'Arabesque' Furniture in Khedival Cairo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY in CAIRO School of Humanities And

1 THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY IN CAIRO School of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations Islamic Art and Architecture A thesis on the subject of Revival of Mamluk Architecture in the 19th & 20th centuries by Laila Kamal Marei under the supervision of Dr. Bernard O’Kane 2 Dedications and Acknowledgments I would like to dedicate this thesis for my late father; I hope I am making you proud. I am sure you would have enjoyed this field of study as much as I do. I would also like to dedicate this for my mother, whose endless support allowed me to pursue a field of study that I love. Thank you for listening to my complains and proofreads from day one. Thank you for your patience, understanding and endless love. I am forever, indebted to you. I would like to thank my family and friends whose interest in the field and questions pushed me to find out more. Aziz, my brother, thank you for your questions and criticism, they only pushed me to be better at something I love to do. Zeina, we will explore this world of architecture together some day, thank you for listening and asking questions that only pushed me forward I love you. Alya’a and the Friday morning tours, best mornings of my adult life. Iman, thank you for listening to me ranting and complaining when I thought I’d never finish, thank you for pushing me. Salma, with me every step of the way, thank you for encouraging me always. Adham abu-elenin, thank you for your time and photography. -

What's Open Now in Cairo (Pdf)

Categories: News (../advanced-search/?category=news), Destinations (../advanced- search/?category=destinations) What’s Open Now in Cairo Egypt is open to US travelers and its capital, Cairo awaits with freshly re-opened luxury hotels, museums and awe-inspiring monuments Oct 02 2020 by Gretchen Kelly Ed Note: As international travel begins to recover, Business Traveler USA is exploring opportunities now available to US travelers in Morocco, Turkey, Egypt and beyond, with Kenn Laya, CEO of Vuitton Travel, (https://vuittontravel.com) a bespoke travel concierge service. In the third installment (https://www.businesstravelerusa.com/business-traveler- usa-story/talking-turkey-cappadocia-and-beyond)of this four-part series, Kenn guided us through regions of Turkey beyond. Today’s adventure takes us to Egypt, which is open for tourism from the US. Kenn outlines what it takes to get there, and shares the best of what’s open in Cairo to put on your must-do list. BT: What is the safest, fastest way for Americans to travel to Egypt now? / Laya: I would recommend Egypt Air, (https://www.egyptair.com) a Star Alliance member, it is the most direct service with ights from Washington, New York and Toronto. As COVID-19 recovery expands that network of ights may increase. To y Egypt Air, you must have a COVID-19 negative test 48 hours ahead of time and wear a mask on board. The airline is taking steps to socially distance ights. They are not selling capacity ights at the moment. The New York to Cairo route features the Dreamliner. Once you get to Cairo there will be a health check for foreign nationals. -

The Published Correspondences of Ignaz Goldziher

The Published Correspondences of Ignaz Goldziher Kinga D´ev´enyi and Sabine Schmidtke∗ 1 Introduction When Ignaz Goldziher passed away on November 13, 1921, he left behind a cor- pus of scientific correspondence of over 13,000 letters from about 1,650 persons, in ten languages. His Nachlass, including the letters as well as his hand-written notes and works, was bequeathed to the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The corpus, which is freely accessible in its entirety in digital form1 constitutes the single most important source informing about the history of Arabic, Jewish, and Islamic studies and cognate fields during Goldziher‘s time. Selected portions of the Goldziher correspondence are available in critical editions, while other por- tions have been consulted for studies on the history of the field, but the bulk of the material has as yet remained untapped. This inventory aims to provide an overview of those parts of the correspondence which are available in publication, as well as of studies based on the correspondence. 2 General Studies Berzeviczy, Albert, "A Goldziher-f´elelevelez´es-gy˝ujtem´eny t¨ort´enet´ehez," [On the history of the Goldziher correspondence, in Hungarian] Akad´emiai Ertes´ıt˝o´ 43 (1933), pp. 347-348 D´ev´enyi, Kinga, "From Algiers to Budapest: The Letters of Mohamed Ben Cheneb to Ignaz Goldziher" [also containing a general overview of the correspondence], The Arabist: Budapest Studies in Arabic, 39 (2018), pp. 11-32 <https://eltearabszak.hu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/The-Arabist-_ -Budapest-Studies-in-Arabic-39-_-2018-3.pdf> ∗Licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 Unported Licence. -

Max Herz Pasha Research Institute and Conservation School

IPARTANSZÉK complex/diploma design 2018/2019 spring www.ipar.bme.hu CX + DIP / 2018-2019 spring /// 2nd brief 03.01.2019 //////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// IPARTANSZÉK CX + DIP / 2018-2019 spring /// 2nd brief 03.01.2019 //////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// IPARTANSZÉK PALOZNAK revitalization of a former farm building CX + DIP / 2018-2019 spring /// 2nd brief 03.01.2019 //////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// IPARTANSZÉK The site and surroundings offer good possibility for active recreation. The extraordinary conditions of lake Balaton and the Balaton Uplands area offer a variety of programs even for a longer vacation. Beside the program possibilities directly related to the lake, there is a variety of walking and biking tours. Furthermore there is a unique possibility for getting acquainted with the local gastronomy and the wine selection of the North-Balaton wine region. CX + DIP / 2018-2019 spring /// 2nd brief 03.01.2019 //////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// IPARTANSZÉK CX + DIP / 2018-2019 spring /// 2nd brief 03.01.2019 -

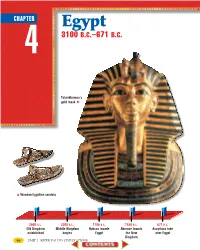

Chapter 4: Egypt, 3100 B.C

0066-0081 CH04-846240 10/24/02 5:57 PM Page 66 CHAPTER Egypt 4 3100 B.C.–671 B.C. Tutankhamen’s gold mask ᭤ ᭡ Wooden Egyptian sandals 2600 B.C. 2300 B.C. 1786 B.C. 1550 B.C. 671 B.C. Old Kingdom Middle Kingdom Hyksos invade Ahmose founds Assyrians take established begins Egypt the New over Egypt Kingdom 66 UNIT 2 RIVER VALLEY CIVILIZATIONS 0066-0081 CH04-846240 10/24/02 5:57 PM Page 67 Chapter Focus Read to Discover Chapter Overview Visit the Human Heritage Web site • Why the Nile River was so important to the growth of at humanheritage.glencoe.com Egyptian civilization. and click on Chapter 4—Chapter • How Egyptian religious beliefs influenced the Old Kingdom. Overviews to preview this chapter. • What happened during Egypt’s Middle Kingdom. • Why Egyptian civilization grew and then declined during the New Kingdom. • What the Egyptians contributed to other civilizations. Terms to Learn People to Know Places to Locate shadoof Narmer Nile River pharaoh Ahmose Punt pyramids Thutmose III Thebes embalming Hatshepsut mummy Amenhotep IV legend hieroglyphic papyrus Why It’s Important The Egyptians settled in the Nile River val- ley of northeast Africa. They most likely borrowed ideas such as writing from the Sumerians. However, the Egyptian civiliza- tion lasted far longer than the city-states and empires of Mesopotamia. While the people of Mesopotamia fought among themselves, Egypt grew into a rich, powerful, and unified kingdom. The Egyptians built a civilization that lasted for more than 2,000 years and left a lasting influence on the world. -

Timeline .Pdf

Timeline of Egyptian History 1 Ancient Egypt (Languages: Egyptian written in hieroglyphics and Hieratic script) Timeline of Egyptian History 2 Early Dynastic Period 3100–2686 BCE • 1st & 2nd Dynasty • Narmer aka Menes unites Upper & Lower Egypt • Hieroglyphic script developed Left: Narmer wearing the crown of Lower Egypt, the “Deshret”, or Red Crown Center: the Deshret in hieroglyphics; Right: The Red Crown of Lower Egypt Narmer wearing the crown of Upper Egypt, the “Hedjet”, or White Crown Center: the Hedjet in hieroglyphics; Right: The White Crown of Upper Egypt Pharaoh Djet was the first to wear the combined crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, the “Pschent” (pronounced Pskent). Timeline of Egyptian History 3 Old Kingdom 2686–2181 BCE • 3rd – 6th Dynasty • First “Step Pyramid” (mastaba) built at Saqqara for Pharaoh Djoser (aka Zoser) Left: King Djoser (Zoser), Righr: Step pyramid at Saqqara • Giza Pyramids (Khufu’s pyramid – largest for Pharaoh Khufu aka Cheops, Khafra’s pyramid, Menkaura’s pyramid – smallest) Giza necropolis from the ground and the air. Giza is in Lower Egypt, mn the outskirts of present-day Cairo (the modern capital of Egypt.) • The Great Sphinx built (body of a lion, head of a human) Timeline of Egyptian History 4 1st Intermediate Period 2181–2055 BCE • 7th – 11th Dynasty • Period of instability with various kings • Upper & Lower Egypt have different rulers Middle Kingdom 2055–1650 BCE • 12th – 14th Dynasty • Temple of Karnak commences contruction • Egyptians control Nubia 2nd Intermediate Period 1650–1550 BCE • 15th – 17th Dynasty • The Hyksos come from the Levant to occupy and rule Lower Egypt • Hyksos bring new technology such as the chariot to Egypt New Kingdom 1550–1069 BCE (Late Egyptian language) • 18th – 20th Dynasty • Pharaoh Ahmose overthrows the Hyksos, drives them out of Egypt, and reunites Upper & Lower Egypt • Pharaoh Hatshepsut, a female, declares herself pharaoh, increases trade routes, and builds many statues and monuments. -

The Cairo Street at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893

Nabila Oulebsir et Mercedes Volait (dir.) L’Orientalisme architectural entre imaginaires et savoirs Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 István Ormos DOI: 10.4000/books.inha.4915 Publisher: Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art Place of publication: Paris Year of publication: 2009 Published on OpenEdition Books: 5 December 2017 Serie: InVisu Electronic ISBN: 9782917902820 http://books.openedition.org Electronic reference ORMOS, István. The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 In: L’Orientalisme architectural entre imaginaires et savoirs [online]. Paris: Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art, 2009 (generated 18 décembre 2020). Available on the Internet: <http://books.openedition.org/ inha/4915>. ISBN: 9782917902820. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.inha.4915. This text was automatically generated on 18 December 2020. The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 1 The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 István Ormos AUTHOR'S NOTE This paper is part of a bigger project supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA T048863). World’s fairs 1 World’s fairs made their appearance in the middle of the 19th century as the result of a development based on a tradition of medieval church fairs, displays of industrial and craft produce, and exhibitions of arts and peoples that had been popular in Britain and France. Some of these early fairs were aimed primarily at the promotion of crafts and industry. Others wanted to edify and entertain: replicas of city quarters or buildings characteristic of a city were erected thereby creating a new branch of the building industry which became known as coulisse-architecture. -

Ignác Goldziher: Un Autre Orientalisme?, Paris 2011) • Ármin Vámbéry / Kinga Dévényi (In: the Arabist, Budapest 2015) • H

From a personal collection of nearly 13,500 letters to the WorldCat The correspondence of Ignaz Goldziher in the Oriental Collection of the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences Kinga Dévényi, Budapest 40th MELCom International, Budapest, 19‒21 June 2018 Ignaz Goldziher (1850-1921) Goldziher’s study in his home (4 Holló street, Budapest) His library formed the nucleus of what is today the Islam and Middle Eastern Collection in the National Library of Israel. Report of Turkologist Gyula Németh on the contents and scholarly value of the library of Alexander Kégl (RAL 1046/1925) Boxes containing the Goldziher correspondence The opening page from Goldziher’s planned edition – on the basis of the Leiden manuscript – of Tahdhib al-alfaz, a commentary by al-Tibrizi on Ibn al-Sikkit’s Kitab al-alfaz Mrs Ignaz Goldziher, Laura Mittler (1856-1925) She bequeathed Goldziher’s correspondence and his hand-written notes and works to the Academy Goldziher’s Home 4 Holló Street Orphanage for Jewish Boys 2 flats - Ignaz Goldziher - Samuel Kohn (1841-1920) historian and Chief Rabbi of Pest Jenő Balogh (1864-1953) Politician and Jurist Minister of Justice (1913-1917) Secretary General of the Academy 1920-1935 Sir Aurel Stein (1862-1943) Initiated the cataloguing of the Goldziher bequest Mathematician Károly Goldziher (1881-1955) He arranged the transfer of the Goldziher bequest to the Academy in 1926 and headed its cataloguing in 1931-33 A letter from Theodore Nöldeke (1836-1930) typed by Ms Csánki at the Secretariat of the Academy after office hours Arabic and Hebrew words written by Zs. -

The Secrets of Egypt & the Nile

the secrets of egypt & the nile 2021 - 2022 Dear Valued Guest, Egypt has captured the world’s imagination and continues to make an extraordinary impression on those who visit; and beginning in September 2021, we are delighted to take you there. While traveling along Egypt’s Nile River, you’ll be treated to a connoisseur’s discovery of this ancient civilization as only AmaWaterways can provide—with an unparalleled river cruise and land adventure that includes exquisite cuisine, beautiful accommodations, authentic excursions and extraordinary service. Your journey along the world’s longest river on board our spectacular, newly designed AmaDahlia will take you to some of Egypt’s most iconic sites. Discover ancient splendors such as the Great Hypostyle Hall of Karnak, the beguiling Temple of Luxor and the mystifying Valley of the Kings and Queens, along with exclusive access to the Tomb of Queen Nefertari. While in Cairo, you’ll stay at the 5-star Four Seasons at The First Residence, an oasis in the middle of the city, where each day, you’ll experience some of the world’s most astonishing antiquities. Come face to face with King Tut’s priceless discoveries at the Egyptian Museum, as well as the Great Sphinx and the three Pyramids of Giza, the last surviving of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World; and gain private access to Cairo’s Abdeen Presidential Palace. This mesmerizing destination has entranced archaeologists and historians for generations and inspired its own field of study—Egyptology. Now it’s time for you to be entranced. We look forward to sharing Egypt with you. -

The Egypt-Palestine/Israel Boundary: 1841-1992

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 1992 The Egypt-Palestine/Israel boundary: 1841-1992 Thabit Abu-Rass University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1992 Thabit Abu-Rass Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Human Geography Commons Recommended Citation Abu-Rass, Thabit, "The Egypt-Palestine/Israel boundary: 1841-1992" (1992). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 695. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/695 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EGYPT-PALESTINE/ISRAEL BOUNDARY: 1841-1992 An Abstract of a Thesis .Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the ~egree Master of Arts Thabit Abu-Rass University of Northern Iowa July 1992 ABSTRACT In 1841, with the involvement of European powers, the Ottoman Empire distinguished by Firman territory subject to a Khedive of Egypt from that subject more directly to Istanbul. With British pressure in 1906, a more formal boundary was established between Egypt and Ottoman Palestine. This study focuses on these events and on the history from 1841 to the present. The study area includes the Sinai peninsula and extends from the Suez Canal in the west to what is today southern Israel from Ashqelon on the Mediterranean to the southern shore of the Dead Sea in the east. -

State Violence, Mobility and Everyday Life in Cairo, Egypt

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Geography Geography 2015 State Violence, Mobility and Everyday Life in Cairo, Egypt Christine E. Smith University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Christine E., "State Violence, Mobility and Everyday Life in Cairo, Egypt" (2015). Theses and Dissertations--Geography. 34. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/geography_etds/34 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Geography at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Geography by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Evolution of Islamic Geometric Patterns

Frontiers of Architectural Research (2013) 2, 243–251 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com www.elsevier.com/locate/foar RESEARCH ARTICLE Evolution of Islamic geometric patterns Yahya Abdullahin, Mohamed Rashid Bin Embi1 Faculty of Built Environment, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor 81310, Malaysia Received 18 December 2012; received in revised form 27 March 2013; accepted 28 March 2013 KEYWORDS Abstract Islamic geometrical This research demonstrates the suitability of applying Islamic geometrical patterns (IGPs) to patterns; architectural elements in terms of time scale accuracy and style matching. To this end, a Islamic art; detailed survey is conducted on the decorative patterns of 100 surviving buildings in the Muslim Islamic architecture; architectural world. The patterns are analyzed and chronologically organized to determine the History of Islamic earliest surviving examples of these adorable ornaments. The origins and radical artistic architecture; movements throughout the history of IGPs are identified. With consideration for regional History of architecture impact, this study depicts the evolution of IGPs, from the early stages to the late 18th century. & 2013. Higher Education Press Limited Company. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction three questions that guide this work are as follows. (1) When were IGPs introduced to Islamic architecture? (2) When was For centuries, Islamic geometrical patterns (IGPs) have been each type of IGP introduced to Muslim architects and artisans? used as decorative elements on walls, ceilings, doors, (3) Where were the patterns developed and by whom? A domes, and minarets. However, the absence of guidelines sketch that demonstrates the evolution of IGPs throughout and codes on the application of these ornaments often leads the history of Islamic architecture is also presented.