Introduction to the Skeletal System and the Axial Skeleton 155

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morfofunctional Structure of the Skull

N.L. Svintsytska V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 Ministry of Public Health of Ukraine Public Institution «Central Methodological Office for Higher Medical Education of MPH of Ukraine» Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukranian Medical Stomatological Academy» N.L. Svintsytska, V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 2 LBC 28.706 UDC 611.714/716 S 24 «Recommended by the Ministry of Health of Ukraine as textbook for English- speaking students of higher educational institutions of the MPH of Ukraine» (minutes of the meeting of the Commission for the organization of training and methodical literature for the persons enrolled in higher medical (pharmaceutical) educational establishments of postgraduate education MPH of Ukraine, from 02.06.2016 №2). Letter of the MPH of Ukraine of 11.07.2016 № 08.01-30/17321 Composed by: N.L. Svintsytska, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor V.H. Hryn, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor This textbook is intended for undergraduate, postgraduate students and continuing education of health care professionals in a variety of clinical disciplines (medicine, pediatrics, dentistry) as it includes the basic concepts of human anatomy of the skull in adults and newborns. Rewiewed by: O.M. Slobodian, Head of the Department of Anatomy, Topographic Anatomy and Operative Surgery of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Bukovinian State Medical University», Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor M.V. -

A Description of the Geological Context, Discrete Traits, and Linear Morphometrics of the Middle Pleistocene Hominin from Dali, Shaanxi Province, China

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 150:141–157 (2013) A Description of the Geological Context, Discrete Traits, and Linear Morphometrics of the Middle Pleistocene Hominin from Dali, Shaanxi Province, China Xinzhi Wu1 and Sheela Athreya2* 1Laboratory for Human Evolution, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, China 2Department of Anthropology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843 KEY WORDS Homo heidelbergensis; Homo erectus; Asia ABSTRACT In 1978, a nearly complete hominin Afro/European Middle Pleistocene Homo and align it fossil cranium was recovered from loess deposits at the with Asian H. erectus.Atthesametime,itdisplaysa site of Dali in Shaanxi Province, northwestern China. more derived morphology of the supraorbital torus and It was subsequently briefly described in both English supratoral sulcus and a thinner tympanic plate than and Chinese publications. Here we present a compre- H. erectus, a relatively long upper (lambda-inion) occi- hensive univariate and nonmetric description of the pital plane with a clear separation of inion and opis- specimen and provide comparisons with key Middle thocranion, and an absolute and relative increase in Pleistocene Homo erectus and non-erectus hominins brain size, all of which align it with African and Euro- from Eurasia and Africa. In both respects we find pean Middle Pleistocene Homo. Finally, traits such as affinities with Chinese H. erectus as well as African the form of the frontal keel and the relatively short, and European Middle Pleistocene hominins typically broad midface align Dali specifically with other referred to as Homo heidelbergensis.Specifically,the Chinese specimens from the Middle Pleistocene Dali specimen possesses a low cranial height, relatively and Late Pleistocene, including H. -

Topographical Anatomy and Morphometry of the Temporal Bone of the Macaque

Folia Morphol. Vol. 68, No. 1, pp. 13–22 Copyright © 2009 Via Medica O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E ISSN 0015–5659 www.fm.viamedica.pl Topographical anatomy and morphometry of the temporal bone of the macaque J. Wysocki 1Clinic of Otolaryngology and Rehabilitation, II Medical Faculty, Warsaw Medical University, Poland, Kajetany, Nadarzyn, Poland 2Laboratory of Clinical Anatomy of the Head and Neck, Institute of Physiology and Pathology of Hearing, Poland, Kajetany, Nadarzyn, Poland [Received 7 July 2008; Accepted 10 October 2008] Based on the dissections of 24 bones of 12 macaques (Macaca mulatta), a systematic anatomical description was made and measurements of the cho- sen size parameters of the temporal bone as well as the skull were taken. Although there is a small mastoid process, the general arrangement of the macaque’s temporal bone structures is very close to that which is observed in humans. The main differences are a different model of pneumatisation and the presence of subarcuate fossa, which possesses considerable dimensions. The main air space in the middle ear is the mesotympanum, but there are also additional air cells: the epitympanic recess containing the head of malleus and body of incus, the mastoid cavity, and several air spaces on the floor of the tympanic cavity. The vicinity of the carotid canal is also very well pneuma- tised and the walls of the canal are very thin. The semicircular canals are relatively small, very regular in shape, and characterized by almost the same dimensions. The bony walls of the labyrinth are relatively thin. -

Factors Influencing the Articular Eminence of the Temporomandibular Joint (Review)

EXPERIMENTAL AND THERAPEUTIC MEDICINE 22: 1084, 2021 Factors influencing the articular eminence of the temporomandibular joint (Review) MARIA JUSTINA ROXANA VÎRLAN1, DIANA LORETA PĂUN2, ELENA NICOLETA BORDEA3, ANGELO PELLEGRINI3, ARSENIE DAN SPÎNU4, ROXANA VICTORIA IVAȘCU5, VICTOR NIMIGEAN5 and VANDA ROXANA NIMIGEAN1 1Discipline of Oral Rehabilitation, Faculty of Dental Medicine; 2Discipline of Endocrinology, Faculty of Medicine; 3Department of Specific Disciplines, Faculty of Midwifery and Nursing;4 Discipline of Urology, ‘Dr Carol Davila’ Central Military Emergency University Hospital, Faculty of Medicine; 5Discipline of Anatomy, Faculty of Dental Medicine, ‘Carol Davila’ University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 020021 Bucharest, Romania Received April 28, 2021; Accepted May 28, 2021 DOI: 10.3892/etm.2021.10518 Abstract. The temporomandibular joint (TMJ), the most 4. Factors influencing the inclination of the articular eminence complex and evolved joint in humans, presents two articular 5. Biological sex surfaces: the condyle of the mandible and the articular eminence 6. Age (AE) of the temporal bone. AE is the anterior root of the zygo‑ 7. Edentulism matic process of the temporal bone and has an anterior and 8. Conclusions a posterior slope, the latter being also known as the articular surface. AE is utterly important in the biomechanics of the TMJ, as the mandibular condyle slides along the posterior slope 1. Introduction of the AE while the mandible moves. The aim of this review was to assess significant factors influencing the inclination of The temporomandibular joint (TMJ), the most complex and the AE, especially modifications caused by aging, biological evolved joint in humans, is defined by the paired joints that sex or edentulism. -

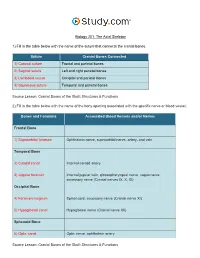

The Axial Skeleton Visual Worksheet

Biology 201: The Axial Skeleton 1) Fill in the table below with the name of the suture that connects the cranial bones. Suture Cranial Bones Connected 1) Coronal suture Frontal and parietal bones 2) Sagittal suture Left and right parietal bones 3) Lambdoid suture Occipital and parietal bones 4) Squamous suture Temporal and parietal bones Source Lesson: Cranial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 2) Fill in the table below with the name of the bony opening associated with the specific nerve or blood vessel. Bones and Foramina Associated Blood Vessels and/or Nerves Frontal Bone 1) Supraorbital foramen Ophthalmic nerve, supraorbital nerve, artery, and vein Temporal Bone 2) Carotid canal Internal carotid artery 3) Jugular foramen Internal jugular vein, glossopharyngeal nerve, vagus nerve, accessory nerve (Cranial nerves IX, X, XI) Occipital Bone 4) Foramen magnum Spinal cord, accessory nerve (Cranial nerve XI) 5) Hypoglossal canal Hypoglossal nerve (Cranial nerve XII) Sphenoid Bone 6) Optic canal Optic nerve, ophthalmic artery Source Lesson: Cranial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 3) Label the anterior view of the skull below with its correct feature. Frontal bone Palatine bone Ethmoid bone Nasal septum: Perpendicular plate of ethmoid bone Sphenoid bone Inferior orbital fissure Inferior nasal concha Maxilla Orbit Vomer bone Supraorbital margin Alveolar process of maxilla Middle nasal concha Inferior nasal concha Coronal suture Mandible Glabella Mental foramen Nasal bone Parietal bone Supraorbital foramen Orbital canal Temporal bone Lacrimal bone Orbit Alveolar process of mandible Superior orbital fissure Zygomatic bone Infraorbital foramen Source Lesson: Facial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 4) Label the right lateral view of the skull below with its correct feature. -

The Temporomandibular Joint: Pneumatic Temporal Cells Open Into the Articular and Extradural Spaces C

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Via Medica Journals Folia Morphol. Vol. 78, No. 3, pp. 630–636 DOI: 10.5603/FM.a2018.0111 O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E Copyright © 2019 Via Medica ISSN 0015–5659 journals.viamedica.pl The temporomandibular joint: pneumatic temporal cells open into the articular and extradural spaces C. Bichir, M.C. Rusu, A.D. Vrapciu, N. Măru “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Bucharest, Romania [Received: 1 October 2018; Accepted: 22 November 2018] The pneumatisation of the articular tubercle (PAT) of the temporal squama is a rare condition that modifies the barrier between the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) space and the middle cranial fossa. During a routine examination of the cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) files of patients who were scanned for dental medical purposes, we identified a case with multiple rare anatomic variations. First, the petrous apex was bilaterally pneumatised. Moreover, bilateral and multilocular PAT were observed, while on one side it was further found that the pneumatic cells were equally dehiscent towards the extradural space and the superior joint space. To the best of our knowledge, such dehiscence has not pre- viously been reported. The two temporomastoid pneumatisations were extended with occipital pneumatisations of the lateral masses and occipital condyles, the latter being an extremely rare evidence. The internal dehiscence of the mandibular canal in the right ramus of the mandible was also noted. Additionally, double mental foramen and impacted third molars were found on the left side. -

Axial Skeleton 214 7.7 Development of the Axial Skeleton 214

SKELETAL SYSTEM OUTLINE 7.1 Skull 175 7.1a Views of the Skull and Landmark Features 176 7.1b Sutures 183 7.1c Bones of the Cranium 185 7 7.1d Bones of the Face 194 7.1e Nasal Complex 198 7.1f Paranasal Sinuses 199 7.1g Orbital Complex 200 Axial 7.1h Bones Associated with the Skull 201 7.2 Sex Differences in the Skull 201 7.3 Aging of the Skull 201 Skeleton 7.4 Vertebral Column 204 7.4a Divisions of the Vertebral Column 204 7.4b Spinal Curvatures 205 7.4c Vertebral Anatomy 206 7.5 Thoracic Cage 212 7.5a Sternum 213 7.5b Ribs 213 7.6 Aging of the Axial Skeleton 214 7.7 Development of the Axial Skeleton 214 MODULE 5: SKELETAL SYSTEM mck78097_ch07_173-219.indd 173 2/14/11 4:58 PM 174 Chapter Seven Axial Skeleton he bones of the skeleton form an internal framework to support The skeletal system is divided into two parts: the axial skele- T soft tissues, protect vital organs, bear the body’s weight, and ton and the appendicular skeleton. The axial skeleton is composed help us move. Without a bony skeleton, we would collapse into a of the bones along the central axis of the body, which we com- formless mass. Typically, there are 206 bones in an adult skeleton, monly divide into three regions—the skull, the vertebral column, although this number varies in some individuals. A larger number of and the thoracic cage (figure 7.1). The appendicular skeleton bones appear to be present at birth, but the total number decreases consists of the bones of the appendages (upper and lower limbs), with growth and maturity as some separate bones fuse. -

The Temporomandibular Joint: Pneumatic Temporal Cells Open Into the Articular and Extradural Spaces C

Folia Morphol. Vol. 78, No. 3, pp. 630–636 DOI: 10.5603/FM.a2018.0111 O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E Copyright © 2019 Via Medica ISSN 0015–5659 journals.viamedica.pl The temporomandibular joint: pneumatic temporal cells open into the articular and extradural spaces C. Bichir, M.C. Rusu, A.D. Vrapciu, N. Măru “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Bucharest, Romania [Received: 1 October 2018; Accepted: 22 November 2018] The pneumatisation of the articular tubercle (PAT) of the temporal squama is a rare condition that modifies the barrier between the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) space and the middle cranial fossa. During a routine examination of the cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) files of patients who were scanned for dental medical purposes, we identified a case with multiple rare anatomic variations. First, the petrous apex was bilaterally pneumatised. Moreover, bilateral and multilocular PAT were observed, while on one side it was further found that the pneumatic cells were equally dehiscent towards the extradural space and the superior joint space. To the best of our knowledge, such dehiscence has not pre- viously been reported. The two temporomastoid pneumatisations were extended with occipital pneumatisations of the lateral masses and occipital condyles, the latter being an extremely rare evidence. The internal dehiscence of the mandibular canal in the right ramus of the mandible was also noted. Additionally, double mental foramen and impacted third molars were found on the left side. Such multilocular PAT represents a low-resistance pathway for the bidirectional spread of fluids through the roof of the TMJ. -

A Functional Analysis of the Temporomandibular Joint in Homosapiens Sapiens and Homo Sapiens Neanderthalensis

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 6-1978 A Functional Analysis of the Temporomandibular Joint in Homosapiens sapiens and Homo sapiens neanderthalensis Janice Lynn Foxworthy University of Tennessee, Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Foxworthy, Janice Lynn, "A Functional Analysis of the Temporomandibular Joint in Homosapiens sapiens and Homo sapiens neanderthalensis. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1978. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4249 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Janice Lynn Foxworthy entitled "A Functional Analysis of the Temporomandibular Joint in Homosapiens sapiens and Homo sapiens neanderthalensis." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Anthropology. Fred H. Smith, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Richard L. Jantz, William M. Bass Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate CoWlcil: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Janice Lynn Foxworthy entitled "A Functional Analysis of the Tempo�omandibular Joint in Homo sapiens sapiens and Homo sapiens neanderthalensis." I recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Anthropology. -

Surgical Anatomy of the Temporal Bone Gülay Açar and Aynur Emine Çiçekcibaşı

Chapter Surgical Anatomy of the Temporal Bone Gülay Açar and Aynur Emine Çiçekcibaşı Abstract Numerous neurological lesions and tumors of the paranasal sinuses and oral cavity may spread into the middle and posterior cranial fossae through the ana- tomical apertures. For the appropriate management of these pathologies, many extensive surgical approaches with a comprehensive overview of the anatomical landmarks are required from the maxillofacial surgery’s point of view. The surgical significance lies in the fact that iatrogenic injury to the petrous segment of the tem- poral bone including the carotid artery, sigmoid sinus, and internal jugular vein, can lead to surgical morbidity and postoperative pseudoaneurysm, vasospasm, or carotid-cavernous fistula. To simplify understanding complex anatomy of the temporal bone, we aimed to review the surgical anatomy of the temporal bone focusing on the associations between the surface landmarks and inner structures. Also, breaking down an intricate bony structure into smaller parts by compart- mental approach could ease a deep concentration and navigation. To identify the anatomic architecture of the temporal bone by using reference points, lines and compartments can be used to supplement anatomy knowledge of maxillofacial surgeons and may improve confidence by surgical trainees. Especially, this system- atic method may provide an easier way to teach and learn surgical spatial structure of the petrous pyramid in clinical applications. Keywords: maxillofacial surgery, segmentation, surface landmarks, surgical anatomy, temporal bone 1. Introduction The temporal bone is a dense complex bone that constitutes the lower lateral aspect of the skull and has complex anatomy because of the three-dimensional relationships between neurovascular structures. -

Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)

Regions of the Head 9. Oral Cavity & Perioral Regions Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) Zygomatic process of temporal bone Articular tubercle Mandibular Petrotympanic fossa of TMJ fissure Postglenoid tubercle Styloid process External acoustic meatus Mastoid process (auditory canal) Atlanto- occipital joint Fig. 9.27 Mandibular fossa of the TMJ tubercle. Unlike other articular surfaces, the mandibular fossa is cov- Inferior view of skull base. The head (condyle) of the mandible artic- ered by fi brocartilage, not hyaline cartilage. As a result, it is not as ulates with the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone via an articu- clearly delineated on the skull (compare to the atlanto-occipital joints). lar disk. The mandibular fossa is a depression in the squamous part of The external auditory canal lies just posterior to the mandibular fossa. the temporal bone, bounded by an articular tubercle and a postglenoid Trauma to the mandible may damage the auditory canal. Head (condyle) of mandible Pterygoid Joint fovea capsule Neck of Coronoid mandible Lateral process ligament Neck of mandible Lingula Mandibular Stylomandibular foramen ligament Mylohyoid groove AB Fig. 9.28 Head of the mandible in the TMJ Fig. 9.29 Ligaments of the lateral TMJ A Anterior view. B Posterior view. The head (condyle) of the mandible is Left lateral view. The TMJ is surrounded by a relatively lax capsule that markedly smaller than the mandibular fossa and has a cylindrical shape. permits physiological dislocation during jaw opening. The joint is stabi- Both factors increase the mobility of the mandibular head, allowing lized by three ligaments: lateral, stylomandibular, and sphenomandib- rotational movements about a vertical axis. -

Anatomy Lab: the Skeletal System Part I: Vertebrae and Thoracic Cage

ANA Lab: Bone 1 Anatomy Lab: The skeletal system Part I: Vertebrae and Thoracic cage Spine (Vertebrae) Body Vertebral arch Vertebral canal Pedicle Lamina Spinous process Transverse process Sup. articular facets Inf. articular facets Sup. vertebral notch Inf. vertebral notch Intervertebral foramen Cervical vertebrae: 7 Typical (C3-C6) Transverse foramen C1, Atlas C2, Axis: dens C7 Thoracic vertebrae: 12 Typical (T2-T10) T1 T11, 12 Lumbar vertebrae: 5 Typical (L1-4) Sacrum: 5 Ala Anterior sacral foramina Posterior sacral foramina Sacral canal ANA Lab: Bone 2 Sacral hiatus promontory median sacral crest intermediate crest lateral crest Coccyx Horns Transverse process Thoracic cages Ribs: 12 pairs Typical ribs (R3-R10): Head, 2 facets intermediate crest neck tubercle angle costal cartilage costal groove R1 R2 R11,12 Sternum Manubrium of sternum Clavicular notch for sternoclavicular joint body xiphoid process ANA Lab: Bone 3 Part II: Skull and Facial skeleton Skull Cranial skeleton, Calvaria (neurocranium) Facial skeleton (viscerocranium) Overview: identify the margin of each bone Cranial skeleton 1. Lateral view Frontal Temporal Parietal Occipital 2. Cranial base midline: Ethmoid, Sphenoid, Occipital bilateral: Temporal Viscerocranium 1. Anterior view Ethmoid, Vomer, Mandible Maxilla, Zygoma, Nasal, Lacrimal, Inferior nasal chonae, Palatine 2. Inferior view Palatine, Maxilla, Zygoma Sutures: external view vs. internal view Coronal suture Sagittal suture Lambdoid suture External appearance of skull Posterior view external occipital protuberance