American Songs Around 1900

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

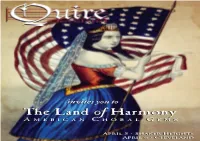

The Land of Harmony a M E R I C a N C H O R a L G E M S

invites you to The Land of Harmony A MERIC A N C HOR A L G EMS April 5 • Shaker Heights April 6 • Cleveland QClevelanduire Ross W. Duffin, Artistic Director The Land of Harmony American Choral Gems from the Bay Psalm Book to Amy Beach April 5, 2014 April 6, 2014 Christ Episcopal Church Historic St. Peter Church shaker heights cleveland 1 Star-spangled banner (1814) John Stafford Smith (1750–1836) arr. R. Duffin 2 Psalm 98 [SOLOISTS: 2, 3, 5] Thomas Ravenscroft (ca.1590–ca.1635) from the Bay Psalm Book, 1640 3 Psalm 23 [1, 4] John Playford (1623–1686) from the Bay Psalm Book, 9th ed. 1698 4 The Lord descended [1, 7] (psalm 18:9-10) (1761) James Lyon (1735–1794) 5 When Jesus wep’t the falling tear (1770) William Billings (1746–1800) 6 The dying Christian’s last farewell (1794) [4] William Billings 7 I am the rose of Sharon (1778) William Billings Solomon 2:1-8,10-11 8 Down steers the bass (1786) Daniel Read (1757–1836) 9 Modern Music (1781) William Billings 10 O look to Golgotha (1843) Lowell Mason (1792–1872) 11 Amazing Grace (1847) [2, 5] arr. William Walker (1809–1875) intermission 12 Flow gently, sweet Afton (1857) J. E. Spilman (1812–1896) arr. J. S. Warren 13 Come where my love lies dreaming (1855) Stephen Foster (1826–1864) 14 Hymn of Peace (1869) O. W. Holmes (1809–1894)/ Matthias Keller (1813–1875) 15 Minuet (1903) Patty Stair (1868–1926) 16 Through the house give glimmering light (1897) Amy Beach (1867–1944) 17 So sweet is she (1916) Patty Stair 18 The Witch (1898) Edward MacDowell (1860–1908) writing as Edgar Thorn 19 Don’t be weary, traveler (1920) [6] R. -

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

Naming a Chord Once You Know the Common Names of the Intervals, the Naming of Chords Is a Little Less Daunting

Naming a Chord Once you know the common names of the intervals, the naming of chords is a little less daunting. Still, there are a few conventions and short-hand terms that many musicians use, that may be confusing at times. A few terms are used throughout the maze of chord names, and it is good to know what they refer to: Major / Minor – a “minor” note is one half step below the “major.” When naming intervals, all but the “perfect” intervals (1,4, 5, 8) are either major or minor. Generally if neither word is used, major is assumed, unless the situation is obvious. However, when used in naming extended chords, the word “minor” usually is reserved to indicate that the third of the triad is flatted. The word “major” is reserved to designate the major seventh interval as opposed to the minor or dominant seventh. It is assumed that the third is major, unless the word “minor” is said, right after the letter name of the chord. Similarly, in a seventh chord, the seventh interval is assumed to be a minor seventh (aka “dominant seventh), unless the word “major” comes right before the word “seventh.” Thus a common “C7” would mean a C major triad with a dominant seventh (CEGBb) While a “Cmaj7” (or CM7) would mean a C major triad with the major seventh interval added (CEGB), And a “Cmin7” (or Cm7) would mean a C minor triad with a dominant seventh interval added (CEbGBb) The dissonant “Cm(M7)” – “C minor major seventh” is fairly uncommon outside of modern jazz: it would mean a C minor triad with the major seventh interval added (CEbGB) Suspended – To suspend a note would mean to raise it up a half step. -

MTO 0.7: Alphonce, Dissonance and Schumann's Reckless Counterpoint

Volume 0, Number 7, March 1994 Copyright © 1994 Society for Music Theory Bo H. Alphonce KEYWORDS: Schumann, piano music, counterpoint, dissonance, rhythmic shift ABSTRACT: Work in progress about linearity in early romantic music. The essay discusses non-traditional dissonance treatment in some contrapuntal passages from Schumann’s Kreisleriana, opus 16, and his Grande Sonate F minor, opus 14, in particular some that involve a wedge-shaped linear motion or a rhythmic shift of one line relative to the harmonic progression. [1] The present paper is the first result of a planned project on linearity and other features of person- and period-style in early romantic music.(1) It is limited to Schumann's piano music from the eighteen-thirties and refers to score excerpts drawn exclusively from opus 14 and 16, the Grande Sonate in F minor and the Kreisleriana—the Finale of the former and the first two pieces of the latter. It deals with dissonance in foreground terms only and without reference to expressive connotations. Also, Eusebius, Florestan, E.T.A. Hoffmann, and Herr Kapellmeister Kreisler are kept gently off stage. [2] Schumann favours friction dissonances, especially the minor ninth and the major seventh, and he likes them raw: with little preparation and scant resolution. The sforzato clash of C and D in measures 131 and 261 of the Finale of the G minor Sonata, opus 22, offers a brilliant example, a peculiarly compressed dominant arrival just before the return of the main theme in G minor. The minor ninth often occurs exposed at the beginning of a phrase as in the second piece of the Davidsbuendler, opus 6: the opening chord is a V with an appoggiatura 6; as 6 goes to 5, the minor ninth enters together with the fundamental in, respectively, high and low peak registers. -

A Group-Theoretical Classification of Three-Tone and Four-Tone Harmonic Chords3

A GROUP-THEORETICAL CLASSIFICATION OF THREE-TONE AND FOUR-TONE HARMONIC CHORDS JASON K.C. POLAK Abstract. We classify three-tone and four-tone chords based on subgroups of the symmetric group acting on chords contained within a twelve-tone scale. The actions are inversion, major- minor duality, and augmented-diminished duality. These actions correspond to elements of symmetric groups, and also correspond directly to intuitive concepts in the harmony theory of music. We produce a graph of how these actions relate different seventh chords that suggests a concept of distance in the theory of harmony. Contents 1. Introduction 1 Acknowledgements 2 2. Three-tone harmonic chords 2 3. Four-tone harmonic chords 4 4. The chord graph 6 References 8 References 8 1. Introduction Early on in music theory we learn of the harmonic triads: major, minor, augmented, and diminished. Later on we find out about four-note chords such as seventh chords. We wish to describe a classification of these types of chords using the action of the finite symmetric groups. We represent notes by a number in the set Z/12 = {0, 1, 2,..., 10, 11}. Under this scheme, for example, 0 represents C, 1 represents C♯, 2 represents D, and so on. We consider only pitch classes modulo the octave. arXiv:2007.03134v1 [math.GR] 6 Jul 2020 We describe the sounding of simultaneous notes by an ordered increasing list of integers in Z/12 surrounded by parentheses. For example, a major second interval M2 would be repre- sented by (0, 2), and a major chord would be represented by (0, 4, 7). -

⁄Sþç}˛Ðn‚9Ô£ Rð˘¯Þ

559191 bk BEACH EU 25/05/2004 04:34pm Page 16 To her whose voice and loving hands fl Though I take the wings of morning, Op. 152 Can soothe our heart’s unrest, (1941) MERICAN LASSICS We bring these flowers, fragrant, fair, Though I take the wings of morning A C Our life her love hath blest! To the utmost sea, MAY FLOWERS Lyrics by Ana Mulford Addison Moody Yet my soul hath no sojourning Music by Amy Beach g1933 A.P. SCHMIDT CO. To outdistance Thee. Copyright Renewed and Assigned to SUMMY-BIRCHARD AMY BEACH MUSIC, a division of SUMMY-BIRCHARD INC. Though I climb to highest heaven, All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission of Warner Bros. ’Tis Thy dwelling high; Publications U.S. Inc. Though to death’s dark chamber given, Thou art standing by. fi I sought the Lord, Op. 142 (1937) Songs I sought the Lord, and afterward I knew If I say, the darkness hides me, He moved my soul to seek Him, seeking me; Turns my night to day; It was not I that found, O Saviour true; For with Thee no dark can find me, No, I was found of Thee. Shadows must away! The Year’s at the Spring Thou didst reach forth Thy hand and mine enfold; Even so, Thy hand shall lead me, I Sought the Lord I walked and sank not on the stormy sea; Flee Thee as I will; ’Twas not so much that I on Thee took hold, And Thy strong right arm shall hold me: As Thou, dear Lord, on me. -

The John and Anna Gillespie Papers an Inventory of Holdings at the American Music Research Center

The John and Anna Gillespie papers An inventory of holdings at the American Music Research Center American Music Research Center, University of Colorado at Boulder The John and Anna Gillespie papers Descriptive summary ID COU-AMRC-37 Title John and Anna Gillespie papers Date(s) Creator(s) Repository The American Music Research Center University of Colorado at Boulder 288 UCB Boulder, CO 80309 Location Housed in the American Music Research Center Physical Description 48 linear feet Scope and Contents Papers of John E. "Jack" Gillespie (1921—2003), Professor of music, University of California at Santa Barbara, author, musicologist and organist, including more than five thousand pieces of photocopied sheet music collected by Dr. Gillespie and his wife Anna Gillespie, used for researching their Bibliography of Nineteenth Century American Piano Music. Administrative Information Arrangement Sheet music arranged alphabetically by composer and then by title Access Open Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the American Music Research Center. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], John and Anna Gillespie papers, University of Colorado, Boulder Index Terms Access points related to this collection: Corporate names American Music Research Center - Page 2 - The John and Anna Gillespie papers Detailed Description Bibliography of Nineteenth-Century American Piano Music Music for Solo Piano Box Folder 1 1 Alden-Ambrose 1 2 Anderson-Ayers 1 3 Baerman-Barnes 2 1 Homer N. Bartlett 2 2 Homer N. Bartlett 2 3 W.K. Bassford 2 4 H.H. Amy Beach 3 1 John Beach-Arthur Bergh 3 2 Blind Tom 3 3 Arthur Bird-Henry R. -

June 1902) Winton J

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 6-1-1902 Volume 20, Number 06 (June 1902) Winton J. Baltzell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Baltzell, Winton J.. "Volume 20, Number 06 (June 1902)." , (1902). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/471 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PUBLISHER OF THE ETVDE WILL SUPPLY ANYTHING IN MUSIC. 11^ VPl\W4-»* _ The Sw»d Volume ol ••The Cmet In Mmk" mil be rmdy to «'»!' >* Apnl "* WORK m VOLUME .. 5KI55 nETUDE I, Clic.pl". Oodard. and Sohytte. II. Chamlnade. J^ ^ Sthumann and Mosz- Q. Smith. A. M. Foerater. and Oeo. W. W|enin«ki. VI. kowski (Schumann occupies 75 pages). • Kelley» Wm. Berger, and Deahm. and Fd. Sehnett. VII. It. W. O. B. Klein. VIII, Saint-Saens, Paderewski, Q Y Bn|ch Max yogrich. IX. (llazounov, Balakirev, the Waltz Strau ’ M g Forces in the X. Review ol the Coum a. a Wholes The Place ol Bach nr Development; Influence ol the Folks Song, etc. -

Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteenth Chords Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteen Chords Sometimes Referred to As Chords with 'Extensions', I.E

Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteenth chords Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteen chords sometimes referred to as chords with 'extensions', i.e. extending the seventh chord to include tones that are stacking the interval of a third above the basic chord tones. These chords with upper extensions occur mostly on the V chord. The ninth chord is sometimes viewed as superimposing the vii7 chord on top of the V7 chord. The combination of the two chord creates a ninth chord. In major keys the ninth of the dominant ninth chord is a whole step above the root (plus octaves) w w w w w & c w w w C major: V7 vii7 V9 G7 Bm7b5 G9 ? c ∑ ∑ ∑ In the minor keys the ninth of the dominant ninth chord is a half step above the root (plus octaves). In chord symbols it is referred to as a b9, i.e. E7b9. The 'flat' terminology is use to indicate that the ninth is lowered compared to the major key version of the dominant ninth chord. Note that in many keys, the ninth is not literally a flatted note but might be a natural. 4 w w w & #w #w #w A minor: V7 vii7 V9 E7 G#dim7 E7b9 ? ∑ ∑ ∑ The dominant ninth usually resolves to I and the ninth often resolves down in parallel motion with the seventh of the chord. 7 ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ & ˙ ˙ #˙ ˙ C major: V9 I A minor: V9 i G9 C E7b9 Am ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ? ˙ ˙ The dominant ninth chord is often used in a II-V-I chord progression where the II chord˙ and the I chord are both seventh chords and the V chord is a incomplete ninth with the fifth omitted. -

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Claire Arthur, B.Mus., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: David Huron, Advisor David Clampitt Anna Gawboy c Copyright by Claire Arthur 2016 Abstract An empirical investigation is made of musical qualia in context. Specifically, scale-degree qualia are evaluated in relation to a local harmonic context, and rhythm qualia are evaluated in relation to a metrical context. After reviewing some of the philosophical background on qualia, and briefly reviewing some theories of musical qualia, three studies are presented. The first builds on Huron's (2006) theory of statistical or implicit learning and melodic probability as significant contributors to musical qualia. Prior statistical models of melodic expectation have focused on the distribution of pitches in melodies, or on their first-order likelihoods as predictors of melodic continuation. Since most Western music is non-monophonic, this first study investigates whether melodic probabilities are altered when the underlying harmonic accompaniment is taken into consideration. This project was carried out by building and analyzing a corpus of classical music containing harmonic analyses. Analysis of the data found that harmony was a significant predictor of scale-degree continuation. In addition, two experiments were carried out to test the perceptual effects of context on musical qualia. In the first experiment participants rated the perceived qualia of individual scale-degrees following various common four-chord progressions that each ended with a different harmony. -

Musicianship IV Syllabus

University of Missouri-Kansas City Conservatory of Music and Dance CONS 242: Musicianship IV Spring 2015 Credit hours: 4.0 CRN: 17576 Instructor: Dr. David Thurmaier, Associate Professor of Music Theory Office: 302 Grant Hall Phone: 235-2898 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: M, T, W from 10-10:50 and by appointment Teaching Assistant: Taylor Carmona Office: 304 Grant Hall Email: [email protected] Catalog Description Continuation of CONS 241. Study of late-nineteenth century chromaticism and analytical and compositional methods of twentieth and twenty-first century music, including set theory and twelve-tone theory. Particular attention is given to the development of critical writing skills and the creation of stylistic compositions. Prerequisite: CONS 241 Meeting Time and Location Monday-Friday, 9-9:50 am, Grant Hall 122 Required Materials Kostka, Stefan and Roger Graybill. Anthology of Music for Analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2004. Laitz, Steven G., The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Tonal Theory, Analysis, and Listening. 3rd Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. Roig-Francolí, Miguel. Understanding Post-Tonal Music (text and anthology). Boston: McGraw Hill, 2007. Notebook, music paper and pens/pencils In addition, you will be required to use the Finale notation program (or equivalent) for composition assignments. This is available for personal purchase at a substantial student discount http://www.finalemusic.com. I recommend against using such free programs as Notepad, as you are not able to take advantage of the many features of Finale. Continual failure to purchase and/or bring required books will result in deductions on homework or exams. -

Johann Strauss Emperor Waltz - Kaiserwalzer Mp3, Flac, Wma

Johann Strauss Emperor Waltz - Kaiserwalzer mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Emperor Waltz - Kaiserwalzer Country: Brazil Released: 1973 Style: Romantic MP3 version RAR size: 1938 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1722 mb WMA version RAR size: 1690 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 651 Other Formats: XM ADX RA VOC MP4 MP3 APE Tracklist A1 –Johann Strauss* An Der Schönen Blauen Donau, Op. 314 A2 –Johann Strauss* Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka, Op. 214 A3 –Johann Strauss* Kaiser-Walzer, Op. 437 B1 –Johann Strauss* Unter Donner Und Blitz, Op. 324 B2 –Johann Strauss* Rosen Aus Dem Süden, Op. 388 B3 –Josef Strauss*, Johann Strauss* Pizzicato-Polka B4 –Johann Strauss* Annen-Polka, Op. 117 B5 –Johann Strauss* Perpetuum Mobile, Op. 257 Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Companhia Brasileira De Discos Phonogram Distributed By – Companhia Brasileira De Discos Phonogram Credits Conductor – Karl Böhm Orchestra – Wiener Philharmoniker Notes Vinyl has the generic yellow Company labels with top small Tulips motif logo and straight borders. Vinyl is held in a fully laminated picture cover which has 'Serie De Luxo' back top print. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Johann Strauss* & Johann Strauss* & Josef Strauss* - Deutsche 2530 316 2530 316 Germany 1973 Josef Strauss* Emperor Waltz - Grammophon Kaiserwalzer (LP) Johann Strauss* & DK 214 Johann Strauss* & Josef Strauss* - Deutsche DK 214 US 1978 LPS Josef Strauss* Emperor Waltz - Klassische LPS Kaiserwalzer (LP) Johann* Et Joseph Johann* Et Joseph Strauss* /