Lachlan Campbell's Letters to Edward Lhwyd, 1704–7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bartlett, T. (2020) Time, the Deer, Is in the Wood: Chronotopic Identities, Trajectories of Texts and Community Self-Management

Bartlett, T. (2020) Time, the deer, is in the wood: chronotopic identities, trajectories of texts and community self-management. Applied Linguistics Review, (doi: 10.1515/applirev-2019-0134). This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/201608/ Deposited on: 24 October 2019 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Tom Bartlett Time, the deer, is in the wood: Chronotopic identities, trajectories of texts and community self-management Abstract: This paper opens with a problematisation of the notion of real-time in discourse analysis – dissected, as it is, as if time unfolded in a linear and regular procession at the speed of speech. To illustrate this point, the author combines Hasan’s concept of “relevant context” with Bakhtin’s notion of the chronotope to provide an analysis of Sorley MacLean’s poem Hallaig, with its deep-rootedness in space and its dissolution of time. The remainder of the paper is dedicated to following the poem’s metamorphoses and trajectory as it intertwines with Bartlett’s own life and family history, creating a layered simultaneity of meanings orienting to multiple semio-historic centres. In this way the author (pers. comm.) “sets out to illustrate in theory, text analysis and (self-)history the trajectories taken by texts as they cross through time and space; their interconnectedness -

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-Names and Society: Analysis of the Medieval Districts of Forsa and Moloros in the Parish of Torosay, Mull

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-names and society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8224/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Settlement-Names and Society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. Alasdair C. Whyte MA MRes Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Celtic and Gaelic | Ceiltis is Gàidhlig School of Humanities | Sgoil nan Daonnachdan College of Arts | Colaiste nan Ealain University of Glasgow | Oilthigh Ghlaschu May 2017 © Alasdair C. Whyte 2017 2 ABSTRACT This is a study of settlement and society in the parish of Torosay on the Inner Hebridean island of Mull, through the earliest known settlement-names of two of its medieval districts: Forsa and Moloros.1 The earliest settlement-names, 35 in total, were coined in two languages: Gaelic and Old Norse (hereafter abbreviated to ON) (see Abbreviations, below). -

Langues, Accents, Prénoms & Noms De Famille

Les Secrets de la Septième Mer LLaanngguueess,, aacccceennttss,, pprréénnoommss && nnoommss ddee ffaammiillllee Il y a dans les Secrets de la Septième Mer une grande quantité de langues et encore plus d’accents. Paru dans divers supplément et sur le site d’AEG (pour les accents avaloniens), je vous les regroupe ici en une aide de jeu complète. D’ailleurs, à mon avis, il convient de les traiter à part des avantages, car ces langues peuvent être apprises après la création du personnage en dépensant des XP contrairement aux autres avantages. TTaabbllee ddeess mmaattiièèrreess Les différentes langues 3 Yilan-baraji 5 Les langues antiques 3 Les langues du Cathay 5 Théan 3 Han hua 5 Acragan 3 Khimal 5 Alto-Oguz 3 Koryo 6 Cymrique 3 Lanna 6 Haut Eisenör 3 Tashil 6 Teodoran 3 Tiakhar 6 Vieux Fidheli 3 Xian Bei 6 Les langues de Théah 4 Les langues de l’Archipel de Minuit 6 Avalonien 4 Erego 6 Castillian 4 Kanu 6 Eisenör 4 My’ar’pa 6 Montaginois 4 Taran 6 Ussuran 4 Urub 6 Vendelar 4 Les langues des autres continents 6 Vodacci 4 Les langages et codes secrets des différentes Les langues orphelines ussuranes 4 organisations de Théah 7 Fidheli 4 Alphabet des Croix Noires 7 Kosar 4 Assertions 7 Les langues de l’Empire du Croissant 5 Lieux 7 Aldiz-baraji 5 Heures 7 Atlar-baraji 5 Ponctuation et modificateurs 7 Jadur-baraji 5 Le code des pierres 7 Kurta-baraji 5 Le langage des paupières 7 Ruzgar-baraji 5 Le langage des “i“ 8 Tikaret-baraji 5 Le code de la Rose 8 Tikat-baraji 5 Le code 8 Tirala-baraji 5 Les Poignées de mains 8 1 Langues, accents, noms -

The Celtic Who's Wh

/ -^ H./n, bz ^^.c ' ^^ Jao ft « V o -i " EX-LlBRlS HEW- MORRISON M D E The Celtic Who's Wh. THE CELTIC WHO'S WHO Names and Addresses of Workers Who contribute to Celtic Literature, Music or other Cultural Activities Along with other Information KIRKCALDY, SCOTLAND: THE FIFESHIRE ADVERTISER LIMITED 1921 LAURISTON CASTLE LIBRARY ACCESSION CONTENTS Preface. ; PREFACE This compilation was first suggested by the needs nf the organisers of tlie Pau-Celtic Congjess held in Edin- burgh in May, 1920. Acting as convener ol the Scottish Committee for that event, the editor found that there was in existence no list of persons who took an acti^•p interest in such matters, either in Scotland or in any of the other Celtic countries. His resolve to meet this want was cordially approved by the lenxlers of tlie Congress circulars were issued to all wlrose addresses could be discovered, and these were invited to suggest the n-iines of others who ought to be included. The net result is not quite up to expectation, but it is better tlaan at first seemed probable. The Celt may not really be more shy or n.ore dilatory than men of other blood, but certainly the response to this elTort has not indicated on his pfirt any undue forwardness. Even now, after the lapse of a year and the issue of a second ;ind a third circular, tlie list of Celtic aaithors niid inu<;iciii::i.s is far from full. Perhaps a second edition of the l)"(>k, when called for, may be more complete. -

Identity in Gaelic Drama 1900-1949 Susan Ross University of Glasgow

Identity in Gaelic Drama 1900-1949 Susan Ross University of Glasgow Michelle Macleod and Moray Watson have described drama and prose fiction as being ‘in the shadow of the bard’ in terms of their place in the canon of Gaelic literature. (2007) Analysis and review of the extant drama materials show, however, that the Gaelic playwright Tormod Calum Dòmhnallach (Norman Malcolm MacDonald), 1 was right in saying in 1986 that ‘Gaelic theatre […] has been in existence for longer than many of us suspect’. (MacDonald 1986: 147) It is believed that the first Gaelic play (fully in Gaelic, rather than bilingual English with Gaelic) was performed by the Edinburgh University Celtic Society in 1902 although it is no longer known which play or sketch was performed. (Macleod and Watson 2007: 280) In the first decade of the twentieth century, Còisir Chiùil Lunnainn (London Musical Choir) also performed plays at their annual concert in London.2 This article looks at the first half of the twentieth century, when stage drama in Gaelic was being created, to investigate how Gaelic playwrights represented Scottish Gaels and their culture in this new art form. In terms of their artistic merit, Gaelic plays between 1900 and the Second World War are not generally held in high esteem, having previously been described as ‘outstanding neither as to quantity or quality’. (MacLeod 1969: 146) Despite this, there is value in what they reveal about identity and attitudes of the writers, many of whom were prominent figures in the Gaelic movement. An overview of some of the principal themes and tropes of the drama of this period will be presented, considering in particular how the writers negotiate what it meant to be a Gael in the early twentieth century. -

THE PLACE-NAMES of ARGYLL Other Works by H

/ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES THE PLACE-NAMES OF ARGYLL Other Works by H. Cameron Gillies^ M.D. Published by David Nutt, 57-59 Long Acre, London The Elements of Gaelic Grammar Second Edition considerably Enlarged Cloth, 3s. 6d. SOME PRESS NOTICES " We heartily commend this book."—Glasgow Herald. " Far and the best Gaelic Grammar."— News. " away Highland Of far more value than its price."—Oban Times. "Well hased in a study of the historical development of the language."—Scotsman. "Dr. Gillies' work is e.\cellent." — Frce»ia7is " Joiifnal. A work of outstanding value." — Highland Times. " Cannot fail to be of great utility." —Northern Chronicle. "Tha an Dotair coir air cur nan Gaidheal fo chomain nihoir."—Mactalla, Cape Breton. The Interpretation of Disease Part L The Meaning of Pain. Price is. nett. „ IL The Lessons of Acute Disease. Price is. neU. „ IIL Rest. Price is. nef/. " His treatise abounds in common sense."—British Medical Journal. "There is evidence that the author is a man who has not only read good books but has the power of thinking for himself, and of expressing the result of thought and reading in clear, strong prose. His subject is an interesting one, and full of difficulties both to the man of science and the moralist."—National Observer. "The busy practitioner will find a good deal of thought for his quiet moments in this work."— y^e Hospital Gazette. "Treated in an extremely able manner."-— The Bookman. "The attempt of a clear and original mind to explain and profit by the lessons of disease."— The Hospital. -

Gaelic Names of Pibrochs a Concise Dictionary Edited by Roderick D

February 2013 Gaelic names of Pibrochs A Concise Dictionary edited by Roderick D. Cannon Introduction Sources Text Bibliography February 2013 Introduction This is an alphabetical listing of the Gaelic names of pibrochs, taken from original sources. The great majority of sources are manuscript and printed collections of the tunes, in music notation appropriate for the bagpipe, that is, in staff notation or in canntaireachd. In addition, there are a few arranged for piano or fiddle, but only when the tunes correspond to known bagpipe versions. The main purpose of the work is to make available authentic versions of all authentic names, to explain apparent inconsistences and difficulties in translation, and to account for the forms of the names as we find them. The emphasis here is on the names, not the tunes as such. Many tunes have a variety of different names, but here the variants are only listed in the same entry when they are evidently related. Names which are semantically unrelated are placed in separate entries, even when linked by tradition such as Craig Ealachaidh and Cruinnneachdh nan Grandach. But in such cases they are linked by cross-references, and the traditions which explain the connection are mentioned in the discussions. Different names which merely sound similar are also cross-referenced, whether or not they apply to the same tune. Different names for the same tune, with no apparent connection, are not cross-referenced. Different tunes with the same name are given separate entries, though of course these appear consecutively in the list. In each entry the first name, in bold type, is presented in modern Gaelic spelling except that the acute accent is retained, e.g. -

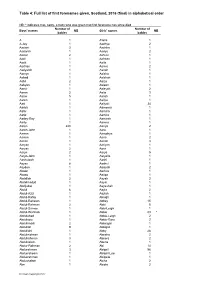

Table 4: Full List of First Forenames Given, Scotland, 2016 (Final) in Alphabetical Order

Table 4: Full list of first forenames given, Scotland, 2016 (final) in alphabetical order NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has since died Number of Number of Boys' names NB Girls' names NB babies babies A 1 A'lelia 1 A-Jay 1 Aadhya 2 Aadam 3 Aadrika 1 Aadarsh 1 Aadya 2 Aaden 2 Aafeen 1 Aadi 1 Aafreen 1 Aadit 1 Aaila 1 Aadrian 1 Aaima 2 Aadyanth 1 Aairah 1 Aaeryn 1 Aaisha 1 Aahad 1 Aaishah 1 Aahil 2 Aaiza 1 Aahyan 1 Aaleen 1 Aamir 1 Aaleyah 2 Aaran 2 Aalia 3 Aarav 5 Aaliah 1 Aaren 1 Aaliya 1 Aari 1 Aaliyah 34 Aarick 1 Aameera 1 Aariv 1 Aamina 1 Aariz 1 Aamira 1 Aarley-Ray 1 Aamirah 1 Aarlo 1 Aamna 1 Aaron 240 Aanya 2 Aaron-John 1 Aara 1 Aarran 1 Aaradhya 1 Aarron 1 Aaria 2 Aarvin 1 Aariah 3 Aaryan 1 Aariyah 1 Aaryav 2 Aarvi 1 Aaryn 2 Aarya 5 Aaryn-John 1 Aaryella 1 Aashutosh 1 Aashi 1 Aayan 8 Aashvi 1 Aayden 1 Aasiyah 2 Abaan 1 Aathira 1 Abaas 1 Aatiqa 1 Abdallah 2 Aayah 2 Abdelmadjid 1 Aayat 1 Abdijabar 1 Aayeshah 1 Abdul 6 Aayla 2 Abdul-Aziz 1 Aaylah 1 Abdul-Rafay 1 Abaigh 1 Abdul-Raheem 1 Abbey 15 Abdul-Rahman 2 Abbi 5 Abdul-Samee 1 Abbi-Leigh 1 Abdul-Wahhab 1 Abbie 83 * Abdulahad 1 Abbie-Leigh 2 Abdulaziz 1 Abbie-Rose 2 Abdulhaadi 2 Abbiegail 1 Abdullah 9 Abbigail 1 Abdullahi 1 Abby 28 Abdulmohsen 1 Abeeha 2 Abdulrahman 3 Abeera 2 Abdulsalam 1 Abena 1 Abdur-Rahman 2 Abi 14 Abdurahman 3 Abigail 96 Abdurraheem 1 Abigail-Lee 1 Abdurrahman 1 Abigaile 1 Abdussalam 1 Abiha 2 Abe 1 Abiola 2 © Crown Copyright 2017 Table 4 (continued) NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has -

Gaelic Names of Pibrochs: a Classification1

Gaelic Names of Pibrochs: A Classification1 Roderick D. Cannon Hon. Fellow, School of Scottish Studies, University of Edinburgh CONTENTS 1 Introduction 3 2 Sources 2.1. Pipe Music Collections 4 2.2 Other Sources 5 3 A Classification of Piobaireachd Names 8 4 Conflict and Confusion? 10 5 Type I: Functional Names 5.1 Cumha 14 5.2 Fàilte 18 5.3 Cruinneachadh 19 5.4 "Rowing tunes" 21 5.5 Words meaning “March” 22 5.6 Words meaning “Battle” 24 6 English and Gaelic 25 7 Type II: Technical Names 7.1 Pìobaireachd 26 7.2 Port 26 7.3 Gleus 27 7.4 Cor/ Cuir 28 7.5 Caismeachd 30 7.6 Aon-tlachd 32 8 Conclusions 32 Acknowledgements NOTES SOURCES BIBLIOGRAPHY 1. Introduction The classical music of the Highland bagpipe, usually called piobaireachd, but perhaps more correctly ceol mòr, consists of a large number of extended compositions in the form of air with variations. They were written down from oral tradition, mainly in the first half of the nineteenth century. Although pibrochs have continued to be composed since that time, especially in the last few decades, it is the pre-1850 pieces which are generally accepted as the classical canon.2 It is safe to assume that all the pibroch players who noted the music in writing spoke Gaelic as their first language.3 Certainly the great majority of pieces have been recorded with Gaelic titles as well as English. There can be little doubt that the English titles are generally translations of the Gaelic rather than the other way round. -

Babies' First Forenames: Births Registered in Scotland in 1995

Babies' first forenames: births registered in Scotland in 1995 Information about the basis of the list can be found via the 'Babies' First Names' page on the National Records of Scotland website. Boys Girls Position Name Number of babies Position Name Number of babies 1 Ryan 1026 1 Lauren 874 2 Andrew 859 2 Rebecca 730 3 Daniel 699 3 Emma 706 4 Scott 692 4 Shannon 694 5 James 662 5 Amy 687 6 David 646 6 Sarah 537 7 Connor 621 7 Rachel 523 8 Ross 614 8 Nicole 489 9 Jack 612 9 Megan 482 10 Jordan 605 10 Laura 469 11 Liam 571 11 Kirsty 438 12 Craig 564 12 Hannah 429 13 Michael 542 13 Chloe 412 14 Christopher 524 14 Caitlin 392 15 Kieran 509 15 Danielle 361 16 Lewis 507 16 Jennifer 326 17 Cameron 476 17 Sophie 311 18 Sean 475 18 Samantha 302 19 Mark 455 19 Stephanie 287 20 John 439 20 Erin 282 21 Callum 407 21 Katie 277 22 Jamie 403 22 Claire 267 23 Matthew 400 23 Louise 266 24= Calum 372 24 Eilidh 229 24= Kyle 372 25 Heather 228 26 Thomas 360 26 Gemma 223 27 Dylan 355 27= Lisa 219 28 Steven 325 27= Natalie 219 29 Stuart 320 29 Nicola 218 30 Robert 318 30 Emily 213 31 Alexander 301 31 Ashleigh 208 32= Adam 292 32 Jade 201 32= Darren 292 33 Hayley 199 34 Paul 280 34 Melissa 192 35 Fraser 275 35 Lucy 191 36 William 250 36 Kayleigh 184 37 Stephen 247 37 Rachael 178 38 Lee 220 38 Holly 177 39 Grant 215 39 Ashley 163 40 Declan 189 40 Zoe 162 41= Dean 186 41 Jessica 161 41= Jonathan 186 42 Aimee 157 41= Shaun 186 43 Robyn 154 44 Conor 184 44 Natasha 150 45 Joshua 171 45 Victoria 143 46 Nathan 168 46= Courtney 135 47 Gary 167 46= Jodie 135 48 Aaron -

Gaelic Society Collection 3 Publication Control Classmark Author Title, Part No

A B C D E F G H 1 2 Gaelic Society Collection 3 Publication Control Classmark Author Title, part no. & title Barcode 4 date number (Dewey) A B C. : ann teagasg Criosdiugh, nios achamaire do reir ceisd & 1838 q8179079 238 38011086142968 5 freagradh ai A' Charraig : leabhar bliadhnail eaglais bhearnaraigh 1971 0950233102 285.24114 38011030517448 6 A' Charraig : leabhar bliadhnail eaglais bhearnaraigh 1971 0950233102 285.24114 38011086358515 7 A' Charraig : leabhar bliadhnail eaglais bhearnaraigh 1971 0950233102 285.24114 38011086358523 8 A'Choisir-chiuil : the St.Columba collection of Gaelic songs arranged for 1983 0901771724 891.63 38011030517331 9 pa A'chòmdhail cheilteach eadarnàiseanta : Congress 99. - Glaschu : 26-31 2000 M0001353HL 891.63 38011000710015 10 July A collection of Highland rites and customes / copied by Edward Lhuyd 1975 0859910121 390.941 38011000004195 11 from th A collection of Highland rites and customes / copied by Edward Lhuyd 1975 0859910121 390.941 38011086392324 12 from th A collection of the vocal airs of the Highlands of Scotland : 1996 1871931665 788.95 38011086142927 13 communicated a A Companionto Scottish culture / edited by David Daiches 1981 0713163445 941.11 38011086393645 14 A History of the Scottish Highlands, Highland clans and Highland 1875 x3549092 941.15 38011086358366 15 regiments. Ainmean aìte = Place names 1991 095164193x 491.63 38011050956930 16 Ainmeil an eachraidh : iomradh air dusan ainmeil ann an caochladh 1997 1871901413 920.0411 38011097413804 17 sheòrsacha Aithghearradh teagasg Chriosta : le aonta nan Easbuig ro-urramach 1902 q8177241 232.954 38011086340042 18 Easbuig Ab A B C D E F G H Alba [map]. - 1:1,000,000 1972 M0003560HL 912 38011030517398 19 Albyn's anthology : or, a select collection of the melodies & local poetry p. -

GLA 02 First Names

First Names (Ainmean Baistidh - Christian Names) Bold means checked in Am Faclair Beag, bold and underlined checked in Speaking Our Language, underlined from other sources. *From: Clans and tartans of Scotland, Robert Bain. Another source of names: http://www.namenerds.com/scottish/lists.html - A - Adam, Àdhamh Albert, Albert Alexander, Alastair, Ailig Allan, Alan, Ailean Alpin, Ailpein* Andrew, Anndra, (Aindrea)* Angus, Aonghas Archibald, Gilleasbaig, (Gilleasbuig)* Archie, Eàirdsidh Arthur, Artair Aulay, Amhladh* Agnes (Winifred), Ùna Alice, Aileas, (Ailis)* Amelia (Emily), Aimil, Aimili* Angelica, Aingealag Ann, Anna, Annag Annabella, Anabladh* - B - Barry, Barra* Bartholomew, Parlan* Benjamin, Beathan* Bernard, Bearnard* Barbara, Barabal, Barabara* Beatrice, Beitiris Bessie, Beasag,Ealasaid* Betsy, Betty, Beitidh Beth, Beatrice, Rebecca, Becky, Sophia, Sophie, Bethia, Beathag Bridgit, Brìghde, Bride - C - Page "1 Callum, Malcolm, Calum Charles, Teàrlach Christopher(?), Christian, Crìstean, Gillecriosd* Colin, Cailean Coll, Colla* Conall, Connull* Catherine, Katherine, Kathryn, Catrìona Cecilia, Celia, Sheila, Sìle, Sìleas Chrissie, Criosaidh Christine, Christina, Cairistìona Clara, Clare, (Sara(h)), Sorcha - D - Daniel, Danny, Dànaidh David, Davy, Daibhidh Dermid, Diarmad* Dennis, Donnachadh (Irish) Donald, Dòmhnall (Dómhnull)* Donny, Donaidh, Dòmhnallan Douglas, Dùghlas Dughald, Dougal, Dùghall Duncan, Donnchadh (Donnochadh)* Diana, Diana* Dolly, Doileag Dora, DoireannI Dorcas, Deporodh* Dorothy, Diorbhail, Dearbhail, Diorbhorgail*