Resisting Ages-Old Fixity As a Factor in Wine Quality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3.2 Mb PDF File

The Australian Wine Research Institute 2008 Annual Report Board Members The Company The AWRI’s laboratories and offices are located within an internationally renowned research Mr R.E. Day, BAgSc, BAppSc(Wine Science) The Australian Wine Research Institute Ltd was cluster on the Waite Precinct at Urrbrae in the Chairman–Elected a member under Clause incorporated on 27 April 1955. It is a company Adelaide foothills, on land leased from The 25.2(d) of the Constitution limited by guarantee that does not have a University of Adelaide. Construction is well share capital. underway for AWRI’s new home (to be com- Mr J.F. Brayne, BAppSc(Wine Science) pleted in October 2008) within the Wine Innova- Elected a member under Clause 25.2(d) The Constitution of The Australian Wine tion Cluster (WIC) central building, which will of the Constitution (until 12 November 2007) Research Institute Ltd (AWRI) sets out in broad also be based on the Waite Precinct. In this new terms the aims of the AWRI. In 2006, the AWRI building, AWRI will be collocated with The Mr P.D. Conroy, LLB(Hons), BCom implemented its ten-year business plan University of Adelaide and the South Australian Elected a member under Clause 25.2(c) Towards 2015, and stated its purpose, vision, Research and Development Institute. The Wine of the Constitution mission and values: Innovation Cluster includes three buildings which houses the other members of the WIC concept: Mr P.J. Dawson, BSc, BAppSc(Wine Science) Purpose CSIRO Plant Industry and Provisor Pty Ltd. Elected a member under Clause 25.2(d) of the To contribute substantially in a measurable Constitution way to the ongoing success of the Australian Along with the WIC parties mentioned, the grape and wine sector AWRI is clustered with the following research Mr T.W.B. -

Summer Wine List__2018.Pdf

Bonsoir, and welcome to Garden Court Restaurant. The list that follows has been put together to provide the widest range possible in wines and beverages to pair best with the menu that has been put together by our chefs. If you are unsure or wanting to try something a little bit different, please don’t hesitate to ask one of our knowledgeable ambassadors. APPERITIFS Cocktails Negroni l 18 Gimlet l 18 Campari, Vermouth, Tanqueray Tanqueray, Lime Juice Classic Martini l 18 Bellini l 18 Vodka/Tanqueray, Vermouth Prosecco, Peach Liqueur, Peach Puree Elderflower Spritz l 18 French 75 l 18 St. Germain, Prosecco, Soda, Mint Sparkling, Tanqueray, Lemon Juice Aperol Spritz l 18 Southside l 18 Aperol, Prosecco, Soda, Olives Tanqueray, Lime Juice, Mint Mojito l 18 Americano l 18 Bacardi, Lime Juice, Soda Campari, Vermouth, Soda Berry Sensation l 18 Spring Martini l 18 Berry Tea, Vodka, St. Germain, Berries Vodka, Green Tea, Lemon Juice Mocktails Apple Mojito l 12 Mango and Lime Fizz l 12 Apple Juice, Lime, Soda, Mint Mango Puree, Lime, Ginger Ale, Mint New South Wales Wine History The very first Australian vineyard was planted in New South Wales in 1791 with vines from settlements in South Africa. The vines were planted in the garden of Arthur Phillip, then Governor of the colony, in a site that is now the location of a hotel on Macquarie Street in Sydney. Phillip's early vineyard did not fare well in the hot, humid climate of the region and he sent a request to the British government for assistance in establishing viticulture in the new colony. -

Leacock's Rainwater

RAINWATER Leacock’s Madeira was established in 1760 and in 1925 formed the original Madeira Wine Association in partnership with Blandy’s Madeira. In 1989, the Symington family, renowned fourth generation Port producers, entered a partnership with Leacock’s in what had then become the Madeira Wine Company, which also represents Blandy’s, Cossart Gordon and Miles. The Blandy's family have continued to run Leacock's in the 21st century. THE WINEMAKING Fermentation off the skins with natural yeast at temperatures between 75°F and 78°F, in temperature controlled stainless steel tanks; fortification with grape brandy after approximately four days, arresting fermentation at the desired degree of sweetness. Leacock’s Rainwater was transferred to ‘estufa’ tanks where the wine underwent a cyclic heating and cooling process between 113°F and 122°F over a period of 3 months. After ‘estufagem’ the wine was aged for three years in American oak casks. The wine then underwent racking and fining before the blend was assembled and bottled. TASTING NOTE Topaz color with golden reflections. Characteristic Madeira bouquet of dried fruits, orange peels and notes of wood. Medium dry at first, followed by an attractive freshness of citrus flavors, with a long, luxurious finish. WINEMAKER STORAGE & SERVING Francisco Albuquerque Leacock’s Rainwater is excellent as an after dinner drink and also very GRAPE VARIETAL good with fruit, chocolate, cakes and Tinta Negra hard cheeses. WINE SPECIFICATION Alcohol: 18% vol Total acidity: 6.0 g/l tartaric acid Residual Sugar: 70 g/l SCORES UPC: 094799040019 90 Points, Wine Spectator, 2005 04.2021 Imported by Premium Port Wines Inc. -

Wine Industry Leadership Program Project

WINE INDUSTRY LEADERSHIP PROGRAM PROJECT FINAL REPORT to GRAPE AND WINE RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION Project Number: GWR 1001 Principal Investigator: Jill Briggs Research Organisation: Rural Training Initiatives P/L Date: 4th December 2012 Grape and Wine Research and Development Corporation Project Number – GWR101 Project Leader - Ms Jill Briggs Managing Director – Rural Training Initiatives Pty. Ltd. 1095 Kings Rd Norong VIC 3682 [email protected] The final report provides the wine industry with the following: a background to the need for leadership development in the Australian wine industry; the design and development of the 2012 - 2012 Wine Industry Leadership Program; the 2012 program outcomes; and some recommendations. Acknowledgment of funders: Project Funder – Grape and Wine Research and Development Corporation Report Date: December 2012 Disclaimer: Any recommendations contained in this publication do not necessarily represent current Grape and Wine Research and Development Corporation policy. No person should act on the basis of the contents of this publication, whether as to matters of fact or opinion or other content, without first obtaining specific, independent professional advice in respect of the matters set out in this publication. Table of Contents 1 Abstract ............................................................................................................... 2 2 Executive Summary ........................................................................................... 3 3. Background -

Jancis Robinson

The Great Island Madeira Tasting 5 May 2010 by Jancis Robinson These pictures show just part of the archive of sales ledgers bequeathed to the Madeira Wine Company by Noel Cossart, author of one of the most authoritative books on the wine (along with Alex Liddell's more recent work). They date from 1774, 21 years before the oldest wine we tasted was made, and seem to me to illustrate most appropriately the historic nature of this extraordinary drink. The notes below on 43 of the finest madeiras back to 1795 were taken at an extraordinary tasting on the island last week described in The miracle of madeira and What a tasting! The notes are presented in the order the wines were served, which was dictated strictly by age rather than sweetness level. In fact one of the more extraordinary things about these wines was how few of them tasted particularly sweet. Presumably the explanation lies in these wines' exceptionally high levels of acidity. Most of the wines were labelled with the names of the four best-known classic grapes of Madeira - Sercial, Verdelho, Boal and Malvasia - but we also tasted four Terrantez, which demonstrated just how very firm and long-lived wines made from this variety are, and a Bastardo. One of the younger Blandys is planting Terrantez once more. Barbeito made a few hundred litres of Bastardo in 2007 but in 2008 yields were almost non existent. 'I'm learning', said Ricardo Diogo Freitas. 'At the beginning, everything is bad with Bastardo.' My suggested drinking dates are even more speculative than usual in these tasting notes, not least because madeira lasts so many decades, and many of the wines are just so old. -

Sadie Heckenberg Thesis

!! ! "#$%&"'!()#*$!*+! ,&$%#*$!*+!! !"#$%&$'()*+(,')%(#-.*/(#01%,)%.* $2"#-)2*3"41*5'.$#"'%.*4(,*6-1$-"4117*849%* :%.%4"&2* !"4&$'&%.** * * * Sadie Heckenberg BA Monash, BA(Hons) Monash Swinburne University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Of Doctor of Philosophy July 2018 #$%&'#(&!! ! ! ! Indigenous oral history brings life to our community narratives and portrays so well the customs, beliefs and values of our old people. Much of our present day knowledge system relies on what has been handed down to us generation after generation. Learning through intergenerational exchange this Indigenous oral history research thesis focuses on Indigenous methodologies and ways of being. Prime to this is a focus on understanding cultural safety and protecting Indigenous spoken knowledge through intellectual property and copyright law. From an Indigenous and Wiradjuri perspective the research follows a journey of exploration into maintaining and strengthening ethical research practices based on traditional value systems. The journey looks broadly at the landscape of oral traditions both locally and internationally, so the terms Indigenous for the global experience; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander for the Australian experience; and Wiradjuri for my own tribal identity are all used within the research dialogue. ! ! "" ! #$%&'()*+,-*&./" " " " First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge and thank the Elders of the Wiradjuri Nation. Without their knowledge, mentorship and generosity I would not be here today. Most particularly my wonderful Aunty Flo Grant for her guidance, her care and her generosity. I would like to thank my supervisors Professor Andrew Gunstone, Dr Sue Anderson and Dr Karen Hughes. Thank you for going on this journey of discovery and reflection with me. -

Proudly Family Owned for 160 Years, Tyrrell¼s Is a Wine Company Rich in History and Pioneering Achievements. the Tyrrell Family

8ZW]LTaNIUQTaW_VMLNWZaMIZ[<aZZMTT¼[Q[I_QVMKWUXIVa ZQKPQVPQ[\WZaIVLXQWVMMZQVOIKPQM^MUMV\[<PM<aZZMTTNIUQTa¼[ I[[WKQI\QWV_Q\P\PMOZIXMJMOIV_Q\P-L_IZL<aZZMTTQV <WLIaPQ[TMOIKaTQ^M[WV\PZW]OP\PMNW]Z\PIVLÅN\POMVMZI\QWVWN \PMNIUQTa_PWKWTTMK\Q^MTaUIVIOMWVMWN )][\ZITQI¼[WTLM[\IVL most highly regarded wineries. Tyrrell’s has grown over a century and out of the Hunter Valley, setting up a half to become one of Australia’s vineyards 160kms north of Sydney most prestigious wineries. Today and 100kms north of Melbourne. the company is managed by fourth Innovation and leadership are generation owner Bruce Tyrrell and two of the key attributes of the his children, John, Chris and Jane. family, and have been instrumental Over the years the family have been in securing Tyrrell’s position as one instrumental in changing the face of Australia’s leading wineries. Today of the Australian wine industry. The the family are also producers of family’s many successes include Australia’s most awarded white wine, introducing Chardonnay and Pinot the ‘Vat 1 Hunter Valley Semillon’, Noir to the Australian wine category, which has won an astounding and their ‘Vat 47’ was Australia’s first 5,475 medals and 332 trophies. commercial Chardonnay. They were also one of the first wineries to expand 102 A The Tyrrell’s are also members wine’s name is inspired by the lunar of ‘Australia’s First Families of calendar which is the vigneron’s Wine (AFFW)’, an organistion timepiece that signals when to harvest, that communicates and builds when to cellar and when to enjoy. awareness of premium Australian wines and their heritage. -

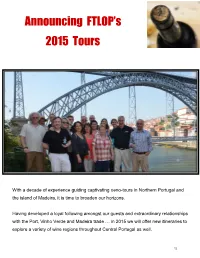

Announcing FTLOP's 2015 Tours

Announcing FTLOP’s 2015 Tours With a decade of experience guiding captivating oeno-tours in Northern Portugal and the island of Madeira, it is time to broaden our horizons. Having developed a loyal following amongst our guests and extraordinary relationships with the Port, Vinho Verde and Madeira trade … in 2015 we will offer new itineraries to explore a variety of wine regions throughout Central Portugal as well. 12 JOIN US FOR A ONCE-IN-A-LIFETIME EXPERIENCE! A brief bio on your two hosts: Mario Ferreira: Mario is from Alcobaça, Portugal and majored in Social Communication and Marketing. From 1998-2004 he worked for the Port wine industry while living in the USA: having spent one year as “Sandeman Port Wine Ambassador” and followed by five years in the marketing department of the Port Wine Institute (IVP/IVDP). In 2005, Mario decided to further explore adventures on the African continent and seek out business opportunities there as well. Nowadays, he spends most of his time traveling throughout a variety of countries in Africa, while consulting for a Spanish-based company (non-wine/beverage related). Also in 2005, Mario partnered with Roy to develop and co-host bespoke Port, Douro and Madeira wine and food explore-vacations that have begun to branch out to other regions of Portugal. Mario remains committed to FTLOP’s oenotourism program and together, he and Roy have brought nearly two dozen groups to visit his country. 13 Roy Hersh: Roy’s experience in food and wine industry management has spanned more than three decades and includes consulting for restaurants, country clubs, casinos, and a variety of wine-related ventures. -

NSW Food & Wine Tourism Strategy & Action Plan 2018

New South Wales Food & Wine Tourism Strategy & Action Plan 2018 - 2022 FOREWORD The NSW Food & Wine Tourism Strategy & Action Plan 2018 - 2022 is designed to provide the food and wine sector and the tourism industry with an overview of Destination NSW’s plans to further support the development of food and wine tourism to the State. NSW attracts more domestic and international visitors than any Australian State, giving us a position of strength to leverage in growing consumer interest and participation in food and wine tourism experiences. The lifeblood of this vibrant industry sector is the passion and innovation of our producers, vignerons, chefs and restaurateurs and the influence of our multicultural population on ingredients, cooking styles and cuisine and beverage purveyors. NSW is also home to the oldest and newest wine regions in Australia, world renowned for vintages of exceptional quality. From fifth-generation, family-owned wineries to a new generation of winemakers experimenting with alternative techniques and varietals, the State’s wine industry is a key player in the tourism industry. Alongside our winemakers, a new breed of beverage makers – the brewers of craft beer and ciders and distillers of gin and other spirits – is enriching the visitor experience. The aim of this Strategy & Action Plan is to ensure NSW’s exceptional food and wine experiences become a highlight for visitors to the State. Destination NSW is grateful to the many industry stakeholders who have contributed to the development of this Strategy and Action Plan, and we look forward to working together to deliver outstanding food and wine experiences to every visitor. -

Wine Vine Cultivation Vinification Vine Varieties Types Of

INDEX Madeira Island Madeira Wine, a secular history “Round Trip” Wine Vine Cultivation Vinification Vine Varieties Types of Madeira Wine Madeira Wine at your table The Wine, Embroidery and Handicraft Institute of Madeira The Wine Sector Control and Regulation Directorate The Vitiviniculture Directorate The Quality Support Directorate The Promotion Services Confraria do Vinho da Madeira Marketing Instituto do Vinho, do Bordado e do Artesanato da Madeira, I.P. 1 MADEIRA, THE ISLAND Madeira is a gift from nature. Its landscape displays a perfect continuum and symbiosis between sea and forest, mountains and valleys. Writing about Madeira is to reveal its roots, its culture and its traditions. It is the absorption of unique knowledge, textures and tastes. It is the Island of flowers, of hot summers and mild winters. The island, a part of Portugal, lies in the Atlantic Ocean and, together with the Island of Porto Santo, the Desertas and the Selvagens Islands, makes up the Archipelago of Madeira. The profoundly rooted viticultural landscape of the island is a stage where a myriad of ever-changing colours, from different hues green to reddish-browns, play their part as the year goes by. The building of terraces, upheld with walls of stone, reminds the observer of staircases which, in some parts of the island, go all the way from sea level to the brim of the mountain forests and resemble gardens imbued in the landscape. Known in the whole world as a par excellence tourist destination, the notoriety of the Island of Madeira is also owed to the wine that bears its name and which, in the most various regions of the globe, gained fame and prestige. -

Blandy's Vintage Malmsey 1977

1977 VINTAGE MALMSEY THE FAMILY The Blandy’s family is unique for being the only family of all the original founders of the Madeira wine trade to still own and manage their original wine company. The family has played a leading role in the development of Madeira wine since the early nineteenth century. Blandy’s Madeira remains totally dedicated to the traditions, care, and craftsmanship of Madeira Wine for over 200 years. THE WINEMAKING The wine was aged for 41 years in old American oak casks at Quinta das Maravilhas in Funchal. “We bought the stock of wine after being presented with samples that far exceeded our expectations in terms of quality, freshness and complexity. Vintage Malmseys, when aged in the right location, have the ability to develop that natural richness into deep layers of aromas and flavors. The wine, after the years that it spent at the Zino’s family Quinta, benefited from the specific micro climate at that altitude. After we bought the wine, we held it at our winery in Caniçal before finally being bottled in May 2018.” This as the only wine produced and aged at Quinta das Maravilhas as subsequent harvests were sold as grapes to the Madeira Wine Association until the vineyard ceased to be productive. TASTING NOTE Dark mohogany color with golden refletions. A characteristic aroma of madeira wine, having prenaunced notes of exotic woods, dried and crystallized fruits and spices. On the mouth its full boddied, smooth, sweet releasing notes of dark chocolate, spices and tabaco, and has a long aftertaste with notes of fruitcake, molasses and spices. -

Sydney Printing

RARE BOOKS • MANUSCRIPTS • PAINTINGS • PRINTS • RARE BOOKS • MANUSCRIPTS • PAINTINGS • PRINTS HORDERN HOUSE HORDERN HOUSE 77 VICTORIA ST POTTS POINT SYDNEY NSW 2011 AUSTRALIA +612 9356 4411 www.hordern.com JULY 2011 Sydney Printers before 1860 chiefly from the Robert Edwards library. [email protected] Hordern House recently received the wonderful library of Dr Robert Edwards AO, and over the next year or two we will be offering the library for sale. Bob is one of the great figures of Australian cultural history, at different times working as a leading anthropologist, a central figure in the study of indigenous art, a museum director and a driving force behind many of the international blockbuster art shows to travel to Australia. His early training as an anthropologist saw him doing fieldwork in remote Australia, and led to him becoming a museum curator in the 1960s and 70s. He was the founding director of the Australia Council’s Aboriginal Arts Board, perhaps most famous for its support of the Papunya Tula artists. He was the Director of the Museum of Victoria from 1984-90, the founding chairman of the National Museum of Australia and the founding chairman of the National Portrait Gallery. He has also for many years been the chief executive of Art Exhibitions Australia which brought to Australia significant exhibitions, including the Entombed Warriors from China (1982), Claude Monet (1985), Van Gogh (1993) and Rembrandt (1997). Bob is an ardent bibliophile, and his Library reflects the discerning taste of a knowledgeable and educated collector. Some books are of such rarity that they are known in only a handful of copies, and his collection embraces early Australian printing, early works on the Australian Aborigines, the major early voyage accounts, as well as works on early settlement and inland exploration.