The First Amendement and New Media: Video Games As Protected Speech and the Implications for the Right of Publicity, 52 B.C.L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ah, the Glorious 1980'S

Jeff Kirkendall’s Thoughts For The Month Column Thoughts, Opinions, Reviews, Commentary & More! Hello and Welcome! My name is Jeff Kirkendall and I'm an independent filmmaker and actor from the Upstate New York area. This is the section of the Very Scary Productions website where I write about topics related to independent filmmaking, digital video production, acting, movies in general, horror movies in particular, my own indie movies, as well as anything and everything related or in between. I decided to create this commentary page because I find that I often come across things that either interest me, excite me, intrigue me, or maybe just bug me. Any topic related to movies and cinema is fair game, from the most mainstream to the most controversial. For example I'll often read about movie projects that I have a strong interest in or opinion on, for one reason or another. This page gives me a forum to discuss these things. It's all about discussion and furthering understanding of our pop culture. Anyone who has feedback concerning what I have to say here, feel free to contact me (see the contact link at http://www.veryscaryproductions.com/). I'd also like to point out that the following is just my opinion, and everyone is free to agree or disagree with what I have to say. Enjoy, and to all the Indies out there: Keep on Filming! SUBJECT: Movie Review – The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters (documentary) Note: The following review of The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters may contain details that could be considered spoilers. -

The Effect of School Closure On

Public Gaming: eSport and Event Marketing in the Experience Economy by Michael Borowy B.A., University of British Columbia, 2008 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art, and Technology Michael Borowy 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Michael Borowy Degree: Master of Arts (Communication) Title of Thesis: Public Gaming: eSport and Event Marketing in the Experience Economy Examining Committee: Chair: David Murphy, Senior Lecturer Dr. Stephen Kline Senior Supervisor Professor Dr. Dal Yong Jin Supervisor Associate Professor Dr. Richard Smith Internal Examiner Professor Date Defended/Approved: July 06, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii STATEMENT OF ETHICS APPROVAL The author, whose name appears on the title page of this work, has obtained, for the research described in this work, either: (a) Human research ethics approval from the Simon Fraser University Office of Research Ethics, or (b) Advance approval of the animal care protocol from the University Animal Care Committee of Simon Fraser University; or has conducted the research (c) as a co-investigator, collaborator or research assistant in a research project approved in advance, or (d) as a member of a course approved in advance for minimal risk human research, by the Office of Research Ethics. -

Kocurek Dissertation 201221.Pdf

Copyright by Carly Ann Kocurek 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Carly Ann Kocurek Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Masculinity at the Video Game Arcade: 1972-1983 Committee: Elizabeth S.D. Engelhardt, Supervisor Janet M. Davis John Hartigan Mark C. Smith Sharon Strover Masculinity at the Video Game Arcade: 1972-1983 by Carly Ann Kocurek, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Acknowledgements Completing a dissertation is a task that takes the proverbial village. I have been fortunate to have found guidance, encouragement, and support from a diversity of sources. First among these, of course, I must count the members of my committee. Thanks in particular to Elizabeth S. D. Engelhardt who, as chair, served as both critic and cheerleader in equal measure and who has guided this project from its infancy. Janet M. Davis’s interest in the sinews that connect popular culture to broader political concerns has shaped my own approach. Mark C. Smith has been a source of support for the duration of my graduate studies; his investment in students, including graduate and undergraduate, is truly admirable. Were it not for a conversation with Sharon Strover in which she suggested I might consider completing some oral histories of video gaming, I might have pursued another project entirely. John Hartigan, through his incisive questions about the politics of race and gender at play in the arcade, shaped my research concerns. -

Everyone Needs to Pitch In”: an Ethnographic Study Of

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School “EVERYONE NEEDS TO PITCH IN”: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF COLLEGIATE ESPORTS A Dissertation in Learning, Design, and Technology by Robert Hein © 2020 Robert Hein Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2020 ii The dissertation of Robert Hein was reviewed and approved by the following: Ty Hollett Assistant Professor of Learning, Design, and Technology Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Simon R. Hooper Professor of Learning, Design, and Technology Stuart A. Selber Associate Professor of English Director of Digital Education Priya Sharma Associate Professor of Learning, Design, and Technology Susan M. Land Associate Professor of Learning, Design, and Technology Director of Graduate Studies iii ABSTRACT Although researchers have shown interest in videogaming since the early 2000s, the hyper- competitive world of “esports” has received less attention. However, multi-million dollar gaming tournaments—such as the 2019 Fortnite World Cup—now make headlines and spark national discussion. Similarly, colleges and universities have begun offering athletic scholarships to students who excel at games like League of Legends and Overwatch. Consequently, this present study aims to shine a light on the values, beliefs, and practices of gaming’s most “hardcore” players and communities. To better understand how these competitors improve their in-game skills, the author adopted a “connective ethnographic” approach and immersed himself in the day-to-day activities of a collegiate esports club. This process involved attending club meetings, interviewing members, and participating alongside players as they competed with and against one another in the game of Overwatch. -

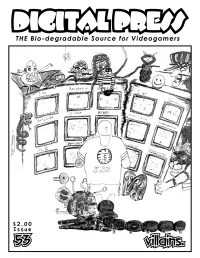

Digital Press Issue

Villains. Editor’s BLURB by Dave Giarrusso DIGITAL reetings, gang! Welcome back for another heapin’ Ghelpin’ of Digital Press goodness. Or badness, since this issue is all about villains! If you’ve been with us for a while, you might remember that we devoted issue #37 to the videogame heroes. In the interest of equal time, we fi gured we’d better get crackin’ on the evil-twin counterpart issue. In the movies, we often see villains who are much more interesting than the PRESS heroes. Star Wars had Luke and Anakin, but everyone wanted to BE Darth Maul or Darth Vader. Everyone, including Anakin himself! Whether or not it’s the promise of unlimited power or those nifty black outfi ts is anyone’s guess. DIGITAL PRESS # 53 In the land of videogames though, it’s typically the heroes who get top JULY / AUGUST 2003 billing. Pac-Man stars in over a dozen different games, but the monsters are Founders Joe Santulli just part of the supporting cast. Pengo kicks so much Sno-Bee ass that casual Kevin Oleniacz gamers don’t even recall the Bees. And really, Donkey Kong was much more Editors-In-Chief Joe Santulli charismatic as a villain. You probably already see where I’m going with this... Dave Giarrusso Sometimes you’ve just gotta be BAD. Whether your stepping into the virtual Senior Editors Al Backiel Jeff Cooper shoes of Donkey Kong, Shang Tsung, Tommy Vercetti, or the Olsen Twins, being John Hardie the bad guy is often much more fun than being the hero. -

BOE Meeting Reveals Redistricting Plans THIS D AY in HISTORY

Rotary Exchange - Page 3 NYC Trips - Page 2 Boys Baseball - Page 5 Woosterthe High School studentwooster newspaper 515 Oldman Road Wooster, OH Marchblade 30, 2011 Volume VII Issue 11 Growing entrepreneurship enriches downtown Wooster FACTS thing that emboldens Wooster. TO MAKE the revitalization of With the future of the YOU downtown Wooster is downtown area in mind, 5SMARTER the teamwork within Erdos stressed how he downtown entrepreneurs. would like to see more “In this area of town, local businesses start up we’re all friends. It’s not and breathe even more a competition between life into a scene that is businesses…We know that teeming with opportunity The Hunger1 Games film if one of us does well, we for a successful business. grossed $155 million in all do well,” Rousseau said. Jordan Smith, co-owner opening weekend. Perhaps a good example of Spoon, a mini-market www.imdb.com of this teamwork lies a that offers fine meats, couple hundred feet down sandwiches, beverages from SoMar on South and other assorted Market street, in the newly goods, agrees with Erdos. opened St. Paul hotel. “I would definitely like Bill Erdos, owner of the to see more locally owned A new record was set NOAH SPECTOR 2 hotel, knew exactly what businesses on this side for Cleveland after 11 Spoon Market, owned by Jeff, Jordan and Patrice Smith, is one of the opening of the St. Paul of town,” Smith said. straight days of 70 degree several new businesses helping to modernize downtown Wooster. Hotel would do not only Given the success and weather. -

Movie Museum FEBRUARY 2008 COMING ATTRACTIONS

Movie Museum FEBRUARY 2008 COMING ATTRACTIONS THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY Happy Chinese New Year! THE ASSASSINATION OF Hawaii Premiere! ACROSS THE UNIVERSE Oahu Premiere! RATATOUILLE JESSE JAMES BY THE THE KING OF KONG: A (2007) IRA AND ABBY (2007) COWARD ROBERT FORD FISTFUL OF QUARTERS in widescreen (2006) animation in widescreen (2007) (2008) in widescreen voiced by Patton Oswalt, Ian with Evan Rachel Wood, Jim in widescreen in widescreen Sturgess, Joe Anderson, Dana Chris Messina, Fred Willard, Holm, Lou Romano, Brian with Brad Pitt, Mary-Louise Dennehy, Peter O'Toole, In this acclaimed doc, a Fuchs, Martin Luther, T.V. Jason Alexander, Robert Klein, Parker, Brooklynn Proulx, Jennifer Westfeldt, Frances Janeane Garofalo, Brad Casey Affleck, Sam Rockwell, science teacher challenges Carpio, Joe Cocker, Bono, Garrett, Will Arnett. Sam Shepard. a hot sauce tycoon for the Salma Hayek, Eddie Izzard. Conroy, Maddie Corman. Donkey Kong world title. Directed and Co-written by Directed by Directed by Directed by Written and Co-Directed by Robert Cary. Brad Bird Andrew Dominik. Seth Gordon. Julie Taymor. 1, 4 & 7pm 2, 4, 6 & 8pm 12:30, 3, 5:30 & 8pm 2, 4, 6 & 8pm 12:30, 3, 5:30 & 8pm 7 8 9 10 11 Happy Valentine's Day! BECOMING JANE Oahu Premiere! BECOMING JANE Presidents' Day VALENTÍN (2007-UK) IRA AND ABBY (2007-UK) THE ASSASSINATION OF (2002-Argentina/Netherlands/ in widescreen (2006) in widescreen JESSE JAMES BY THE France/Italy/Spain) with Anne Hathaway, James in widescreen with Anne Hathaway, James COWARD ROBERT FORD in Spanish with English McAvoy, Julie Walters, James Chris Messina, Fred Willard, McAvoy, Julie Walters, James (2007) subtitles & in widescreen Cromwell, Maggie Smith, Joe Jason Alexander, Robert Klein, Cromwell, Maggie Smith, Joe in widescreen Anderson, Jessica Ashworth, Jennifer Westfeldt, Frances Anderson, Jessica Ashworth, with Brad Pitt, Mary-Louise with Rodrigo Noya, Carmen Lucy Cohu, Laurence Fox. -

Twin Galaxies Superstars of Video Games Compilation 001-600

SetYear Sport CardNumber DefaultDescription MGDescription BKDescription SetName TeamName OtherAttributes Serialnum PrintRun RC Autograph Memorabilia Type Genre Property Character SetType Flags Factor Brand Manufacturer SourceSet Notes Player Serial Seeding SetFactor 2011 non-sports Cover Card for Series "C" Limited Series - Only 200 copies printed Walter Day Collection Superstars of 2011 Cards - NonSports m b The Walter Day Collection 2011 non-sports 1 Paul Zimmerman Walter Day Collection Superstars of 2011 Cards - NonSports m b The Walter Day Collection 2011 non-sports 1 Billy Mitchell color Color Walter Day Collection Superstars of 2011 Cards - NonSports m b The Walter Day Collection 2011 non-sports 1 Billy Miller color/25 Color - 25 copies printed Walter Day Collection Superstars of 2011 serial 25 25 Cards - NonSports m b The Walter Day Collection 2011 non-sports 1B Billy Miller Grayscale/117 Grayscale - 117 copies printed Walter Day Collection Superstars of 2011 serial 117 117 Cards - NonSports m b The Walter Day Collection 2011 non-sports 1C Billy Mitchell Grayscale/117 Grayscale - 117 copies printed Walter Day Collection Superstars of 2011 serial 117 117 Cards - NonSports m b The Walter Day Collection 2011 non-sports 2 Ralph Baer ERR#{marketing toy agnate/20 Error card - 20 copies distributed with backside typo (marketing toy agnate…) Walter Day Collection Superstars of 2011 serial 20 20 Cards - NonSports m b The Walter Day Collection 2011 non-sports 2 Ralph Baer COR Corrected card issued Walter Day Collection Superstars of 2011 -

Nox Archaist Man Vs

WWW.OLDSCHOOLGAMERMAGAZINE.COM ISSUE #4 • MAY 2018 MAY 2018 • ISSUE #4 RPGS REVIEW A Selected History of RPGs Boss Fight Books 06 BY TODD FRIEDMAN 29 BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER RPGS NEWS Role Playing Games Convention Update 08 BY JASON RUSSELL 30 BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER RPGs VIDEO GAME MOVIE REVIEW Nox Archaist Man vs. Snake 10 BY BILL LANGE 36 BY BRAD FEINGOLD RPGs FEATURE Just For Qix: Cadash 45 Years of Arcade Gaming: The 1990s 12 BY MICHAEL THOMASSON 38 BY ADAM PRATT NEWS THE GAME SCHOLAR 2018 Old School Event Calendar Keyboard Creations 14 BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER 44 BY LEONARD HERMAN RPGs PUREGAMING.ORG INFO Wizardry Talk Sega 32x and Sega CD 15 BY KEVIN BUTLER 47 BY PUREGAMING.ORG RPGs Evolution of Role-Playing Games 17 In Japan BY ANTOINE CLERC-RENAUD RPGs Lord British Meetup 19 BY BILL LANGE RPGs Publisher Business Manager Issue Writers Ryan Burger Aaron Burger Todd Friedman, Jason Brett’s Old School Bargain Bin Russell, Bill Lange, 20 Dungeons and Dragons Editor Design Director Michael Thomasson, BY BRETT WEISS Brian Szarek Jacy Leopold Antoine Clerc-Renaud, Brett Weiss, Walter Day, THE WALTER DAY REPORT Editorial Board Design Assistant Jonathan Polan, Todd Dan Loosen Marc Burger Friedman, Brad Feingold, G.O.A.T.’s of the 21st Century Doc Mack Adam Pratt, Leonard 22 BY WALTER DAY Billy Mitchell Art Director Herman Walter Day Thor Thorvaldson INTERVIEW/PEOPLE A Few Minutes with Buck Stein BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER HOW TO REACH OLD SCHOOL GAMER: Postmaster – Send address changes to: 24 OSG • 222 SE Main St • Grimes IA 50111 515-986-3344 Postage paid at Grimes, IA and other mailing locations. -

45 Years of Arcade Gaming

WWW.OLDSCHOOLGAMERMAGAZINE.COM ISSUE #2 • JANUARY 2018 Midwest Gaming Classic midwestgamingclassic.com CTGamerCon .................. ctgamercon.com JANUARY 2018 • ISSUE #2 EVENT UPDATE BRETT’S BARGAIN BIN Portland Classic Gaming Expo Donkey Kong and Beauty and the Beast 06 BY RYAN BURGER 38BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER STAFF WE DROPPED BY FEATURE Old School Pinball and Arcade in Grimes, IA 45 Years of Arcade Gaming: 1980-1983 08 BY RYAN BURGER 40BY ADAM PRATT THE WALTER DAY REPORT THE GAME SCHOLAR When President Ronald Reagan Almost Came The Nintendo Odyssey?? 10 To Twin Galaxies 43BY LEONARD HERMAN BY WALTER DAY REVIEW NEWS I Didn’t Know My Retro Console Could Do That! 2018 Old School Event Calendar 45 BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER STAFF 12 BY RYAN BURGER FEATURE REVIEW Inside the Play Station, Enter the Dragon Nintendo 64 Anthology 46 BY ANTOINE CLERC-RENAUD 13 BY KELTON SHIFFER FEATURE WE STOPPED BY Controlling the Dragon A Gamer’s Paradise in Las Vegas 51 BY ANTOINE CLERC-RENAUD 14 BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER STAFF PUREGAMING.ORG INFO GAME AND MARKET WATCH Playstation 1 Pricer Game and Market Watch 52 BY PUREGAMING.ORG 15 BY DAN LOOSEN EVENT UPDATE Free Play Florida Publisher 20BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER STAFF Ryan Burger WESTOPPED BY Business Manager Aaron Burger The Pinball Hall of Fame BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER STAFF Design Director 22 Issue Writers Kelton Shiffer Jacy Leopold MICHAEL THOMASSON’S JUST 4 QIX Ryan Burger Michael Thomasson Design Assistant Antoine Clerc-Renaud Brett Weiss How High Can You Get? Marc Burger Walter Day BY MICHAEL THOMASSON 24 Brad Feingold Editorial Board Art Director KING OF KONG/OTTUMWA, IA Todd Friedman Dan Loosen Thor Thorvaldson Leonard Herman Doc Mack Where It All Began Dan Loosen Billy Mitchell BY SHAWN PAUL JONES + WALTER DAY Circulation Manager Walter Day 26 Kitty Harr Shawn Paul Jones Adam Pratt KING OF KONG/OTTUMWA, IA King of Kong Movie Review 28 BY BRAD FEINGOLD HOW TO REACH OLD SCHOOL GAMER: Tel / Fax: 515-986-3344 Postage paid at Grimes, IA and additional mailing KING OF KONG/OTTUMWA, IA Web: www.oldschoolgamermagazine.com locations. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

1 David A. Tashroudian [SBN 266718] Mona Tashroudian [SBN 272387] 2 TASHROUDIAN LAW GROUP, APC 12400 Ventura Blvd., Suite 300 3 Studio City, California 91604 Telephone: (818) 561-7381 4 Facsimile: (818) 561-7381 Email: [email protected] 5 [email protected] 6 Attorneys for Defendant Twin Galaxies, LLC 7 8 SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 9 COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES 10 11 WILLIAM JAMES MITCHELL, Case No. 19STCV12592 12 Plaintiff, Assigned to: Hon. Gregory W. Alarcon [Dept. 36] 13 v. DEFENDANT TWIN GALAXIES, LLC’S 14 MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE CROSS- 15 TWIN GALAXIES, LLC; and Does 1-10, COMPLAINT; DECLARATION OF DAVID A. TASHROUDIAN IN SUPPORT 16 Defendants. [CCP § 426.50] 17 [Filed concurrently with [Proposed] Order] 18 Hearing 19 Date: December 11, 2020 Time: 8:30 a.m. 20 Place: Department 36 21 RESERVATION ID: 487165978456 22 Action Filed: 4/11/2019 23 24 25 26 27 28 1 MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE CROSS-COMPLAINT 1 NOTICE OF MOTION AND MOTION 2 TO THE HONORABLE COURT, AND TO ALL ATTORNEYS OF RECORD: 3 PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that on December 11, 2020 at 8:30 a.m., or as soon thereafter 4 as the matter may be heard in Department 36 of the above entitled court, located at 111 N. Hill 5 Street, Los Angeles, California 90012, defendant Twin Galaxies, LLC ( “Defendant”) will and 6 hereby does move, pursuant to the provisions of the California Code of Civil Procedure section 7 426.50 for leave to file its cross-complaint against William James Mitchell (“Plaintiff”), and 8 Walter Day. -

The King of Kong: a Fistful of Quarters Gordon B

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Opus: Research and Creativity at IPFW Indiana University - Purdue University Fort Wayne Opus: Research & Creativity at IPFW Organizational Leadership and Supervision Faculty Division of Organizational Leadership and Publications Supervision 12-2016 The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters Gordon B. Schmidt Indiana University - Purdue University Fort Wayne, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.ipfw.edu/ols_facpubs Part of the Industrial and Organizational Psychology Commons, and the Organizational Behavior and Theory Commons Opus Citation Gordon B. Schmidt (2016). The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters. Journal of Management Education.39 (6), 801-811. Sage. http://opus.ipfw.edu/ols_facpubs/90 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Division of Organizational Leadership and Supervision at Opus: Research & Creativity at IPFW. It has been accepted for inclusion in Organizational Leadership and Supervision Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Opus: Research & Creativity at IPFW. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JMEXXX10.1177/1052562915587584Journal of Management EducationSchmidt 587584research-article2015 Resource Reviews Journal of Management Education 2015, Vol. 39(6) 801 –811 The King of Kong: A © The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: Fistful of Quarters sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1052562915587584 jme.sagepub.com Reviewed by: Gordon B. Schmidt, Indiana University Purdue University Fort Wayne, USA Resource Description The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters (2007, Picturehouse, 90 minutes) is a documentary that chronicles the attempt of Steve Wiebe to become recog- nized as the world record holder of the classic arcade game Donkey Kong (Cunningham & Gordon, 2007).