Expo 67, Or the Architecture of Late Modernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why the Battle for IKEA's New Atlantic Canada Store Was Over Before It

BUSINESS ATTRACTION The Big Deal Why the battle for IKEA’s new Atlantic Canada store was over before it started By Stephen Kimber atlanticbusinessmagazine.com | Atlantic Business Magazine 119 Date:16-04-20 Page: 119.p1.pdf consumers in the Halifax area, but it’s also in the crosshairs of a web of major highways that lead to and from every populated nook and cranny in Nova Scotia, not to forget New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, making it a potential shopping destination for close to two million Maritimers. No wonder its 500-acre site already boasts 1.3 million square feet of shopaholic heaven with over 100 retailers and services, including five of those anchor-type destinations: Walmart, Home Depot, Costco, Canadian Tire and Cineplex Cinemas. Glenn Munro was apologetic. I’d been All it needed was an IKEA. calling and emailing him to follow up on January’s announcement that IKEA — the iconic Swedish furniture retailer with 370 stores and $46.6 billion in sales worldwide y now, the IKEA creation last year — would build a gigantic (for us story has morphed into myth: Bin 1947, Ingvar Kamprad, at least) $100-million, 328,000-square- an eccentric, dyslexic 17-year-old foot retail store in Dartmouth Crossing. He Swedish farm boy, launched a mail-order company called IKEA. hadn’t responded. He’d invented the name using his initials and his home district. Soon after, he also invented the “flat I wanted to know how and why pack” to more efficiently package IKEA had settled on Halifax and and ship his modernist build-it- not, say, Moncton as the site for 328,000 yourself furniture. -

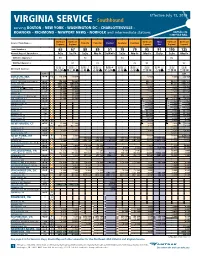

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

World's Fairs Collection, 1893-1965

World’s Fairs Collection, 1893-1967. Special Collections Department/Long Island Studies Institute Contact Information: Special Collections Department Axinn Library, Room 032 123 Hofstra University Hempstead, NY 11549 Phone: (516) 463-6411, or 463-6404 Fax: (516) 463-6442 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.hofstra.edu/Libraries/SpecialCollections Compiled by: [J. Boucher] Last updated by: Date Completed: [Oct. 2004] [M. O’Connor] [Jan. 16, 2018] World’s Fairs Collection, 1893-1965 2.9 cu. ft. The collection contains materials related to the World’s Fairs held in Chicago, Illinois (1893 and 1933-1934); Buffalo, New York (1901); St. Louis, Missouri (1904); Queens, New York (1939- 1940 and 1964-1965); and Montreal, Canada (1967). Included are business records, DVDs, ephemera, maps, memorabilia, news clippings, newspapers, postcards, printed materials, and publications. Noteworthy items include a souvenir postcard of the Electricity Building at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, and a number of guides and maps to the New York World’s Fairs of 1939-1940 and 1964-1965. SUBJECTS Names: Century of Progress International Exposition (1933-1934 : Chicago, Ill.). Expo (International Exhibitions Bureau) (1967 : Montréal, Québec) Louisiana Purchase Exposition (1904 : Saint Louis, Mo.). New York World’s Fair (1939-1940). New York World’s Fair (1964-1965). Pan-American Exposition (1901: Buffalo, N.Y.) World’s Columbian Exposition (1893 : Chicago, Ill.). Subjects: Exhibitions Places: Buffalo (New York)--History Chicago, Ill.--History. Flushing (New York, N.Y.)--History. Montréal (Canada)--History. St. Louis, MO.--History. Form and Genre Terms: Business records. DVD-Video discs. Ephemera. Maps. Memorabilia. News clippings. Newspapers. Postcards. -

IAWA Center News Fall 2012 No

INTERNATIONAL ARCHIVE OF WOMEN IN ARCHITECTURE IAWA Center News Fall 2012 No. 24 EDITOR’S NOTE By Helene Renard In this issue of the newsletter, we focus on materials and new collections that have come into the Archive. Labelle Prussin’s work focuses on indigenous African building methods. K.C. Arceneaux comments on two of Prussin’s books that have been added to the Archive. Wendy Bertrand’s collection consists of many boxes of materials, documenting her personal and professional life. Professor Marcia Feuerstein reviews Bertrand’s book, Enamored with Place, and I uncover some of her fiber arts creations. We are adding a new feature to the newsletter with Lindsay Nencheck’s piece about her residency and research at the IAWA made possible by the Milka Bliznakov Research Prize. Finally, “A Note from the Chair” provides an overview of the past year’s activities at the IAWA Center. We thank you for your continued interest and support. Fulbe women erecting a matframe tent, north of Bamako, Mali. Photo from Hatumere: Islamic Design in West Africa THE IAWA ADDS BOOKS OF AFRICANIST by Dr. Labelle Prussin, 1986. LABELLE PRUSSIN TO THE COLLECTION Dr. Prussin’s contributions to the history, theory, and practice of By K. C. Arceneaux, Ph. D. architecture have spanned four decades. She graduated from the University of California (1952), and Yale (Ph.D., 1973). Her The IAWA is pleased to have acquired for the International teaching appointments have included positions at the University Archive of Women in Architecture, three monographs by the of Science and Technology in Ghana; the University of Michigan; esteemed architect, historian, and Africanist, Labelle Prussin. -

Moshe Safdie Habitat Puerto Rico

MosheMoshe Safdie Safdie 130 • Constelaciones nº6, 2018. ISSN: 2340-177X Habitat PuertoHabitat Rico Puerto, 1968 Rico Fecha recepción Receipt date 29/09/2017 Fechas evaluación Evaluation dates 20/10/2017 & 20/10/2017 Fecha aceptación Acceptance date 11/01/2018 Fecha publicación Publication date 01/06/2018 La pantalla dividida, composición y descomposición visual. Film y espacio, Montreal, 1967 The Divided Screen, Composition and Visual Decomposition. Film and Space, Montreal, 1967 Sofía Quiroga Fernández Xi´an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, China Traducción Translation Sofía Quiroga Fernández Palabras clave Keywords Experiencia total, exposición universal, pantallas, proyección, tecnología audiovisual, Montreal. Total experience, universal exhibition, screens, projection, audiovisual technologies, Montreal. Resumen Abstract La Exposición Universal de Montreal de 1967 representa uno de los entor- The 1967 Montreal Universal Exhibition represents one of the most nos experimentales más importante del siglo en cuanto a los medios de important experimental environment of the century to media, distin- comunicación, distinguiéndose respecto a los anteriores por su particular guishing itself from the earlier ones due to its particular use of screens uso de las tecnologías audiovisuales, la reivindicación de las pantallas y las and audiovisual technologies, as well as the new theatrical typologies nuevas tipologías teatrales desarrolladas para dar cabida a nuevas formas developed to fit with the new ways of projection. This article explores de proyección. El presente artículo explora algunas de las propuestas de- some of the proposals developed in Montreal, where space and tech- sarrolladas en Montreal, donde espacio y tecnología trabajan de manera nology worked together looking for a total experience. conjunta en pos de una experiencia total. -

Men's 100M Diamond Discipline 13.07.2021

Men's 100m Diamond Discipline 13.07.2021 Start list 100m Time: 19:25 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Isiah YOUNG USA 9.69 9.89 9.89 WR 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM Olympiastadion, Berlin 16.08.09 2 Chijindu UJAH GBR 9.87 9.96 10.03 AR 9.86 Francis OBIKWELU POR Olympic Stadium, Athina 22.08.04 3André DE GRASSECAN9.849.909.99=AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Paris 04.07.15 =AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Montreuil-sous-Bois 07.06.16 4 Trayvon BROMELL USA 9.69 9.77 9.77 NR 9.87 Linford CHRISTIE GBR Stuttgart 15.08.93 5Fred KERLEYUSA9.699.869.86WJR 9.97 Trayvon BROMELL USA Eugene, OR 13.06.14 6Zharnel HUGHESGBR9.879.9110.06MR 9.78 Tyson GAY USA 13.08.10 7 Michael RODGERS USA 9.69 9.85 10.00 DLR 9.69 Yohan BLAKE JAM Lausanne 23.08.12 8Adam GEMILIGBR9.879.9710.14SB 9.77 Trayvon BROMELL USA Miramar, FL 05.06.21 2021 World Outdoor list Medal Winners Road To The Final 9.77 +1.5 Trayvon BROMELL USA Miramar, FL (USA) 05.06.21 1Ronnie BAKER (USA) 16 9.84 +1.2 Akani SIMBINE RSA Székesfehérvár (HUN) 06.07.21 2019 - IAAF World Ch. in Athletics 2 Akani SIMBINE (RSA) 15 9.85 +1.5 Marvin BRACY USA Miramar, FL (USA) 05.06.21 1. Christian COLEMAN (USA) 9.76 3 Lamont Marcell JACOBS (ITA) 13 9.85 +0.8 Ronnie BAKER USA Eugene, OR (USA) 20.06.21 2. -

Officieele Gids Voor De Olympische Spelen Ter Viering Van De Ixe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928

Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 samenstelling Nederlands Olympisch Comité bron Nederlands Olympisch Comité (samenstelling), Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928. Holdert & Co. en A. de la Mar Azn., z.p. z.j. [Amsterdam ca. 1928] Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_ned016offi01_01/colofon.htm © 2009 dbnl 1 [advertentie] Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 2 [advertentie] Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 3 [advertentie] Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 4 [advertentie] Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 5 [advertentie] Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 6 [advertentie] Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 7 Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade Amsterdam 1928 UITGEGEVEN MET MEDEWERKING VAN HET COMITÉ 1928 (NED. OLYMPISCH COMITÉ) UITGAVE HOLDERT & Co. en A. DE LA MAR Azn. Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 8 Mr. A. Baron Schimmelpenninck van der Oye Voorzitter der Olympische Spelen 1928 Président du Comité Exécutif 1928 Vorsitzender des Vollzugsausschusses 1928 President of the Executive Committee 1928 Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 9 Voorwoord. Een kort woord ter aanbeveling van den officieelen Gids. -

ANZ: Building a Super Regional Bank

Asia Investor Update Brand Nancy Wong GM, Strategy & Marketing APEA 10 June 2010 ANZ: Building a Super Regional Bank 28 We have rolled out a refreshed brand across our markets Old Brand New Brand 29 29 Our new Chinese name signifies our continued commitment to Greater China … • The name ‘Ao Sheng Yin Hang’ will represent ANZ in all the Chinese markets we operate • „Ao‟ is an abbreviation for Australia. It also means a deep and wide bay. Water is an auspicious symbol of wealth in traditional Chinese and many Asian cultures • „Sheng‟ represents flourishing riches and prosperity • Taiwanese press stories on the launch of the Chinese brand 30 …and we launched the Chinese expression of “We live in your world” to be closer to our customers The Chinese tagline ‘zhi xin, suo yi chuang xin’ translates in English to „Understanding you, we can create new possibilities‟. It expresses the essence of our global tagline, „We live in your world‟. 31 A systematic brand building is underway across Asia built around the RBS acquisition Sequentially delivering the key elements of our customer proposition „Commitment‟ „Stability & Strength‟ „Listening and ‟Connectivity across Understanding‟ the region‟ 32 … through carefully selected media to target institutional / commercial / HNW / affluent clients Bloomberg Website Bloomberg TV Airports Business Newspapers Financial Times Wall Street Journal 33 We are leveraging our sponsorships to drive brand & business engagement Australian Open Tennis Hong Kong Rugby Sevens 34 Our Platinum Sponsorship of the Australian -

Venice's Giardini Della Biennale and the Geopolitics of Architecture

FOLKLORIC MODERNISM: VENICE’S GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE AND THE GEOPOLITICS OF ARCHITECTURE Joel Robinson This paper considers the national pavilions of the Venice Biennale, the largest and longest running exposition of contemporary art. It begins with an investigation of the post-fascist landscape of Venice’s Giardini della Biennale, whose built environment continued to evolve in the decades after 1945 with the construction of several new pavilions. With a view to exploring the architectural infrastructure of an event that has always billed itself as ‘international’, the paper asks how the mapping of national pavilions in this context might have changed to reflect the supposedly post-colonial and democratic aspirations of the West after the Second World War. Homing in on the nations that gained representation here in the 1950s and 60s, it looks at three of the more interesting architectural additions to the gardens: the pavilions for Israel, Canada and Brazil. These raise questions about how national pavilions are mobilised ideologically, and form/provide the basis for a broader exploration of the geopolitical superstructure of the Biennale as an institution. Keywords: pavilion, Venice Biennale, modernism, nationalism, geopolitics, postcolonialist. Joel Robinson, The Open University Joel Robinson is a Research Affiliate in the Department of Art History at the Open University and an Associate Lecturer for the Open University in the East of England. His main interests are modern and contemporary art, architecture and landscape studies. He is the author of Life in Ruins: Architectural Culture and the Question of Death in the Twentieth Century (2007), which stemmed from his doctoral work in art history at the University of Essex, and he is co-editor of a new anthology in art history titled Art and Visual Culture: A Reader (2012). -

Historic Map of Commuter Rail, Interurbans, and Rapid

l'Assomption Montreal Area Historical Map of Interurban, Commuter Rail and Rapid Transit Legend Abandoned Interurban Line St-Lin Abandoned Line This map aims to show the extensive network of interurban,* commuter rail, On-Street (Frequent Stops) (Expo Express) Abandoned Rail Line Acitve Line and rapid transit lines operated in the greater Montreal Region. The city has St-Paul-l'Ermite (Metro) Active Rail Line Abandoned Station seen a dramatic changes in the last fifty years in the evolution of rail transit. La Ronde (Expo Express) La Plaine Streetcars and Interurbans have come and gone, and commuter rail was Viger Abandoned Station Active Stations Bruchesi Du College Abandoned dwindled down to two lines and is now up to three. Over these years the Metro Charlemange / Repentigny Temporary Station Parc Blue Line Longueuil Le Page Chambly was built as was the now dismantled Expo Express. Abandoned Interurban Stop Yellow Line Square-Victoria Orange Line Granby Abandoned Interurban Station Ravins Then Abandoned Rail Station McGill Green Line -Eric Peissel, Author Pointe-aux-Trembles Pointe Claire Active Station A special thanks to all who helped compile this map: [Lakeside] [with Former Name] Blainville Snowdon Interchange Station Tom Box, Hugh Brodie, Gerry Burridge, Marc Dufour, Louis Desjardins, James Hay, Mont-Royal Active Station Paul Hogan, C.S. Leschorn, & Pat Scrimgeor Pointe-aux- Trembles Sainte-Therese Riviere-des-Prairies Sources: Leduc, Michael Montreal Island Railway Stations - CNR Rosemere Ste-Rosalie-Jct. Sainte-Rose St-Hyacinthe Leduc, Michael Montreal Island Railway Stations - CPR Lacordaire Montreal-North * Tetreauville Grenville Some Authors have classified the Montreal Park and Island and Montreal Terminal Railway as Interurbans but most authoritive books on Interurbans define Ste. -

History of Mormon Exhibits in World Expositions

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1974 History of Mormon Exhibits in World Expositions Gerald Joseph Peterson Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Peterson, Gerald Joseph, "History of Mormon Exhibits in World Expositions" (1974). Theses and Dissertations. 5041. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5041 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. aloojloo nn HISTORY OF moreonMOMIONMORKON exlEXHIBITSEXI abitsabets IN WELDWRLD expositionsEXPOSI TIMS A thesis presented to the department of church history and doctrine brigham young university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree master of arts by gerald joseph peterson august 1941974 this thesis by gerald josephjoseph peterson isifc accepted in its pre- sent form by the department of church history and doctrine in the college of religious instruction of brighamBrig hainhalhhajn young university as satis- fyjfyingbyj ng the thesis requirements for the degree of master of arts julyIZJWJL11. 19rh biudiugilgilamQM jwAAIcowan completionemplompl e tion THdatee richardlalial0 committeeCowcomlittee chairman 02v -

New Books on Art & Culture

S11_cover_OUT.qxp:cat_s05_cover1 12/2/10 3:13 PM Page 1 Presorted | Bound Printed DISTRIBUTEDARTPUBLISHERS,INC Matter U.S. Postage PAID Madison, WI Permit No. 2223 DISTRIBUTEDARTPUBLISHERS . SPRING 2011 NEW BOOKS ON SPRING 2011 BOOKS ON ART AND CULTURE ART & CULTURE ISBN 978-1-935202-48-6 $3.50 DISTRIBUTED ART PUBLISHERS, INC. 155 SIXTH AVENUE 2ND FLOOR NEW YORK NY 10013 WWW.ARTBOOK.COM GENERAL INTEREST GeneralInterest 4 SPRING HIGHLIGHTS ArtHistory 64 Art 76 BookDesign 88 Photography 90 Writings&GroupExhibitions 102 Architecture&Design 110 Journals 118 MORE NEW BOOKS ON ART & CULTURE Special&LimitedEditions 124 Art 125 GroupExhibitions 147 Photography 157 Catalogue Editor Thomas Evans Architecture&Design 169 Art Direction Stacy Wakefield Forte Image Production Nicole Lee BacklistHighlights 175 Data Production Index 179 Alexa Forosty Copy Writing Sara Marcus Cameron Shaw Eleanor Strehl Printing Royle Printing Front cover image: Mark Morrisroe,“Fascination (Jonathan),” c. 1983. C-print, negative sandwich, 40.6 x 50.8 cm. F.C. Gundlach Foundation. © The Estate of Mark Morrisroe (Ringier Collection) at Fotomuseum Winterthur. From Mark Morrisroe, published by JRP|Ringier. See Page 6. Back cover image: Rodney Graham,“Weathervane (West),” 2007. From Rodney Graham: British Weathervanes, published by Christine Burgin/Donald Young. See page 87. Takashi Murakami,“Flower Matango” (2001–2006), in the Galerie des Glaces at Versailles. See Murakami Versailles, published by Editions Xavier Barral, p. 16. GENERAL INTEREST 4 | D.A.P. | T:800.338.2665 F:800.478.3128 GENERAL INTEREST Drawn from the collection of the Library of Congress, this beautifully produced book is a celebration of the history of the photographic album, from the turn of last century to the present day.