Chr Start End Size Gene Exon 1 69482 69600 118 OR4F5 1 1 877520

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Note Hominoid Fission of Chromosome 14/15 and Role Of

Supplemental Note Supplemental Note Hominoid fission of chromosome 14/15 and role of segmental duplications Giuliana Giannuzzi, Michele Pazienza, John Huddleston, Francesca Antonacci, Maika Malig, Laura Vives, Evan E. Eichler and Mario Ventura 1. Analysis of the macaque contig spanning the hominoid 14/15 fission site We grouped contig clones based on their FISH pattern on human and macaque chromosomes (Groups F1, F2, F3, G1, G2, G3, and G4). Group F2 clones (Hsa15b- and Hsa15c-positive) showed a single signal on macaque 7q and three signal clusters on human chromosome 15: at the orthologous 15q26, as expected, as well as at 15q11–14 and 15q24–25, which correspond to the actual and ancestral pericentromeric regions, respectively (Ventura et al. 2003). Indeed, this locus contains an LCR15 copy (Pujana et al. 2001) in both the macaque and human genomes. Most BAC clones were one-end anchored in the human genome (chr15:100,028–100,071 kb). In macaque this region experienced a 64 kb duplicative insertion from chromosome 17 (orthologous to human chromosome 13) (Figure 2), with the human configuration (absence of insertion) likely being the ancestral state because it is identical in orangutan and marmoset. Four Hsa15b- positive clones mapped on macaque and human chromosome 19, but neither human nor macaque assemblies report the STS Hsa15b duplicated at this locus. The presence of assembly gaps in macaque may explain why the STS is not annotated in this region. We aligned the sequence of macaque CH250-70H12 (AC187495.2) versus its human orthologous sequence (hg18 chr15:100,039k-100,170k) and found a 12 kb human expansion through tandem duplication of a ~100 bp unit corresponding to a portion of exon 20 of DNM1 (Figure S3). -

Genetic Variation Across the Human Olfactory Receptor Repertoire Alters Odor Perception

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/212431; this version posted November 1, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Genetic variation across the human olfactory receptor repertoire alters odor perception Casey Trimmer1,*, Andreas Keller2, Nicolle R. Murphy1, Lindsey L. Snyder1, Jason R. Willer3, Maira Nagai4,5, Nicholas Katsanis3, Leslie B. Vosshall2,6,7, Hiroaki Matsunami4,8, and Joel D. Mainland1,9 1Monell Chemical Senses Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA 2Laboratory of Neurogenetics and Behavior, The Rockefeller University, New York, New York, USA 3Center for Human Disease Modeling, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA 4Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA 5Department of Biochemistry, University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil 6Howard Hughes Medical Institute, New York, New York, USA 7Kavli Neural Systems Institute, New York, New York, USA 8Department of Neurobiology and Duke Institute for Brain Sciences, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA 9Department of Neuroscience, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA *[email protected] ABSTRACT The human olfactory receptor repertoire is characterized by an abundance of genetic variation that affects receptor response, but the perceptual effects of this variation are unclear. To address this issue, we sequenced the OR repertoire in 332 individuals and examined the relationship between genetic variation and 276 olfactory phenotypes, including the perceived intensity and pleasantness of 68 odorants at two concentrations, detection thresholds of three odorants, and general olfactory acuity. -

Assembly and Annotation of an Ashkenazi Human Reference Genome

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.18.997395; this version posted March 18, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Assembly and Annotation of an Ashkenazi Human Reference Genome Alaina Shumate1,2,† Aleksey V. Zimin1,2,† Rachel M. Sherman1,3 Daniela Puiu1,3 Justin M. Wagner4 Nathan D. Olson4 Mihaela Pertea1,2 Marc L. Salit5 Justin M. Zook4 Steven L. Salzberg1,2,3,6* 1Center for Computational Biology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 2Department of Biomedical Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 3Department of Computer Science, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 4National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD 5Joint Initiative for Metrology in Biology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 6Department of Biostatistics, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD †These authors contributed equally to this work. *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract Here we describe the assembly and annotation of the genome of an Ashkenazi individual and the creation of a new, population-specific human reference genome. This genome is more contiguous and more complete than GRCh38, the latest version of the human reference genome, and is annotated with highly similar gene content. The Ashkenazi reference genome, Ash1, contains 2,973,118,650 nucleotides as compared to 2,937,639,212 in GRCh38. Annotation identified 20,157 protein-coding genes, of which 19,563 are >99% identical to their counterparts on GRCh38. Most of the remaining genes have small differences. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Clinical Vignette Novel Bi-Allelic Variants in GJC2 Associated

Clinical Vignette Novel Bi-allelic Variants in GJC2 Associated Pelizaeus- Merzbacher-like Disease 1: Clinical Clues and Differential Diagnosis Veronica Arora, Sapna Sandal, Ishwar Verma Institute of Medical Genetics and Genomics, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi Correspondence to: Dr Ishwar C Verma Email: [email protected] Abstract the environment and did not follow objects. Head titubation was present. There was no facial dys- Hypomyelinating Leukodystrophy-2 (HLD2) or morphism. Anthropometric measurements were Pelizaeus-Merzbacher-like disease 1 (PMLD1) is a as follows: length 82cm (+1.2SD), weight 10.6Kg slowly progressive leukodystrophy characterized (+1.1SD) and head circumference 47.7cm (+1.2SD). by nystagmus, hypotonia, and developmental Central nervous system examination showed bilat- delay. It is a close differential diagnosis for eral pendular nystagmus, axial hypotonia, dystonic Pelizaeus- Merzbacher disease (PMD) and should posturing, and choreo-athetoid movements (Figure be suspected in patients with features of PMD but 1). Deep tendon reflexes were brisk with extensor who are negative on testing for duplication of the plantar responses. The rest of the systemic PLP1 gene. We describe a case of a 16-month-old examination was non-contributory. MRI of the boy with a novel homozygous mutation in the GJC2 brain (axial view) showed diffuse hypo-myelination gene resulting in hypomyelinating leukodystrophy- in the peri-ventricular and sub-cortical area and 2. The clinical clues as well as features of other cerebellar white matter changes (Figure 2). disorders presenting similarly are discussed. Given the presence of hypotonia, brisk reflexes, nystagmus and hypomyelination on MRI, a deletion Clinical description duplication analysis for the PLP1 gene was done which was negative. -

Transcriptomic Analysis of Native Versus Cultured Human and Mouse Dorsal Root Ganglia Focused on Pharmacological Targets Short

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/766865; this version posted September 12, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. Transcriptomic analysis of native versus cultured human and mouse dorsal root ganglia focused on pharmacological targets Short title: Comparative transcriptomics of acutely dissected versus cultured DRGs Andi Wangzhou1, Lisa A. McIlvried2, Candler Paige1, Paulino Barragan-Iglesias1, Carolyn A. Guzman1, Gregory Dussor1, Pradipta R. Ray1,#, Robert W. Gereau IV2, # and Theodore J. Price1, # 1The University of Texas at Dallas, School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences and Center for Advanced Pain Studies, 800 W Campbell Rd. Richardson, TX, 75080, USA 2Washington University Pain Center and Department of Anesthesiology, Washington University School of Medicine # corresponding authors [email protected], [email protected] and [email protected] Funding: NIH grants T32DA007261 (LM); NS065926 and NS102161 (TJP); NS106953 and NS042595 (RWG). The authors declare no conflicts of interest Author Contributions Conceived of the Project: PRR, RWG IV and TJP Performed Experiments: AW, LAM, CP, PB-I Supervised Experiments: GD, RWG IV, TJP Analyzed Data: AW, LAM, CP, CAG, PRR Supervised Bioinformatics Analysis: PRR Drew Figures: AW, PRR Wrote and Edited Manuscript: AW, LAM, CP, GD, PRR, RWG IV, TJP All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/766865; this version posted September 12, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Caracterización De Las Bases Genéticas De Ataxias Hereditarias

8. Appendices Appendix I: Genetic tests previously performed for patients included in WES analysis and SCA36 screening. These analyses include the most common forms of ADCA and ARCA caused by trinucleotide expansions and a panel containing genes relevant for different types of ataxia. SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6, SCA7, SCA12, SCA17 and DRPLA (Dentatorubral- pallidoluysian atrophy): caused by CAG triplet expansions. SCA8: caused by CTG triplet expansions. Friedreich’s ataxia: caused by GAA triplet expansions. SureSelect Human All Exon V6Panel (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA): this panel was used to study both the coding and the intronic flanking regions of ataxia related genes through NGS. Different sets of genes were used for different types of ataxia. - Episodic ataxia: ATP1A2, ATP1A3, CACNA1A, CACNA1S, CACNB4, KCNA1, SCN1A, SCN2A, SCN4A, SLC1A3. - Dominant ataxia: AFG3L2, ATP1A3, CACNA1A, CACNA1G, CACNB4, CCDC88C, DNMT1, EEF2, ELOVL4, ELOVL5, FAT2, FGF12, FGF14, ITPR1,KCNA1, KCNC3, KCND3, PDYN, PRKCG, SCN2A, SLC1A3, SPG7, SPTBN2, TBP, TGM6, TMEM240, TTBK2, TUBB4A, TRPC2, ME, PLD3. - Recessive ataxia: ABHD12, ADCK3, ANO10, APTX, ATCAY, ATM, ATP8A2, C10orf2, CA8, CWF19L1, ADCK3, CYP27A1, DNAJC19, FXN, GRM1,KCNJ10, KIAA0226, MRE11, MTPAP, PIK3R5, PLEKHG4, PMPCA, PNKP, POLG, RNF216, SACS, SETX, SIL1, SNX14, SYNE1, SYT14, TDP1, TPP1, TTPA, VLDLR, WDR81, WWOX - Complex disorders with prominent ataxia (AR): AFG3L2, CLCN2, COX20, CP, DARS2, FLVCR1, HEXA, HEXB, ITPR1, LAMA1, MTTP, NCP1, NCP2, PLA2G6, PM2, PNPLA6, SPTBN2. - Complex disorders with occasional ataxia (AR): ACO2, AHI1, ARL13B, CC2D2A, CLN5, CLN6, EIF2B1, EIF2B2, EIF2B3, EIF2B4, EIF2B5, GOSR2, L2HGDH, OPA1, PEX7, PHYH, POLR3A, POLR3B, PTF1A, SLC17A5, SLC25A46, SLC52A2, SLC6A19, TSFM, TXN2, WFS1. - Disorders reported with ataxia but not included in the differential diagnosis: EPM2A, NHLRC1, MLC1, COL18A1, HSD17B4, PEX2, WFS1, ASPA, ARSA, SLC2A1. -

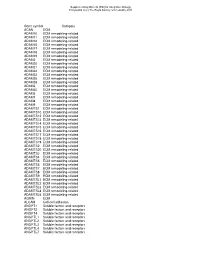

Gene Symbol Category ACAN ECM ADAM10 ECM Remodeling-Related ADAM11 ECM Remodeling-Related ADAM12 ECM Remodeling-Related ADAM15 E

Supplementary Material (ESI) for Integrative Biology This journal is (c) The Royal Society of Chemistry 2010 Gene symbol Category ACAN ECM ADAM10 ECM remodeling-related ADAM11 ECM remodeling-related ADAM12 ECM remodeling-related ADAM15 ECM remodeling-related ADAM17 ECM remodeling-related ADAM18 ECM remodeling-related ADAM19 ECM remodeling-related ADAM2 ECM remodeling-related ADAM20 ECM remodeling-related ADAM21 ECM remodeling-related ADAM22 ECM remodeling-related ADAM23 ECM remodeling-related ADAM28 ECM remodeling-related ADAM29 ECM remodeling-related ADAM3 ECM remodeling-related ADAM30 ECM remodeling-related ADAM5 ECM remodeling-related ADAM7 ECM remodeling-related ADAM8 ECM remodeling-related ADAM9 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS1 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS10 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS12 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS13 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS14 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS15 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS16 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS17 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS18 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS19 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS2 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS20 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS3 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS4 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS5 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS6 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS7 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS8 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTS9 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTSL1 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTSL2 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTSL3 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTSL4 ECM remodeling-related ADAMTSL5 ECM remodeling-related AGRIN ECM ALCAM Cell-cell adhesion ANGPT1 Soluble factors and receptors -

Effect of Nanoparticles on the Expression and Activity of Matrix Metalloproteinases

Nanotechnol Rev 2018; 7(6): 541–553 Review Magdalena Matysiak-Kucharek*, Magdalena Czajka, Krzysztof Sawicki, Marcin Kruszewski and Lucyna Kapka-Skrzypczak Effect of nanoparticles on the expression and activity of matrix metalloproteinases https://doi.org/10.1515/ntrev-2018-0110 Received September 14, 2018; accepted October 11, 2018; previously 1 Introduction published online November 15, 2018 Matrix metallopeptidases, commonly known as matrix Abstract: Matrix metallopeptidases, commonly known metalloproteinases (MMPs), are zinc-dependent proteo- as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), are a group of pro- lytic enzymes whose primary function is the degradation teolytic enzymes whose main function is the remodeling and remodeling of extracellular matrix (ECM) compo- of the extracellular matrix. Changes in the activity of nents. ECM is a complex, dynamic structure that condi- these enzymes are observed in many pathological states, tions the proper tissue architecture. MMPs by digesting including cancer metastases. An increasing body of evi- ECM proteins eliminate structural barriers and allow dence indicates that nanoparticles (NPs) can lead to the cell migration. Moreover, by hydrolyzing extracellularly deregulation of MMP expression and/or activity both in released proteins, MMPs can change the activity of many vitro and in vivo. In this work, we summarized the current signal peptides, such as growth factors, cytokines, and state of knowledge on the impact of NPs on MMPs. The chemokines. MMPs are involved in many physiological literature analysis showed that the impact of NPs on MMP processes, such as embryogenesis, reproduction cycle, or expression and/or activity is inconclusive. NPs exhibit wound healing; however, their increased activity is also both stimulating and inhibitory effects, which might be associated with a number of pathological conditions, such dependent on multiple factors, such as NP size and coat- as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and neurodegenera- ing or a cellular model used in the research. -

Effect of Genetic Variation on Salt, Sweet, Fat and Bitter Taste

Effect of Genetic Variation on Salt, Sweet, Fat and Bitter Taste by Andre Dias A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Nutritional Sciences University of Toronto © Copyright by Andre Dias 2014 Effect of Genetic Variation on Salt, Sweet, Fat and Bitter Taste Andre Dias Doctor of Philosophy Department of Nutritional Sciences University of Toronto 2014 Abstract Background: Taste is one of the primary determinants of food intake and taste function can be influenced by a number of factors including genetics. However, little is known about the relationship between genetic variation, taste function, food preference and intake. Objective: To examine the effect of variation in genes involved in the perception of salt, sweet, fat and bitter compounds on taste function, food preference and consumption. Methods: Subjects were drawn from the Toronto Nutrigenomics and Health Study, a population of healthy men (n=487) and women (n = 1058). Dietary intake was assessed using a 196-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) and food preference was assessed using a 63-item food preference checklist. Subsets of individuals were phenotyped to assess taste function in response to salt (n=95), sucrose (n=95), oleic acid (n=21) and naringin (n=685) stimuli. Subjects were genotyped for Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) in candidate genes. Results: Of the SNPs examined in putative salt taste receptor genes (SCNN1(A, B, D, G), TRPV1), the rs9939129 and rs239345 SNPs in the SCNN1B gene and rs8065080 in the TRPV1 gene were associated with salt taste. In the TAS1R2 gene, the rs12033832 was associated with sucrose taste and sugar intake. -

A Translaminar Genetic Logic for the Circuit Identity of Intracortically-Projecting Neurons

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/290395; this version posted March 28, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Title A translaminar genetic logic for the circuit identity of intracortically-projecting neurons Authors Esther Klingler1, Andres De la Rossa1,3, Sabine Fièvre1, Denis Jabaudon1,2 1Department of Basic Neurosciences, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland. 2Clinic of Neurology, Geneva University Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland. 3Present address: Department of Cell Biology, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland. Correspondence should be addressed to D.J. ([email protected]). Abstract Distinct subtypes of intracortically-projecting neurons (ICPN) are present in all layers, allowing propagation of information within and across cortical columns. How the molecular identities of ICPN relate to their defining anatomical and functional properties is unknown. Here we show that the transcriptional identities of ICPN primarily reflect their input-output connectivities rather than their birth dates or laminar positions. Thus, conserved circuit-related transcriptional programs are at play across cortical layers, which may preserve canonical circuit features across development and evolution. bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/290395; this version posted March 28, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Introduction Neurons of the neocortex are organized into six radial layers, which have appeared at different times during evolution, with the superficial layers representing a more recent acquisition. Input to the neocortex predominantly reaches superficial layers (SL, i.e. -

Insurance and Advance Pay Test Requisition

Insurance and Advance Pay Test Requisition (2021) For Specimen Collection Service, Please Fax this Test Requisition to 1.610.271.6085 Client Services is available Monday through Friday from 8:30 AM to 9:00 PM EST at 1.800.394.4493, option 2 Patient Information Patient Name Patient ID# (if available) Date of Birth Sex designated at birth: 9 Male 9 Female Street address City, State, Zip Mobile phone #1 Other Phone #2 Patient email Language spoken if other than English Test and Specimen Information Consult test list for test code and name Test Code: Test Name: Test Code: Test Name: 9 Check if more than 2 tests are ordered. Additional tests should be checked off within the test list ICD-10 Codes (required for billing insurance): Clinical diagnosis: Age at Initial Presentation: Ancestral Background (check all that apply): 9 African 9 Asian: East 9 Asian: Southeast 9 Central/South American 9 Hispanic 9 Native American 9 Ashkenazi Jewish 9 Asian: Indian 9 Caribbean 9 European 9 Middle Eastern 9 Pacific Islander Other: Indications for genetic testing (please check one): 9 Diagnostic (symptomatic) 9 Predictive (asymptomatic) 9 Prenatal* 9 Carrier 9 Family testing/single site Relationship to Proband: If performed at Athena, provide relative’s accession # . If performed at another lab, a copy of the relative’s report is required. Please attach detailed medical records and family history information Specimen Type: Date sample obtained: __________ /__________ /__________ 9 Whole Blood 9 Serum 9 CSF 9 Muscle 9 CVS: Cultured 9 Amniotic Fluid: Cultured 9 Saliva (Not available for all tests) 9 DNA** - tissue source: Concentration ug/ml Was DNA extracted at a CLIA-certified laboratory or a laboratory meeting equivalent requirements (as determined by CAP and/or CMS)? 9 Yes 9 No 9 Other*: If not collected same day as shipped, how was sample stored? 9 Room temp 9 Refrigerated 9 Frozen (-20) 9 Frozen (-80) History of blood transfusion? 9 Yes 9 No Most recent transfusion: __________ /__________ /__________ *Please contact us at 1.800.394.4493, option 2 prior to sending specimens.