Gaelic Names of Pibrochs: a Classification1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DRAFT Pitch and Facility Strategy

Orkney Island Council Sports Facilities and Playing Pitch Strategy Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1 2.METHODOLOGY 10 3. ASSESSMENT AND ANALYSIS SUMMARY – PITCH SPORTS 16 4. ASSESSMENT AND ANALYSIS SUMMARY – OTHER OUTDOOR SPORTS AND ACTIVITIES 33 5. ASSESSMENT AND ANALYSIS SUMMARY - INDOOR FACILITIES 41 6.CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS Orkney Island Council Sports Facilities and Playing Pitch Strategy Appendices 1 STUDY CONSULTEES 2 STRATEGY CONTEXT 3 METHODOLOGY IN DETAIL 4 DEMAND AUDIT TABLE 5 SUPPLY AUDIT TABLE 6 PPM MODEL ANALYSIS 7 MAPS Orkney Island Council Sports Facilities and Playing Pitch Strategy Maps Map 1 All Playing Pitch Sites Map 2 All Playing Pitch Sites by Pitch Type Map 3 All Playing Pitch Sites by Pitch Quality Map 4 All Swimming Pools Map 5 All Sports Halls Map 6 All Fitness Suites Orkney Island Council Sports Facilities and Playing Pitch Strategy Executive Summary Strategic Leisure, part of the Scott Wilson Group, was commissioned by Orkney Islands Council (OIC) in December 2010 to develop a Sports Facilities and Pitch Strategy. This report details the findings of the research and assessment undertaken and the recommendations made on the basis of this evidence. The recommendations provide the strategy for the future provision of sports pitches, indoor and outdoor sports facilities, guide management and operation and provide a framework for funding and investment decisions. Aims, Objectives and Strategic Scope The aim of the study is to produce a robust, well-evidenced and achievable Sports Facility and Pitch Strategy for OIC, which takes account of the demand for, and provision of, indoor and outdoor sport and leisure facilities that are readily available for community activities, with an accompanying Playing Pitch Strategy. -

SCQF Level 6 Bagpipes Practical

Z The Royal Scottish Pipe Band Association Pipe Band College Certification Education Guidelines PDQB CERTIFICATE - SCQF 6 Bagpipes This guide is intended for both Students and Instructors. It must be read in conjunction with SCQF 6 Bagpipes Syllabus to ensure all aspects are covered. Refer www.pdqb.org. It is strongly recommended that all students sitting this level have access to the RSPBA Structured Learning Books. It is also recommended to purchase The College of Piping Tutor 4 – Piobaireachd be purchased. It is therefore important that Instructors use these recommended books as their main source material. The RSPBA Structured Learning Books are available free from the RSPBA Pipe Band College :- https://www.rspba.org/ Obtain College of Piping Tutor 4 Knowledge of SCQF 2 through 5 are essential for SCQF 6. Students who start at SCQF 6 may be required to prove competency of prior levels by the Examiner. Be prepared for this. Theory Aspects: • Write bars of a monotone rhythm in various combinations e.g. Compound Duple time / Cut Common time / Common time etc. And be able to consider rests in the combinations and ensure each bar has different combination of note values. • Explain the accent pattern in reels and describe two important factors in reel playing – could be any type of tune – say Reel or Strathspey etc– accent pattern - Simple Duple Time meaning 2 beats in the Bar SW for reel or Simple Quadruple Time SWMW for Strathspey etc. – important factors in playing different types of tunes – discuss this e.g. good technique, appropriate tempo, decision of round or dot cut etc. -

Bartlett, T. (2020) Time, the Deer, Is in the Wood: Chronotopic Identities, Trajectories of Texts and Community Self-Management

Bartlett, T. (2020) Time, the deer, is in the wood: chronotopic identities, trajectories of texts and community self-management. Applied Linguistics Review, (doi: 10.1515/applirev-2019-0134). This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/201608/ Deposited on: 24 October 2019 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Tom Bartlett Time, the deer, is in the wood: Chronotopic identities, trajectories of texts and community self-management Abstract: This paper opens with a problematisation of the notion of real-time in discourse analysis – dissected, as it is, as if time unfolded in a linear and regular procession at the speed of speech. To illustrate this point, the author combines Hasan’s concept of “relevant context” with Bakhtin’s notion of the chronotope to provide an analysis of Sorley MacLean’s poem Hallaig, with its deep-rootedness in space and its dissolution of time. The remainder of the paper is dedicated to following the poem’s metamorphoses and trajectory as it intertwines with Bartlett’s own life and family history, creating a layered simultaneity of meanings orienting to multiple semio-historic centres. In this way the author (pers. comm.) “sets out to illustrate in theory, text analysis and (self-)history the trajectories taken by texts as they cross through time and space; their interconnectedness -

NOTING the TRADITION an Oral History Project from the National Piping Centre

NOTING THE TRADITION An Oral History Project from the National Piping Centre Interviewee Professor Roddy Cannon Interviewer James Beaton Date of Interview 30 th November 2012 This interview is copyright of the National Piping Centre Please refer to the Noting the Tradition Project Manager at the National Piping Centre, prior to any broadcast of or publication from this document. Project Manager Noting The Tradition The National Piping Centre 30-34 McPhater Street Glasgow G4 0HW [email protected] Copyright, The National Piping Centre 2012 This is James Beaton for ‘Noting the Tradition.’ I’m here in the National Piping Centre with Professor Roddy Cannon, piper, piping historian and researcher, and also professionally a scientist. It’s St Andrew’s Day 2012 and we’re going to be speaking really about Roddy’s life and times in piping. Roddy, good morning and welcome. Good morning. Good morning. It’s always good to be back. Well, it’s nice to see you here and it’s nice to have you back. I come here on averageabout once a year these days. I give a number of classes and I talk to your students and I talk to the staff and I talk to you and it’s wonderful. Well, it’s nice to have you here. The thing that strikes me very much about your classes is that they’re so different from one year to the next. Some sit quietly and listen, some of them join the debate vigorously, and very occasionally I get confuted by counter arguments and that’s what I like best. -

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY of Macdhubhsith

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY OF MacDHUBHSITH ― MacDUFFIE CLAN (McAfie, McDuffie, MacFie, MacPhee, Duffy, etc.) VOLUME 2 THE LANDS OF OUR FATHERS PART 2 Earle Douglas MacPhee (1894 - 1982) M.M., M.A., M.Educ., LL.D., D.U.C., D.C.L. Emeritus Dean University of British Columbia This 2009 electronic edition Volume 2 is a scan of the 1975 Volume VII. Dr. MacPhee created Volume VII when he added supplemental data and errata to the original 1792 Volume II. This electronic edition has been amended for the errata noted by Dr. MacPhee. - i - THE LIVES OF OUR FATHERS PREFACE TO VOLUME II In Volume I the author has established the surnames of most of our Clan and has proposed the sources of the peculiar name by which our Gaelic compatriots defined us. In this examination we have examined alternate progenitors of the family. Any reader of Scottish history realizes that Highlanders like to move and like to set up small groups of people in which they can become heads of families or chieftains. This was true in Colonsay and there were almost a dozen areas in Scotland where the clansman and his children regard one of these as 'home'. The writer has tried to define the nature of these homes, and to study their growth. It will take some years to organize comparative material and we have indicated in Chapter III the areas which should require research. In Chapter IV the writer has prepared a list of possible chiefs of the clan over a thousand years. The books on our Clan give very little information on these chiefs but the writer has recorded some probable comments on his chiefship. -

Etymology of the Principal Gaelic National Names

^^t^Jf/-^ '^^ OUTLINES GAELIC ETYMOLOGY BY THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, Stirwng f ETYMOLOGY OF THK PRINCIPAL GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES |'( I WHICH IS ADDED A DISQUISITION ON PTOLEMY'S GEOGRAPHY OF SCOTLAND B V THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, STIRLING 1911 PRINTKD AT THE " NORTHERN OHRONIOLB " OFFICE, INYBRNESS PREFACE The following Etymology of the Principal Gaelic ISTational Names, Personal Names, and Surnames was originally, and still is, part of the Gaelic EtymologicaJ Dictionary by the late Dr MacBain. The Disquisition on Ptolemy's Geography of Scotland first appeared in the Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, and, later, as a pamphlet. The Publisher feels sure that the issue of these Treatises in their present foim will confer a boon on those who cannot have access to them as originally published. They contain a great deal of information on subjects which have for long years interested Gaelic students and the Gaelic public, although they have not always properly understood them. Indeed, hereto- fore they have been much obscured by fanciful fallacies, which Dr MacBain's study and exposition will go a long way to dispel. ETYMOLOGY OF THE PRINCIPAI, GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES ; NATIONAL NAMES Albion, Great Britain in the Greek writers, Gr. "AXfSiov, AX^iotv, Ptolemy's AXovlwv, Lat. Albion (Pliny), G. Alba, g. Albainn, * Scotland, Ir., E. Ir. Alba, Alban, W. Alban : Albion- (Stokes), " " white-land ; Lat. albus, white ; Gr. dA</)os, white leprosy, white (Hes.) ; 0. H. G. albiz, swan. -

A History of the Lairds of Grant and Earls of Seafield

t5^ %• THE RULERS OF STRATHSPEY GAROWNE, COUNTESS OF SEAFIELD. THE RULERS OF STRATHSPEY A HISTORY OF THE LAIRDS OF GRANT AND EARLS OF SEAFIELD BY THE EARL OF CASSILLIS " seasamh gu damgean" Fnbemess THB NORTHERN COUNTIES NEWSPAPER AND PRINTING AND PUBLISHING COMPANY, LIMITED 1911 M csm nil TO CAROLINE, COUNTESS OF SEAFIELD, WHO HAS SO LONG AND SO ABLY RULED STRATHSPEY, AND WHO HAS SYMPATHISED SO MUCH IN THE PRODUCTION OP THIS HISTORY, THIS BOOK IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR. PREFACE The material for " The Rulers of Strathspey" was originally collected by the Author for the article on Ogilvie-Grant, Earl of Seafield, in The Scots Peerage, edited by Sir James Balfour Paul, Lord Lyon King of Arms. A great deal of the information collected had to be omitted OAving to lack of space. It was thought desirable to publish it in book form, especially as the need of a Genealogical History of the Clan Grant had long been felt. It is true that a most valuable work, " The Chiefs of Grant," by Sir William Fraser, LL.D., was privately printed in 1883, on too large a scale, however, to be readily accessible. The impression, moreover, was limited to 150 copies. This book is therefore published at a moderate price, so that it may be within reach of all the members of the Clan Grant, and of all who are interested in the records of a race which has left its mark on Scottish history and the history of the Highlands. The Chiefs of the Clan, the Lairds of Grant, who succeeded to the Earldom of Seafield and to the extensive lands of the Ogilvies, Earls of Findlater and Seafield, form the main subject of this work. -

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-Names and Society: Analysis of the Medieval Districts of Forsa and Moloros in the Parish of Torosay, Mull

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-names and society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8224/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Settlement-Names and Society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. Alasdair C. Whyte MA MRes Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Celtic and Gaelic | Ceiltis is Gàidhlig School of Humanities | Sgoil nan Daonnachdan College of Arts | Colaiste nan Ealain University of Glasgow | Oilthigh Ghlaschu May 2017 © Alasdair C. Whyte 2017 2 ABSTRACT This is a study of settlement and society in the parish of Torosay on the Inner Hebridean island of Mull, through the earliest known settlement-names of two of its medieval districts: Forsa and Moloros.1 The earliest settlement-names, 35 in total, were coined in two languages: Gaelic and Old Norse (hereafter abbreviated to ON) (see Abbreviations, below). -

Erin and Alban

A READY REFERENCE SKETCH OF ERIN AND ALBAN WITH SOME ANNALS OF A BRANCH OF A WEST HIGHLAND FAMILY SARAH A. McCANDLESS CONTENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART I CHAPTER I PRE-HISTORIC PEOPLE OF BRITAIN 1. The Stone Age--Periods 2. The Bronze Age 3. The Iron Age 4. The Turanians 5. The Aryans and Branches 6. The Celto CHAPTER II FIRST HISTORICAL MENTION OF BRITAIN 1. Greeks 2. Phoenicians 3. Romans CHAPTER III COLONIZATION PE}RIODS OF ERIN, TRADITIONS 1. British 2. Irish: 1. Partholon 2. Nemhidh 3. Firbolg 4. Tuatha de Danan 5. Miledh 6. Creuthnigh 7. Physical CharacteriEtics of the Colonists 8. Period of Ollaimh Fodhla n ·'· Cadroc's Tradition 10. Pictish Tradition CHAPTER IV ERIN FROM THE 5TH TO 15TH CENTURY 1. 5th to 8th, Christianity-Results 2. 9th to 12th, Danish Invasions :0. 12th. Tribes and Families 4. 1169-1175, Anglo-Norman Conquest 5. Condition under Anglo-Norman Rule CHAPTER V LEGENDARY HISTORY OF ALBAN 1. Irish sources 2. Nemedians in Alban 3. Firbolg and Tuatha de Danan 4. Milesians in Alban 5. Creuthnigh in Alban 6. Two Landmarks 7. Three pagan kings of Erin in Alban II CONTENTS CHAPTER VI AUTHENTIC HISTORY BEGINS 1. Battle of Ocha, 478 A. D. 2. Dalaradia, 498 A. D. 3. Connection between Erin and Alban CHAPTER VII ROMAN CAMPAIGNS IN BRITAIN (55 B.C.-410 A.D.) 1. Caesar's Campaigns, 54-55 B.C. 2. Agricola's Campaigns, 78-86 A.D. 3. Hadrian's Campaigns, 120 A.D. 4. Severus' Campaigns, 208 A.D. 5. State of Britain During 150 Years after SeveTus 6. -

Scottish Naming Customs Craig L

Scottish Naming Customs Craig L. Foster AG® [email protected] Origins of Scottish Surnames Surnames are said to have begun to be used by Scottish nobility at the direction of King Malcolm Ceannmor in about 1061. William L. Kirk, Jr. “Introduction to the Derivation of Scottish Surnames,” Clan Macrae (1992), http://www.clanmacrae.ca/documents/names.htm “In some Highland areas, though, fixed surnames did not become the norm until the 18th century, and in parts of the Northern Isles until the 19th century.” “Surnames,” ScotlandsPeople, https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/guides/surnames Types of Scottish Surnames Location-Based Surnames Some people were named for localities. For example, the surname “Murray from the lands of Moray, and Ogilvie, which, according to Black, derives from the barony of Ogilvie in the parish of Glamis, Angus. Tenants might in turn assume, or be given, the name of their landlord, despite having no kinship with him.” Sometimes surnames referred to a specific topographical feature of the landscape such as a river, a loch, a hill, etc. Some examples might include: Names that contain 'kirk' (as in Kirkland, or Selkirk) which means 'church' in Gaelic; 'Muir' or names that contain it (means 'moor' in Gaelic); A name which has 'Barr' in it (this means 'hilltop' in Gaelic). “Surnames,” ScotlandsPeople, https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/guides/surnames Occupational Surnames A significant amount of surnames come from occupations. So a smith became known as Smith or Gow (Gaelic for smith), a tailor became Tailor/Taylor, a baker was Baxter, a weaver was Webster, etc. “Surnames,”ScotlandsPeople, https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/guides/surnames Descriptive Surnames “Nicknames were 'descriptional' ie. -

Spring 2015 Vol. 44, No. 1 Table of Contents

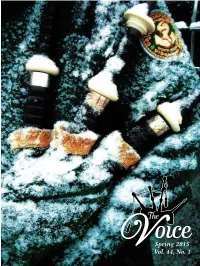

Spring 2015 Vol. 44, No. 1 Table of Contents 4 President’s Message Music 5 Editorial 33 Jimmy Tweedie’s Sealegs 6 Letters to the Editor 43 Report for the Reviews Executive Secretary 34 Review of Gibson Pipe Chanter Spring 2015 35 The Campbell Vol. 44, No. 1 Basics Tunable Chanter 9 Snare Basics: Snare FAQ THE VOICE is the official publication of the Eastern United 11 Bass & Tenor Basics: Semiquavers States Pipe Band Association. Writing a Basic Tenor Score 35 The Making of the 13 Piping Basics: “Piob-ogetics” Casco Bay Contest John Bottomley 37 Pittsburgh Piping EDITOR [email protected] Features Society Reborn 15 Interview Shawn Hall 17 Bands, Games Come Together Branch Notes ART DIRECTOR 19 Willie Wows ‘Em 39 Southwest Branch [email protected] 21 The Last Happy Days – 39 Metro Branch Editorial Inquiries/Letters the Great Highland Bagpipe 40 Ohio Valley Branch THE VOICE in JFK’s Camelot 41 Northeast Branch [email protected] ADVERTISING INQUIRIES John Bottomley [email protected] THE VOICE welcomes submissions, news items, and ON THE COVER: photographs. Please send your Derek Midgley captured the joy submissions to the email above. of early St. Patrick’s parades in the northeast with this photo of Rich Visit the EUSPBA online at www.euspba.org Harvey’s pipe at the Belmar NJ event. ©2014 Eastern United States Pipe Band EUSPBA MEMBERS receive a subscription to THE VOICE paid for, in part, Association. All rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced or transmitted by their dues ($8 per member is designated for THE VOICE). -

Gaelic – What Would Success Look Like?

Alba 2030: Gaelic – what would success look like? Programme 09:00 Registration, tea and coffee 10:00 Welcome/opening remarks: Rt Hon Ken Macintosh MSP, Presiding Officer and Futures Forum Chair 10:05 Keynote contribution: Professor Wilson McLeod, University of Edinburgh 10:25 The Future for Gaelic: Panel discussion with Wilson McLeod, Mary Ann Kennedy and Tadhg Ó hIfearnáin. 11.10 Coffee break 11.25 Workshops 12.45 Feedback 12.55 Thanks/closing remarks 13:00 Networking lunch 14.00 Event finishes Speaker biographies Professor Wilson McLeod is Professor of Gaelic at the University of Edinburgh. He acts as director of research on Celtic and Scottish Studies, with research interests including language policy and planning issues in Scotland; language legislation and language rights; and the cultural politics of Scottish and Irish Gaelic literature. Wilson is a regular media commentator on the role of the Gaelic language in Scotland. Mary Ann Kennedy is a Scottish musician, writer, composer, broadcaster and music producer. She was born and brought up in Glasgow in a Gaelic- speaking household at the heart of the city’s language activism and development in the 1970s and 80s: her mother Dr Kenna Campbell MBE is a prominent cultural tradition-bearer and educator, and her father Alasdair was the documentary voice in print of the city’s traditional Gaelic and Highland communities. She is co-director of her own creative business, Watercolour Music, in the West Highlands, and has a particular passion for new writing and non-traditional forms of Gaelic-language music. She previously spent several years in BBC News, ultimately running the Gaelic-language news service.