Landscape and Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What's up with Those Sprinklers, Anyway? Sesses Their Fluency in English

Great Aloha Fun Run needs page.6 Pl1 Kapi'olani Community College Vol. 32 Issue 17 February 2, 1999 Faculty protests. loss ofparking campus. This provides valuable ex first come-first serve basis, she said, Jimmy Chow perience for them when they enter adding, the 'Olapa lot was chosen Staff Writer the job market. because it was often the last to fill. Some of you may have noticed The Ka 'Ikena Dining Room She also mentioned that more of the the bright orange chain hanging on handles roughly 50 customers daily, existing stalls would be available to the wall in the parking lot in front of 80 percent of which come from off the staff if it were not for students the 'Olapa building. Alongside the campus. In the past, business has who risk ticketing and park where chain are two signs that clearly state been good. However, a lot of cus they should not. Kinningham went "No parking between the hours of tomers have been lost due to a lack on to ask that the faculty " ... be pa 10:30 a.m. and 2 p.m. Violators may of parking. When there are no cus tient," and perhaps "come a little be towed." tomers, there is no work for the stu earlier." These 15 parking spaces are re dents, he said. Dirk Soma invites any faculty photo by Moriso Teraoka served for the patrons of the Ka As for Kinningham, she wanted member who may have additional Alternative rock band Way Cool Jr. entertains the student body in the 'Ikena Dining Room, the Tamarind to remind everyone that KCC's park questions or comments to contact Central Mall. -

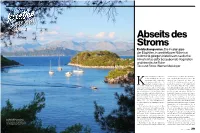

Abseits Des Stroms Entdeckungsreise

KROATIEN SPEZIAL • ELAPHITEN Abseits des Stroms Entdeckungsreise. Die Inselgruppe der Elaphiten, in unmittelbarer Nähe von Dubrovnik gelegen, bietet kaum nautische Infrastruktur, dafür bezaubernde Vegetation und himmlische Ruhe Text und Fotos: Werner Meisinger aee und Kuchen in Korčula. scheidenen Infrastruktur für den Touris- In den Lokalen auf der Fes- mus. Auch für den Bootstourismus. Be- tungsmauer gibt es attraktive scheiden im Vergleich zu dem, was Gelegenheiten dafür. Die Cafés nörd lich der Elaphiten geboten wird. In und Bars sind auf jeden Ge- den Buchten und Häfen Mitteldalmatiens Kschmack eingestellt. Neben der klassischen – von Šolta, Brač, Hvar, Korčula – stecken Cappuccino-Croissant-Palette serviert man die Yachten dicht an dicht, an die Bojen der auch Smoothies und Fruchttörtchen, haus- eigens angelegten Felder werden sie gele- gemachte Säfte und schicke Müslis. Alles gentlich paarweise verordnet. Die Marinas garniert mit Blick aufs Meer. Da bleibt der und Häfen begehren fantastische Gagen Gast im Schatten der Pinien gern eine Zeit für geringste bis gar keine Dienstleis- lang sitzen und beobachtet das Treiben auf tungen. Auch rund Mljet ist noch eine dem Wasser. Während eines solchen Früh- Menge los. Von dort Richtung Osten und stücks kann man mehr Schie vorüber Süden herrscht aber radikale Verkehrsver- gondeln sehen als in den Elaphiten in ei- dünnung. In den Elaphiten gibt es keine ner Woche. Marina und keine bewirtschafteten Bojen. Die Elaphiten sind der südöstliche Fort- Die nächstgelegene Charterbasis ist Dubrov- satz der berühmten Sehnsuchtsdestinati- nik, wo nicht gerade die stärksten Flotten onen vor der kroatischen Küste, zu denen der Bootsverleih-Industrie stationiert sind. es Jahr für Jahr an die vier Millionen Besu- Die Elaphiten liegen also abseits des Stroms, cher zieht. -

Turizam Na Hrvatskim I Njemačkim Otocima

Turizam na hrvatskim i njemačkim otocima Tolj, Andro Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zadar / Sveučilište u Zadru Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:162:985822 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-25 Repository / Repozitorij: University of Zadar Institutional Repository of evaluation works Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za turizam i komunikacijske znanosti Jednopredmetni preddiplomski studij Kulture i turizma Andro Tolj Turizam na hrvatskim i njemačkim otocima Završni rad Zadar, 2016. Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za turizam i komunikacijske znanosti Jednopredmetni preddiplomski studij Kulture i turizma Turizam na hrvatskim i njemačkim otocima Završni rad Student/ica: Mentor/ica: Andro Tolj Mr. sc., Tomislav Krpan Zadar, 2016. Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Ja, Andro Tolj, ovime izjavljujem da je moj završni rad pod naslovom Turizam na hrvatskim i njemačkim otocima rezultat mojega vlastitog rada, da se temelji na mojim istraživanjima te da se oslanja na izvore i radove navedene u bilješkama i popisu literature. Ni jedan dio mojega rada nije napisan na nedopušten način, odnosno nije prepisan iz necitiranih radova i ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. Izjavljujem da ni jedan dio ovoga rada nije iskorišten u kojem drugom radu pri bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj, obrazovnoj ili inoj ustanovi. Sadržaj mojega rada u potpunosti odgovara sadržaju obranjenoga i nakon obrane uređenoga -

Hrvatski Jadranski Otoci, Otočići I Hridi

Hrvatski jadranski otoci, otočići i hridi Sika od Mondefusta, Palagruţa Mjerenja obale istoĉnog Jadrana imaju povijest; svi autori navode prvi cjelovitiji popis otoka kontraadmirala austougarske mornarice Sobieczkog (Pula, 1911.). Glavni suvremeni izvor dugo je bio odliĉni i dosad još uvijek najsustavniji pregled za cijelu jugoslavensku obalu iz godine 1955. [1955].1 Na osnovi istraţivanja skupine autora, koji su ponovo izmjerili opsege i površine hrvatskih otoka i otoĉića većih od 0,01 km2 [2004],2 u Ministarstvu mora, prometa i infrastrukture je zatim 2007. godine objavljena opseţna nova graĊa, koju sad moramo smatrati referentnom [2007].3 No, i taj pregled je manjkav, ponajprije stoga jer je namijenjen specifiĉnom administrativnom korištenju, a ne »statistici«. Drugi problem svih novijih popisa, barem onih objavljenih, jest taj da ne navode sve najmanje otoĉiće i hridi, iako ulaze u konaĉne brojke.4 Brojka 1244, koja je sada najĉešće u optjecaju, uopće nije dokumentirana.5 Osnovni izvor za naš popis je, dakle, [2007], i u graniĉnim primjerima [2004]. U napomenama ispod tablica navedena su odstupanja od tog izvora. U sljedećem koraku pregled je dopunjen podacima iz [1955], opet s obrazloţenjima ispod crte. U trećem koraku ukljuĉeno je još nekoliko dodatnih podataka s obrazloţenjem.6 1 Ante Irić, Razvedenost obale i otoka Jugoslavije. Hidrografski institut JRM, Split, 1955. 2 T. Duplanĉić Leder, T. Ujević, M. Ĉala, Coastline lengths and areas of islands in the Croatian part of the Adriatic sea determined from the topographic maps at the scale of 1:25.000. Geoadria, 9/1, Zadar, 2004. 3 Republika Hrvatska, Ministarstvo mora, prometa i infrastrukture, Drţavni program zaštite i korištenja malih, povremeno nastanjenih i nenastanjenih otoka i okolnog mora (nacrt prijedloga), Zagreb, 30.8.2007.; objavljeno na internetskoj stranici Ministarstva. -

Arbiter, July 13 Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 7-13-2005 Arbiter, July 13 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. Cleveland ''The~rrior" Corder Peg Blake resigns, I Wheeler to continue t. as interim Vpi BY RANDALL P05T News Editor Cut locks and computer 'accessorles were strewn abo~t th~ VIllage aparlments computer lab after a break-In on June 20. PHofo BY RANDAll. POSTmlE ARBITER PHaro CDUlmSY UNIVERSITY RELATIONS many milestones, including the completion of a 40-child addi- Computers stolen from Village tion to the Children's Center, de- velopment of an expanded New Student Orientation Program, co-chairing with BSU Provost Sona Andrews on the Preshman apartments -lab, no arrests made Success Task Force, and cham- pioning the $8.5 million Student BY 5ARA BAHN50N the 24-hour lab was closed..The lockedat all times. can be entered ServicesBuildingand a $12.5mil- ASSistant News Editor BSUPolice Department believes through the use of a traditional lion Student Health Wellness and that four all-in-one computers, to keyor a student 10 keycard. Counseling facility. Four computers were stolen which the computer unit and the Video surveillance of the com- "She.will certainly be missed from the Boise State University monitor are attached, were stolen puter lab was in use at the time and was a tireless advocate for the Villageapartments' computerlab by the man follo~ing thedepar- ." of-the theft, but images gathered shideiftii IoZiiiik..:Siiiif"':)' V . -

IATSE and Labor Movement News

FIRST QUARTER, 2012 NUMBER 635 FEATURES Report of the 10 General Executive Board January 30 - February 3, 2012, Atlanta, Georgia Work Connects Us All AFL-CIO Launches New 77 Campaign, New Website New IATSE-PAC Contest 79 for the “Stand up, Fight Back” Campaign INTERNATIONAL ALLIANCE OF THEATRICAL STAGE EMPLOYEES, MOVING PICTURE TECHNICIANS, ARTISTS AND ALLIED CRAFTS OF THE UNITED STATES, ITS TERRITORIES AND CANADA, AFL-CIO, CLC EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Matthew D. Loeb James B. Wood International President General Secretary–Treasurer Thomas C. Short Michael W. Proscia International General Secretary– President Emeritus Treasurer Emeritus Edward C. Powell International Vice President Emeritus Timothy F. Magee Brian J. Lawlor 1st Vice President 7th Vice President 900 Pallister Ave. 1430 Broadway, 20th Floor Detroit, MI 48202 New York, NY 10018 DEPARTMENTS Michael Barnes Michael F. Miller, Jr. 2nd Vice President 8th Vice President 2401 South Swanson Street 10045 Riverside Drive Philadelphia, PA 19148 Toluca Lake, CA 91602 4 President’s 74 Local News & Views J. Walter Cahill John T. Beckman, Jr. 3rd Vice President 9th Vice President Newsletter 5010 Rugby Avenue 1611 S. Broadway, #110 80 On Location Bethesda, MD 20814 St Louis, MO 63104 Thom Davis Daniel DiTolla 5 General Secretary- 4th Vice President 10th Vice President 2520 West Olive Avenue 1430 Broadway, 20th Floor Treasurer’s Message 82 Safety Zone Burbank, CA 91505 New York, NY 10018 Anthony M. DePaulo John Ford 5th Vice President 11th Vice President 6 IATSE and Labor 83 On the Show Floor 1430 Broadway, 20th Floor 326 West 48th Street New York, NY 10018 New York, NY 10036 Movement News Damian Petti John M. -

The Contribution of Czech Musicians to Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Musical Life in Slovenia

The Contribution of Czech Musicians to Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Musical Life in Slovenia Jernej Weiss Studies so far have not given a thorough and comprehensive overview of the activities of Czech musicians in the musical culture of Slovenia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. This article thus deals with the question of the musical, social and cultural influences of Czech musicians in Slovenia in the period discussed. More precisely: in which areas, how and to what extent did in particular the most important representatives of the Czech musicians in Slovenia contribute? The numerous Czech musicians working in Slovenia in the 19th and early 20th century actively co-created practically all areas of musical culture in Slovenia. Through their acti- vities they decisively influenced the musical-creative, musical-reproductive, musical-peda- gogical and musical-publicist areas, and strongly influenced the transition from a more or less musically inspired dilettantism to a gradual rise in terms of quality and quantity of musical culture in Slovenia. Those well-educated Czech musicians brought to Slovenia the creative achievements of musical culture in Czech lands. Taking into account the prevalent role of Czech musicians in Slovenia, there arises the question whether – with regard to the period in question – it might be at all reasonable to speak of “Slovenian Music History” or better to talk about “History of Music in Slovenia”. It is quite understandable that differences exist between music of different provenances; individual musical works are therefore not only distinguished by their chronological sequence and related changes in style, but also by different geographic or sociological (class, cultural, and even ethnic) backgrounds.1 Yet the clarity of these characteristics varies, for they cannot be perceived in precisely the same way or observed with the same degree of reliability in a musical work.2 In this respect, the national component causes considerable difficulties. -

Sustainable Financing Review for Croatia Protected Areas

The World Bank Sustainable Financing Review for Croatia Protected Areas October 2009 www.erm.com Delivering sustainable solutions in a more competitive world The World Bank /PROFOR Sustainable Financing Review for Croatia Protected Areas October 2009 Prepared by: James Spurgeon (ERM Ltd), Nick Marchesi (Pescares), Zrinca Mesic (Oikon) and Lee Thomas (Independent). For and on behalf of Environmental Resources Management Approved by: Eamonn Barrett Signed: Position: Partner Date: 27 October 2009 This report has been prepared by Environmental Resources Management the trading name of Environmental Resources Management Limited, with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the Contract with the client, incorporating our General Terms and Conditions of Business and taking account of the resources devoted to it by agreement with the client. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. This report is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known. Any such party relies on the report at their own risk. Environmental Resources Management Limited Incorporated in the United Kingdom with registration number 1014622 Registered Office: 8 Cavendish Square, London, W1G 0ER CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 BACKGROUND 1 1.2 AIMS 2 1.3 APPROACH 2 1.4 STRUCTURE OF REPORT 3 1.5 WHAT DO WE MEAN BY SUSTAINABLE FINANCE 3 2 PA FINANCING IN CROATIA 5 2.1 CATEGORIES OF PROTECTED -

Proforma Faktura 5

Razvrstavanje otoka u skupine (Članak 2. Zakona o otocima /Narodne novine N 34/99, 149/99, 32/02, 33/06/) „Otoci se glede demografskog stanja i gospodarske razvijenosti razvrstavaju u dvije skupine. U prvoj skupini su sljedeći otoci i otočići: – nedovoljno razvijeni i nerazvijeni: Unije, Susak, Srakane Vele, Srakane Male, Ilovik, Goli, Sv. Grgur, Premuda, Silba, Olib, Škarda, Ist, Molat, Dugi otok, Zverinac, Sestrunj, Rivanj, Rava, Iž, Ošljak, Babac, Vrgada, Prvić (šibensko otočje), Zlarin, Krapanj, Kaprije, Žirje, Veli i Mali Drvenik, Vis, Biševo, Lastovo, Mljet, Šipan, Lopud, Koločep i Lokrum; – mali, povremeno nastanjeni i nenastanjeni: otočići pred Porečom: Frižital, Perila, Reverol, Sv. Nikola, Veliki Školj; otočići pred Vrsarom: Cavata, Figarolica, Galiner, Galopun, Gusti Školj, Kuvrsada, Lakal, Lunga, Salamun, Sv. Juraj, Školjić, Tovarjež, Tuf; otočići pred Rovinjem: Banjol, Figarola, Figarolica, Gustinja, Kolona, Mala Sestrica, Maškin, Pisulj, Pulari, Sturag, Sv. Katarina, Sv. Andrija, Sv. Ivan, Vela Sestrica, Veštar; brijunski otočići: Galija, Gaz, Grunj, Kotež, Krasnica, Mali Brijun, Pusti, Obljak, Supin, Sv. Jerolim, Sv. Marko, Veli Brijun, Vrsar; otočići pred Pulom: Andrija, Fenoliga, Frašker, Fraškerić, Katarina, Uljanik, Veruda; otočići u medulinskom zaljevu: Bodulaš, Ceja, Fenera, Levan, Levanić, Pomerski školjić, Premanturski školjić, Šekovac, Trumbuja; okolni otočići otoka Cresa: Kormati, Mali Ćutin, Mali Plavnik, Veli Ćutin, Visoki, Zeča; okolni otočići otoka Krka: Galun, Košljun, Plavnik, Prvić, Sv. Marko, Školjić, Zečevo; okolni otočići otoka Lošinja: Karbarus, Koludarc, Kozjak, Male Orjule, Mali Osir, Mišnjak, Murtar, Oruda, Palacol, Samuncel, Sv. Petar, Trasorka, Vele Srakane, Male Srakane, Vele Orjule, Veli Osir, Zabodaski; otočići u Vinodolskom i Velebitskom kanalu te Novigradskom i Karinskom moru: Lisac, Mali Ražanac, Mišjak, Sv. Anton, Sv. -

American Foreign Policy, the Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Dissertations Department of History Spring 5-10-2017 Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War Mindy Clegg Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss Recommended Citation Clegg, Mindy, "Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/58 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MUSIC FOR THE INTERNATIONAL MASSES: AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY, THE RECORDING INDUSTRY, AND PUNK ROCK IN THE COLD WAR by MINDY CLEGG Under the Direction of ALEX SAYF CUMMINGS, PhD ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the connections between US foreign policy initiatives, the global expansion of the American recording industry, and the rise of punk in the 1970s and 1980s. The material support of the US government contributed to the globalization of the recording industry and functioned as a facet American-style consumerism. As American culture spread, so did questions about the Cold War and consumerism. As young people began to question the Cold War order they still consumed American mass culture as a way of rebelling against the establishment. But corporations complicit in the Cold War produced this mass culture. Punks embraced cultural rebellion like hippies. -

Operetta After the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen a Dissertation

Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2013 © 2013 Ulrike Petersen All Rights Reserved Abstract Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This thesis discusses the political, social, and cultural impact of operetta in Vienna after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. As an alternative to the prevailing literature, which has approached this form of musical theater mostly through broad surveys and detailed studies of a handful of well‐known masterpieces, my dissertation presents a montage of loosely connected, previously unconsidered case studies. Each chapter examines one or two highly significant, but radically unfamiliar, moments in the history of operetta during Austria’s five successive political eras in the first half of the twentieth century. Exploring operetta’s importance for the image of Vienna, these vignettes aim to supply new glimpses not only of a seemingly obsolete art form but also of the urban and cultural life of which it was a part. My stories evolve around the following works: Der Millionenonkel (1913), Austria’s first feature‐length motion picture, a collage of the most successful stage roles of a celebrated -

HIKING in SLOVENIA Green

HIKING IN SLOVENIA Green. Active. Healthy. www.slovenia.info #ifeelsLOVEnia www.hiking-biking-slovenia.com |1 THE LOVE OF WALKING AT YOUR FINGERTIPS The green heart of Europe is home to active peop- le. Slovenia is a story of love, a love of being active in nature, which is almost second nature to Slovenians. In every large town or village, you can enjoy a view of green hills or Alpine peaks, and almost every Slove- nian loves to put on their hiking boots and yell out a hurrah in the embrace of the mountains. Thenew guidebook will show you the most beauti- ful hiking trails around Slovenia and tips on how to prepare for hiking, what to experience and taste, where to spend the night, and how to treat yourself after a long day of hiking. Save the dates of the biggest hiking celebrations in Slovenia – the Slovenia Hiking Festivals. Indeed, Slovenians walk always and everywhere. We are proud to celebrate 120 years of the Alpine Associati- on of Slovenia, the biggest volunteer organisation in Slovenia, responsible for maintaining mountain trails. Themountaineering culture and excitement about the beauty of Slovenia’s nature connects all generations, all Slovenian tourist farms and wine cellars. Experience this joy and connection between people in motion. This is the beginning of themighty Alpine mountain chain, where the mysterious Dinaric Alps reach their heights, and where karst caves dominate the subterranean world. There arerolling, wine-pro- ducing hills wherever you look, the Pannonian Plain spreads out like a carpet, and one can always sense the aroma of the salty Adriatic Sea.