White Gold Or Women's Grief the Gendered Cotton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Und Leute 22

Vorwort 11 Herausragende Sehenswürdigkeiten 12 Das Wichtigste in Kurze 14 Entfernungstabelle 20 Zeichenlegende 20 LAND UND LEUTE 22 Tadschikistan im Überblick 24 Landschaft und Natur 25 Gewässer und Gletscher 27 Klima und Reisezeit 28 Flora 29 Fauna 32 Umweltprobleme 37 Geschichte 42 Die Anfänge 42 Vom griechisch-baktrischen Reich bis zur Kushan-Dynastie 47 Eroberung durch die Araber und das Somonidenreich 49 Türken, Mongolen und das Emirat von Buchara 49 Russischer Einfluss und >Great Game< 50 Sowjetische Zeit 50 Unabhängigkeit und Burgerkrieg 52 Endlich Frieden 53 Tadschikistan im 21. Jahrhundert 57 Regierung 57 Wirtschaftslage 58 Kritik und Opposition 58 Tourismus 60 Politisches System in Theorie und Praxis 61 Administrative Gliederung 63 Wirtschaft 65 Bevölkerung und Kultur 69 Religionen und Minderheiten 71 Städtebau und Architektur 74 Volkskunst 77 Sprache 79 Literatur 80 Musik 85 Brauche 89 http://d-nb.info/1071383132 Feste 91 Heilige Statten 94 Die tadschikische Küche 95 ZENTRALTADSCHIKISTAN 102 Duschanbe 104 Geschichte 104 Spaziergang am Rudaki-Prospekt 110 Markt und Mahalla 114 Parks am Varzob-Fluss 115 Museen 119 Denkmaler 122 Duschanbe live 128 Duschanbe-Informationen 131 Die Umgebung von Duschanbe 145 Festung Hisor 145 Varzob-Schlucht 148 Romit-Tal 152 Tal des Karatog 153 Wasserkraftwerk Norak 154 Das Rasht-Tal 156 Ob-i Garm 158 Gharm 159 Jirgatol 159 Reiseveranstalter in Zentral tadschikistan 161 DER PAMIR 162 Das Dach der Welt 164 Ein geografisches Kurzportrait 167 Die Bewohner des Pamirs 170 Sprache und Religion 186 Reisen -

Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: TAJIKISTAN January 2007 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Tajikistan (Jumhurii Tojikiston). Short Form: Tajikistan. Term for Citizen(s): Tajikistani(s). Capital: Dushanbe. Other Major Cities: Istravshan, Khujand, Kulob, and Qurghonteppa. Independence: The official date of independence is September 9, 1991, the date on which Tajikistan withdrew from the Soviet Union. Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1), International Women’s Day (March 8), Navruz (Persian New Year, March 20, 21, or 22), International Labor Day (May 1), Victory Day (May 9), Independence Day (September 9), Constitution Day (November 6), and National Reconciliation Day (November 9). Flag: The flag features three horizontal stripes: a wide middle white stripe with narrower red (top) and green stripes. Centered in the white stripe is a golden crown topped by seven gold, five-pointed stars. The red is taken from the flag of the Soviet Union; the green represents agriculture and the white, cotton. The crown and stars represent the Click to Enlarge Image country’s sovereignty and the friendship of nationalities. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early History: Iranian peoples such as the Soghdians and the Bactrians are the ethnic forbears of the modern Tajiks. They have inhabited parts of Central Asia for at least 2,500 years, assimilating with Turkic and Mongol groups. Between the sixth and fourth centuries B.C., present-day Tajikistan was part of the Persian Achaemenian Empire, which was conquered by Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C. After that conquest, Tajikistan was part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, a successor state to Alexander’s empire. -

Tourism in Tajikistan As Seen by Tour Operators Acknowledgments

Tourism in as Seen by Tour Operators Public Disclosure Authorized Tajikistan Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized DISCLAIMER CONTENTS This work is a product of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS......................................................................i The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other INTRODUCTION....................................................................................2 information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. TOURISM TRENDS IN TAJIKISTAN............................................................5 RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS TOURISM SERVICES IN TAJIKISTAN.......................................................27 © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank TOURISM IN KHATLON REGION AND 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: +1 (202) 522-2422; email: [email protected]. GORNO-BADAKHSHAN AUTONOMOUS OBLAST (GBAO)...................45 The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and li- censes, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, PROFILE AND LIST OF RESPONDENTS................................................57 Cover page images: 1. Hulbuk Fortress, near Kulob, Khatlon Region 2. Tajik girl holding symbol of Navruz Holiday 3. -

Download the File

Mediating the Conflict in the Rasht Valley, Tajikistan The Hegemonic Narrative and Anti-Hegemonic Challenges Accepted version of an article published in Central Asian Affairs: Lemon, Edward. " Mediating the Conflict in the Rasht Valley, Tajikistan", Central Asian Affairs 1, 2 (2014): 247-272. Edward Lemon Department of Politics, University of Exeter [email protected] Abstract Between 2009 and 2011 Tajikistan experienced one of the worst bouts of political vio- lence since the end of the country’s civil war. The fighting was concentrated in the Rasht Valley, an area traditionally associated with opposition to the regime. As a result, the government attempted to fix the meaning of the conflict around the signifiers “international terrorism” and “radical Islam.” This framing directly reproduced the regime’s hegemony through legitimating the removal of opponents and contrasting the Tajik “self” with the terrorist “other.” The hegemonic narrative was incomplete and contained inconsistencies. As a result, anti- hegemonic actors attempted to under- mine its legitimacy. Although these critical articulations destabilized the narrative, due to their dispersed and divergent nature, it ultimately maintained its hegemonic position. Keywords Tajikistan – terrorism – Islam – conflict – framing On April 15, 2011, Tajik television displayed graphic images of militants killed by government forces during a special operation. The video contained images of illegal weapons caches, mountain hideouts, bomb-making books, and Islamist motifs. The narrator labeled the militants as “international terrorists” (bain- almilli terroriston). He stated that these men wanted to overthrow the government and enforce an Islamic state based on shari’a law in Tajikistan. Long-time government opponent Mullo Abdullo led the group. -

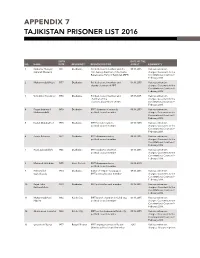

Appendix 7 Tajikistan Prisoner List 2016

APPENDIX 7 TAJIKISTAN PRISONER LIST 2016 BIRTH DATE OF THE NO. NAME DATE RESIDENCY RESPONSIBILITIES ARREST COMMENTS 1 Saidumar Huseyini 1961 Dushanbe Political council member and the 09.16.2015 Various extremism (Umarali Khusaini) first deputy chairman of the Islamic charges. Case went to the Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 2 Muhammadalii Hayit 1957 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.16.2015 Various extremism deputy chairman of IRPT charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 3 Vohidkhon Kosidinov 1956 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.17.2015 Various extremism chairman of the charges. Case went to the elections department of IRPT Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 4 Fayzmuhammad 1959 Dushanbe IRPT chairman of research, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Muhammadalii political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 5 Davlat Abdukahhori 1975 Dushanbe IRPT foreign relations, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 6 Zarafo Rahmoni 1972 Dushanbe IRPT chairman advisor, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 7 Rozik Zubaydullohi 1946 Dushanbe IRPT academic chairman, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 8 Mahmud Jaloliddini 1955 Hisor District IRPT chairman advisor, 02.10.2015 political council member 9 Hikmatulloh 1950 Dushanbe Editor of “Najot” newspaper, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Sayfullozoda IRPT political council member charges. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2011 Foreword

ANNUAL REPORT 2011 FOREWORD 20 years of Mission East Mission East - is a Danish aid organisation - exists to deliver relief and development assistance to vulnerable communities in Eastern Europe and Asia - aims to assist the most vulnerable, making no political, racial, or religious distinction between those in need - is based on Christian values Mission East’s - in 2011 Mission East Ambassador worked in Afghanistan, Mikael Jarnvig Armenia, Nepal, North in North Korea during the fi rst Korea, Pakistan, Romania, food distribution and Tajikistan through in June 2011. direct interventions or in partnership with local organisations 2011 marked the 20th anniversary of Mission string of devastating weather events. These Board East. Established with a mission to meet the food distributions echo back to our earliest Chairman Carsten Wredstrøm needs of vulnerable people in crisis-stricken interventions 20 years ago when we fi rst Karsten Bach countries in Eastern Europe and Asia, brought food aid to Russia and Armenia. Brian Nielsen we have since then impacted the lives of Joachim Nisgaard hundreds of thousands of people in 16 such 2011 also concluded a strategic process in René Hartzner countries, with both emergency aid and long- which we identifi ed two priority sectors in Editors term development interventions. This report our development work: Rural Community Kim Hartzner, outlines the last year of our efforts in seven of Development and Disability & Special Needs. Managing Director these countries where we are currently active. Focusing on improving our competencies Peter Drummond Smith, and capacity in these areas will make us more Operations Director At our jubilee in May, 278 supporters effi cient and increase our impact. -

Formative Research on Infant and Young Child Feeding

FORMATIVE RESEARCH ON INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING Final Report AND MATERNAL NUTRITION 2016 IN TAJIKISTAN Conducted by Dornsife School of Public Health & College of Nursing and Health Professions, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA USA For UNICEF Tajikistan Under Drexel’s Long Term Agreement for Services In Communication for Development (C4D) with UNICEF And Contract # 43192550 January 11 through November 30, 2016 Principal Investigator Ann C Klassen, PhD , Professor, Department of Community Health and Prevention Co-Investigators Brandy Joe Milliron PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Nutrition Sciences Beth Leonberg, MA, MS, RD – Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Nutrition Sciences Graduate Research Staff Lisa Bossert, MPH, Margaret Chenault, MS, Suzanne Grossman, MSc, Jalal Maqsood, MD Professional Translation Staff Rauf Abduzhalilov, Shokhin Asadov, Malika Iskandari, Muhiddin Tojiev This research is conducted with the financial support of the Government of the Russian Federation Appendices : (Available Separately) Additional Bibliography Data Collector Training, Dushanbe, March, 2016 Data Collection Instruments Drexel Presentations at National Nutrition Forum, Dushanbe, July, 2016 cover page photo © mromanyuk/2014 FORMATIVE RESEARCH ON INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING AND MATERNAL NUTRITION IN TAJIKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1: Executive Summary 5 Section 2: Overview of Project 12 Section 3: Review of the Literature 65 Section 4: Field Work Report 75 Section 4a: Methods 86 Section 4b: Results 101 Section 5: Conclusions and Recommendations 120 Section 6: Literature Cited 138 FORMATIVE RESEARCH ON INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING FORMATIVE RESEARCH ON INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING 3 AND MATERNAL NUTRITION IN TAJIKISTAN AND MATERNAL NUTRITION IN TAJIKISTAN SECTION 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction Tajikistan is a mountainous, primarily rural country of approximately 8 million residents in Central Asia. -

Central Asia's Destructive Monoculture

THE CURSE OF COTTON: CENTRAL ASIA'S DESTRUCTIVE MONOCULTURE Asia Report N°93 -- 28 February 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. THE ECONOMICS OF COTTON............................................................................... 2 A. UZBEKISTAN .........................................................................................................................2 B. TAJIKISTAN...........................................................................................................................6 C. TURKMENISTAN ..................................................................................................................10 III. THE POLITICS OF COTTON................................................................................... 12 A. UZBEKISTAN .......................................................................................................................12 B. TAJIKISTAN.........................................................................................................................14 C. TURKMENISTAN ..................................................................................................................15 IV. SOCIAL COSTS........................................................................................................... 16 A. WOMEN AND COTTON.........................................................................................................16 -

SME PRESS REVIEW International Finance Corporation

SME PRESS REVIEW International Finance Corporation Friday, 30 September 2011 In this issue: Feature News EITI development issues discussed in Dushanbe……………………………………………...2 Creating a "One-Stop Shop" for exports and imports will be discussed in Dushanbe……..2 Tajikistan offers very good benefits to investors, expert says…………………………….......3 Investment plan for the development of tax administration in Tajikistan developed...….…3 Interest rates decreased in Tajikistan……………………………………………………….….4 The Government approved the State Commission draft budget for 2012 ……………….….4 Tajik Central Bank attributes fall to USD-TJS exchange rate to external factors…….…....4 The new draft tax code discussed in Dushanbe………………………………………………..5 Other News Cooperation between business communities of Tajikistan and Poland discussed in Dushanbe.5 World encounters second wave of global financial crisis, says CPT leader……………………..6 Tajik delegation attends Euro-Asia economic forum in China…………………………………..6 Tajikistan begins to supply electrical power to Afghanistan……………………………………..7 Paid services to population in Tajikistan amounted to nearly $ 1 billion ………………………7 Joint meeting of the National Council and development partners was held in Dushanbe ….…7 Weighted average interest rate on loans falls 1.3% in Tajikistan…………………………….…8 Six high-ranking Kyrgyz state officials reportedly dismissed for fuel smuggling to Tajikistan.9 More than $ 3.2 million wage arrears in Tajikistan………………………………………………9 News in Brief It is planned to obtain 2.5 tons of gold in Tajikistan in 2011 …………………………………..9 -

Tajikistan 2016 Human Rights Report

TAJIKISTAN 2016 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Tajikistan is an authoritarian state dominated politically by President Emomali Rahmon and his supporters. The constitution provides for a multiparty political system, but the government has historically obstructed political pluralism and continued to do so during the year. A constitutional amendment approved in a national referendum on May 22 outlawed non-secular political parties and removed any limitation on President Rahmon’s terms in office as the “Leader of the Nation,” allowing him to further solidify his rule. Civilian authorities only partially maintained effective control over security forces. Officials in the security services and elsewhere in the government acted with impunity. The most significant human rights problems included citizens’ inability to change their government through free and fair elections; torture and abuse of detainees and other persons by security forces; repression, increased harassment, and incarceration of civil society and political activists; and restrictions on freedoms of expression, media, and the free flow of information, including through the repeated blockage of several independent news and social networking websites. Other human rights problems included torture in the military; arbitrary arrest; denial of the right to a fair trial; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; prohibition of international monitors’ access to prisons; poor religious freedom conditions; violence and discrimination against women; limitations on worker rights; and trafficking in persons, including sex and labor trafficking. There were very few prosecutions of government officials for human rights abuses. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. Arbitrary Deprivation of Life and other Unlawful or Politically Motivated Killings While the law prohibits extrajudicial killings by government security forces, there were several reports that the government or its agents committed arbitrary or unlawful killings. -

Semi-Annual Environmental Monitoring Report

SEMI-ANNUAL ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING REPORT Project No.47181-002 ADB Loan No.3434-TAJ/Grant: No.0498-TAJ Reporting period: July – December 2020 REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN: WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT IN PYANJ RIVER BASIN (Financed by Asian Development Bank) Prepared by BETS Consulting Services Ltd. Bangladesh in association with LLC “Panasia” Ltd. Tajikistan for the Project Implementation Group “Water resources management in Pyanj river basin” under the State institution "Capital and Land reclamation construction" Agency of Land Reclamation and Irrigation under the Government of the Republic of Tajikistan and the Asian Development Bank This environmental monitoring report is a document of the Borrower. The views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of ADB's board of directors, management or staff and may be preliminary. In preparing a Country Program or Strategy, financing a project, or by indicating or referencing a specific territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments regarding the legal or other status of any territory or region. January 2021 1 CONTENT I. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………….5 II. PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND CURRENT ACTIVITY……………………………………6 2.1. Project Description……………………………………………………………………………..6 2.2 Project Location………………………………………………………………………………...7 2.3. Agreements (contracts) for project implementation and management………………...…8 2.4. Project activities during the reporting period……………………………………………….12 2.4.1. Modernization and rehabilitation of irrigation infrastructure in Hamadoni district………13 2.4.2. Modernization and rehabilitation of irrigation infrastructure in Farkhor district………...17 2.4.3. Modernization and rehabilitation of irrigation infrastructure in Vose district…………....23 2.4.4. Construction of the lake-type sediment excluding basin in Hamadoni district…………24 2.4.5. -

Wfp255696.Pdf

Summary of Findings, Methods, and Next Steps Key Findings and Issues Overall, the food security situation was analyzed in 13 livelihood zones for September–December 2012. About 870,277 people in 12 livelihood zones is classified in Phase 3- Crisis. Another 2,381,754 people are classified in Phase 2- Stressed and 2,055,402 in Phase 1- Minimal. In general, the food security status of analyzed zones has relatively improved in the reporting months compared to the previous year thanks to increased remittances received, good rainfall and good cereal production reaching 1.2 million tons, by end 2012, by 12 percent higher than in last season. The availability of water and pasture has also increased in some parts of the country, leading to improvement in livestock productivity and value. Remittances also played a major role in many household’ livelihoods and became the main source of income to meet their daily basic needs. The inflow of remittances in 2012 peaked at more than 3.5 billion USD, surpassing the 2011 record of 3.0 billion USD and accounting for almost half of the country’s GDP. Despite above facts that led to recovery from last year’s prolong and extreme cold and in improvement of overall situation, the food insecure are not able to benefit from it due to low purchasing capacity, fewer harvest and low livestock asset holding. Several shocks, particularly high food fuel prices, lack of drinking and irrigation water in many areas, unavailability or high cost of fertilizers, and animal diseases, have contributed to acute food insecurity (stressed or crisis) for thousands of people.