish traveler who reported the impres- sions of his stay in this region in his 1830s travelogue Schloss Hainfeld; or, a Winter in Lower Styria. In the second half of the century, two Irishmen wrote about the uncanny Styrian borderland: Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu and Bram Stoker. Both associated Styria with vampirism: the former in the 1870s novella Carmilla, the latter in the 1890s short story Dracula’s Guest. The central thread that runs through all three texts is the decline of Styrian nobility.