A Brief History of Brent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

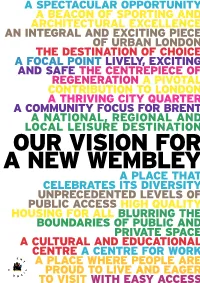

VISION for WEMBLEY the New Wembley: Key Components

A SPECTACULAR OPPORTUNITY A BEACON OF SPORTING AND ARCHITECTURAL EXCELLENCE AN INTEGRAL AND EXCITING PIECE OF URBAN LONDON THE DESTINATION OF CHOICE A FOCAL POINT LIVELY, EXCITING AND SAFE THE CENTREPIECE OF REGENERATION A PIVOTAL CONTRIBUTION TO LONDON A THRIVING CITY QUARTER A COMMUNITY FOCUS FOR BRENT A NATIONAL, REGIONAL AND LOCAL LEISURE DESTINATION OUR VISION FOR A NEW WEMBLEY A PLACE THAT CELEBRATES ITS DIVERSITY UNPRECEDENTED LEVELS OF PUBLIC ACCESS HIGH QUALITY HOUSING FOR ALL BLURRING THE BOUNDARIES OF PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SPACE A CULTURAL AND EDUCATIONAL CENTRE A CENTRE FOR WORK A PLACE WHERE PEOPLE ARE PROUD TO LIVE AND EAGER TO VISIT WITH EASY ACCESS foreword The regeneration of Wembley is central to Brent Council’s aspirations for the borough. We are determined that Wembley becomes a place of which the people of London and Brent can be truly proud. The new Wembley’s varied and high quality facilities will attract millions of visitors from across the country and beyond and will stimulate jobs and wealth across West London. Wembley will make an even greater contribution to London’s status as a World City. Brent Council’s commitment to Wembley is a long-standing one. We have fought long and hard over many years to secure the National Stadium and we have been a pivotal and influential partner throughout this process. We are now determined to maximise the National Stadium’s impact as a catalyst for regeneration and are ready to seize this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to regenerate the area. We are proud that the nation’s new stadium has come to Brent and grateful to all those who have helped make this a reality. -

Re Curriculum for Hinduism

“The Mandir is so welcoming and it is a real highlight of the year. I will be sure to be booking again for next year.” RE Teacher, Holmewood House Prep School, Kent ENHANCING YOUR RE CURRICULUM FOR HINDUISM KS1 KS2 KS3 KS4 The ‘Neasden Temple’Temple’ in north-west London is a beautiful “It was the best school trip and inspiring place of learning for tens of thousands of we have been on so far.” Year 5, Maple Grove experience of Hinduism as a part of their Religious Primary School, Essex Education curriculum for KS1, KS2, KS3 and KS4. FREE Temple Entry ‘Understanding Hinduism’ Exhibition: £1.50 per student BOOK A VISIT Book your school’s visit using our online form at londonmandir.baps.org/visit-us/booking-form For enquiries, please email [email protected] For more information, please visit londonmandir.baps.org/visit-us/school-visits A typical educational visit can include: • witnessing a traditional Hindu ceremony CONTACT US • worksheets tailored for various age groups BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir • an interactive presentation about key Hindu beliefs, What better place to learn about Neasden, London NW10 8LD, UK practices and values Hinduism than in the country’s 020 8965 2651 • an 11-minute documentary on how the temple was built [email protected] largest traditional Hindu temple? • ‘Understanding Hinduism’ exhibition where you discover londonmandir.baps.org the origins and development of the world’s oldest living faith @neasdentemple “The organisation and general experience could not have been better. The children gained knowledge of Hinduism that could not have been achieved in the classroom.” RE Teacher, Brill Church of England School, Buckinghamshire “Largest traditional built Mandir in the world”. -

Neighbourhoods in England Rated E for Green Space, Friends of The

Neighbourhoods in England rated E for Green Space, Friends of the Earth, September 2020 Neighbourhood_Name Local_authority Marsh Barn & Widewater Adur Wick & Toddington Arun Littlehampton West and River Arun Bognor Regis Central Arun Kirkby Central Ashfield Washford & Stanhope Ashford Becontree Heath Barking and Dagenham Becontree West Barking and Dagenham Barking Central Barking and Dagenham Goresbrook & Scrattons Farm Barking and Dagenham Creekmouth & Barking Riverside Barking and Dagenham Gascoigne Estate & Roding Riverside Barking and Dagenham Becontree North Barking and Dagenham New Barnet West Barnet Woodside Park Barnet Edgware Central Barnet North Finchley Barnet Colney Hatch Barnet Grahame Park Barnet East Finchley Barnet Colindale Barnet Hendon Central Barnet Golders Green North Barnet Brent Cross & Staples Corner Barnet Cudworth Village Barnsley Abbotsmead & Salthouse Barrow-in-Furness Barrow Central Barrow-in-Furness Basildon Central & Pipps Hill Basildon Laindon Central Basildon Eversley Basildon Barstable Basildon Popley Basingstoke and Deane Winklebury & Rooksdown Basingstoke and Deane Oldfield Park West Bath and North East Somerset Odd Down Bath and North East Somerset Harpur Bedford Castle & Kingsway Bedford Queens Park Bedford Kempston West & South Bedford South Thamesmead Bexley Belvedere & Lessness Heath Bexley Erith East Bexley Lesnes Abbey Bexley Slade Green & Crayford Marshes Bexley Lesney Farm & Colyers East Bexley Old Oscott Birmingham Perry Beeches East Birmingham Castle Vale Birmingham Birchfield East Birmingham -

( BRONDESBL"RY ). Tooley Charlotte (Mrs.), Fruiterer, 84 Barley Road

DIRECTORY.] :MIDDLESEX. WILLESDE~ ( BRONDESBL"RY ). 395 Tooley Charlotte (Mrs.), fruiterer, 84 Barley road Webster William, harness maker, 66 High street Totternhoe Lime, Stone & Cement Co. Limited, lime & \NP.lford & Sons Limited (established I845); chief office cement merchants, Station road & working dairy, Townsend Florence & .Ada (Misses), baby linen warehouse Elgin avenue, Maida & ladies' outfitters, 24 High street Vale W; model dwell Tracey John, china & glass dealer, see Blizard & Tracey ings for employes, I, Tredwell Henry Thomas, goods agent L. & );. W. Hail- 2 & 3 blocks, Shirland way goods station, Station road roat1. W ; u1enl'il de Tudor & Jenks, general drapers, Bank buildings, High st rarttprnt, Gatehouse, Turner Kate (Miss), school for girls, 32 Green Hill road Shirland road W ; Turner William .A. grocer & provision dealer, I02 High st oranch dairies in all Tustin Thomas King, dining rooms, 1 I3 High street J arts of London. Tyrrell Brothers, fruiterers &c. 87 High street · Dairy l:'arm,Haycroft Underwood Mary (Mrs.), shopkeeper & dairy, 45 Railway F1nm, Harlesden rd. cottages, Willesden Junction Willesden N W ; tele- UnderwO'Od Thomas, 'dairyman, :;g Station road & EM S DWELLlN(iS. grams, "Welfords, United Collieries Co. (The), Slionebridge Park depot, London"; telephone No. 107 Paddington Craven park Wells Henry, oil & calor man, 156 Manor Park road United Kingdom Railway Temperance Union (George West Middlesex Water Works Co. District Office (Horace Lascelles, sec.), 91 Railway cots. Willesden Junction Freest one, inspector}, So Tubbs road Velvin Leonard, milliner, 48 Craven Pa,rk road White Brice, fruiterer &c. I6 High st. & 25 Station rd Venn Bros. hosiers & hatters 17, & clothiers rg, High st White Jas. -

Make the Most of Your Membership by Using the Social Spaces and Attending Events Across All London Chapters January–April 2019

YOUR JANUARY–APRIL 2019 SEMESTER TWO MAKE THE MOST OF YOUR MEMBERSHIP BY USING THE SOCIAL SPACES AND ATTENDING EVENTS ACROSS ALL LONDON CHAPTERS CHAPTER KINGS CROSS “I made loads of friends who live here, the location is great and the staff are great too.” Franciscan from Spain Kings College London TO YOUR SEMESTER TWO EVENT GUIDE. CHAPTER HIGHBURY “It’s really good to have a gym and s you know, being a member cinema in my building.” of Chapter means you have Kaivel from China exclusive access to the UCL incredible social spaces at WelcomeAall Chapter locations across London. Perhaps you want to watch a film with friends at Chapter Highbury, have a sky-high drink in the 32nd floor bar at Chapter Spitalfields, or attend a fitness Member class at Chapter Kings Cross. Simply show your Chapter member card at reception or to security on the door and they’ll let you through. benefitsBeing a resident of Chapter means you enjoy exclusive And it’s not just the social spaces that access to all of our locations across London. you have access to, you can attend all the exciting events at the other CHAPTER SPITALFIELDS Chapters too. “It’s close to my university, the tube station and it’s very central. Everybody is very friendly and the CHAPTER IS YOUR HOME AND YOU HAVE events are a great way ACCESS TO EVERYTHING ON OFFER. to interact with everyone. All of the staff have been really helpful.” Victoria from France In this guide, you’ll find your event Istituto Marangoni plan for Semester 2. -

Local Plan Church End Growth Area Site Allocations BSSA1: Asiatic

Brent Publication Stage (Stage 3) Local Plan Church End Growth Area Site Allocations BSSA1: Asiatic Carpets Representations on behalf of Kelaty Properties LLP These Representations are submitted on behalf of Kelaty Properties LLP, freehold owners of a 2.3ha site (herein after referred to as the Asiatic Carpets site) that forms part of the BSSA1: Asiatic Carpets site allocation (which is the combination of the Asiatic Carpets and adjoining Cygnus Business Centre sites, herein after referred to as the allocated site). The Asiatic Carpets site is in single ownership and currently comprises a number of large industrial, office and warehouse buildings, as well as open storage, a car wash and builder’s yard. All existing tenants are short-term (albeit Asiatic Carpets as landowner have occupied the site for a number of years) and the buildings are reaching the end of their economic life. As outlined in our response to the preferred options Local Plan, it is the short to medium-term intention of the owners to rationalise their Asiatic Carpets business and either relocate, or operate from more efficient, modern space on site. The Council reviewed and provided commentary on our representations to the preferred options Local Plan within the ‘Summary of Comments to the preferred options Local Plan’ (see Document 1). The response considered our representation to raise three main issues, which can be summarised as follows: 1. Whether it should be necessary and appropriate for the redevelopment of the Asiatic Carpets site to provide replacement industrial floor space; 2. The phasing and deliverability of the Asiatic Carpets site in conjunction with the adjoining Cygnus Business Centre as a single allocation; and 3. -

Gladstone Park to Mapesbury

Route 2 - Gladstone Park, Mapesbury Dell and surrounds Route Highlights Just off route up Brook Road, you will see the Paddock War Brent Walks Stroll through Gladstone Park and enjoy the views over Room Bunker, codeword for the A series of healthy walks for all the family to enjoy the city of London and the walled gardens. This route alternative Cabinet War Room also includes historic sites including the remains of Dollis Bunker. An underground 1940’s Hill House, a WWII underground bunker and Old Oxgate bunker used during WWII by Farm. The route finishes by walking through Mapesbury Winston Churchill and the Conservation area to the award-winning Mapesbury Dell. Cabinet, it remains in its original Route 2 - Gladstone Park, state next to 107 Brook Road. You can take a full tour of 1 Start at Dollis Hill Tube Station and 2 take the Burnley the underground bunker twice a year. Purpose-built from Mapesbury Dell and surrounds Road exit. Go straight up 3 Hamilton Road. At the end reinforced concrete, this bomb-proof subterranean war of Hamilton Road turn left onto 4 Kendal Road and then citadel 40ft below ground has a map room, cabinet room right onto 5 Gladstone Park. Walk up to the north end and offices and is housed within a sub-basement protected of the park when you are nearing the edge 6 turn right. by a 5ft thick concrete roof. In the north east corner of the park you will see the Holocaust Memorial and the footprint of Dollis Hill House. Old Oxgate Farm is a Grade II Exit the park at 7 and walk up Dollis Hill Lane, and turn listed building thought to be left onto Coles Green Road 8. -

London's Rail & Tube Services

A B C D E F G H Towards Towards Towards Towards Towards Hemel Hempstead Luton Airport Parkway Welwyn Garden City Hertford North Towards Stansted Airport Aylesbury Hertford East London’s Watford Junction ZONE ZONE Ware ZONE 9 ZONE 9 St Margarets 9 ZONE 8 Elstree & Borehamwood Hadley Wood Crews Hill ZONE Rye House Rail & Tube Amersham Chesham ZONE Watford High Street ZONE 6 8 Broxbourne 8 Bushey 7 ZONE ZONE Gordon Hill ZONE ZONE Cheshunt Epping New Barnet Cockfosters services ZONE Carpenders Park 7 8 7 6 Enfield Chase Watford ZONE High Barnet Theydon Bois 7 Theobalds Chalfont Oakwood Grove & Latimer 5 Grange Park Waltham Cross Debden ZONE ZONE ZONE ZONE Croxley Hatch End Totteridge & Whetstone Enfield Turkey Towards Southgate Town Street Loughton 6 7 8 9 1 Chorleywood Oakleigh Park Enfield Lock 1 High Winchmore Hill Southbury Towards Wycombe Rickmansworth Moor Park Woodside Park Arnos Grove Chelmsford Brimsdown Buckhurst Hill ZONE and Southend Headstone Lane Edgware Palmers Green Bush Hill Park Chingford Northwood ZONE Mill Hill Broadway West Ruislip Stanmore West Finchley Bounds 5 Green Ponders End Northwood New Southgate Shenfield Hillingdon Hills 4 Edmonton Green Roding Valley Chigwell Harrow & Wealdstone Canons Park Bowes Park Highams Park Ruislip Mill Hill East Angel Road Uxbridge Ickenham Burnt Oak Key to lines and symbols Pinner Silver Street Brentwood Ruislip Queensbury Woodford Manor Wood Green Grange Hill Finchley Central Alexandra Palace Wood Street ZONE North Harrow Kenton Colindale White Hart Lane Northumberland Bakerloo Eastcote -

Irina Porter, Uncovering Kilburn's History: Part 7

Uncovering Kilburn’s History – Part 7 Thank you for joining me again for the final part of this Kilburn local history series. 1. New flats in Cambridge Road, opposite Granville Road Baths, c.1970. (Brent Archives online image 10127) In Part 6 we saw the major rebuilding that took place, particularly in South Kilburn, between the late 1940s and the 1970s. Many of the workers on the building sites were Irish. The new wave of Irish immigration to Northwest London, which reached its peak in the 1950s, was quickly transforming the area. As well as abundant work, Kilburn offered plenty of cheap accommodation, and a bustling High Road with cultural and eating establishments, many of them catering for the Irish population, who soon represented a majority in the area. ‘County Kilburn’ was dubbed Ireland’s 33rd county. 2. Kilburn's Irish culture – an Irish Festival poster and Kilburn Gaels hurling team. (From the internet) The Irish community, close-knit and mutually supportive, hit the headlines in the negative way in the 1970s, when Kilburn became a focal point for “the Troubles” in London. On 8 June 1974, an estimated 3,000 came out onto the streets of Kilburn for the funeral procession of Provisional IRA member Michael Gaughan. An Irishman, who had lived in Kilburn, Gaughan was imprisoned for an armed bank robbery in 1971 and in 1974 died as the result a hunger strike. Gaughan’s coffin, accompanied by an IRA guard of honour, was taken from the Crown at Cricklewood through Kilburn to the Catholic Church of the Sacred Heart in Quex Road, before being flown to Dublin for another ceremony and funeral. -

Residential Population

NHS_Big_Map_3_Brent.pdf 1 05/06/2015 16:19 NHS Dental Practices in Brent A Emergency Service 21 AG Dentistry 43 Harrow Road Dental Out Of Hours Dental 98 Chamberlayne Road, Surgery Help Line Kensal Rise, London 883 Harrow Road, 0203 4021312 NW10 3JN Middlesex HA0 2RH 020 8964 2072 020 8904 1409 Total B Complaints Team 22 Dental Practice 44 Dental Practice 0300 311 2233 371 Kenton Road, Kenton, 63 Park View Road, Middlesex HA3 0XS London NW10 1AJ 56 Dental 020 8907 5886 020 8452 9085 Practices 1 Dental Practice 23 Park Avenue Dental Care 45 Craven Park Dental Practice 223 High Road, Willesden, 44 Park Avenue Nth, 2 Craven Park, London NW10 2RY Willesden Green, London London NW10 8SY 020 8459 7131 NW10 1JY 020 8965 3605 020 8452 6889 2 Kenton Clinic 24 Dental Practice 46 Brentfield Medical Centre 8 Upton Gardens, Harrow, 258 Ealing Road, Wembley, 10 Kingfisher Way, Middlesex HA3 0DL Middlesex HA0 4QL Brentfield Road, Neasden, 55 020 8907 7939 020 8902 1166 London NW10 8TF 020 8451 7226 Ixia Dental Kilburn Corner Dental Dental Practice S 3 25 47 50 t 319 Kenton Road, Kenton, Practice 47 Okehampton Road, a g Harrow HA3 0XN 61 Kilburn High Road, London NW10 3EN L 020 8907 9575 London NW6 5SB 020 8459 2928 n 020 7624 6383 H o n e 4 Rose Garden Dental 26 Wembley High Street 48 Willesden Dental Centre y Practice Dental Practice 248 High Road, Willesden, p 280 Church Lane, Kinsgbury, 444b High Road, Wembley, London NW10 2NX o t 32 London NW9 8LU Middlesex HA9 6AH 020 8459 4344 22 3 L 020 8200 5588 020 8902 0877 Rd 17 n nton Ke 6 36 5 Surgery@102 -

Harlesden Neighbourhood Plan

Appendix A: Harlesden Neighbourhood Plan HARLESDEN NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2019 - 2034 May 2019 Images in this document produced by Harlesden Neighbourhood Hood Forum unless otherwise stated. With thanks to Crisis Brent Community Researcher volunteers and photography group, as well as to our Forum members, local volunteers and all those who have contributed to the preparation of this document. A welcome from the Chair of the Harlesden Neighbourhood Forum Welcome to the Harlesden Neighbourhood Plan - a vision of how Harlesden can develop and grow over the next fifteen years whilst preserving its distinct heritage. Policies within the Neighbourhood Plan are restricted to matters amenable to planning – primarily the built, physical environment. The Plan’s remit does not extend to local services, cultural and arts activities or economic development, although of course planning policies can contribute to the protection and growth of all these things. Harlesden Neighbourhood Forum’s ambitions for our area however go far beyond planning policy. We hope you will continue to engage with the development of the Plan and work of the Forum throughout the formal process and beyond. Beyond the Plan we are keen to develop an exciting and unique offer for visitors and residents alike based on Harlesden’s cultural and artistic diversity. Harlesden is a colourful, neighbourhood in north west London, home to people from across the world, where you can sample a dizzying range of cultures and cuisines from Brazilian to Polish, Trinidadian to Somali. Where, in a single visit, you can pop into some of the best Caribbean food stores in London, admire the beauty and history of Harlesden’s churches or enjoy the outdoors in beautiful Roundwood Park or one of our newly regenerated pocket parks. -

224 Wembley – Park Royal – St Raphael's

224 Wembley–ParkRoyal–StRaphael's 224 Mondays to Fridays WembleyStadiumStation 0505 0525 0545 0605 0623 0642 0700 0717 0734 0752 0813 0834 0855 0916 0936 0956 1016 1036 WembleyCentralStation 0508 0528 0548 0608 0626 0646 0704 0721 0738 0757 0818 0839 0900 0921 0941 1001 1021 1041 AlpertonSainsbury's 0516 0536 0556 0617 0635 0655 0713 0730 0748 0808 0829 0850 0910 0931 0951 1011 1031 1051 StonebridgeParkAceCafe 0523 0543 0604 0625 0644 0704 0722 0740 0800 0820 0841 0901 0921 0942 1002 1022 1042 1102 ParkRoyalIveaghAvenue 0528 0548 0609 0631 0650 0710 0729 0748 0808 0828 0848 0908 0928 0948 1008 1028 1048 1108 ParkRoyalCentralMiddlesexHospital 0536 0556 0618 0640 0700 0720 0740 0800 0820 0840 0900 0921 0941 1001 1021 1041 1101 1121 BrentfieldRd.SwaminarayanTemple 0545 0605 0627 0649 0710 0730 0751 0812 0832 0852 0911 0931 0951 1011 1031 1051 1111 1131 BrentParkTesco 0551 0611 0634 0657 0719 0739 0801 0822 0842 0902 0920 0940 1000 1020 1040 1100 1120 1140 StRaphael'sEstatePitfieldWay 0555 0615 0638 0701 0723 0744 0806 0827 0847 0907 0925 0945 1005 1025 1045 1105 1125 1145 WembleyStadiumStation 1056 1116 1136 1156 1216 1236 1256 1316 1336 1356 1417 1437 1457 1518 1539 1600 1622 1644 WembleyCentralStation 1101 1121 1141 1201 1222 1242 1302 1322 1342 1402 1423 1443 1503 1524 1545 1607 1629 1651 AlpertonSainsbury's 1111 1131 1151 1212 1233 1253 1313 1333 1353 1413 1434 1454 1515 1536 1557 1619 1641 1703 StonebridgeParkAceCafe 1122 1142 1202 1223 1244 1304 1324 1344 1404 1424 1446 1507 1528 1549 1610 1632 1654 1716 ParkRoyalIveaghAvenue 1128