Race, Citizenship, and the Roots of Japanese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effects of Private Memory on the Redress Movement of Japanese Americans

From Private Moments to Public Calls for Justice: The Effects of Private Memory on the Redress Movement of Japanese Americans A thesis submitted to the Department of History, Miami University, in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in History. Sarah Franklin Doran Miami University Oxford, Ohio May 201 ii ABSTRACT FROM PRIVATE MOMENTS TO PUBLIC CALLS FOR JUSTICE: THE EFFECTS OF PRIVVATE MEMORY ON THE REDRESS MOVEMENT OF JAPANESE AMERICANS Sarah Doran It has been 68 years since President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which led to the internment of more than 110,000 Japanese Americans. This period of internment would shape the lives of all of those directly involved and have ramifications even four generations later. Due to the lack of communication between family members who were interned and their children, the movement for redress was not largely popular until the 1970s. Many families classified their time in the internment camps as subjects that were off limits, thus, leaving children without the true knowledge of their heritage. Because memories were not shared within the household, younger generations had no pressing reason to fight for redress. It was only after an opening in the avenue of communication between the generations that the search for true justice could commence. The purpose of this thesis is to explore how communication patterns within the home, the Japanese-American community, and ultimately the nation changed to allow for the successful completion of a reparation movement. What occurred to encourage those who were interned to end their silence and share their experiences with their children, grandchildren, and the greater community? Further, what external factors influenced this same phenomenon? The research for this project was largely accomplished through reading memoirs and historical monographs. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Mrs. Frank Knox Dies;

STAR LEGAL NOTICES PERSONAL THE EVENING (CONTINUED) (CONTINUtO) Washington, D. C. B-11I*s* SEPTEMBER M. your TUESDAY HHK.OK U. BIMHCH. «**•»», PIANOH—Wc «tor« tnd tell Knox Dies; Avenue N.W.. If lnt«r,»tfd in tbD rnnv Mrs. Frank 1601 Connecticut oltno Washington 6. 0. C. plan, writ, P 0 »«3 Etlv«r ! STAR CLASSIFIED LEADS SDrly ,Md _ UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the District of Columbia. Hold- NEAL VALIANT DANCE CLUB. ** ing 05 yr Mtmbcrihip limited. Wkly. or- the ether Washington papers by • Probate Court.—No. <26. Secretary Administration—Tbii Is to Oive chestra. record dtnce oartlen; In- PAY LESS Widow of oi . Notice: That the subscribers. Klruc etc. Per info. ME. the of New York and the deilre, healthy Statu Columbia, reipectlveb ELDERLY WIDOW MIAMI. Fla., Sept. 23 <AP'. District oi white lady under 7(1, or marrlrd have obtained from the Probat# couple Flor- GET MORE! —Mrs. Annie Reid Knox. 82. MILLIONS LINES Court of the District of Columbia, to «hare her home In OF. ida Room and in re- | on estate board free letter* teitamentary the companlomhlp rea- widow of former Secretary of of AONEB THERESA MARTIN, turn lor and j Frank Knox, died ¦ late of the District of Columbia, eonabie service» around houee. | Always the Navy deceased All person* having Call DAUOHTER. OL. 5-740 U, [ ust • home in sub- against deceased are alter «p m. yesterday at her claim* the _ ~ hereby warned to exhibit t)»u »unje, urban Coral Gables. tk- with the vouchers thereof, leaelly ENVELOPES ADDRESSED Fat authenticated, to the subscribers Real iate,. -

III. Appellate Court Overturns Okubo-Yamada

III. appellate PACIFIC CrrlZEN court overturns Publication of the National Japanese American Citizens League Okubo-Yamada Vol. 86 No. 1 New Year Special: Jan. 6-13, 1978 20¢ Postpaid U.S. 15 Cents STOCKTON, Calif.-It was a go law firm of Baskin, festive Christmas for the Server and Berke. It is "ex Okubo and Yamada families tremely unlikely" the appel here upon hearing from late court would grant Hil their Chicago attorneys just ton Hotel a rehearing at the before the holidays that the appellate level nor receive Jr. Miss Pageant bars alien aspirants lllinois appellate court had permission to appeal to the SEATTLE-Pacific Northwest JACL leaders concede the "It would seem only right and proper that the pageant reversed the Cook County lllinois supreme court, fight to reinstate a 17-year-{)ld Vietnamese girl of Dayton, rules should be amended to include in their qualifications trial court decision and or Berke added. He said! Wash. who was denied the Touchet Valley Junior Miss dered the 1975 civil suit "The end result, after all of pageant candidates the words 'and aliens legally ad aeainst the Hilton Hotel title because she was not an American citizen has most these petitions, is that we are mitted as pennanent residents of the United States'," Ya Corp. to be reheard going to be given amthero~ likely been lost. mamoto wrote in a letter to the Spokane Spokesman Re The Okubo-Yamada case portunity to try this case or The state Junior Miss Pageant will be held at Wenat view. had alleged a breach of ex settle it before trial" chee Jan. -

Henry Wallace Wallace Served Served on On

Papers of HENRY A. WALLACE 1 941-1 945 Accession Numbers: 51~145, 76-23, 77-20 The papers were left at the Commerce Department by Wallace, accessioned by the National Archives and transferred to the Library. This material is ·subject to copyright restrictions under Title 17 of the U.S. Code. Quantity: 41 feet (approximately 82,000 pages) Restrictions : The papers contain material restricted in accordance with Executive Order 12065, and material which _could be used to harass, em barrass or injure living persons has been closed. Related Materials: Papers of Paul Appleby Papers of Mordecai Ezekiel Papers of Gardner Jackson President's Official File President's Personal File President's Secretary's File Papers of Rexford G. Tugwell Henry A. Wallace Papers in the Library of Congress (mi crofi 1m) Henry A. Wallace Papers in University of Iowa (microfilm) '' Copies of the Papers of Henry A. Wallace found at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, the Library of Congress and the University of Iow~ are available on microfilm. An index to the Papers has been published. Pl ease consult the archivist on duty for additional information. I THE UNIVERSITY OF lOWA LIBRAlU ES ' - - ' .·r. .- . -- ........... """"' ': ;. "'l ' i . ,' .l . .·.· :; The Henry A. Wallace Papers :and Related Materials .- - --- · --. ~ '· . -- -- .... - - ·- - ·-- -------- - - Henry A. Walla.ce Papers The principal collection of the papers of (1836-1916), first editor of Wallaces' Farmer; Henry Agard \Vallace is located in the Special his father, H enry Cantwell Wallace ( 1866- Collc:ctions Department of The University of 1924), second editor of the family periodical and Iowa Libraries, Iowa City. \ Val bee was born Secretary of Agriculture ( 1921-192-l:): and his October 7, 1888, on a farm in Adair County, uncle, Daniel Alden Wallace ( 1878-1934), editor Iowa, was graduated from Iowa State University, of- The Farmer, St. -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

Navy and Marine Corps Opposition to the Goldwater Nichols Act of 1986

Navy and Marine Corps Opposition to the Goldwater Nichols Act of 1986 A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Steven T. Wills June 2012 © 2012 Steven T. Wills. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Navy and Marine Corps Opposition to the Goldwtaer Nichols Act of 1986 by STEVEN T. WILLS has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Ingo Traushweizer Assistant Professor of History Howard Dewald Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT WILLS, STEVEN T., M.A., June 2012, History Navy and Marine Corps Opposition to the Goldwater Nichols Act of 1986 Director of Thesis: Ingo Traushweizer The Goldwater Nichols Act of 1986 was the most comprehensive defense reorganization legislation in a generation. It has governed the way the United States has organized, planned, and conducted military operations for the last twenty five years. It passed the Senate and House of Representatives with margins of victory reserved for birthday and holiday resolutions. It is praised throughout the U.S. defense establishment as a universal good. Despite this, it engendered a strong opposition movement organized primarily by Navy Secretary John F. Lehman but also included members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, prominent Senators and Congressman, and President Reagan's Secretary of Defense Casper Weinberger. This essay will examine the forty year background of defense reform movements leading to the Goldwater Nichols Act, the fight from 1982 to 1986 by supporters and opponents of the proposed legislation and its twenty-five year legacy that may not be as positive as the claims made by the Department of Defense suggest. -

Loyalty and Betrayal Reconsidered: the Tule Lake Pilgrimage

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 6-9-2016 "Yes, No, Maybe": Loyalty and Betrayal Reconsidered: The uleT Lake Pilgrimage Ella-Kari Loftfield Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Recommended Citation Loftfield, Ella-Kari. ""Yes, No, Maybe": Loyalty and Betrayal Reconsidered: The uleT Lake Pilgrimage." (2016). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/47 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ella-Kari Loftfield Candidate History Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Professor Melissa Bokovoy, Chairperson Professor Jason Scott Smith Professor Barbara Reyes i “YES, NO, MAYBE−” LOYALTY AND BETRAYAL RECONSIDERED: THE TULE LAKE PILGRIMAGE By Ella-Kari Loftfield B.A., Social Anthropology, Haverford College, 1985 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2016 ii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my father, Robert Loftfield whose enthusiasm for learning and scholarship knew no bounds. iii Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many people. Thanks to Peter Reed who has been by my side and kept me well fed during the entire experience. Thanks to the Japanese American National Museum for inviting me to participate in curriculum writing that lit a fire in my belly. -

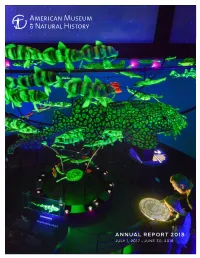

Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 JULY 1, 2017 – JUNE 30, 2018 be out-of-date or reflect the bias and expeditionary initiative, which traveled to SCIENCE stereotypes of past eras, the Museum is Transylvania under Macaulay Curator in endeavoring to address these. Thus, new the Division of Paleontology Mark Norell to 4 interpretation was developed for the “Old study dinosaurs and pterosaurs. The Richard New York” diorama. Similarly, at the request Gilder Graduate School conferred Ph.D. and EDUCATION of Mayor de Blasio’s Commission on Statues Masters of Arts in Teaching degrees, as well 10 and Monuments, the Museum is currently as honorary doctorates on exobiologist developing new interpretive content for the Andrew Knoll and philanthropists David S. EXHIBITION City-owned Theodore Roosevelt statue on and Ruth L. Gottesman. Visitors continued to 12 the Central Park West plaza. flock to the Museum to enjoy the Mummies, Our Senses, and Unseen Oceans exhibitions. Our second big event in fall 2017 was the REPORT OF THE The Gottesman Hall of Planet Earth received CHIEF FINANCIAL announcement of the complete renovation important updates, including a magnificent OFFICER of the long-beloved Gems and Minerals new Climate Change interactive wall. And 14 Halls. The newly named Allison and Roberto farther afield, in Columbus, Ohio, COSI Mignone Halls of Gems and Minerals will opened the new AMNH Dinosaur Gallery, the FINANCIAL showcase the Museum’s dazzling collections first Museum gallery outside of New York STATEMENTS and present the science of our Earth in new City, in an important new partnership. 16 and exciting ways. The Halls will also provide an important physical link to the Gilder All of this is testament to the public’s hunger BOARD OF Center for Science, Education, and Innovation for the kind of science and education the TRUSTEES when that new facility is completed, vastly Museum does, and the critical importance of 18 improving circulation and creating a more the Museum’s role as a trusted guide to the coherent and enjoyable experience, both science-based issues of our time. -

A a C P , I N C

A A C P , I N C . Asian Am erican Curriculum Project Dear Friends; AACP remains concerned about the atmosphere of fear that is being created by national and international events. Our mission of reminding others of the past is as important today as it was 37 years ago when we initiated our project. Your words of encouragement sustain our efforts. Over the past year, we have experienced an exciting growth. We are proud of publishing our new book, In Good Conscience: Supporting Japanese Americans During the Internment, by the Northern California MIS Kansha Project and Shizue Seigel. AACP continues to be active in publishing. We have published thirteen books with three additional books now in development. Our website continues to grow by leaps and bounds thanks to the hard work of Leonard Chan and his diligent staff. We introduce at least five books every month and offer them at a special limited time introductory price to our newsletter subscribers. Find us at AsianAmericanBooks.com. AACP, Inc. continues to attend over 30 events annually, assisting non-profit organizations in their fund raising and providing Asian American book services to many educational organizations. Your contributions help us to provide these services. AACP, Inc. continues to be operated by a dedicated staff of volunteers. We invite you to request our catalogs for distribution to your associates, organizations and educational conferences. All you need do is call us at (650) 375-8286, email [email protected] or write to P.O. Box 1587, San Mateo, CA 94401. There is no cost as long as you allow enough time for normal shipping (four to six weeks). -

2020 NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL Scorecard

2020 NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL scorecard SECOND SESSION OF THE 116TH CONGRESS LCV BOARD OF DIRECTORS * JOHN H. ADAMS, HONORARY RAMPA R. HORMEL, HONORARY BILL ROBERTS Natural Resources Defense Council Enlyst Fund Corridor Partners BRENT BLACKWELDER, HONORARY JOHN HUNTING, HONORARY LARRY ROCKEFELLER Friends of the Earth John Hunting & Associates American Conservation Association THE HONORABLE SHERWOOD L. BOEHLERT, MICHAEL KIESCHNICK THEODORE ROOSEVELT IV, HONORARY VICE CHAIR Green Advocacy Project CHAIR The Accord Group Barclays Capital ROGER KIM THE HONORABLE CAROL BROWNER, CHAIR Democracy Alliance KERRY SCHUMANN Former EPA Administrator Wisconsin Conservation Voters MARK MAGAÑA CARRIE CLARK GreenLatinos LAURA TURNER SEYDEL North Carolina League of Conservation Turner Foundation WINSOME MCINTOSH, HONORARY Voters The McIntosh Foundation TRIP VAN NOPPEN DONNA F. EDWARDS Earthjustice MOLLY MCUSIC Former U.S. Representative Wyss Foundation KATHLEEN WELCH MICHAEL C. FOX Corridor Partners WILLIAM H. MEADOWS III, HONORARY Eloise Capital The Wilderness Society ANTHA WILLIAMS ELAINE FRENCH Bloomberg Philanthropies GREG MOGA John and Elaine French Family Foundation Moga Investments LLC REVEREND LENNOX YEARWOOD, JR. MARIA HANDLEY Hip Hop Caucus REUBEN MUNGER Conservation Colorado Education Fund Vision Ridge Partners, LLC STEVE HOLTZMAN SCOTT NATHAN Boies Schiller Flexner LLP Center for American Progress LCV ISSUES & ACCOUNTABILITY COMMITTEE * BRENT BLACKWELDER SUNITA LEEDS REUBEN MUNGER Friends of the Earth Enfranchisement Foundation Vision Ridge Partners, -

Historic Resource Study

Historic Resource Study Minidoka Internment National Monument _____________________________________________________ Prepared for the National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Seattle, Washington Minidoka Internment National Monument Historic Resource Study Amy Lowe Meger History Department Colorado State University National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Seattle, Washington 2005 Table of Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………… i Note on Terminology………………………………………….…………………..…. ii List of Figures ………………………………………………………………………. iii Part One - Before World War II Chapter One - Introduction - Minidoka Internment National Monument …………... 1 Chapter Two - Life on the Margins - History of Early Idaho………………………… 5 Chapter Three - Gardening in a Desert - Settlement and Development……………… 21 Chapter Four - Legalized Discrimination - Nikkei Before World War II……………. 37 Part Two - World War II Chapter Five- Outcry for Relocation - World War II in America ………….…..…… 65 Chapter Six - A Dust Covered Pseudo City - Camp Construction……………………. 87 Chapter Seven - Camp Minidoka - Evacuation, Relocation, and Incarceration ………105 Part Three - After World War II Chapter Eight - Farm in a Day- Settlement and Development Resume……………… 153 Chapter Nine - Conclusion- Commemoration and Memory………………………….. 163 Appendixes ………………………………………………………………………… 173 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………. 181 Cover: Nikkei working on canal drop at Minidoka, date and photographer unknown, circa 1943. (Minidoka Manuscript Collection, Hagerman Fossil