Foreign Exchange Hedging in Chile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Establishing Credibility: the Role of Foreign Advisors in Chile's 1955

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: The Decline of Latin American Economies: Growth, Institutions, and Crises Volume Author/Editor: Sebastian Edwards, Gerardo Esquivel and Graciela Márquez, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-18500-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/edwa04-1 Conference Date: December 2-4, 2004 Publication Date: July 2007 Title: Establishing Credibility: The Role of Foreign Advisors in Chile’s 1955–1958 Stabilization Program Author: Sebastian Edwards URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c10659 8 Establishing Credibility The Role of Foreign Advisors in Chile’s 1955–1958 Stabilization Program Sebastian Edwards 8.1 Introduction The adoption of stabilization programs is usually a painful process, both politically and economically. History is replete with instances where, even in the light of obvious and flagrant macroeconomics disequilibria, the implementation of stabilization programs is significantly delayed. Why do policymakers and/or politicians prefer to live with growing inflationary pressures and implement price and other forms of highly inefficient con- trols instead of tackling the roots of macroeconomic imbalances? Is the prolongation of inflation the consequence of mistaken views on the me- chanics of fiscal deficits and money creation, or is it the unavoidable result of the political game? Why, after months of apparent political stalemate, are stabilization programs all of a sudden adopted that closely resemble others proposed earlier? These questions are at the heart of the political economy of stabilization and inflationary finance.1 In recent years the analysis of these issues has attained new interest, as a number of authors have applied the tools of game theory to the study of macroeconomic pol- icymaking. -

Black Market Peso Exchange As a Mechanism to Place Substantial Amounts of Currency from U.S

United States Department of the Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network FinCEN Advisory Subject: This advisory is provided to alert banks and other depository institutions Colombian to a large-scale, complex money laundering system being used extensively by Black Market Colombian drug cartels to launder the proceeds of narcotics sales. This Peso Exchange system is affecting both U.S. financial depository institutions and many U.S. businesses. The information contained in this advisory is intended to help explain how this money laundering system works so that U.S. financial institutions and businesses can take steps to help law enforcement counter it. Overview Date: November Drug sales in the United States are estimated by the Office of National 1997 Drug Control Policy to generate $57.3 billion annually, and most of these transactions are in cash. Through concerted efforts by the Congress and the Executive branch, laws and regulatory actions have made the movement of this cash a significant problem for the drug cartels. America’s banks have effective systems to report large cash transactions and report suspicious or Advisory: unusual activity to appropriate authorities. As a result of these successes, the Issue 9 placement of large amounts of cash into U.S. financial institutions has created vulnerabilities for the drug organizations and cartels. Efforts to avoid report- ing requirements by structuring transactions at levels well below the $10,000 limit or camouflage the proceeds in otherwise legitimate activity are continu- ing. Drug cartels are also being forced to devise creative ways to smuggle the cash out of the country. This advisory discusses a primary money laundering system used by Colombian drug cartels. -

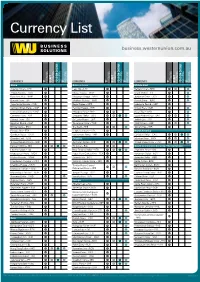

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Cepal Review 82

LC/G.2220-P — April 2004 United Nations Publication ISBN 92-1-121537-4 ISSN printed version 0251-2920 ISSN online version 1684-0348 c e p a l R eview is prepared by the Secretariat of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. The views expressed in the signed articles, including the contributions of Secretariat staff members, however, represent the personal opinion of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Organization. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. c e p a l Review is published in Spanish and English versions three times a year. Annual subscription costs for 2004 are US$ 30 for the Spanish version and US$ 35 for the English version. The price of single issues is US$ 15 in both cases, plus postage and packing. The cost of a two-year subscription (2004-2005) is US$ 50 for the Spanish-language version and US$ 60 for English. A subscription application form may be found just before the section “Recent e c l a c Publications”. Applications for the right to reproduce this work or parts thereof are welcomed and should be sent to the Secretary of the Publications Board, United Nations Headquarters, New York, N.Y. 10017, U.S.A. Member States and their governmental institutions may reproduce this work without application, but are requested to mention the source and inform the United Nations of such reproduction. -

List of Certain Foreign Institutions Classified As Official for Purposes of Reporting on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms

NOT FOR PUBLICATION DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY JANUARY 2001 Revised Aug. 2002, May 2004, May 2005, May/July 2006, June 2007 List of Certain Foreign Institutions classified as Official for Purposes of Reporting on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms The attached list of foreign institutions, which conform to the definition of foreign official institutions on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms, supersedes all previous lists. The definition of foreign official institutions is: "FOREIGN OFFICIAL INSTITUTIONS (FOI) include the following: 1. Treasuries, including ministries of finance, or corresponding departments of national governments; central banks, including all departments thereof; stabilization funds, including official exchange control offices or other government exchange authorities; and diplomatic and consular establishments and other departments and agencies of national governments. 2. International and regional organizations. 3. Banks, corporations, or other agencies (including development banks and other institutions that are majority-owned by central governments) that are fiscal agents of national governments and perform activities similar to those of a treasury, central bank, stabilization fund, or exchange control authority." Although the attached list includes the major foreign official institutions which have come to the attention of the Federal Reserve Banks and the Department of the Treasury, it does not purport to be exhaustive. Whenever a question arises whether or not an institution should, in accordance with the instructions on the TIC forms, be classified as official, the Federal Reserve Bank with which you file reports should be consulted. It should be noted that the list does not in every case include all alternative names applying to the same institution. -

Colombian Peso Forecast Special Edition Nov

Friday Nov. 4, 2016 Nov. 4, 2016 Mexican Peso Outlook Is Bleak With or Without Trump Buyside View By George Lei, Bloomberg First Word The peso may look historically very cheap, but weak fundamentals will probably prevent "We're increasingly much appreciation, regardless of who wins the U.S. election. concerned about the The embattled currency hit a three-week low Nov. 1 after a poll showed Republican difference between PDVSA candidate Donald Trump narrowly ahead a week before the vote. A Trump victory and Venezuela. There's a could further bruise the peso, but Hillary Clinton wouldn't do much to reverse 26 scenario where PDVSA percent undervaluation of the real effective exchange rate compared to the 20-year average. doesn't get paid as much as The combination of lower oil prices, falling domestic crude production, tepid economic Venezuela." growth and a rising debt-to-GDP ratio are key challenges Mexico must address, even if — Robert Koenigsberger, CIO at Gramercy a status quo in U.S. trade relations is preserved. Oil and related revenues contribute to Funds Management about one third of Mexico's budget and output is at a 32-year low. Economic growth is forecast at 2.07 percent in 2016 and 2.26 percent in 2017, according to a Nov. 1 central bank survey. This is lower than potential GDP growth, What to Watch generally considered at or slightly below 3 percent. To make matters worse, Central Banks Deputy Governor Manuel Sanchez said Oct. Nov. 9: Mexico's CPI 21 that the GDP outlook has downside risks and that the government must urgently Nov. -

Argentina's 2001 Economic and Financial Crisis: Lessons for Europe

Argentina’s 2001 economic and Financial Crisis: Lessons for europe Former Under Secretary of Finance and Chief Advisor to the Minister of the Miguel Kiguel Economy, Argentina; Former President, Banco Hipotecario; Director, Econviews; Professor, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella he 2001 Argentine economic and financial banks and international reserves—was not enough crisis has many parallels with the problems to cover the financial liabilities of the consolidated Tthat some European countries are facing to- financial system . This was a major source of vulner- day . Prior to the crisis, Argentina was suffering a ability, especially because there is ample evidence deep recession, large levels of debt, twin deficits in that an economy without a lender of last resort is the fiscal and current accounts, and the country inherently unstable and subject to bank runs . This had an overvalued currency but devaluation was is not a pressing issue in Europe, where the Euro- not an option . pean Central Bank can provide liquidity to banks . Argentina tried in vain to restore its competitive- The trigger for the crisis in Argentina was a run on ness through domestic deflation and improving the banking system as people realized that there its solvency by increasing its fiscal accounts in were not enough dollars in the system to cover all the midst of a recession . The country also tried to the deposits . As the run intensified, the Argentine avoid a default first by resorting to a large financial government was forced to introduce a so-called package from the multilateral institutions (the so “fence” to control the outflow of deposits . -

Annual Report 2008

Annual Report 2008 WorldReginfo - 5f1ce261-c299-463d-994c-4e559b2c3833 Our Mission 01 Chairman’s Letter 02 Historical Outline 04 Contents Corporate Governance and Capital Structure 06 Board of Directors 08 Corporate Governance Practices 12 Ownership of Banco de Chile 20 Banco de Chile Share 22 Economic and Financial Environment 26 Economic Environment 28 Chilean Financial System 32 Performance in 2008 36 Chief Executive Officer Report 38 Our Management 44 Principal Indicators 45 Highlights 2008 46 Results Analysis 48 Business Areas 54 Business Areas of Banco de Chile 56 Individuals and Middle Market Companies 58 Banco CrediChile 60 Wholesale, Large Companies and Real Estate 62 Corporate and Investments 66 Subsidiaries 70 Risk Management 74 Credit Risk 78 Financial Risk 85 Operational Risk 96 Social Responsibility 100 Our Staff 102 Our Community 110 Our Customers 118 Consolidated Financial Statements 120 WorldReginfo - 5f1ce261-c299-463d-994c-4e559b2c3833 Our Mission We are a leading financial corporation with a prestigious business tradition. Our call purpose is to provide financial services of excellence, offering creative and effective solutions for each customer segment and thus ensuring permanent value growth for our shareholders. Our Vision To be the best bank for our customers, the best place to work and the best investment for our shareholders. WorldReginfo - 5f1ce261-c299-463d-994c-4e559b2c3833 Chairman’s Letter Dear Shareholders, It is a particular pleasure for me to present you the annual report and with Citigroup. In particular, I emphasize the international services financial statements for the year 2008, a period in which we agreed provided to corporate and multinational customers, the wide range the absorption of Citibank Chile’s business and began a momentous of treasury products available to companies and a superior presence strategic alliance with Citigroup Inc. -

Macroeconomic Situation Food Prices and Consumption

Dr. Eugenia Muchnik, Manager Agroindustrial Dept., Fundacion Chile, Santiago, Chile Loreto Infante, Agricultural Economist, Assistant CHILE Tomas Borzutzky; Agricultural Economist, Agroindustrial Dept., Fundacion Chile Macroeconomic Situation price index had a -1 percent reduction. Inflation rates and food price fter 2000, in which the Chilean economy exhibited increases are not expected to differ much during 2003 unless there are an encouraging growth rate of 5.4 percent, 2001 unexpected external shocks. The proximity of Argentina and the showed a slowdown, reaching a rate of 2.8 percent, reduction of its export prices as a result of a drastic devaluation may in with growth led by fisheries and energy. Agricultural fact result in price reductions; prices of agricultural inputs have been AGDP grew by 4.7 percent, double the average growth declining, while there are no reasons to expect important changes in rate for the economy as a whole. On the low end of the spectrum, the Chilean real exchange rate. manufacturing experienced a negative growth of -0.3 percent, and in general, the slowest economic growth took place in sectors more dependent on the behavior of domestic demand. There were two Food Processing and Marketing events that took place in the second half of 2001 that changed the At present, the most dynamic sectors in the food processing industry external scenario of the global economy, increasing uncertainty in are wine production and the manufacture of meats and dairy products. financial markets and reducing global growth: the terrorist attacks of In the wine industry, as a result of the rapid expansion of vineyard September 11 and the rapid deterioration of Argentina’s economy. -

Chile: a Macroeconomic Analysis Lee Moore Jose Stevenson Rico X

Chile: A Macroeconomic Analysis Lee Moore Jose Stevenson Rico X I. Chile: A Macroeconomic Success Story In the last decade, Chile has gained a reputation as one of the most stable economies in Latin America. It has implemented a set of fiscal and monetary policies that encourage privatization, focus on exports, encourage high levels of foreign trade and generally promote stabilization. These policies seem to have worked very well for the country, evidenced by steady and sometimes very high growth rates. From 1985-2000, GDP growth averaged 6.6%. Chile is also famous for its privatized pension system, which has been a model for other Latin American countries, and countries around the world. Workers invest their pensions in domestic markets, which has added roughly $36 billion into the economy, a significant source of investment capital for the stock market.1 Chile experienced a slight recession in 1998-99, due to shocks from the Asian financial crisis of 1997. With increasing unemployment and inflation rates, Chile struggled to maintain its policy of keeping the peso fixed to the US dollar within a band width of 25%.2 In September of 1999, Chile let its peso float, increasing its leeway in monetary policy decisions. Below is a brief history of the macroeconomic indicators, leading up to and beyond the floatation policy, which played a significant role in shaping Chile’s recent economy. Figure 1: Chile’s Real GDP (’96-01) II. Recent Macroeconomic Performance Chile's Real GDP GDP: After a steadily increasing GDP throughout the 80’s and 90’s, Chile’s GDP 37,000,000 36,000,000 growth took a downward turn by –1.1% in 35,000,000 3 34,000,000 1999. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

2008 Annual Report

2008 ANNUAL REPORT “I HAVE BEEN A LOYAL CUSTOMER FOR OVER 40 YEARS” “TODAY OUR CLINIC GROWS WITH THE SUPPORT OF A “WITH CORPBANCA’S SUPPORT WE BANK THAT WILL BE ABLE TO ACTIVELY TRUSTS ITS PARTICIPATE IN OUR COUNTRY’S CUSTOMERS” DEVELOPMENT” “A RELATIONSHIP BUILT ON TRUST WILL ACHIEVE SUCCESS” “CORPBANCA HAS BEEN A GUIDING FORCE BEHIND MY COMPANY’S DEVELOPMENT” “THE CONTINUED SUPPORT OF THE BANK HAS PERMITTED US TO MOVE FORWARD WITH MAJOR COMMITMENTS IN CHILE “WITH CORPBANCA’S AND ABROAD” CONTINUED SUPPORT WE HAVE OPENED NEW PATHS GOING FORWARD” “I CAN NOW PROUDLY CALL MYSELF A HOMEOWNER” 2008 ANNUAL REPORT INDEX 6 LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN 10 HISTORY 14 2008 HIGHLIGHTS 18 COMPANY VALUES 20 COMMITMENTS 22 CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY 26 PLAN FOR A HEALTHY LIFE 28 COMMUNICATIONS STRATEGY 30 FLIGHT TO 2011 QUALITY TALENT CULTURE 32 COMPANY INFORMATION 34 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 36 SHAREHOLDERS 38 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 68 RISK MANAGEMENT DIRECTORS COMMITTEE COMPANIES CREDIT RISK AUDIT COMMITTEE COMMERCIAL RISK ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING AND ANTI- FINANCIAL RISK TERRORISM FINANCE PREVENTION COMMITTEE OPERATIONAL RISK COMPLIANCE COMMITTEE COMPTROLLER 76 DISTRIBUTION OF EARNINGS AND DIVIDEND POLICY OFFICE OF THE COMPTROLLER CODE OF CONDUCT AND MARKET INFORMATION MANUAL 78 INVESTMENT AND FINANCING POLICIES 82 NEW YORK BRANCH AND INTERNATIONAL CONDITIONS 42 MANAGEMENT MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE AND 86 PRINCIPAL ASSETS PERSONNEL COMPENSATION 92 RELATED COMPANIES 46 FINANCIAL SUMMARY CORPCAPITAL CORREDORES DE BOLSA S.A. CORPBANCA CORREDORES DE SEGUROS S.A. 48 ECONOMIC CONDITIONS CORPCAPITAL ADMINISTRADORA GENERAL DE FONDOS S.A. CORPCAPITAL ASESORÍAS FINANCIERAS S.A. 50 RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE BANKING INDUSTRY CORPLEGAL S.A.