Guns, Planes and Ships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Change 3, FAA Order 7340.2A Contractions

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION 7340.2A CHG 3 SUBJ: CONTRACTIONS 1. PURPOSE. This change transmits revised pages to Order JO 7340.2A, Contractions. 2. DISTRIBUTION. This change is distributed to select offices in Washington and regional headquarters, the William J. Hughes Technical Center, and the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center; to all air traffic field offices and field facilities; to all airway facilities field offices; to all international aviation field offices, airport district offices, and flight standards district offices; and to the interested aviation public. 3. EFFECTIVE DATE. July 29, 2010. 4. EXPLANATION OF CHANGES. Changes, additions, and modifications (CAM) are listed in the CAM section of this change. Changes within sections are indicated by a vertical bar. 5. DISPOSITION OF TRANSMITTAL. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. PAGE CONTROL CHART. See the page control chart attachment. Y[fa\.Uj-Koef p^/2, Nancy B. Kalinowski Vice President, System Operations Services Air Traffic Organization Date: k/^///V/<+///0 Distribution: ZAT-734, ZAT-464 Initiated by: AJR-0 Vice President, System Operations Services 7/29/10 JO 7340.2A CHG 3 PAGE CONTROL CHART REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−2 . 4/8/10 CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−2 . 7/29/10 1−1−1 . 8/27/09 1−1−1 . 7/29/10 2−1−23 through 2−1−27 . 4/8/10 2−1−23 through 2−1−27 . 7/29/10 2−2−28 . 4/8/10 2−2−28 . 4/8/10 2−2−23 . -

The Impact of European Union Air Safety Bans

SIPRI Insights on Peace and Security No. 2008/3 October 2008 STEMMING DESTABILIZING SUMMARY w This paper examines the ARMS TRANSFERS: impact of EU air safety regula- tions on the activities of air THE IMPACT OF EUROPEAN cargo operators that are sus- pected of being involved in destabilizing arms transfers. UNION AIR SAFETY BANS Air safety regulations are an underutilized but potentially hugh griffiths and mark bromley promising tool for stemming the flow of destabilizing arms I. Introduction transfers. Air cargo operators involved in destabilizing arms transfers habitually violate air Numerous organizations and bodies, including the Organisation for Security safety standards, increasing and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the Wassenaar Arrangement, and the the likelihood of their being European Union (EU) have identified the central role played by air cargo targeted by EU controls. Of the operators in destabilizing arms transfers,2 particularly of small arms and 172 air cargo carriers that have light weapons (SALW).3 Such transfers have proved especially detrimental been listed in EC air safety reg- in Africa, where they have helped to fuel the continent’s various conflicts ulations, barring them from and threatened fragile states and societies. Most air cargo carriers involved entering EU airspace, or tar- geted as a result of EU technical in destabilizing arms transfers, including those accused of violating interna- inspection missions, 80 have tional United Nations arms embargoes, have remained largely free of effec- been named in United Nations tive restriction or sanctions prior to 2006 and no air cargo operator has been Security Council or other arms convicted in court for transporting small arms to an embargoed destina- trafficking-related reports. -

Air Transport and Destabilizing Commodity Flows, SIPRI Policy

SIPRI Policy Paper AIR TRANSPORT AND 24 DESTABILIZING May 2009 COMMODITY FLOWS hugh griffiths and mark bromley STOCKHOLM INTERNATIONAL PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE SIPRI is an independent international institute for research into problems of peace and conflict, especially those of arms control and disarmament. It was established in 1966 to commemorate Sweden’s 150 years of unbroken peace. The Institute is financed mainly by a grant proposed by the Swedish Government and subsequently approved by the Swedish Parliament. The staff and the Governing Board are international. The Institute also has an Advisory Committee as an international consultative body. The Governing Board is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. GOVERNING BOARD Ambassador Rolf Ekéus, Chairman (Sweden) Dr Willem F. van Eekelen, Vice-Chairman (Netherlands) Dr Alexei G. Arbatov (Russia) Jayantha Dhanapala (Sri Lanka) Dr Nabil Elaraby (Egypt) Professor Mary Kaldor (United Kingdom) Professor Ronald G. Sutherland (Canada) The Director DIRECTOR Dr Bates Gill (United States) Signalistgatan 9 SE-169 70 Solna, Sweden Telephone: +46 8 655 97 00 Fax: +46 8 655 97 33 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.sipri.org Air Transport and Destabilizing Commodity Flows SIPRI Policy Paper No. 24 HUGH GRIFFITHS AND MARK BROMLEY STOCKHOLM INTERNATIONAL PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE May 2009 © SIPRI 2009 Corrected version January 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of SIPRI or as expressly permitted by law. Printed in Sweden by Elanders ISSN 1652–0432 (print) ISSN 1653–7548 (online) ISBN 978–91–85114–60–3 Contents Preface v Summary vi Abbreviations viii 1. -

Airliner Census Western-Built Jet and Turboprop Airliners

World airliner census Western-built jet and turboprop airliners AEROSPATIALE (NORD) 262 7 Lufthansa (600R) 2 Biman Bangladesh Airlines (300) 4 Tarom (300) 2 Africa 3 MNG Airlines (B4) 2 China Eastern Airlines (200) 3 Turkish Airlines (THY) (200) 1 Equatorial Int’l Airlines (A) 1 MNG Airlines (B4 Freighter) 5 Emirates (300) 1 Turkish Airlines (THY) (300) 5 Int’l Trans Air Business (A) 1 MNG Airlines (F4) 3 Emirates (300F) 3 Turkish Airlines (THY) (300F) 1 Trans Service Airlift (B) 1 Monarch Airlines (600R) 4 Iran Air (200) 6 Uzbekistan Airways (300) 3 North/South America 4 Olympic Airlines (600R) 1 Iran Air (300) 2 White (300) 1 Aerolineas Sosa (A) 3 Onur Air (600R) 6 Iraqi Airways (300) (5) North/South America 81 RACSA (A) 1 Onur Air (B2) 1 Jordan Aviation (200) 1 Aerolineas Argentinas (300) 2 AEROSPATIALE (SUD) CARAVELLE 2 Onur Air (B4) 5 Jordan Aviation (300) 1 Air Transat (300) 11 Europe 2 Pan Air (B4 Freighter) 2 Kuwait Airways (300) 4 FedEx Express (200F) 49 WaltAir (10B) 1 Saga Airlines (B2) 1 Mahan Air (300) 2 FedEx Express (300) 7 WaltAir (11R) 1 TNT Airways (B4 Freighter) 4 Miat Mongolian Airlines (300) 1 FedEx Express (300F) 12 AIRBUS A300 408 (8) North/South America 166 (7) Pakistan Int’l Airlines (300) 12 AIRBUS A318-100 30 (48) Africa 14 Aero Union (B4 Freighter) 4 Royal Jordanian (300) 4 Europe 13 (9) Egyptair (600R) 1 American Airlines (600R) 34 Royal Jordanian (300F) 2 Air France 13 (5) Egyptair (600R Freighter) 1 ASTAR Air Cargo (B4 Freighter) 6 Yemenia (300) 4 Tarom (4) Egyptair (B4 Freighter) 2 Express.net Airlines -

The Impact of European Union Air Safety Bans

SIPRI Insights on Peace and Security No. 2008/3 October 2008 STEMMING DESTABILIZING SUMMARY w This paper examines the ARMS TRANSFERS: THE impact of EU air safety regulations on the activities of IMPACT OF EUROPEAN UNION air cargo operators that are suspected of being involved in destabilizing arms transfers. AIR SAFETY BANS Air safety regulations are an underutilized but potentially hugh griffiths and mark bromley promising tool for stemming the flow of destabilizing arms I. Introduction transfers. Air cargo operators involved in destabilizing arms transfers habitually violate air Numerous organizations and bodies, including the Organisation for Security safety standards, increasing the and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the Wassenaar Arrangement, and the likelihood of their being European Union (EU) have identified the central role played by air cargo targeted by EU controls. operators in destabilizing arms transfers,2 particularly of small arms and Of the 172 air cargo carriers light weapons (SALW).3 Such transfers have proved especially detrimental that have been listed in EC air in Africa, where they have helped to fuel the continent’s various conflicts safety regulations, barring and threatened fragile states and societies. Most air cargo carriers involved them from entering EU airspace, or targeted as a result in destabilizing arms transfers, including those accused of violating interna- of EU technical inspection tional United Nations arms embargoes, have remained largely free of effec- missions, 80 have been named tive restriction or sanctions prior to 2006 and no air cargo operator has been in United Nations Security convicted in court for transporting small arms to an embargoed destina- Council or other arms 6 tion. -

Air Transport and Destabilizing Commodity Flows 24 DESTABILIZING May 2009

STOCKHOLM INTERNATIONAL PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE SIPRI Policy Paper AIR TRANSPORT AND Air Transport and Destabilizing Commodity Flows 24 DESTABILIZING May 2009 Destabilizing and illicit flows of small arms and light weapons, cocaine, COMMODITY FLOWS tobacco and valuable raw materials fuel the war economies that have devastated much of Africa in recent decades. This Policy Paper hugh griffiths and mark bromley unequivocally establishes the role of air transport across the full spectrum of these commodity flows. It also demonstrates the extent to which air transport actors named in United Nations and other arms trafficking- related reports have become enmeshed in humanitarian aid, peace support, stability operations and defence logistics supply chains. This pioneering analysis provides a range of policy options available to the European Union (EU) for improving mechanisms for monitoring and controlling these air transport actors. It shows that existing EU tools and empirically proven programmes can be adapted and applied with minimal cost and effort to address some of the most pressing security threats facing the world today. Hugh Griffiths (United Kingdom) is a Researcher with the Countering Illicit Trafficking–Mechanism Assessment Project (CIT-MAP) of the SIPRI Arms Transfers Programme. From 1995 until 2007 he worked for governments, the UN and non-governmental organizations in Eastern Europe and the Balkans, conducting investigative field research, analysis and programme management on issues surrounding humanitarian aid, clandestine political economies, conflict, and small arms and light weapons. Mark Bromley (United Kingdom) is a Researcher with the SIPRI Arms Transfers Programme. Previously, he was a Policy Analyst for the British American Security Information Council (BASIC). -

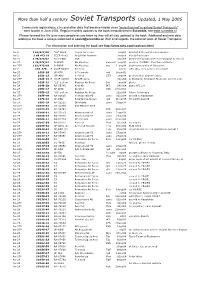

Than Half a Century Soviet Transports Updated, 1 May 2005

More than half a century Soviet Transports Updated, 1 May 2005 Covers new registrations, c/ns and other data that became known since "more than half a century Soviet Transports" went to print in June 2004. Regular monthly updates to the book are published in Scramble, see www.scramble.nl Please forward this file to as many people as you know so they will all stay updated to the book. Additional and new data adding to the book is always welcomed at [email protected]. With kind regards, the editorial team of Soviet Transports For information and ordering the book see http://www.tahs.com/sovtrans.html An-2 1 60(473)06 "40" black Soviet Air Force may04 derelict & stored at Kiev museum An-2 1 64 473 10 CCCP-N542 AFL/Polar Aviation ..may58 dbr by hurricane An-2T 1 78(473)07 ex D-FONI FSB 25jul04 preserved by gas station at Wolgast in red c/s An-2T 1 78(473)12 D-FKMD Air Albatros Kamenz mar05 marked 'D-FONE', Red Baron tribute An-2TP 1 81(473)18 D-FONE Air Albatros w/o 21aug04 destroyed by fire at Dinslaken An-2 113. 473 .. ? CCCP-04352 Aeroflot photo with skis, only part of c/n visible An-2T 1G15-28 SP-KTK S.Tolwinski rgd 14aug02 An-2T 1G26-13 'SP-ANL' no titles STR ..mar04 preserved at airport terrace An-2TP 1G28-01 ? CCCP-44998 AFL/Moscow 04jul04 at Budapest Transport Museum; c/n not conf. An-2T 1G28-21 "12" yellow Russian Air Force Ivk ..aug04 photo An-2R 1G49-38 RA-55745 Kras Air IKT 04jul04 basic AFL c/s An-2T 1G52-17 SP-AMO Kreistel PZN 27mar04 An-2T 1G59-23 "02" yellow Russian Air Force 21jun04 Pskov-Polkovaya An-2TP 1G75-09 RA-09625 -

Arms Transportation, Brokering and the Threat to Human Rights

Table of Contents TABLE OF BOXES AND MAPS ...........................................................................................................1 DEFINITIONS .........................................................................................................................................2 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................3 FACING THE SQUEEZE - EXPORT SOUTH .................................................................................................. 5 STATES FAILING TO ADDRESS THE CHAIN ............................................................................................... 7 2. THE PROBLEM OF DELIVERY – SOME ILLUSTRATIONS ..................................................11 CHINESE AND US ARMS TO NEPAL – BY TRUCK AND BY AIR................................................................ 11 BROKERING LOGISTICS FOR US CLANDESTINE OPERATIONS ................................................................ 14 ARMS BROKERS AND TRAFFICKING TO THE COLOMBIAN PARAMILITARIES .......................................... 16 THE KARIN CAT – HELPING PREPARE A MAJOR INVASION .................................................................... 18 ARMS FROM BRAZIL SEIZED IN SOUTH AFRICA ................................................................................... 20 INTERNATIONAL SHIPPING NETWORK FOR ARMS FROM CHINA TO LIBERIA ......................................... 22 3. ORGANIZING MILITARY SUPPLY CHAINS AND ARMS -

Ecacnews No 29Final

ECAC news TThehe EEuropeanuropean CCivilivil AAviationviation CConferenceonference MagazineMagazine e l i v i c s n o i t a i v o A ’ l e f d e n n e n é p o r i u e e c n e r é f C n o C a l e A d e n i z E a g FOCUS ON ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION a m GROS PLAN SUR LES ENQUÊTES ACCIDENTS e C Le magazine de la Conférence européenne de l’Aviation civile de l’Aviation LLe magazine de la Conférence européenne ECAC news is published by the European Civil Aviation Conference (ECAC) CIVIL AVIATION IN CEAC infos est publié par la Conférence européenne de l’Aviation civile (CEAC) SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO For further information, please contact: L’AVIATION CIVILE EN SERBIE-MONTÉNÉGRO Pour plus d’informations, veuillez contacter : Angelika Kupka 5 - 20 Tel./Tél : +33 (0)1 46 41 85 09 5 0 e-mail/courriel : [email protected] 9 5 3 bis, Villa Emile Bergerat 1 92522 Neuilly/Seine Cedex FRANCE Tel./Tél : +33 (0)1 46 41 85 44 Fax : +33 (0)1 46 24 18 18 Number 29 — Winter 2004/2005 e-mail/courriel : [email protected] numéro 29— hiver 2004/2005 Internet : www.ecac-ceac.org Printed in Levallois by IMPRIMSET Imprimé à Levallois par IMPRIMSET CONTENTS CEAC EN BREF SOMMAIRE NOUVELLES DES ÉTATS MEMBRES Le Point focal pour les questions économiques, M. Krzysztof 1 EDITORIAL BY JOHN LUMSDEN, IRELAND ÉDITORIAL PAR JOHN LUMSDEN, IRLANDE 1 Kapis, Directeur général de l’Aviation civile de Pologne, a rendu Les nouveaux Directeurs généraux de l’Aviation civile suivants compte des travaux en cours à ce stade concernant la propriété 2 THE GROUP OF EXPERTS ON ACCIDENT LE GROUPE D’EXPERTS DES ENQUÊTES SUR LES ACCIDENTS - 2 ont pris leurs fonctions : en Albanie, M. -

FAAO JO 7340.2 CHG 3 Package

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION JO 7340.2 CHG 3 SUBJ: CONTRACTIONS 1. PURPOSE. This change transmits revised pages to Order JO 7340.2, Contractions. 2. DISTRIBUTION. This change is distributed to select offices in Washington and regional headquarters, the William J. Hughes Technical Center, and the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center; to all air traffic field offices and field facilities; to all airway facilities field offices; to all intemational aviation field offices, airport district offices, and flight standards district offices; and to interested aviation public. 3. EFFECTIVE DATE. May 7, 2009. 4. EXPLANATION OF CHANGES. Cancellations, additions, and modifications (CAM) are listed in the CAM section of this change. Changes within sections are indicated by a vertical bar. 5. DISPOSITION OF TRANSMITTAL. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. PAGE CONTROL CHART. See the page control chart attachment. tf ,<*. ^^^Nancy B. Kalinowski Vice President, System Operations Services Air Traffic Organization Date: y-/-<3? Distribution: ZAT-734, ZAT-4S4 Initiated by: AJR-0 Vice President, System Operations Services 5/7/09 JO 7340.2 CHG 3 PAGE CONTROL CHART REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−3 . 1/15/09 CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−3 . 5/7/09 1−1−1 . 6/5/08 1−1−1 . 5/7/09 3−1−15 . 6/5/08 3−1−15 . 6/5/08 3−1−16 . 6/5/08 3−1−16 . 5/7/09 3−1−19 . 6/5/08 3−1−19 . 6/5/08 3−1−20 . -

Integration of Nuclear Spectrometry Methods As a New Approach to Material Research

Integration of Material Research as a Approach New to Nuclear Spectrometry Methods IAEA-TECDOC-1669 spine 8,2 mm IAEA-TECDOC-1669 n INTEGRatioN OF NUCLEAR SPECTROMETRY METHODS AS A NEW APPROACH TO MATERIAL RESEARCH VIENNA ISSN 1011–4289 ISBN 978–92–0–121310–5 INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY ENERGY ATOMIC INTERNATIONAL Integration of Nuclear Spectrometry Methods as a New Approach to Material Research The following States are Members of the International Atomic Energy Agency: AFGHANISTAN GHANA NORWAY ALBANIA GREECE OMAN ALGERIA GUATEMALA PAKISTAN ANGOLA HAITI PALAU ARGENTINA HOLY SEE PANAMA ARMENIA HONDURAS PARAGUAY AUSTRALIA HUNGARY PERU AUSTRIA ICELAND PHILIPPINES AZERBAIJAN INDIA POLAND BAHRAIN INDONESIA PORTUGAL BANGLADESH IRAN, ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF QATAR BELARUS IRAQ REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA BELGIUM IRELAND ROMANIA BELIZE ISRAEL RUSSIAN FEDERATION BENIN ITALY SAUDI ARABIA BOLIVIA JAMAICA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA JAPAN SENEGAL BOTSWANA JORDAN SERBIA BRAZIL KAZAKHSTAN SEYCHELLES BULGARIA KENYA SIERRA LEONE BURKINA FASO KOREA, REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE BURUNDI KUWAIT SLOVAKIA CAMBODIA KYRGYZSTAN SLOVENIA CAMEROON LATVIA SOUTH AFRICA CANADA LEBANON SPAIN CENTRAL AFRICAN LESOTHO SRI LANKA REPUBLIC LIBERIA SUDAN CHAD LIBYA SWEDEN CHILE LIECHTENSTEIN SWITZERLAND CHINA LITHUANIA SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC COLOMBIA LUXEMBOURG TAJIKISTAN CONGO MADAGASCAR THAILAND COSTA RICA MALAWI THE FORMER YUGOSLAV CÔTE DIVOIRE MALAYSIA REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA CROATIA MALI TUNISIA CUBA MALTA TURKEY CYPRUS MARSHALL ISLANDS UGANDA CZECH REPUBLIC MAURITANIA UKRAINE DEMOCRATIC