Structural Irregularities Within the English Language: Implications for Teaching and Learning in Second Language Situations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Workbook B- 1

MICHAEL BEND ABeCeDarian STUDENT WORKBOOK B- 1 FA L L 2 0 0 6 © ABECEDARIAN COMPANY JULY 2006. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. a•be•ce•dar•i•an n. (ay-bee-cee-dair-ee-an) 1. One who teaches or studies the alphabet. 2. One who is just learning; a beginner. a•be•ce•dar•i•an adj. 1. Having to do with the alphabet. 2. Being arranged alphabetically. 3. Elementary or rudimentary. [Middle English, from Medieval Latin abecedarium, alphabet, from Late Latin abecedarius, alphabetical : from the names of the letters A B C D + -arius, -ary.] from The American Heritage Dictionary, Third Edition Copyright © 2000-2006 ABeCeDarian Company Visit us at www.abcdrp.com June 12,2006 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. 2 DATE ASSIGNMENT COPYRIGHT ©ABECEDARIAN COMPANY 2004-2006 3 DATE ASSIGNMENT 4 oa o-e o ow oe ough COPYRIGHT ©ABECEDARIAN COMPANY 2004-2006 1 Unit One 5 Unit 1 Sorting words with oa o-e o ow oe ough Read the words below and sort them using the following record sheet. Remember, always say the sound before you write it. 1. b oa t 5. g r ow 9. h o m e 2. sh ow 6. r o p e 10. g o 3. t oe 7. l oa f 11. n o t e 4. m o s t 8. c oa t 12. th ough 1 2 3 4 5 6 oa o-e o ow oe ough 6 Unit 1 I Spy with oa o-e o ow oe ough Underline oa, o-e, o, ow, oe, or ough in the words below and read them. -

Influences on the Development of Early Modern English

Influences on the Development of Early Modern English Kyli Larson Wright This article covers the basic social, historical, and linguistic influences that have transformed the English language. Research first describes components of Early Modern English, then discusses how certain factors have altered the lexicon, phonology, and other components. Though there are many factors that have shaped English to what it is today, this article only discusses major factors in simple and straightforward terms. 72 Introduction The history of the English language is long and complicated. Our language has shifted, expanded, and has eventually transformed into the lingua franca of the modern world. During the Early Modern English period, from 1500 to 1700, countless factors influenced the development of English, transforming it into the language we recognize today. While the history of this language is complex, the purpose of this article is to determine and map out the major historical, social, and linguistic influences. Also, this article helps to explain the reasons for their influence through some examples and evidence of writings from the Early Modern period. Historical Factors One preliminary historical event that majorly influenced the development of the language was the establishment of the print- ing press. Created in 1476 by William Caxton at Westminster, London, the printing press revolutionized the current language form by creating a means for language maintenance, which helped English gravitate toward a general standard. Manuscripts could be reproduced quicker than ever before, and would be identical copies. Because of the printing press spelling variation would eventually decrease (it was fixed by 1650), especially in re- ligious and literary texts. -

Some English Words Illustrating the Great Vowel Shift. Ca. 1400 Ca. 1500 Ca. 1600 Present 'Bite' Bi:Tə Bəit Bəit

Some English words illustrating the Great Vowel Shift. ca. 1400 ca. 1500 ca. 1600 present ‘bite’ bi:tә bәit bәit baIt ‘beet’ be:t bi:t bi:t bi:t ‘beat’ bɛ:tә be:t be:t ~ bi:t bi:t ‘abate’ aba:tә aba:t > abɛ:t әbe:t әbeIt ‘boat’ bɔ:t bo:t bo:t boUt ‘boot’ bo:t bu:t bu:t bu:t ‘about’ abu:tә abәut әbәut әbaUt Note that, while Chaucer’s pronunciation of the long vowels was quite different from ours, Shakespeare’s pronunciation was similar enough to ours that with a little practice we would probably understand his plays even in the original pronuncia- tion—at least no worse than we do in our own pronunciation! This was mostly an unconditioned change; almost all the words that appear to have es- caped it either no longer had long vowels at the time the change occurred or else entered the language later. However, there was one restriction: /u:/ was not diphthongized when followed immedi- ately by a labial consonant. The original pronunciation of the vowel survives without change in coop, cooper, droop, loop, stoop, troop, and tomb; in room it survives in the speech of some, while others have shortened the vowel to /U/; the vowel has been shortened and unrounded in sup, dove (the bird), shove, crumb, plum, scum, and thumb. This multiple split of long u-vowels is the most signifi- cant IRregularity in the phonological development of English; see the handout on Modern English sound changes for further discussion. -

The English Language

The English Language Version 5.0 Eala ðu lareow, tæce me sum ðing. [Aelfric, Grammar] Prof. Dr. Russell Block University of Applied Sciences - München Department 13 – General Studies Winter Semester 2008 © 2008 by Russell Block Um eine gute Note in der Klausur zu erzielen genügt es nicht, dieses Skript zu lesen. Sie müssen auch die “Show” sehen! Dieses Skript ist der Entwurf eines Buches: The English Language – A Guide for Inquisitive Students. Nur der Stoff, der in der Vorlesung behandelt wird, ist prüfungsrelevant. Unit 1: Language as a system ................................................8 1 Introduction ...................................... ...................8 2 A simple example of structure ..................... ......................8 Unit 2: The English sound system ...........................................10 3 Introduction..................................... ...................10 4 Standard dialects ................................ ....................10 5 The major differences between German and English . ......................10 5.1 The consonants ................................. ..............10 5.2 Overview of the English consonants . ..................10 5.3 Tense vs. lax .................................. ...............11 5.4 The final devoicing rule ....................... .................12 5.5 The “th”-sounds ................................ ..............12 5.6 The “sh”-sound .................................. ............. 12 5.7 The voiced sounds / Z/ and / dZ / ...................................12 5.8 The -

Standardization in Early English Orthography

Standardization in Early English Orthography Over thirty years ago Fred Brengelman pointed out that since at least 1909 and George Krapp’s Modern English: Its Growth and Present Use, it was widely assumed that English printers played the major role in the standardization of English spelling.1 Brengelman demonstrated convincingly that the role of the printers was at best minimal and that much more important was the work done in the late 16th and 17th centuries by early English orthoepists and spelling reformers – people like Richard Mulcaster, John Cheke, Thomas Smith, John Hart, William Bullokar, Alexander Gil, and Richard Hodges.2 Brengelman’s argument is completely convincing, but it concentrates on developments rather late in the history of English orthography – developments that were external to the system itself and basically top-down. It necessarily ignores the extent to which much standardization occurred naturally and internally during the 11th through 16th centuries. This early standardization was not a top-down process, but rather bottom-up, arising from the communication acts of individual spellers and their readers – many small actions by many agents. In what follows I argue that English orthography is an evolving system, and that this evolution produced a degree of standardization upon which the 16th and 17th century orthoepists could base their work, work that not only further rationalized and standardized our orthography, as Brengelman has shown, but also marked the beginning of the essentially top-down system that we have today. English Orthography as an Evolving Complex System. English orthography is not just an evolving system; it is an evolving complex system – adaptive, self-regulating, and self-organizing. -

A Corpus·Based Investigation of Xhosa English In

A CORPUS·BASED INVESTIGATION OF XHOSA ENGLISH IN THE CLASSROOM SETTING A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS of RHODES UNIVERSITY by CANDICE LEE PLATT January 2004 Supervisor: Professor V.A de K1erk ABSTRACT This study is an investigation of Xhosa English as used by teachers in the Grahamstown area of the Eastern Cape. The aims of the study were firstly, to compile a 20 000 word mini-corpus of the spoken English of Xhosa mother tongue teachers in Grahamstown, and to use this data to describe the characteristics of Xhosa English used in the classroom context; and secondly, to assess the usefulness of a corpus-based approach to a study of this nature. The English of five Xhosa mother-tongue teachers was investigated. These teachers were recorded while teaching in English and the data was then transcribed for analysis. The data was analysed using Wordsmith Tools to investigate patterns in the teachers' language. Grammatical, lexical and discourse patterns were explored based on the findings of other researchers' investigations of Black South African English and Xhosa English. In general, many of the patterns reported in the literature were found in the data, but to a lesser extent than reported in literature which gave quantitative information. Some features not described elsewhere were also found . The corpus-based approach was found to be useful within the limits of pattern matching. 1I TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1.1 CORPORA 1 1.2 BLACK SOUTH -

Assistive Technology Resources for Children and Adults with Disabilities

Assistive Technology Resources for Children and Adults with Disabilities June / July, 2012 ClosingVOLUME 31 - NUMBER 2 The Gap The Importance of Play for Kids with Disabilities Building Independence with Picture Directions I Just Bought the New iPAD… Now what??? Physical Access and Training to Use the iPad Help for THOSE Classrooms DISKoveries 30th Annual Closing The Gap Conference Details Permit No. 166 No. Permit Hutchinson, MN 55350 MN Hutchinson, U.S POSTAGE PAID POSTAGE U.S www.closingthegap.com AUTO PRSRT STD PRSRT STAFF Dolores Hagen ...... PUBLISHER contents june / july, 2012 Budd Hagen ..................EDITOR volume 31 | number 2 Connie Kneip .................................. VICE PRESIDENT / GENERAL MANAGER 4 The Importance of Play for Kids 14 Physical Access and Training to Megan Turek ........... MANAGING with Disabilities Use the iPad EDITOR / By Sue Redepenning and By Patricia Bahr and Katie Duff SALES MANAGER Jennifer Mundl Jan Latzke ...... SUBSCRIPTIONS Sarah Anderson .............................. ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT Becky Hagen .....................SALES Marc Hagen ............................WEB DEVELOPMENT SUBSCRIPTIONS $39 per year in the United States. $55 per year to Canada and Mexico (air mail.) All subscriptions from outside 17 Help for THOSE Classrooms the United States must be accom- panied by a money order or a check By Julie Rick drawn on a U.S. bank and payable in U.S. funds. Purchase orders are accepted from schools or institutions in the United States. 8 Building Independence with PUBLICATION INFORMATION Picture Directions Closing The Gap (ISSN: 0886-1935) is By Pat Crissey published bi-monthly in February, April, June, August, October and December. Single copies are available for $7.00 (postpaid) for U.S. -

ELL101: Intro to Linguistics Week 1 Phonetics &

ELL101: Intro to Linguistics Week 1 Phonetics & IPA Tomonori Nagano <[email protected]> Education and Language Acquisition Dept. LaGuardia Community College August 16, 2017 . Tomonori Nagano <[email protected]> Edu&Lang Acq. Dept., LaGuardia CC 1/41 Fields of linguistics • Week 1-2: Phonetics (physical sound properties) • Week 2-3: Phonology (speech sound rules) • Week 4: Morphology (word parts) • Week 5-6: Syntax (structure) • Week 7-8: Semantics (meaning) • Week 7-8: Pragmatics (conversation & convention) • Week 9: First & Second language acquisition • Week 10-12: Historical linguistics (history of language) • Week 10-12: Socio-linguistics (language in society) • Week 10-12: Neuro-linguistics (the brain and language) • Week 10-12: Computational linguistics (computer and language) • Week 10-12: Evolutional linguistics (how language evolved in human history) . Tomonori Nagano <[email protected]> Edu&Lang Acq. Dept., LaGuardia CC 2/41 Overview Phonetics Phonetics is a study of the characteristics of the speech sound (p.30; Yule (2010)) Branches of phonetics • Articulatory phonetics • how speech sounds are made • Acoustic phonetics • physical properties of speech sounds • Auditory phonetics • how speech sounds are perceived • See some examples of phonetics research: • Speech visualization (acoustic / auditory phonetics) • ”McGurk effect” (auditory phonetics) . Tomonori Nagano <[email protected]> Edu&Lang Acq. Dept., LaGuardia CC 3/41 Acoustic phonetics (example) • The speech wave (spectorogram) of ”[a] (as in above), [ɛ] (as in bed), and [ɪ] (as in bit)” 5000 ) z H ( y c n e u q e r F 0 0 . .0.3799. Time (s) . Tomonori Nagano <[email protected]> Edu&Lang Acq. Dept., LaGuardia CC 4/41 Acoustic phonetics (example) • The speech wave (spectorogram) of ”Was that a good movie you saw?” 5000 ) z H ( y c n e u q e r F 0 0 2.926 Time (s) . -

Natural Phonetic Tendencies and Social Meaning: Exploring the Allophonic Raising Split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly

This is a repository copy of Natural phonetic tendencies and social meaning: Exploring the allophonic raising split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/133952/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Moore, E.F. and Carter, P. (2018) Natural phonetic tendencies and social meaning: Exploring the allophonic raising split of PRICE and MOUTH on the Isles of Scilly. Language Variation and Change, 30 (3). pp. 337-360. ISSN 0954-3945 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394518000157 This article has been published in a revised form in Language Variation and Change [https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394518000157]. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © Cambridge University Press. Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Title: Natural phonetic tendencies -

Strand 1: Foundational Language Skills

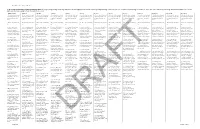

English Language Arts and Reading (1) Developing and Sustaining Foundational Language Skills: Listening, Speaking, Reading, and Writing. Students develop oral language and word structure knowledge through phonological awareness, print concepts, phonics and, morphology to communicate, decode and encode. Students apply knowledge and relationships found in the structures, origins, and contextual meanings of words. The student is expected to: Kindergarten Grade 1 Grade 2 Grade 3 Grade 4 Grade 5 Grade 6 Grade 7 Grade 8 English I English II English III English IV (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and (A) self-select text and read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for read independently for a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of a sustained period of time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; time; (B) develop -

A Study of Idiom Translation Strategies Between English and Chinese

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 3, No. 9, pp. 1691-1697, September 2013 © 2013 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.9.1691-1697 A Study of Idiom Translation Strategies between English and Chinese Lanchun Wang School of Foreign Languages, Qiongzhou University, Sanya 572022, China Shuo Wang School of Foreign Languages, Qiongzhou University, Sanya 572022, China Abstract—This paper, focusing on idiom translation methods and principles between English and Chinese, with the statement of different idiom definitions and the analysis of idiom characteristics and culture differences, studies the strategies on idiom translation, what kind of method should be used and what kind of principle should be followed as to get better idiom translations. Index Terms— idiom, translation, strategy, principle I. DEFINITIONS OF IDIOMS AND THEIR FUNCTIONS Idiom is a language in the formation of the unique and fixed expressions in the using process. As a language form, idioms has its own characteristic and patterns and used in high frequency whether in written language or oral language because idioms can convey a host of language and cultural information when people chat to each other. In some senses, idioms are the reflection of the environment, life, historical culture of the native speakers and are closely associated with their inner most spirit and feelings. They are commonly used in all types of languages, informal and formal. That is why the extent to which a person familiarizes himself with idioms is a mark of his or her command of language. Both English and Chinese are abundant in idioms. -

L Vocalisation As a Natural Phenomenon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Essex Research Repository L Vocalisation as a Natural Phenomenon Wyn Johnson and David Britain Essex University [email protected] [email protected] 1. Introduction The sound /l/ is generally characterised in the literature as a coronal lateral approximant. This standard description holds that the sounds involves contact between the tip of the tongue and the alveolar ridge, but instead of the air being blocked at the sides of the tongue, it is also allowed to pass down the sides. In many (but not all) dialects of English /l/ has two allophones – clear /l/ ([l]), roughly as described, and dark, or velarised, /l/ ([…]) involving a secondary articulation – the retraction of the back of the tongue towards the velum. In dialects which exhibit this allophony, the clear /l/ occurs in syllable onsets and the dark /l/ in syllable rhymes (leaf [li˘f] vs. feel [fi˘…] and table [te˘b…]). The focus of this paper is the phenomenon of l-vocalisation, that is to say the vocalisation of dark /l/ in syllable rhymes 1. feel [fi˘w] table [te˘bu] but leaf [li˘f] 1 This process is widespread in the varieties of English spoken in the South-Eastern part of Britain (Bower 1973; Hardcastle & Barry 1989; Hudson and Holloway 1977; Meuter 2002, Przedlacka 2001; Spero 1996; Tollfree 1999, Trudgill 1986; Wells 1982) (indeed, it appears to be categorical in some varieties there) and which extends to many other dialects including American English (Ash 1982; Hubbell 1950; Pederson 2001); Australian English (Borowsky 2001, Borowsky and Horvath 1997, Horvath and Horvath 1997, 2001, 2002), New Zealand English (Bauer 1986, 1994; Horvath and Horvath 2001, 2002) and Falkland Island English (Sudbury 2001).