Ormos István, Max Herz Pasha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY in CAIRO School of Humanities And

1 THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY IN CAIRO School of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations Islamic Art and Architecture A thesis on the subject of Revival of Mamluk Architecture in the 19th & 20th centuries by Laila Kamal Marei under the supervision of Dr. Bernard O’Kane 2 Dedications and Acknowledgments I would like to dedicate this thesis for my late father; I hope I am making you proud. I am sure you would have enjoyed this field of study as much as I do. I would also like to dedicate this for my mother, whose endless support allowed me to pursue a field of study that I love. Thank you for listening to my complains and proofreads from day one. Thank you for your patience, understanding and endless love. I am forever, indebted to you. I would like to thank my family and friends whose interest in the field and questions pushed me to find out more. Aziz, my brother, thank you for your questions and criticism, they only pushed me to be better at something I love to do. Zeina, we will explore this world of architecture together some day, thank you for listening and asking questions that only pushed me forward I love you. Alya’a and the Friday morning tours, best mornings of my adult life. Iman, thank you for listening to me ranting and complaining when I thought I’d never finish, thank you for pushing me. Salma, with me every step of the way, thank you for encouraging me always. Adham abu-elenin, thank you for your time and photography. -

The Published Correspondences of Ignaz Goldziher

The Published Correspondences of Ignaz Goldziher Kinga D´ev´enyi and Sabine Schmidtke∗ 1 Introduction When Ignaz Goldziher passed away on November 13, 1921, he left behind a cor- pus of scientific correspondence of over 13,000 letters from about 1,650 persons, in ten languages. His Nachlass, including the letters as well as his hand-written notes and works, was bequeathed to the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The corpus, which is freely accessible in its entirety in digital form1 constitutes the single most important source informing about the history of Arabic, Jewish, and Islamic studies and cognate fields during Goldziher‘s time. Selected portions of the Goldziher correspondence are available in critical editions, while other por- tions have been consulted for studies on the history of the field, but the bulk of the material has as yet remained untapped. This inventory aims to provide an overview of those parts of the correspondence which are available in publication, as well as of studies based on the correspondence. 2 General Studies Berzeviczy, Albert, "A Goldziher-f´elelevelez´es-gy˝ujtem´eny t¨ort´enet´ehez," [On the history of the Goldziher correspondence, in Hungarian] Akad´emiai Ertes´ıt˝o´ 43 (1933), pp. 347-348 D´ev´enyi, Kinga, "From Algiers to Budapest: The Letters of Mohamed Ben Cheneb to Ignaz Goldziher" [also containing a general overview of the correspondence], The Arabist: Budapest Studies in Arabic, 39 (2018), pp. 11-32 <https://eltearabszak.hu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/The-Arabist-_ -Budapest-Studies-in-Arabic-39-_-2018-3.pdf> ∗Licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 Unported Licence. -

Max Herz Pasha Research Institute and Conservation School

IPARTANSZÉK complex/diploma design 2018/2019 spring www.ipar.bme.hu CX + DIP / 2018-2019 spring /// 2nd brief 03.01.2019 //////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// IPARTANSZÉK CX + DIP / 2018-2019 spring /// 2nd brief 03.01.2019 //////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// IPARTANSZÉK PALOZNAK revitalization of a former farm building CX + DIP / 2018-2019 spring /// 2nd brief 03.01.2019 //////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// IPARTANSZÉK The site and surroundings offer good possibility for active recreation. The extraordinary conditions of lake Balaton and the Balaton Uplands area offer a variety of programs even for a longer vacation. Beside the program possibilities directly related to the lake, there is a variety of walking and biking tours. Furthermore there is a unique possibility for getting acquainted with the local gastronomy and the wine selection of the North-Balaton wine region. CX + DIP / 2018-2019 spring /// 2nd brief 03.01.2019 //////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// IPARTANSZÉK CX + DIP / 2018-2019 spring /// 2nd brief 03.01.2019 -

The Cairo Street at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893

Nabila Oulebsir et Mercedes Volait (dir.) L’Orientalisme architectural entre imaginaires et savoirs Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 István Ormos DOI: 10.4000/books.inha.4915 Publisher: Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art Place of publication: Paris Year of publication: 2009 Published on OpenEdition Books: 5 December 2017 Serie: InVisu Electronic ISBN: 9782917902820 http://books.openedition.org Electronic reference ORMOS, István. The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 In: L’Orientalisme architectural entre imaginaires et savoirs [online]. Paris: Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art, 2009 (generated 18 décembre 2020). Available on the Internet: <http://books.openedition.org/ inha/4915>. ISBN: 9782917902820. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.inha.4915. This text was automatically generated on 18 December 2020. The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 1 The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 István Ormos AUTHOR'S NOTE This paper is part of a bigger project supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA T048863). World’s fairs 1 World’s fairs made their appearance in the middle of the 19th century as the result of a development based on a tradition of medieval church fairs, displays of industrial and craft produce, and exhibitions of arts and peoples that had been popular in Britain and France. Some of these early fairs were aimed primarily at the promotion of crafts and industry. Others wanted to edify and entertain: replicas of city quarters or buildings characteristic of a city were erected thereby creating a new branch of the building industry which became known as coulisse-architecture. -

Ignác Goldziher: Un Autre Orientalisme?, Paris 2011) • Ármin Vámbéry / Kinga Dévényi (In: the Arabist, Budapest 2015) • H

From a personal collection of nearly 13,500 letters to the WorldCat The correspondence of Ignaz Goldziher in the Oriental Collection of the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences Kinga Dévényi, Budapest 40th MELCom International, Budapest, 19‒21 June 2018 Ignaz Goldziher (1850-1921) Goldziher’s study in his home (4 Holló street, Budapest) His library formed the nucleus of what is today the Islam and Middle Eastern Collection in the National Library of Israel. Report of Turkologist Gyula Németh on the contents and scholarly value of the library of Alexander Kégl (RAL 1046/1925) Boxes containing the Goldziher correspondence The opening page from Goldziher’s planned edition – on the basis of the Leiden manuscript – of Tahdhib al-alfaz, a commentary by al-Tibrizi on Ibn al-Sikkit’s Kitab al-alfaz Mrs Ignaz Goldziher, Laura Mittler (1856-1925) She bequeathed Goldziher’s correspondence and his hand-written notes and works to the Academy Goldziher’s Home 4 Holló Street Orphanage for Jewish Boys 2 flats - Ignaz Goldziher - Samuel Kohn (1841-1920) historian and Chief Rabbi of Pest Jenő Balogh (1864-1953) Politician and Jurist Minister of Justice (1913-1917) Secretary General of the Academy 1920-1935 Sir Aurel Stein (1862-1943) Initiated the cataloguing of the Goldziher bequest Mathematician Károly Goldziher (1881-1955) He arranged the transfer of the Goldziher bequest to the Academy in 1926 and headed its cataloguing in 1931-33 A letter from Theodore Nöldeke (1836-1930) typed by Ms Csánki at the Secretariat of the Academy after office hours Arabic and Hebrew words written by Zs. -

1 Adam Mestyan Curriculum Vitae Last Updated: November 1, 2020 EMPLOYMENT July 2019- Andrew W. Mellon Assistant Professor Of

1 Adam Mestyan Curriculum Vitae Last updated: November 1, 2020 EMPLOYMENT July 2019- Andrew W. Mellon Assistant Professor of History, Duke University. 2016-2019. Assistant Professor, History Department, Duke University. 2012-2013. Departmental Lecturer in the Modern History of the Middle East, Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford. FELLOWSHIPS 2018-2019. Fellow, Institut d’Études Avancées (Institute of Advanced Studies), Paris. 2016-2018. Foreign Research Fellow (membre scientifique à titre étranger), Institut français d’archéologie orientale (IFAO), Egypt. 2016-2021. “Freigeist” Fellowship, Volkswagen Stiftung (declined). 2013-2016. Junior Fellow, Society of Fellows, Harvard University. 2011-2012. “Europe in the Middle East – The Middle East in Europe” Post-Doctoral Fellow, Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin (Institute of Advanced Studies). EDUCATION Ph.D. 2011. History, Central European University (CEU). Ph.D. 2011. Art Theory, Eötvös Loránd University of Sciences (ELTE). M.A. 2007. Comparative History, CEU. Awarded with Distinction. M.A. 2005. Arabic and Semitic Philology, ELTE. M.A. 2004. Art Theory, ELTE. PUBLICATIONS Books Monographs Modern Arab Kingship – Constituting Nationhood and Islam Through Empire. Under contract. Arab Patriotism – The Ideology and Culture of Power in Late Ottoman Egypt. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017. Edited Volumes Primordial History, Print Capitalism, and Egyptology in Nineteenth-Century Cairo - Muṣṭafā Salāma al-Naǧǧārī’s The Garden of Ismail’s Praise. Cairo: Ifao, in press. Látvány/színház (Spectacle/Theatre – Genre, body, performativity), ed. by Ádám Mestyán and Eszter Horváth. Budapest: L’Harmattan, 2006 (in Hungarian). Peer-reviewed Articles “Muslim Dualism? – Inter-imperial History and Austria-Hungary in Ottoman Political Thought, 1867–1921.” Contemporary European History, forthcoming. -

Revival of Mamluk Architecture in the 19Th & 20Th Centuries

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2012 Revival of Mamluk architecture in the 19th & 20th centuries Laila Kamal Marei Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Marei, L. (2012).Revival of Mamluk architecture in the 19th & 20th centuries [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/873 MLA Citation Marei, Laila Kamal. Revival of Mamluk architecture in the 19th & 20th centuries. 2012. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/873 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY IN CAIRO School of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations Islamic Art and Architecture A thesis on the subject of Revival of Mamluk Architecture in the 19th & 20th centuries by Laila Kamal Marei under the supervision of Dr. Bernard O’Kane 2 Dedications and Acknowledgments I would like to dedicate this thesis for my late father; I hope I am making you proud. I am sure you would have enjoyed this field of study as much as I do. I would also like to dedicate this for my mother, whose endless support allowed me to pursue a field of study that I love. Thank you for listening to my complains and proofreads from day one. -

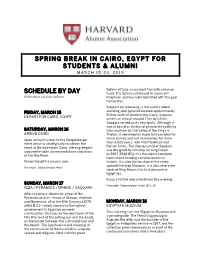

Spring Break in Cairo, Egypt for Students & Alumni

SPRING BREAK IN CAIRO, EGYPT FOR STUDENTS & ALUMNI MARCH 15- 23, 2019 Sphinx of Giza, a couchant lion with a human SCHEDULE BY DAY head. The Sphinx is believed to represent B=Breakfast, L=Lunch, D=Dinner Khephren and was later identified with the god Hamarkhis. Saqqara (or Sakkara), is the world's oldest FRIDAY, MARCH 15 standing step pyramid located approximately 30 km south of modern-day Cairo, Saqqara DEPART FOR CAIRO, EGYPT covers an area of around 7 km by 1.5 km. Saqqara served as its necropolis. Although it was eclipsed as the burial ground of royalty by SATURDAY, MARCH 16 Giza and later by the Valley of the Kings in ARRIVE CAIRO Thebes, it remained an important complex for Upon arrival transfer to the Steigenberger minor burials and cult ceremonies for more Hotel which is strategically located in the than 3,000 years, well into Ptolemaic and heart of the downtown Cairo, offering elegant Roman times. The step pyramid at Saqqara and comfortable accommodations and views was designed by Imhotep for King Djoser of the Nile River. (c.2667-2648 BC). It is the oldest complete hewn-stone building complex known in Dinner tonight is on your own. history. It is also the location of the newly opened Imhotep Museum. It is also where the Overnight: Steigenberger Hotel tomb of King Menes, the first pharaoh of Egypt lies Enjoy a festive welcome dinner this evening. SUNDAY, MARCH 17 Overnight: Steigenberger Hotel (B, L, D) GIZA / PYRAMIDS /SPHINX / SAQQARA After breakfast, depart for a tour of the Pyramids of Giza—those of Cheops, Kephren and Mycerinus, all of the IVth Dynasty (2575- MONDAY, MARCH 18 2465 B.C.)—which represent the highest EGYPTIAN MUSEUM achievement in Egyptian pyramid construction. -

Max Herz Pasha 1856–1919 His Life and Career

István Ormos Max Herz Pasha 1856–1919 His Life and Career I INSTITUT FRANÇAIS D’ARCHÉOLOGIE ORIENTALE Études urbaines 6/1 – 2009 – Le Caire TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME I AVANT-PROPOS ............................................................................................................................. V FOREWORD ..................................................................................................................................... VII Chapter I. LIFE ............................................................................................................................. 1 1. Childhood and Early Adolescence .................................................................................................. 1 2. The Budapest Years ......................................................................................................................... 2 3. The Vienna Years ............................................................................................................................. 4 4. Egypt ............................................................................................................................................... 10 4.1. The Journey to Egypt ............................................................................................................. 10 4.2. Egypt in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century ............................................................ 14 4.3. Julius Franz Pasha ................................................................................................................. -

The Four Madrasahs in the Complex of Sultan Hasan (1356-61)

HOWAYDA AL-HARITHY THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF BEIRUT The Four Madrasahs in the Complex of Sultan Ḥasan (1356–61): The Complete Survey The Complex of Sultan Ḥasan in Cairo is one of the most celebrated works of Mamluk architecture. Since the publication of the monograph entitled Mosquée du Sultan Hassan au Caire by Max Herz Pasha 1 in 1899, 2 several studies have addressed the building in terms of its typology, stylistic influence, patronage, and meaning. However, the monograph and the studies that followed remain without a complete survey of the four madrasahs attached to the complex. The ground floor plan of the complex, documented by the early monograph, reveals their essence and relationship to the main building but does not fully document the madrasahs as independent spatial units. This survey focuses on the four madrasahs and presents the results of a field survey with complete documentation of their floor plans and sections, published here for the first time (Figs. 1–20). 3 The drawings are supplemented in this introduction by a brief analysis and information pertaining to the assigned functions and personnel for the madrasahs provided by the waqf document of Sultan Ḥasan. 4 The complex had an elaborate functional program, with a bīmāristān, a sabīl- kuttāb, a congregational mosque, four madrasahs, and a mausoleum. Its plan follows the cruciform four-īwān type. Four great tunnel-vaulted īwāns flank the main ṣaḥn and constitute the major order of the complex. The four madrasahs are © Middle East Documentation Center. The University of Chicago. 1 Max Herz Pasha (1856–1919) was a Hungarian architect. -

A Walking Tour of Islamic Cairo: an Interactive Slide Lecture

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 451 115 SO 032 631 AUTHOR Stanik, Joseph T. TITLE A Walking Tour of Islamic Cairo: An Interactive Slide Lecture. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminars Abroad Program, 2000 (Egypt and Israel). SPONS AGENCY Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 39p.; Slides not available from ERIC. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Architecture; *Built Environment; Curriculum Enrichment; High Schools; Higher Education; *Islamic Culture; Middle Eastern History; *Municipalities; Simulation; Social Studies; Study Abroad; *Travel; World History IDENTIFIERS *Egypt (Cairo); Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; Walking Tours ABSTRACT This curriculum project, a lesson on Islamic Cairo, could be used in a unit on Islamic civilization in an advanced placement high school world history or world civilization course, or it could be used in a college level Middle Eastern history or Islamic civilization course. Upon completion of the lesson, students will be able to describe in writing the appearance and function of Islamic Cairo, a living example of a medieval Islamic city. The lesson takes the form of an interactive slide lecture, a simulated walking tour of 25 monuments in Islamic Cairo. The lesson strategy is described in detail, including materials needed and a possible writing assignment. The lesson first provides'a brief architectural history of Cairo and a short description of the different minaret styles found in Cairo. The lesson then addresses the slides, each representing a monument, and includes historical and architectural information and discussion questions for each. Contains 12 references. (BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Abbas Hilmi II and the Neo-Mamluk Style

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine International Conferences on Recent Advances 2010 - Fifth International Conference on Recent in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Soil Dynamics Engineering and Soil Dynamics 27 May 2010, 9:50 am - 10:20 am Architecture as an Expression of Identity: Abbas Hilmi II and the Neo-Mamluk Style Nadania Idriss School of Oriental and African Studies, Germany Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icrageesd Part of the Geotechnical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Idriss, Nadania, "Architecture as an Expression of Identity: Abbas Hilmi II and the Neo-Mamluk Style" (2010). International Conferences on Recent Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics. 1. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icrageesd/05icrageesd/session11/1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article - Conference proceedings is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Conferences on Recent Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARCHITECTURE AS AN EXPRESSION OF IDENTITY: ABBAS HILMI II AND THE NEO-MAMLUK STYLE Nadania Idriss School of Oriental and African Studies Lineinstr. 154 10115 Berlin, Germany ABSTRACT This paper examines the religious architecture that was built at the end of the nineteenth, beginning of the twentieth century, during the rule of Abbas Hilmi II (1892-1914).