Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEQUOYA.Ii Constitu'tional Conveifflon 11

THE SEQUOYA.Ii CONSTITu'TIONAL CONVEifflON 11 THE SEQUOYAH CONSTITUTI OKAL CONVE?lTI ON AMOS DeZELL MAX'wELL,, Bachelor or Science Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College Stillwater, Ok1ahana 191+8 Submitted to the Department of History Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College In Part1a1 Fu:l.f'illment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF AR!S 195'0 111 OKLAHOMA '8BICULTUltAL & MlCHANICAL COLLE&I LIBRARY APR 241950 APPROVED Bia ) 250898 iv PREl'.lCE the Sequoy-ah Constitutional. Convention was held 1n Husk-0gee, Indian ferri to17, 1n. the aUBDller of 1905. It was the culminating event of a seriea ot eol.orrul occasions in the history or the .Five Civllized. Tribes. It was there that the deseendanta of those who made the trek west seventy-:f'ive years earlier sat with white men to vr1 te a eharter tor a new state.. They wrote a con st1tution, but it was never used as a charter tor a State or Sequo,yah. This work, which is primarily a stud,y or that convention and tbe reasons for its being called and its results, was undertaken at the suggestion of..,- father, Harold K. Max.well, in August, 1948. It has been carried to a conclusion through the a.id of a number o! persons, chief' among them being my wife, Betty Jo Max well. The need tor this study is a paramount one. Other than copies of the )(Q§koga f!l91P1J, the.re are no known records or the convention. Because much of the proceedings were in one or more Indian tongues there are some gaps in the study other than those due to the laek ot records,. -

PETITION Ror,RECOGNITION of the FLORIDA TRIBE Or EASTERN CREEK INDIANS

'l PETITION rOR,RECOGNITION OF THE FLORIDA TRIBE or EASTERN CREEK INDIANS TH;: FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS and the Administra tive Council, THE NORTHWEST FLORIDA CREEK INDIAN COUNCIL brings this, thew petition to the DEPARTMENT Or THE INTERIOR OF THE FEDERAL GOVERN- MENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, and prays this honorable nation will honor their petition, which is a petition for recognition by this great nation that THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS is an Indian Tribe. In support of this plea for recognition THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS herewith avers: (1) THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS nor any of its members, is the subject of Congressional legislation which has expressly terminated or forbidden the Federal relationship sought. (2) The membership of THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS is composed principally of persons who are not members of any other North American Indian tribe. (3) A list of all known current members of THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEK INDIANS, based on the tribes acceptance of these members and the tribes own defined membership criteria is attached to this petition and made a part of it. SEE APPENDIX----- A The membership consists of individuals who are descendants of the CREEK NATION which existed in aboriginal times, using and occuping this present georgraphical location alone, and in conjunction with other people since that time. - l - MNF-PFD-V001-D0002 Page 1of4 (4) Attached herewith and made a part of this petition is the present governing Constitution of THE FLORIDA TRIBE OF EASTERN CREEKS INDIANS. -

Friends of the Capitol 2009-June 2010 Report

Friends of the Capitol 2009-June 2010 Report Our Mission Statement: Friends of the Capitol is a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) corporation that is devoted to maintaining and improving the beauty and grandeur of the Oklahoma State Capitol building and showcasing the magnificent gifts of art housed inside. This mission is accomplished through a partnership with private citizens wishing to leave their footprint in our state's rich history. Education and Development In 2009 and 2010 Friends of the Capitol (FOC) participated in several educational and developmental projects informing fellow Oklahomans of the beauty of the capitol and how they can participate in the continuing renovations of Oklahoma State Capitol building. In March of 2010, FOC representatives made a trip to Elk City and met with several organizations within the community and illustrated all the new renovations funded by Friends of the Capitol supporters. Additionally in 2009 FOC participated in the State Superintendent’s encyclo-media conference and in February 2010 FOC participated in the Oklahoma City Public Schools’ Professional Development Day. We had the opportunity to meet with teachers from several different communities in Oklahoma, and we were pleased to inform them about all the new restorations and how their school’s name can be engraved on a 15”x30”paver, and placed below the Capitol’s south steps in the Centennial Memorial Plaza to be admired by many generations of Oklahomans. Gratefully Acknowledging the Friends of the Capitol Board of Directors Board Members Ex-Officio Paul B. Meyer, Col. John Richard Chairman USA (Ret.) MA+ Architecture Oklahoma Department Oklahoma City of Central Services Pat Foster, Vice Chairman Suzanne Tate Jim Thorpe Association Inc. -

A Reserved Right Does Not Make a Wrong

Tulsa Law Review Volume 48 Issue 2 Winter 2012 A Reserved Right Does Not Make a Wrong Wyatt M. Cox Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Wyatt M. Cox, A Reserved Right Does Not Make a Wrong, 48 Tulsa L. Rev. 373 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol48/iss2/20 This Casenote/Comment is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Law Review by an authorized editor of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cox: A Reserved Right Does Not Make a Wrong A RESERVED RIGHT DOES NOT MAKE A WRONG 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................. 374 II. TREATIES WITH THE TRIBAL NATIONS ............................................. 375 A. The Canons of Construction. ........................... ...... 375 B. The Power and Purpose of the Indian Treaty ............................... 376 C. The Equal Footing Doctrine .............................................377 D. A Brief Overview of the Policy History of Treaties ............ ........... 378 E. The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.........................380 III. THE ESTABLISHMENT AND EXPANSION OF THE INDIAN RESERVED WATER RIGHT ....381 A. Winters v. United States: The Establishment of Reserved Indian Water Rights...................................................382 B. Arizona v. California:Not Only Enough Water to Fulfill the Purposes of Today, but Enough to Fulfill the Purposes of Forever ...................... 383 C. Cappaertv. United States: The Supreme Court Further Expands the Winters Doctrine ........................................ 384 IV. Two OKLAHOMA CASES THAT SUPPORT THE TRIBAL NATION CLAIMS .................... 385 A. Choctaw Nation v. Oklahoma (The Arkansas River Bank Case) .................. -

The Riff Issue

STOCKHOLM WOW AUTUMN CITIES: LONDON, P The riff issue : COPENHA ARIS, BERLIN, WE ARE ON OUR WAY! T he future of of he future GEN I celandic cinema is in the air THE RIFF ISSUE The future of Icelandic cinema What is RIFF? Learn all there is to know about Reykjavík International Film Festival WOW PICKS The must-see list at RIFF What’s going on? Iceland is happening IS IN THE AIR I ssue five Winter is coming: ISSUE 2013 GET YOUR GEAR READY FOR FIVE 2013 THESE AWESOME PISTES Tax & Duty Free Experience Iceland All of our shops and restaurants offer you Icelandic memories to take home. /SIA.IS/FLE 63311 04/13 ÍSLENSKA One of few airports in the world that is both tax and duty free — meaning up to 50% off city prices. Nearby Landmannalaugar 2 ı WOW is in the air TaxTax && DutyDuty FreeFree ExperienceExperience IcelandIceland AllAll ofof ourour shopsshops andand restaurantsrestaurants offeroffer youyou IcelandicIcelandic memoriesmemories toto taketake home.home. /SIA.IS/FLE 63311 04/13 /SIA.IS/FLE 63311 04/13 ÍSLENSKA ÍSLENSKA OneOne ofof fewfew airportsairports inin thethe worldworld thatthat isis bothboth taxtax andand dutyduty freefree —— meaningmeaning upup toto 50%50% offoff citycity prices.prices. NearbyNearby LandmannalaugarLandmannalaugar Issue five ı 3 Hello darkness my old friend … The fall is a time for contemplation and, at least in my case, a new beginning. It’s about getting the kids back to school, wiping the frost from the car windows, rejoicing in the autumn colors and dreading but still kind of looking forward to the darkest days of winter. -

Choctaw and Creek Removals

Chapter 6 Choctaw and Creek Removals The idea of indian removal as a government obligation first reared its head in 1802 when officials of the state of Georgia made an agreement with federal government officials. In the Georgia Compact, the state of Georgia gave up its claims to territorial lands west of that state in exchange for $1,250,000 and a promise that the federal government would abolish Indian title to Georgia lands as soon as possible. How seriously the government took its obligation to Georgia at the time of the agreement is unknown. The following year, however, the Louisiana Purchase was made, and almost immedi- ately, the trans-Mississippi area was seen by some as the answer to “The Indian Problem.” Not everyone agreed. Some congress- men argued that removal to the West was impractical because of land-hungry whites who could not be restrained from crossing the mighty river to obtain land. Although their conclusion was correct, it was probably made more in opposition to President Jefferson than from any real con- cern about the Indians or about practicality. Although some offers were made by government officials to officials of various tribes, little Pushmataha, Choctaw was done about removing the southeastern tribes before the War of 1812. warrior During that war several Indian tribes supported the British. After the war ended, many whites demanded that tribal lands be confiscated by Removals 67 the government as punishment for Indians’ treasonous activities. Many Americans included all tribes in their confiscationdemands , evidently feeling that all Indians were guilty, despite the fact that many tribes did not participate in the war. -

Fort King National Historic Landmark Education Guide 1 Fig5

Ai-'; ~,,111m11l111nO FORTKINO NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK Fig1 EDUCATION GUIDE This guide was made possible by the City of Ocala Florida and the Florida Department of State/Division of Historic Resources WELCOME TO Micanopy WE ARE EXCITED THAT YOU HAVE CHOSEN Fort King National Historic Fig2 Landmark as an education destination to shed light on the importance of this site and its place within the Seminole War. This Education Guide will give you some tools to further educate before and after your visit to the park. The guide gives an overview of the history associated with Fort King, provides comprehension questions, and delivers activities to Gen. Thomas Jesup incorporate into the classroom. We hope that this resource will further Fig3 enrich your educational experience. To make your experience more enjoyable we have included a list of items: • Check in with our Park Staff prior to your scheduled visit to confrm your arrival time and participation numbers. • The experience at Fort King includes outside activities. Please remember the following: » Prior to coming make staff aware of any mobility issues or special needs that your group may have. » Be prepared for the elements. Sunscreen, rain gear, insect repellent and water are recommended. » Wear appropriate footwear. Flip fops or open toed shoes are not recommended. » Please bring lunch or snacks if you would like to picnic at the park before or after your visit. • Be respectful of our park staff, volunteers, and other visitors by being on time. Abraham • Visitors will be exposed to different cultures and subject matter Fig4 that may be diffcult at times. -

Kevin E. Dudley, Et Al.; Town of Fort Gibson, Oklahoma

INTERIOR BOARD OF INDIAN APPEALS Alan Chapman; Kevin E. Dudley, et al.; Town of Fort Gibson, Oklahoma; Muskogee County, Oklahoma; Oklahoma Tax Commission; Harold Wade; Quik Trip, Inc., et al.; City of Catoosa, Oklahoma v. Muskogee Area Director, Bureau of Indian Affairs 32 IBIA 101 (03/13/1998) Related Board case: 35 IBIA 285 United States Department of the Interior OFFICE OF HEARINGS AND APPEALS INTERIOR BOARD OF INDIAN APPEALS 4015 WILSON BOULEVARD ARLINGTON, VA 22203 ALAN CHAPMAN, : Order Lifting Stay, Vacating Appellant : Decisions, and Remanding KEVIN E. DUDLEY, et al., : Cases Appellants : TOWN OF FORT GIBSON, OKLAHOMA, : Appellant : MUSKOGEE COUNTY, OKLAHOMA, : COMMISSIONERS, : Appellants : ALAN CHAPMAN, : Appellant : KEVIN E. DUDLEY, et al., : Docket No. IBIA 96-115-A Appellants : Docket No. IBIA 96-119-A OKLAHOMA TAX COMMISSION, : Docket No. IBIA 96-122-A Appellant : Docket No. IBIA 96-123-A OKLAHOMA TAX COMMISSION, : Docket No. IBIA 96-124-A Appellant : Docket No. IBIA 96-125-A HAROLD WADE, : Docket No. IBIA 97-2-A Appellant : Docket No. IBIA 97-3-A OKLAHOMA TAX COMMISSION, : Docket No. IBIA 97-10-A Appellant : Docket No. IBIA 97-11-A QUIK TRIP, INC., et al., : Docket No. IBIA 97-12-A Appellants : Docket No. IBIA 97-14-A OKLAHOMA TAX COMMISSION, : Docket No. IBIA 97-40-A Appellant : CITY OF CATOOSA, OKLAHOMA : Appellant : : v. : : MUSKOGEE AREA DIRECTOR, : BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS, : Appellee : March 13, 1998 32 IBIA 101 These are consolidated appeals from four decisions of the Muskogee Area Director, Bureau of Indian Affairs, to take certain tracts of land into trust. -

Challenge Bowl 2020

Notice: study guide will be updated after the December general election. Sponsored by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Challenge Bowl 2020 High School Study Guide Sponsored by the Challenge Bowl 2020 Muscogee (Creek) Nation Table of Contents A Struggle To Survive ................................................................................................................................ 3-4 1. Muscogee History ......................................................................................................... 5-30 2. Muscogee Forced Removal ........................................................................................... 31-50 3. Muscogee Customs & Traditions .................................................................................. 51-62 4. Branches of Government .............................................................................................. 63-76 5. Muscogee Royalty ........................................................................................................ 77-79 6. Muscogee (Creek) Nation Seal ...................................................................................... 80-81 7. Belvin Hill Scholarship .................................................................................................. 82-83 8. Wilbur Chebon Gouge Honors Team ............................................................................. 84-85 9. Chronicles of Oklahoma ............................................................................................... 86-97 10. Legends & Stories ...................................................................................................... -

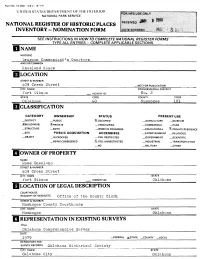

HCLASSIFI C ATI ON

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES •m^i:':^Mi:iMmm:mm-mmm^mmmmm:M;i:!m::::i!:- INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM 1 SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ [NAME HISTORIC Dragoon Commandant's Quarters_____________________________________ AND/OR COMMON Kneeland House________________________________________ LOCATION STREET & NUMBER /f09 Creek Street —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Fort Gibs on _. VICINITY OF No. 2. STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Oklahoma uo Muskogee 101 HCLASSIFI c ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC ^OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM JSBUILDING(S) X.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL ?_PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT __|N PROCESS —YES. RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL _ TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Ross Kneeland STREETS. NUMBER Creek Street CITY. TOWN STATE Fort Gibson VICINITY OF Oklahoma LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDs.ETC. Office of the County Clerk STREET & NUMBER Muskogee County Courthouse CITY, TOWN STATE Muskogee Oklahoma REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Oklahoma Comprehensive Survey DATE 1979 —FEDERAL X-STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Oklahoma Historical Society CITY. TOWN STATE Oklahoma City Oklahoma DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE XGOOD —RUINS .^ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Paint and a modern composition roof tend to disguise the age of the Dragoon Commandant's Quarters. -

Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842 Toni Carrier University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Carrier, Toni, "Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842" (2005). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2811 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842 by Toni Carrier A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Brent R. Weisman, Ph.D. Robert H. Tykot, Ph.D. Trevor R. Purcell, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 14, 2005 Keywords: Social Capital, Political Economy, Black Seminoles, Illicit Trade, Slaves, Ranchos, Wreckers, Slave Resistance, Free Blacks, Indian Wars, Indian Negroes, Maroons © Copyright 2005, Toni Carrier Dedication To my baby sister Heather, 1987-2001. You were my heart, which now has wings. Acknowledgments I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to the many people who mentored, guided, supported and otherwise put up with me throughout the preparation of this manuscript. To Dr. -

Challenge Bowl 2020

Sponsored by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Challenge Bowl 2020 High School Study Guide Sponsored by the Challenge Bowl 2020 Muscogee (Creek) Nation Table of Contents A Struggle To Survive ................................................................................................................................ 3-4 1. Muscogee History ......................................................................................................... 5-30 2. Muscogee Forced Removal ........................................................................................... 31-50 3. Muscogee Customs & Traditions .................................................................................. 51-62 4. Branches of Government .............................................................................................. 63-76 5. Muscogee Royalty ........................................................................................................ 77-79 6. Muscogee (Creek) Nation Seal ...................................................................................... 80-81 7. Belvin Hill Scholarship .................................................................................................. 82-83 8. Wilbur Chebon Gouge Honors Team ............................................................................. 84-85 9. Chronicles of Oklahoma ............................................................................................... 86-97 10. Legends & Stories ......................................................................................................