Architecture of Uncertainty in Poland, 1945—

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Fernando Botero

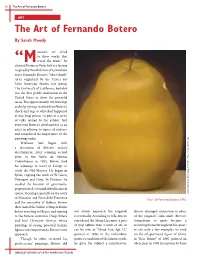

36 The Art of Fernando Botero ART The Art of Fernando Botero By Sarah Moody useums are afraid to show works that “Mreveal the truth.” So claimed Professor Peter Selz in a lecture inspired by the exhibition of Colombian artist Fernando Botero’s “Abu Ghraib” series organized by the Center for Latin American Studies last spring. The University of California, Berkeley was the fi rst public institution in the United States to show the powerful series. The approximately 100 drawings and oil paintings resulted from Botero’s shock and rage at what had happened at that Iraqi prison. As part of a series of talks related to the exhibit, Selz examined Botero’s development as an artist in relation to topics of violence and considered the importance of the paintings today. York. New Gallery, Image courtesy of Marlborough Botero. © Fernando Professor Selz began with a discussion of Botero’s artistic development. After winning second prize in the Salón de Artistas Colombianos in 1952, Botero used his winnings to travel to Europe to study the Old Masters. He began in Spain, copying the work of El Greco, Velázquez and Goya. In Florence, he studied the location of generously- proportioned, verisimilar bodies in real spaces, focusing especially on the work of Masaccio and Piero della Francesca “Pear” by Fernando Botero, 1976. and the sensuality of Rubens. Botero then visited the Sistine ceiling in Rome before traveling to Mexico and turning not always approach the originals almost deranged expression in place to the famous muralists Diego Rivera reverentially. According to Selz, Botero of the original’s calm smile. -

Zarys Historii Polonistyki W Ameryce Północnej BIBLIOTEKA POSTSCRIPTUM POLONISTYCZNEGO

Zarys historii polonistyki w Ameryce Północnej BIBLIOTEKA POSTSCRIPTUM POLONISTYCZNEGO Redaktorzy naukowi ROMUALD CUDAK, JOLANTA TAMBOR 2012 • TOM 2 Michał J. Mikoś Zarys historii polonistyki w Ameryce Północnej w opracowaniu MAŁGORZATY SMERECZNIAK ze wstępem BOŻENY SZAŁASTY-ROGOWSKIEJ i posłowiem WIOLETTY HAJDUK-GAWRON Uniwersytet Śląski w Katowicach Szkoła Języka i Kultury Polskiej Katedra Międzynarodowych Studiów Polskich Wersja elektroniczna: www.postscriptum.us.edu.pl Recenzent WACŁAW M. OSADNIK Korekta ZESPÓŁ Publikacja sfinansowana ze środków: UNIWERSYTETU ŚLĄSKIEGO W KATOWICACH Adres „Postscriptum Polonistyczne” Szkoła Języka i Kultury Polskiej UŚ pl. Sejmu Śląskiego 1, 40-032 Katowice tel./faks: +48 322512991, tel. 48 322009424 e-mail: [email protected] www.postscriptum.us.edu.pl Wydawca Uniwersytet Śląski w Katowicach Szkoła Języka i Kultury Polskiej Katedra Międzynarodowych Studiów Polskich Dystrybucja Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego ul. Bankowa 12B, 40-007 Katowice e-mail: [email protected]; www.wydawnictwo.us.edu.pl tel.: 48 32 3592056 Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego Wydawnictwo Gnome, Katowice Nakład: 250 egz. ISSN 1898-1593 Spis treści Bożena Szałasta-Rogowska: Pasja Hermesa ........................................................ 7 I. Rys historyczny ................................................................................................... 11 II. Obecność literatury polskiej w Ameryce Północnej i Anglii ..................... 36 III. Bibliografia tłumaczeń z literatury polskiej na angielski .......................... -

On the Threshold of the Holocaust: Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms In

Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. of the Holocaust carried out by the local population. Who took part in these excesses, and what was their attitude towards the Germans? The Author Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms Were they guided or spontaneous? What Tomasz Szarota is Professor at the Insti- part did the Germans play in these events tute of History of the Polish Academy in Occupied Europe and how did they manipulate them for of Sciences and serves on the Advisory their own benefit? Delving into the source Board of the Museum of the Second Warsaw – Paris – The Hague – material for Warsaw, Paris, The Hague, World War in Gda´nsk. His special interest Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Kaunas, this comprises WWII, Nazi-occupied Poland, Amsterdam – Antwerp – Kaunas study is the first to take a comparative the resistance movement, and life in look at these questions. Looking closely Warsaw and other European cities under at events many would like to forget, the the German occupation. On the the Threshold of Holocaust ISBN 978-3-631-64048-7 GEP 11_264048_Szarota_AK_A5HC PLE edition new.indd 1 31.08.15 10:52 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. -

Formalism Post- Formalism

FORMALISM POST- FORMALISM nonsite.org is an online, open access, peer-reviewed quarterly journal of scholarship in the arts and humanities 7 affiliated with Emory College of Arts and Sciences. 2014 all rights reserved. ISSN 2164-1668 EDITORIAL BOARD Bridget Alsdorf Ruth Leys James Welling Jennifer Ashton Walter Benn Michaels Todd Cronan Charles Palermo Lisa Chinn, editorial assistant Rachael DeLue Robert Pippin Michael Fried Adolph Reed, Jr. Oren Izenberg Victoria H.F. Scott Brian Kane Kenneth Warren SUBMISSIONS ARTICLES: SUBMISSION PROCEDURE Please direct all Letters to the Editors, Comments on Articles and Posts, Questions about Submissions to [email protected]. Potential contributors should send submissions electronically via nonsite.submishmash.com/Submit. Applicants for the B-Side Modernism/Danowski Library Fellowship should consult the full proposal guidelines before submitting their applications directly to the nonsite.org submission manager. Please include a title page with the author’s name, title and current affiliation, plus an up-to-date e-mail address to which edited text and correspondence will be sent. Please also provide an abstract of 100-150 words and up to five keywords or tags for searching online (preferably not words already used in the title). Please do not submit a manuscript that is under consideration elsewhere. 1 ARTICLES: MANUSCRIPT FORMAT Accepted essays should be submitted as Microsoft Word documents (either .doc or .rtf), although .pdf documents are acceptable for initial submissions.. Double-space manuscripts throughout; include page numbers and one-inch margins. All notes should be formatted as endnotes. Style and format should be consistent with The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed. -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

Pan Tadeusz by Adam Mickiewicz

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Pan Tadeusz by Adam Mickiewicz This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Pan Tadeusz Author: Adam Mickiewicz Release Date: [Ebook 28240] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PAN TADEUSZ*** PAN TADEUSZ OR THE LAST FORAY IN LITHUANIA All rights reserved PAN TADEUSZ OR THE LAST FORAY IN LITHUANIA A STORY OF LIFE AMONG POLISH GENTLEFOLK IN THE YEARS 1811 AND 1812 IN TWELVE BOOKS BY ADAM MICKIEWICZ TRANSLATED FROM THE POLISH BY GEORGE RAPALL NOYES 1917 LONDON AND TORONTO J. M. DENT & SONS LTD. PARIS: J. M. DENT ET FILS NEW YORK: E. P. DUTTON & CO. Contents PREFACE . 1 INTRODUCTION . 3 LIST OF THE PRINCIPAL CHARACTERS IN “PAN TADEUSZ” WITH NOTES ON POLISH PRONUN- CIATION . 14 BOOK I.—THE FARM . 17 BOOK II.—THE CASTLE . 45 BOOK III.—FLIRTATION . 69 BOOK IV—DIPLOMACY AND THE CHASE . 91 BOOK V.—THE BRAWL . 120 BOOK VI.—THE HAMLET . 146 BOOK VII.—THE CONSULTATION . 164 BOOK VIII.—THE FORAY . 181 BOOK IX.—THE BATTLE . 204 BOOK X—THE EMIGRATION. JACEK . 226 BOOK XI.—THE YEAR 1812 . 253 BOOK XII.—LET US LOVE ONE ANOTHER! . 273 NOTES . 299 [v] PREFACE THE present translation of Pan Tadeusz is based on the editions of Biegeleisen (Lemberg, 1893) and Kallenbach (Brody, 1911). I have had constantly by me the German translation by Lipiner (ed. -

They Fought for Independent Poland

2019 Special edition PISMO CODZIENNE Independence Day, November 11, 2019 FREE AGAIN! THEY FOUGHT FOR INDEPENDENT POLAND Dear Readers, The day of November 11 – the National Independence Day – is not accidentally associated with the Polish military uni- form, its symbolism and traditions. Polish soldiers on almost all World War I fronts “threw on the pyre their lives’ fate.” When the Polish occupiers were drown- ing in disasters and revolutions, white- and-red flags were fluttering on Polish streets to mark Poland’s independence. The Republic of Poland was back on the map of Europe, although this was only the beginning of the battle for its bor- ders. Józef Piłsudski in his first order to the united Polish Army shared his feeling of joy with his soldiers: “I’m taking com- mand of you, Soldiers, at the time when the heart of every Pole is beating stron- O God! Thou who from on high ger and faster, when the children of our land have seen the sun of freedom in all its Hurls thine arrows at the defenders of the nation, glory.” He never promised them any bat- We beseech Thee, through this heap of bones! tle laurels or well-merited rest, though. On the contrary – he appealed to them Let the sun shine on us, at least in death! for even greater effort in their service May the daylight shine forth from heaven’s bright portals! for Poland. And they never let him down Let us be seen - as we die! when in 1920 Poland had to defend not only its own sovereignty, but also entire Europe against flooding bolshevism. -

Warsaw in Short

WarsaW TourisT informaTion ph. (+48 22) 94 31, 474 11 42 Tourist information offices: Museums royal route 39 Krakowskie PrzedmieÊcie Street Warsaw Central railway station Shops 54 Jerozolimskie Avenue – Main Hall Warsaw frederic Chopin airport Events 1 ˚wirki i Wigury Street – Arrival Hall Terminal 2 old Town market square Hotels 19, 21/21a Old Town Market Square (opening previewed for the second half of 2008) Praga District Restaurants 30 Okrzei Street Warsaw Editor: Tourist Routes Warsaw Tourist Office Translation: English Language Consultancy Zygmunt Nowak-Soliƒski Practical Information Cartographic Design: Tomasz Nowacki, Warsaw Uniwersity Cartographic Cathedral Photos: archives of Warsaw Tourist Office, Promotion Department of the City of Warsaw, Warsaw museums, W. Hansen, W. Kryƒski, A. Ksià˝ek, K. Naperty, W. Panów, Z. Panów, A. Witkowska, A. Czarnecka, P. Czernecki, P. Dudek, E. Gampel, P. Jab∏oƒski, K. Janiak, Warsaw A. Karpowicz, P. Multan, B. Skierkowski, P. Szaniawski Edition XVI, Warszawa, August 2008 Warsaw Frederic Chopin Airport Free copy 1. ˚wirki i Wigury St., 00-906 Warszawa Airport Information, ph. (+48 22) 650 42 20 isBn: 83-89403-03-X www.lotnisko-chopina.pl, www.chopin-airport.pl Contents TourisT informaTion 2 PraCTiCal informaTion 4 fall in love wiTh warsaw 18 warsaw’s hisTory 21 rouTe no 1: 24 The Royal Route: Krakowskie PrzedmieÊcie Street – Nowy Âwiat Street – Royal ¸azienki modern warsaw 65 Park-Palace Complex – Wilanów Park-Palace Complex warsaw neighborhood 66 rouTe no 2: 36 CulTural AttraCTions 74 The Old -

Architecture, Form, Expression. the Helicoidal Skyscrapers'geometry

Bridges 2012: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture Architecture, Form, Expression. The Helicoidal Skyscrapers’Geometry Alessandra CAPANNA Dipartimento di Architettura e Progetto “Sapienza” Università di Roma Via Flaminia 359 - 00196 Roma, ITALY E-mail: [email protected] Mauro FRANCAVIGLIA Marcella G. LORENZI Dipartimento di Matematica, Laboratorio per la Comunicazione Scientifica Università di Torino Università della Calabria Via Carlo Alberto,10 - 10123 Torino, ITALY Cubo 30b, 87036 Arcavacata di Rende CS, E-mail: [email protected] ITALY E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Expressionist utopia of an Architect imitating the rigorous and -at the same time- extremely bizarre formative principles of Nature, linked with the engineering “must” of a coherent and correct structure are apparent antithesis if only played as the manifestation of an irrational and uncontrolled freedom. We explore the ancient idea of Harmony and Beauty and the historical confidence in the logarithmic spiral as the symbol of perfection in an un- built project for a 565 m (1,854 ft) high skyscraper that was supposed to be built on the tip of Manhattan, NYC. The role of geometry is no more exploited as an instrument for controlling architectural form, but for its liberation: the project for a helicoidal skyscraper consisted of a succession of warped wings developed on the layout of the logarithmic spiral. The helicoidal shape, works better than the others in splitting up the force of the wind in resistance, has a positive influence on the stability of the building and is the result of a strong design theory wondering about the power of invention, the power of geometry, the power of relationships among numbers, and finally the beauty of (deriving from) mathematics (in Architecture). -

Utopian Reality Russian History and Culture

Utopian Reality Russian History and Culture Editors-in-Chief Jeffrey P. Brooks The Johns Hopkins University Christina Lodder University of Kent VOLUME 14 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/rhc Utopian Reality Reconstructing Culture in Revolutionary Russia and Beyond Edited by Christina Lodder Maria Kokkori and Maria Mileeva LEIDEn • BOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: Staircase in the residential building for members of the Cheka (the Secret Police), Sverdlovsk (now Ekaterinburg), 1929–1936, designed by Ivan Antonov, Veniamin Sokolov and Arsenii Tumbasov. Photograph Richard Pare. © Richard Pare. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Utopian reality : reconstructing culture in revolutionary Russia and beyond / edited by Christina Lodder, Maria Kokkori and Maria Mileeva. pages cm. — (Russian history and culture, ISSN 1877-7791; volume 14) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-26320-8 (hardback : acid-free paper)—ISBN 978-90-04-26322-2 (e-book) 1. Soviet Union—Intellectual life—1917–1970. 2. Utopias—Soviet Union—History. 3. Utopias in literature. 4. Utopias in art. 5. Arts, Soviet—History. 6. Avant-garde (Aesthetics)—Soviet Union—History. 7. Cultural pluralism—Soviet Union—History. 8. Visual communication— Soviet Union—History. 9. Politics and culture—Soviet Union—History 10. Soviet Union— Politics and government—1917–1936. I. Lodder, Christina, 1948– II. Kokkori, Maria. III. Mileeva, Maria. DK266.4.U86 2013 947.084–dc23 2013034913 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. -

Laboratory of Reportage. Method

MAREK MILLER, PIOTR WOJCIECHOWSKI Laboratory of Reportage: An Outline of Research Issues Abstract The paper aims to present the outline of the research conducted by the Laboratory of Reportage. The Laboratory represents a place of journalistic experimentations and explorations. The experimentations consist of collective work on texts, multimedia narration, penetrating the area between journalism and literature. The research is directed towards scientific and artistic knowledge. The paper portrays both the history and the achievements of the Laboratory of Reportage and the method it employs. Keywords: reportage, documentary novel, polyphony, multimedia, oral history The Laboratory of Reportage operating within the Faculty of Journalism, Information and Book Studies of the University of Warsaw is a centre for research, experimentation and journalistic exploration as well as the place of practical didactic activities. We consider reportage as the fullest form of journalistic expression. Reportage, as a particularly open genre, embraces elements of interview, column and essay. It is close to non-fiction literature and film documentary. For a journalist willing to dig deeper into their knowledge it offers fundamental experience. That is why the Laboratory of Reportage was established. The field of the Laboratory’s experimentation and research covers: – collective work on text; – multimedia angle on material; – penetrating the area between journalism and creative writing, journalism and screenwriting, journalism and stage writing. However, reportage remains the base. The belief in the unique role of reportage within journalistic genres stems from our practice and experience. This article is an attempt to describe the latter. 18 MAREK MILLER, PIOTR WOJCIECHOWSKI I. Research, exploration and experimentation programme We do not hide that we have been long significantly inspired by the work of Juliusz Osterwa and Jerzy Grotowski. -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. INTRODUCTION “We were taught as children”—I was told by a seventy- year-old Pole—“that we Poles never harmed anyone. A partial abandonment of this morally comfortable position is very, very difficult for me.” —Helga Hirsch, a German journalist, in Polityka, 24 February 2001 HE COMPLEX and often acrimonious debate about the charac- ter and significance of the massacre of the Jewish population of T the small Polish town of Jedwabne in the summer of 1941—a debate provoked by the publication of Jan Gross’s Sa˛siedzi: Historia za- głady z˙ydowskiego miasteczka (Sejny, 2000) and its English translation Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland (Princeton, 2001)—is part of a much wider argument about the totali- tarian experience of Europe in the twentieth century. This controversy reflects the growing preoccupation with the issue of collective memory, which Henri Rousso has characterized as a central “value” reflecting the spirit of our time.1 One key element in the understanding of collec- tive memory is the “dark past” of nations—those aspects of the na- tional past that provoke shame, guilt, and regret; this past needs to be integrated into the national collective identity, which itself is continu- ally being reformulated.2 In this sense, memory has to be understood as a public discourse that helps to build group identity and is inevita- bly entangled in a relationship of mutual dependence with other iden- tity-building processes.