Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

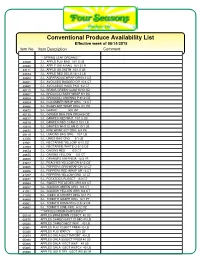

Conventional Produce Availability List

$PLPRESS=FCPRT01; 06/11/15 Four Seasons Produce Co. PAGE Phone #: 800-422-8384 Fax #: (717) 721-2597 PRICE LIST P92017Conventional FOUR SEASONS PRODUCE Produce INC Availability Attention: List 06/11/15 to 06/12/15 Effective week of 06/14/2015 Item#Item No.Item DescriptionItem Description Price Comment Comment ===== ============================== ======= ============================== ***SPRING LEAF ORGANIC*** 43306 ***SPRINGS.L. APPLELEAF FUJIORGANIC*** BAG 18/1.5 LB 4330642940 S.L. APPLES.L. APPLE FUJI GALA BAG BAG 18/1.5 18/1.5 LBLB 58.00 4294043111 S.L. APPLES.L. APPLE GALA GR BAG SMITH 18/1.5 18/1.5 LBLB 58.00 4311143074 S.L. APPLES.L. APPLE GR SMITH RED DEL 18/1.5 B 18/1.5 LBLB 69.00 4307449663 S.L. APPLES.L. ASPARAGUS RED DEL BWRAP 18/1.5 OR 6/12 LB OZ 39.50 4966346801 S.L. ASPARAGUSS.L. AVOCADO WRAP BAGGED OR 6/12 OR 15/4 OZ CT 29.50 4680149665 S.L. AVOCADOS.L. AVOCADOS BAGGED HASS OR PKG15/4 6/2 CT CT 54.00 4966548110 S.L. AVOCADOSS.L. BEANS HASS GREEN PKG CLAM 6/2 10/12 CT OZ 22.50 4811049667 S.L. BEANSS.L. BROCCOLI GREEN CLAM BABY WRAP10/12 6/1 OZ BU 24.75 4966749659 S.L. BROCCOLIS.L. BROCCOLI BABY CROWNS WRAP 6/1 P 6/12 BU OZ 16.75 4965949654 S.L. BROCCOLIS.L. CUCUMBER CROWNS WRAP P 6/12ORG 12OZ CT 19.50 4965449666 S.L. CUCUMBERS.L. EGGPLANT WRAP WRAP ORG ORG 12 6/1CT PK 30.50 4966649672 S.L. -

Gitty-Up's Gourmet Goodies

Gitty-Up’s Gourmet Goodies (307) 214-7751 Order Form (307) 287-5421 SIZE PIES SIZE ♥SWEET BREADS SIZE ♥HONEY-w/Dipper $8 $15 *Spec ♥$7 ♥$11 Loaves ♥$3 ♥ $8 8” 10” 10”sf SM LG 4oz 10oz FLAVOR/TYPE ----- Old Fashioned Apple Banana Oatmeal ------ Honey- Amber-4oz ----- Apple Crumble Pumpkin ------ Honey- Dark-4oz ----- Cranberry-Cherry Zucchini Honey Sticks-.25¢ ea. ----- Seasonal Fruit Cranberry-Orange ♥ JELLY/ JAM ----- Honey Pumpkin Lemon-Blueberry ------ Caramel Apple ----- *Specialty Pies-$18 Almond Poppy Seed ------ Garden Grape ----- *Pecan Lemon Thyme ------ Peach Marmalade ----- Sour Cream Pies-$16 Irish Apple Cake »Limited Quantities ----- Rhubarb Carrot Cake ------ »Chokecherry-10oz ----- Sour Apple Coconut Cake ------ »Raspberry-10oz ----- Rhub-Berry Combos Loaded ------ »Crabapple-10oz Cheesecakes-$25 Options for Raisins/Nuts & or ------ »Spiced Plum-10oz *Spring -form Pan Bread/Muffins Chocolate chips ------ »Crabby Applesauce ---- ----- *Lemon $12 $24 ♥ MUFFINS ♥SYRUPS ---- ----- *Irish Cream 6pk Doz. ♥Single-$2.50 ea ------ Apple Pie Syrup-4oz ---- ----- *Pumpkin/WhtChoc Banana Oatmeal ♥Garden Salsa --- ---- *New York Style-$20 Pumpkin »ALL While Supplies Last NUMBER ♥COOKIES -3” Zucchini ♥3pk $4 ♥ BISCOTTI $6 $8 $15 ♥$1.50 ea Almond Poppy Seed ♥4pk 6pk Dz Lemon Thyme Cranberry-pistachio Ultimate Cowboy Pumpkin-Chocolate Vanilla-almond Chocolate Chip Chip Lemon-white choc. Bestest Oatmeal Lemon-Blueberry Cinnamon-sugar Peanut Butter PAN SIZE ♥SWEET ROLLS Chocolate Snicker doodles $20 $34 ♥ Single- $3 ea. SIZE BOUNTIFUL -

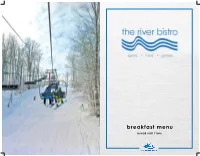

River-Bistro-Combine

breakfast menu served until 11am side dishes bacon, sausage or ham - 3.50 | hash browns - 2.50 cup of fruit - 5 | cold cereal - 4.25 toast or english muffin - 2.25 banana nut or blueberry muffin - 4.50 beverages breakfast coffee & tea - 3.25 | juice - 3.25 | coke products - 3.25 breakfast sandwich Scrambled eggs, bacon and American cheese on a toasted bagel. - 8 *Consuming raw or undercooked meats, poultry, seafood or fresh fruit plate eggs increases your risk of foodborne illness. Seasonal fruit with a side of yogurt. - 9.75 One guest check for parties of 10 or more with 19% gratuity added. River Bistro is not a gluten-free kitchen. bistro scrambler burrito Scrambled eggs with sausage, green pepper, onion, hash browns and cheddar cheese wrapped in a flour tortilla. - 10.75 cinnamon supreme french toast Luscious slices of cinnamon bread dipped in egg batter grilled to a golden brown and served with warm maple syrup. - 10.50 cedar river breakfast Two eggs, with bacon or sausage, served with hash browns, and toast or an English muffin. - 13.50 three egg omelette Three eggs with your choice of three of the following items: American, cheddar, Swiss or pepper jack cheese, bacon, ham, sausage, bell peppers, tomatoes, onions, mushrooms. Served with hash browns and toast or an English muffin. - 13.50 craft cocktails wine Red Snowball Martini Cabernet Vanilla vodka, blue curacao and Malibu coconut rum mixed with coconut cream, served in a glass with a shaved coconut rim. - 11 Pinot Noir Razzamatazz Cotes du Rhone Vodka and Chambord mixed with freshly muddled raspberry, lemon and lime, and Sprite, garnished with a raspberry and lemon. -

Disease and Insect Pests of Asparagus by William R

Page 1 Disease and insect pests of asparagus by William R. Morrison, III1, Sheila Linderman2, Mary K. Hausbeck2,3, Benjamin P. Werling3 and Zsofia Szendrei1,3 1MSU Department of Entomology; 2MSU Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences; and 3Michigan State University Extension Extension Bulletin E3219 Introduction Biology • Fungus. The goal of this bulletin is to provide basic information • Sexual stage of the fungus (Pleospora herbarum) produc- needed to identify, understand and control insect and es overwintering structures (pseudothecia), appearing as disease pests of asparagus. Because each pest is different, small, black dots on asparagus plant debris from previous control strategies are most effective when they are tai- season. lored to the species present in your production fields. For this reason, this bulletin includes sections on pest identifi- • Pseudothecia release ascospores via rain splash and cation that show key characteristics and pictures to help wind, causing the primary infection for the new season. you determine which pests are present in your asparagus. • Primary infection progresses in the asexual stage of the It is also necessary to understand pests and diseases in fungus (Stemphylium vesicarium), which produces multiple order to appropriately manage them. This bulletin includes spores (conidia) cycles throughout the growing season. sections on the biology of each major insect and disease • Conidia enter plant tissue through wounds and stoma- pest. Finally, it also provides information on cultural and ta, which are pores of a plant used for respiration. general pest control strategies. For specifics on the pesti- • Premature defoliation of the fern limits photosynthetic cides available for chemical control of each pest, consult capability of the plant, decreasing carbohydrate reserves in MSU Extension bulletin E312, “Insect, Disease, and Nema- tode Control for Commercial Vegetables” (Order in the the crown for the following year’s crop. -

Catering Menu

/ BREAK PACKAGES Minimum 10 people: Packages conclude after two hours of service FIESTA BREAK Mexican seven layer dip Southwest salsa & Mexican Queso Tortilla chips, peppers, sour cream THE EXECUTIVE Assorted soda $10.95/Guest MID MORNING BREAK Premium coffee, decaf, herbal teas and assorted soda ENERGY BREAK CHOICE OF TWO: Premium Coffee/Tea Service & Bottled water Gourmet brownies, Fresh sliced fruit tray Mini candy bars Fresh baked cookies Trail mix bar with assorted seasonal nuts Fresh fruit tray Assorted granola bars Fruit and cereal bars and granola bars $12.95/Guest Assorted energy bars Vegetable tray with dip THE SWEET N' SALTY BREAK ___________ Popcorn, Pretzels, Brownies AFTERNOON BREAK Assorted cookies Premium coffee, decaf, herbal teas and assorted soda Assorted soda, Coffee $10.95/Guest CHOICE OF TWO: Gourmet brownies THE PHILLY BREAK Mini candy bars Fresh baked cookies Premium coffee & tea service & assorted soda Fresh fruit tray Philadelphia's famous soft pretzels Fruit and cereal bars and granola bars Served with mustard & cheese Assorted energy bars Philadelphia's own Tastykake assorted pastry treats display Vegetable tray with dip $12.95/Guest $22.95/Guest MORNING BREAK Fresh Fruit Display CONTINUOUS BEVERAGE PACKAGE Assorted Danish & Muffins Served 6 Hours (No Modifications) Mini Quiches Assorted Soft Drinks & Bottled Water Make-Your-Own Parfait Station Freshly Brewed Coffee, Decaffeinated Coffee and Freshly Brewed Coffee, Decaf Coffee and Assorted Hot Tea Assorted Hot Tea $6.95/Guest $9.95/Guest BEVERAGES A LA CARTE -

Veggie Crunch Salad

Veggie Crunch Salad Kit Broccoli florets, diced cauliflower, celery, red onions, shredded carrots, bacon pieces, cranberries and cashews, finished with a cider Dijon dressing. Jake's Code: VK0002 Kit Components QTY Size Components 1 2.5 oz Bacon Pieces 2 4 oz Cranberry/Cashew Mix 1 18.4 oz Broccoli Florets 1 12.8 oz Match Stick Broccoli 1 4.8 oz Shredded Carrots 1 9.6 oz Diced Cauliflower 1 8 oz Diced Celery 1 8 oz Diced Red Onion 1 20 oz Dressing Ingredients: Broccoli, Dressing (Mayonnaise [Soybean Oil, Water, Salted Egg Yolks, Vinegar, Sugar, Salt, Mustard Flour], Sugar, Dijon Mustard [Water, Vinegar, Mustard Seed, White Wine, Fruit Pectin, Citric Acid, Tartaric Acid, Sugar, Spice], Apple Cider Vinegar, Celery Seed, Sodium Benzoate and Potassium Sorbate added to protect flavor, Garlic Powder), Cauliflower, Celery, Red Onion, Carrots, Dried Cranberries (Cranberries, Sugar, Sunflower Oil), Cashews (Cashews, Salt, Corn Syrup as tacking agent), Pork Bacon Pieces (Pork Cured with: Water, Salt, Sugar, Sodium Phosphates, Sodium Erythorbate, Sodium Nitrite. May Contain: Maple Flavor [Sugar, Maple Syrup, Corn Syrup, Maltodextrin, Natural and Artificial Flavors, Dextrose, Yeast Extract, Autolyzed Yeast Extract, Partially Hydrogenated Soybean Oil, Sunflower Oil, Propylene Glycol, Ethyl Alcohol, Polysorbate 80, Citric Acid], Maple Sugar). Allergens: Contains Egg, Tree Nuts (Cashews). Asian Noodle Salad Kit Asian noodles, shredded cabbage, baby corn, and green onion in a Asian sesame dressing topped with slivered almonds. Jake's Code: VK0003 Kit Components QTY Size Components 1 16 oz. Coleslaw Blend 1 1.5 oz. Green Onion 1 72 oz. Asian Noodle Salad 2 2 oz. -

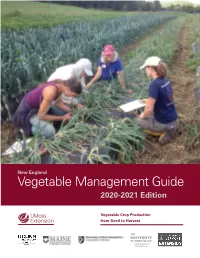

New England Vegetable Management Guide 2020-2021 Edition.Pdf

New England Vegetable Management Guide 2020-2021 Edition Vegetable Crop Production from Seed to Harvest COOPERATIVE EXTENSION Cover photo credit: Farmers and Extension Educators scout onions at High Meadows Farm in Westminster, VT. Photo by: Vern Grubinger, 2014. We would like to acknowledge the support received from the USDA Risk Management Agency to assist with the revision and publication of this document. 2020-2021 New England Vegetable Management Guide GENERAL EDITOR: Katie Campbell-Nelson SECTION EDITORS: Katherine Ghantous, Weeds Becky Sideman, Cultural Practices Cheryl Smith, Diseases Anna Wallingford, Insects PRODUCTION MANAGER: Lisa McKeag CONTRIBUTORS: University of Connecticut Shuresh Ghimire, Cultural Practices Leanne Pundt, Vegetable Transplants University of Maine James Dwyer, Cultural Practices David T. Handley, Cultural Practices Mark Hutton, Cultural Practices Alicyn Smart, Diseases University of Massachusetts Katie Campbell-Nelson, Cultural Practices Genevieve Higgins, Cultural Practices Angela Madeiras, Diseases Lisa McKeag, Cultural Practices Maggie Ng, Pest Management Susan Scheufele, Cultural Practices Tom Smiarowski, Risk Management University of New Hampshire Heather Bryant, Cultural Practices Jeremy Delisle, Cultural Practices Alan Eaton, Vertebrate Pest Management George Hamilton, Cultural Practices Olivia Saunders, Cultural Practices Becky Sideman, Cultural Practices University of Rhode Island Andy Radin, Cultural Practices University of Vermont Vern Grubinger, Cultural Practices Ann Hazelrigg, Diseases Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association Eric Sideman, Cultural Practices Caleb Goossen, Cultural Practices GRAPHIC DESIGN: Mickey Boisvert, MBDesign PAST CONTRIBUTORS: The following people have contributed to this publication over many years and this Guide reflects many of their contributions: Richard Ashley, A. Richard Bonnano, Ed Boutin, Jude Boucher, Kristen Castrataro, Pearly Colby, Douglas Cox, Jim Dill, Bess M. -

Produce Business August 2015

DOLE.indd 1 7/20/15 4:59 PM AUGUST 2015 • VOL. 31 • NO. 08 • $9.90 features 40WHEN AUTUMN LEAVES FALL, COLORFUL OPPORTUNITIES ARISE Tricks of the trade when marketing produce for the season. 46GAME ON! Produce can be the life of the tailgate party. 40 52WASHINGTON APPLES RADIATE From Ambrosia to Breeze, a full pipeline of cover story special features varieties shines from the Evergreen State. 2725TH ANNUAL MARKETING 16FROM THE PAGES OF THE 60TRADE PACKAGING EXCELLENCE AWARDS PRODUCEBUSINESSUK.COM MOLDS TO CONSUMER DEMAND Produce Business Recognizes 17 Outstanding Campaigns Squeezed Middle Ground Is Convenience is key, and industry players More Of An Issue For Retailers are meeting needs in various ways. 20 commentary ASCENDENT INDEPENDENTS: 10 THE FRUITS OF THOUGHT MURPHY’S MARKETPLACE Will California’s Drought Cause Customers experience local flavor departments Industry’s Positive Reputation and aesthetics in this New Jersey ORGANIC MARKET To Dry Up? independent retailer. 64 WORKING THROUGH THE CHALLENGES OF ORGANIC SUPPLY 86 RETAIL PERSPECTIVE 22 Using specialized organic distributors Take Another Look At RESTROSPECTIVE can smooth out the supply chain and In-Store Processing Retailer-Turned-Supplier, maintain consistency. Brian Gannon’s Career 87 WHOLESALE MARKET Spans More Than 30 Years MERCHANDISING REVIEW Are Trade Shows Still Relevant? 71 8 TACTICS TO CONSIDER WHEN MERCHANDISING ONIONS 88 EUROPEAN MARKET This popular item can drive sales The Significance Of The throughout produce and beyond. US/EU Transatlantic Trade in this issue & Investment Partnership 4 QUIZ 78 MUSHROOMS ON THE MOVE By touting the health benefits and 89 VOICE OF THE INDUSTRY 8 PRODUCE WATCH including value-added lines, retailers Adapting To Trends And Coding can position these products to sell. -

Asparagus, Its Culture for Home Use and for Market / a Practical Treatise

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Asparagus, its culture for home use and for market:, by F. M. Hexamer This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Asparagus, its culture for home use and for market: a practical treatise on the planting, cultivation, harvesting, marketing, and preserving of asparagus, with notes on its history Author: F. M. Hexamer Release Date: March 14, 2010 [EBook #31643] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ASPARAGUS, ITS CULTURE *** Produced by Tom Roch, Matt Whittaker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images produced by Core Historical Literature in Agriculture (CHLA), Cornell University) Transcriber's Note: Obvious typos were fixed and use of hyphens was normalized throughout, but all other spelling and punctuation was retained as it appeared in the original text. ASPARAGUS ITS CULTURE FOR HOME USE AND FOR MARKET A PRACTICAL TREATISE ON THE PLANTING, CULTIVATION, HARVESTING, MARKETING, AND PRESERVING OF ASPARAGUS, WITH NOTES ON ITS HISTORY AND BOTANY BY F. M. HEXAMER ILLUSTRATED NEW YORK ORANGE JUDD COMPANY 1914 Printed in U. S. A. BEGINNING OF THE ASPARAGUS INDUSTRY IN CALIFORNIA TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE PREFACE vi I. Historical Sketch 1 II. Botany 4 III. Cultural Varieties 17 IV. Seed Growing 26 V. The Raising of Plants 30 VI. Selection of Plants 38 VII. -

Plant Introductions N.E

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange South Dakota State University Agricultural Bulletins Experiment Station 5-1-1927 Plant Introductions N.E. Hansen Follow this and additional works at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/agexperimentsta_bulletins Recommended Citation Hansen, N.E., "Plant Introductions" (1927). Bulletins. Paper 224. http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/agexperimentsta_bulletins/224 This Bulletin is brought to you for free and open access by the South Dakota State University Agricultural Experiment Station at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulletins by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INDEX Pa1re Paire Adno Apple --------------------------- 8 Kahinta Plum ----------------------- 23 Alexis Crabapple ---------------------- 8 Kamdesa S. C. Hybrid _________________ 28 Amdo Rose -------------------------- 50 Kana Gooseberry --------------------- 44 Amur Crabapple --------------------- 8 Kanega Gooseberry ------------------- 44 Anoka Apple ------------------------ 9 Kapoza Gooseberry ------------------ 44 Arika.ra Grape ----------------------- 39 Kataga Gooseberry ------------------ 44 Assiniboin Plum --------------------- 20 Kawanka Gooseberry ----------------- 44 Atkan Grape ------------------------ -

Asparagus Beetle Factsheet

Common and spotted asparagus Eggs are firmly attached to the plant and do not wash off easily with water. Larvae hatch after 3-8 days and beetle as pests of asparagus begin feeding on the plant (Fig 1C). Larvae are pale grey or cream-colored with a dark head. Larvae drop By Amanda L. Buchanan, William R. Morrison III, into the soil to pupate, and emerge as adults after 10- Ben Werling, Adam J. Ingrao and Zsofia Szendrei 14 days. A single generation from egg to adult is roughly 30 days, allowing for three generations per Appearance and life cycle: Both common and spotted year in Michigan (Fig 2). asparagus beetle feed exclusively on asparagus, but the common asparagus beetle is much more abundant in Spotted asparagus beetle life cycle is similar to the fields. common asparagus beetle, but adults emerge later in the season. Adult coloration is orange-red with 12 (A) black spots (Fig 1D). Light-colored eggs are deposited singly on stems, and can be difficult to find. Larvae are difficult to distinguish from the common asparagus beetle. (B) (C) (D) Figure 1. Common asparagus beetle (A) adults, (B) eggs, (C) larva, and spotted asparagus beetle adults (D). Common asparagus Figure 2. Life cycle of the common asparagus beetle. Photo credit: beetles are significant pests of asparagus; spotted asparagus beetles W.R. Morrison III; pupa image: Bernice DeMarco, Michigan State University cause little damage. Photo credit: W.R. Morrison III Damage: Common asparagus beetles cause pitted Common asparagus beetle adults overwinter in scars on spears, stems, and ferns (Fig 3), which asparagus stems and field debris within and outside decreases the market value of spears during harvest asparagus fields. -

Asparagus (Asparagus Officinalis)

Asparagus (Asparagus officinalis) Asparagus (Asparagus officinalis) is an attractive, delicious, and nutritious perennial vegetable that can produce spears for 10-15 years once a bed is established. It is a hardy, cool- loving crop that sends spears out of the ground when soil temperatures are above 50 degrees F. The plant does best in full sun to part shade. Asparagus plants are dioecious which means that the male and female flowers are borne on different plants. The preferred male plants live longer, emerge earlier in the spring, and do not produce fruit that will compete with the roots and crown for nutrients. The female plant produces red berries in summer. The energy used for producing fruit reduces the amount and size of spears, which is why male plants are preferred. The asparagus plant will grow into a fern if the shoots/spears are not harvested. An established plant can produce 1/2 pound of spears per foot of row in spring and early summer with planned harvesting. Asparagus is a low calorie, high fiber food that contains Vitamins A, C, K and folate. Growing Conditions • Asparagus grows best in well-drained loamy soil. Asparagus roots that sit in water-logged soil may develop root/crown rot. • Plants prefer a soil pH of 6.5-7.5 and will do poorly if the soil pH is less than 6.0. Prior to planting, send soil samples to the UConn Soil Nutrient Analysis Laboratory to determine nutrient levels and if limestone should be added prior to planting. • Plants should be located in frost-free areas since young spears can be damaged by frost or light freezes.