Gender Gaps Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf | 336.56 Kb

RAPID EMERGENCY ASSESSMENT AND COORDINATION TEAM (REACT) Floods in Khatlon: 7 – 13 May 2021 Situation Report # 1 (as of 14 May 2021) Highlights - Over 12 mudflows and landslides have been reported during the period of 7 – 13 May 2021. - Mudflows caused the death of 9 people. - Over 70 households are left homeless. - Large number of cattle has been lost and agricultural crops destroyed. - Mudflows caused disruptions to the livelihoods of around 22,000 people Situation Overview The torrential rains of 7 – 12 May 2021 triggered floods, landslides and mudflows in many of the country’s districts. The largest number of losses and destructions are faced by districts and cities of Khatlon province. Disasters affected following cities and districts: Kulob city and districts of Shamsiddini Shohin, Qushoniyon, Dangara, Yovon, Khuroson, Dusti, Vaksh, Muminobod and Jomi (please refer to Map below). CoES reports that disasters caused the death 9 people. Very preliminary estimates indicate that 74 households were left homeless and houses of another 270 households were damaged to different extent. Very modest estimations indicate damages caused by disasters to private and social infrastructure caused disruptions to the livelihoods of around 22,000 people. Government of Tajikistan activated an Inter-Agency Commission on Emergency Situations (Commission) in each disaster affected district, which fully facilitates the response operations. Furthermore, Emergency Operations Centers (Shtab) have been set up in each disaster affected district, which collects and analyzes relevant information and coordinates the response activities. Up to date, general response actions in every district include: search and rescue, evacuation of population from risk zones, constant disinfection of the affected territories, debris removal, assessment of damages and needs, registration of affected population, restoration of communal services, collection and distribution of immediate relief assistance, as well as recovery planning. -

Application of Space Based Technologies for Disaster Risk Assessment at the Level of Communities A. Shomahmadov

Asian Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction January 23 rd 2013 , Kobe, Japan Application of space based technologies for Disaster Risk Assessment at the level of communities A. Shomahmadov Head of the Information Management and Analytical Center (IMAC) of the Committee of ES and CD, Tajikistan SSpacepace Based Technologies Application GIS mapping and application of geospatial information systems, which have become widespread and recognized in Tajikistan, allow to use innovative and effective approaches for the analysis of the information about disasters and solve tasks on their prevention and risk reduction. They play an especially important role for decision-making in socio- economic, economic, political and ecological spheres of development, disaster and natural resources management. A lot of agencies and departments are getting more and more concerned with the lack of qualified specialists who can effectively use GIS technologies and geospatial information systems for scientific research and decision-making. 1 SSpacepace Based Technologies Application Recent important achievements of the GIS technologies and remote sensing: 1. Monitoring and Early Warning System was installed in 2004 at the lake Sarez and it conducts the following kinds of measurements: Surface displacements on the body of the Usoi Landslide Dam; Registration of strong movements during earthquakes; Water level of the lake and maximal wave height; The water discharge of the Murghab river; Turbidity of the drain flow from the lake; Meteorological data. Components of the Monitoring System are used for the activation of the warning system and they are integrated into EarlyWarning System. The transmission of all data, warning signals and remote supervision over the system is carried out through the satellite system INMARSAT, or locally, through cables on short distances. -

White Gold Or Women's Grief the Gendered Cotton

‘White Gold’ or Women’s Grief? The Gendered Cotton of Tajikistan – Oxfam GB October 2005 I. xecutive ummary 1 E S kept in the dark concerning their labour rights Contrary to dominant institutional and land rights; rural communities are not belief, cotton in Tajikistan, especially given its given any details about the extend of the farm present production structure, is not a cotton debt (estimated on a whole to have ‘strategic’ commodity; is highly inequitable in surpassed US$280 million by July 2005); for its distribution of financial gains in favour of nearly all female cotton workers, major investors rather than the majority-female farm incentives to work is the opportunity to collect workers; exploits the well-being and labour the meagre cotton picking earnings (about rights of children and rural households; leads US$0.03/kg) and the reward of collecting the ghuzapoya to rampant indebtedness of farms; induces end-of-season dried cotton stalks ( ) food insecurity, hunger, and poverty; is used as fuel, bartered or sold; the conditions socially destructive, causing widespread of many farms and farm workers is not unlike migration and dislocation of families; damages ‘bonded labour’ and ‘financial servitude’; not the micro and macro environments, cotton is thus a strategic commodity for contradicting principles of sustainable Tajikistan nor is it a ‘cash crop’ for rural economic development; and if not mitigated women and their households, with the crop of will likely lead to social and economic choice for the far majority being food crops aggravations. such as wheat, corn, potatoes and vegetables. A rapid qualitative study was con- The following advocacy and program- ducted during a three week period in March ming recommendations are presented to and April 2005 in the southern Khatlon Oxfam GB on the issue of gender and cotton province of Tajikistan and the capital city, production in Tajikistan. -

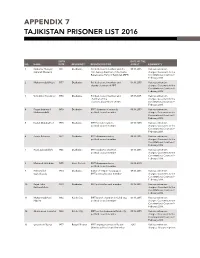

Appendix 7 Tajikistan Prisoner List 2016

APPENDIX 7 TAJIKISTAN PRISONER LIST 2016 BIRTH DATE OF THE NO. NAME DATE RESIDENCY RESPONSIBILITIES ARREST COMMENTS 1 Saidumar Huseyini 1961 Dushanbe Political council member and the 09.16.2015 Various extremism (Umarali Khusaini) first deputy chairman of the Islamic charges. Case went to the Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 2 Muhammadalii Hayit 1957 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.16.2015 Various extremism deputy chairman of IRPT charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 3 Vohidkhon Kosidinov 1956 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.17.2015 Various extremism chairman of the charges. Case went to the elections department of IRPT Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 4 Fayzmuhammad 1959 Dushanbe IRPT chairman of research, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Muhammadalii political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 5 Davlat Abdukahhori 1975 Dushanbe IRPT foreign relations, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 6 Zarafo Rahmoni 1972 Dushanbe IRPT chairman advisor, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 7 Rozik Zubaydullohi 1946 Dushanbe IRPT academic chairman, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 8 Mahmud Jaloliddini 1955 Hisor District IRPT chairman advisor, 02.10.2015 political council member 9 Hikmatulloh 1950 Dushanbe Editor of “Najot” newspaper, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Sayfullozoda IRPT political council member charges. -

World Bank Document

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: PAD3028 INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED GRANT Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 41.80 MILLION (US$ 58 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN FOR A Public Disclosure Authorized RURAL WATER SUPPLY AND SANITATION PROJECT February 4, 2019 Water Global Practice Europe And Central Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective December 31, 2018) Currency Unit = SDR 0.719 = US$1 US$ 1.391 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 Regional Vice President: Cyril E Muller Country Director: Lilia Burunciuc Senior Global Practice Director: Jennifer Sara Practice Manager: David Michaud Task Team Leader(s): Sana Kh.H. Agha Al Nimer, Farzona Mukhitdinova ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB Asian Development Bank AF Additional Financing APA Alternate Procurement Arrangements CERC Contingent Emergency Response Component CPF Country Partnership Strategy CSC Community Scorecard DA Designated Account DFIL Disbursement and Financial Information Letter EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework ESMPs Environmental and Social Management Plans FCV Fragility, Conflict and Violence FI Financial Intermediaries FM Financial Management -

Tajikistan 2016 Human Rights Report

TAJIKISTAN 2016 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Tajikistan is an authoritarian state dominated politically by President Emomali Rahmon and his supporters. The constitution provides for a multiparty political system, but the government has historically obstructed political pluralism and continued to do so during the year. A constitutional amendment approved in a national referendum on May 22 outlawed non-secular political parties and removed any limitation on President Rahmon’s terms in office as the “Leader of the Nation,” allowing him to further solidify his rule. Civilian authorities only partially maintained effective control over security forces. Officials in the security services and elsewhere in the government acted with impunity. The most significant human rights problems included citizens’ inability to change their government through free and fair elections; torture and abuse of detainees and other persons by security forces; repression, increased harassment, and incarceration of civil society and political activists; and restrictions on freedoms of expression, media, and the free flow of information, including through the repeated blockage of several independent news and social networking websites. Other human rights problems included torture in the military; arbitrary arrest; denial of the right to a fair trial; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; prohibition of international monitors’ access to prisons; poor religious freedom conditions; violence and discrimination against women; limitations on worker rights; and trafficking in persons, including sex and labor trafficking. There were very few prosecutions of government officials for human rights abuses. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. Arbitrary Deprivation of Life and other Unlawful or Politically Motivated Killings While the law prohibits extrajudicial killings by government security forces, there were several reports that the government or its agents committed arbitrary or unlawful killings. -

Tajikistan: Rural Residents Complain About Poor Conditions of the Healthcare Centers (Photoreport)

Tajikistan: Rural Residents Complain About Poor Conditions of the Healthcare Centers (Photoreport) Healthcare centers in rural areas of Tajikistan are in disrepair, crumbled or unsuitable for receiving patients, and remain one of the acute problems. Follow us on LinkedIn The authorities claim that almost all healthcare centers (previously they were called ‘rural outpatient clinics’ – Ed.) are restored or renovated, but residents of remote villages and doctors who work there complain about various difficulties in healthcare. Khatlon Region: Healthcare Centers Are Crumbling Lolazor-2 village of Mashal jamoat is located 50 kilometers from the regional center of Vakhsh district (108 km south of Dushanbe). For more than 20 years, its residents were not able to obtain a good health center. About 70 families live in this village. Gulmahmad Kishvarov, the village doctor, told CABAR.asia that it is very difficult to see patients in the current conditions in which he works. Tajikistan: Rural Residents Complain About Poor Conditions of the Healthcare Centers (Photoreport) The healthcare center of Lolazor-2 village of Vakhsh district is located in the cargo container. Photo: CABAR.asia “There is no medical center in the village, I work in a cargo container. Imagine the conditions inside. The patient comes; he has nowhere to lie down, it is impossible to put a drip. It is cold in winter, hot in summer. Of course, I will do my job in any case, but I would like the conditions to be better,” says Gulmahmad Kishvarov. According to him, the villagers addressed the authorities requesting to build a new healthcare center for them, but so far, there is no reply. -

Socio-Political Change in Tajikistan

Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades des Doktors der Philosophie Dissertation for the Obtainment of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Universität Hamburg Fachbereich Sozialwissenschaften Institut für Politikwissenschaft University of Hamburg Faculty of Social Sciences Institute for Political Science Socio-Political Change in Tajikistan The Development Process, its Challenges Since the Civil War and the Silence Before the New Storm? By Gunda Wiegmann Primary Reviewer: Prof. Rainer Tetzlaff Secondary Reviewer: Prof. Frank Bliss Date of Disputation: 15. July 2009 1 Abstract The aim of my study was to look at governance and the extent of its functions at the local level in a post-conflict state such as Tajikistan, where the state does not have full control over the governance process, particularly regarding the provision of public goods and services. What is the impact on the development process at the local level? My dependent variable was the slowed down and regionally very much varying development process at the local level. My independent variable were the modes of local governance that emerged as an answer to the deficiencies of the state in terms of providing public goods and services at the local level which led to a reduced role of the state (my intervening variable). Central theoretic concepts in my study were governance – the processes, mechanisms and actors involved in decision-making –, local government – the representation of the state at the local level –, local governance – the processes, mechanisms and actors involved in decision- making at the local level and institutions – the formal and informal rules of the game. In the course of my field research which I conducted in Tajikistan in the years 2003/2004 and in 2005 I found that the state does not provide public goods and services to the local population in a sufficient way. -

Feed the Future Tajikistan Health and Nutrition Activity

FEED THE FUTURE TAJIKISTAN HEALTH AND NUTRITION ACTIVITY Annual Progress Report October 2017 to September 2018 Submitted October 30, 2018 Table of contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................ 4 Activity Implementation Summary ....................................................................... 5 IR 1: IMPROVED QUALITY OF HEALTH CARE SERVICES FOR MNCH ...................... 7 Outcome 1.1: Improved quality of health care services being provided in the FTF ZOI ................ 7 Outcome 1.2: Improved patient access to health care services in the FTF ZOI due to improved quality .................................................................................................... 14 Outcome 1.3: Stronger facility and provider networks ................................................................ 18 1.3.1. Hospital-level activities .................................................................................................................. 18 1.3.2. Primary health care activities ......................................................................................................... 19 IR 2: INCREASED ACCESS TO A DIVERSE SET OF NUTRIENT-RICH FOODS ............ 20 Outcome 2.1: Diversified food consumption during the growing season and beyond ............... 20 Outcome 2.2: Nutrition integrated into agriculture-focused programs and linked to value chains supported through FTF activities ....................................................... 23 IR 3: INCREASED PRACTICE -

40046-013: Completion Report

Completion Report Project Number: 40046-013 Loan Number: 2356 April 2015 Tajikistan: Khatlon Province Flood Risk Management Project This document is being disclosed to the public in accordance with ADB’s Public Communications Policy 2011. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit – somoni (TJS) At Project Design At Project Completion (31 August 2007) (6 April 2015) TJS1.00 = $0.29 $0.17 $1.00 = TJS3.44 TJS5.80 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank CES – Committee for Emergency Situations CIS – Chubek irrigation system CPS – country partnership strategy DMF – design and monitoring framework EIRR – economic internal rate of return ha – hectare Hydromet – Agency for Hydrometeorology ICB – international competitive bidding JFPR – Japan Fund for Poverty Reduction km – kilometer MLRWR – Ministry of Land Reclamation and Water Resources NCB – national competitive bidding NGO – nongovernment organization O&M – operation and maintenance PCR – project completion report PIO – project implementation office PMO – project management office PPTA – project preparatory technical assistance SDR – special drawing rights WRM – water resources management GLOSSARY jamoat – administrative unit below the district, comprising a group of villages; also the lowest level of local government administration NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the government and its agencies ends on 31 December. FY before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends, e.g., FY2009 ends on 31 December 2009. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. Vice-President W. Zhang, Operations Group 1 Director General K. Gerhaeusser, Central and West Asia Department (CWRD) Director A. Siddiq, Environment, Natural Resources and Agriculture Division, CWRD Team leader R. Takaku, Senior Water Resources Specialist, CWRD Team members G. -

Women's Entrepreneurship for Empowerment Project Tajikistan

Women’s Entrepreneurship for Empowerment Project Tajikistan ANNUAL REPORT: October 1, 2014 – September 30, 2015 Originally Submitted: October 28, 2015 Revised and Resubmitted: April 30, 2016 THIS ANNUAL REPORT IS MADE POSSIBLE BY THE SUPPORT OF THE AMERICAN PEOPLE THROUGH THE UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT (USAID). THE CONTENTS ARE THE SOLE RESPONSIBILITY OF NABWT AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF USAID OR THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT. Women’s Entrepreneurship for Empowerment TAJIKISTAN ANNUAL REPORT: October 1, 2014 – September 30, 2015 Activity Title: Women’s Entrepreneurship for Empowerment, Tajikistan Agreement Officer: Kerry West Agreement Officer’s Representative: Mukhiddin Nurmatov Project Manager : Farrukh Shoimardonov Sponsoring USAID Office: Economic Development Office Agreement Number: AID-176-A-14-00006 Award Period: October 1, 2014 through September 30, 2017 Contractor: NABWT ( National Association of Business Women of Tajikistan ) Original Date of Publication: October 28, 2015 Revised and Resubmitted: April 30, 2016 Author: Farrukh Shoimardonov THE AUTHORS’ VIEWS EXPRESSED IN THIS PUBLICATION DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT OR THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT Page 2 of 106 Annual Report Year 1 - Women’s Entrepreneurship for Empowerment, Tajikistan implemented by NABWT ( The National Association of Business Women of Tajikistan ) Report Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS .............................................................................................................................. -

Wfp255696.Pdf

Summary of Findings, Methods, and Next Steps Key Findings and Issues Overall, the food security situation was analyzed in 13 livelihood zones for September–December 2012. About 870,277 people in 12 livelihood zones is classified in Phase 3- Crisis. Another 2,381,754 people are classified in Phase 2- Stressed and 2,055,402 in Phase 1- Minimal. In general, the food security status of analyzed zones has relatively improved in the reporting months compared to the previous year thanks to increased remittances received, good rainfall and good cereal production reaching 1.2 million tons, by end 2012, by 12 percent higher than in last season. The availability of water and pasture has also increased in some parts of the country, leading to improvement in livestock productivity and value. Remittances also played a major role in many household’ livelihoods and became the main source of income to meet their daily basic needs. The inflow of remittances in 2012 peaked at more than 3.5 billion USD, surpassing the 2011 record of 3.0 billion USD and accounting for almost half of the country’s GDP. Despite above facts that led to recovery from last year’s prolong and extreme cold and in improvement of overall situation, the food insecure are not able to benefit from it due to low purchasing capacity, fewer harvest and low livestock asset holding. Several shocks, particularly high food fuel prices, lack of drinking and irrigation water in many areas, unavailability or high cost of fertilizers, and animal diseases, have contributed to acute food insecurity (stressed or crisis) for thousands of people.