In the Place Just Right (Keynote Address)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

37466 CFMTA Spring Edition 04

THE CANADIAN MUSIC TEACHER LE PROFESSEUR DE MUSIQUE CANADIEN CFMTA FCAPM SPRING EDITION 2004 • WHAT’S INSIDE . Greetings from CFMTA ...................... 4 National Convention .......................... 6 Contemplating the Art of Teaching .. 12 ACNMP ........................................... 18 Carleton W. Elliott ............................ 19 Marek Jablonski Endowment ............ 21 Music Teachers’ North America Conference ....................................... 22 From the Provinces ........................... 24 Multimusic Canada for the New Millennium ....................................... 31 Where Once They Stood .................. 32 The Science and Art of Musical Memorization ................................... 36 30 Fingers, 6 Feet Under .................. 43 Networking With Piano Teachers Across Canada .................................. 44 Book Reviews ................................... 45 Executive Directory .......................... 53 THE CANADIAN MUSIC TEACHER LE PROFESSEUR DE MUSIQUE CANADIEN Official Journal of The Canadian Federation of Music Teachers’ Associations Vol. 54, No. 3 Circulation 3400 Founded 1935 The Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music (Publishing) Limited New Piano Syllabus 200 3–2004 from The Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music Selected Piano Examination Pieces 200 3–2004 • new syllabus • one album per grade, Grades 1 to 8 • each album contains nine pieces from the syllabus for Grades 1 to 7, and twelve pieces for Grade 8 Teaching Notes on Piano Examination Pieces 200 3–2004 -

74Th Baldwin-Wallace College Bach Festival

The 74th Annual BALDWIN-WALLACE Bach Festival Annotated Program April 21-22, 2006 Save the date! 2007 75th B-W BACH FESTIVAL Friday, Saturday, and Sunday April 20–22, 2007 Including a combined concert with the Bethlehem Bach Choir, celebrating its 100th Festival, in Severance Hall. The Mass in B Minor will be featured. Check our Web site for details www.bw.edu/bachfest Featured Soloists presented with support from the E. Nakamichi Foundation and The Adrianne and Robert Andrews Bach Festival Fund in honor of Amelia & Elias Fadil BALDWIN-WALLACE COLLEGE SEVENTY-FOURTH ANNUAL BACH FESTIVAL THE OLDEST COLLEGIATE BACH FESTIVAL IN THE NATION ANNOTATED PROGRAM APRIL 21–22, 2006 DEDICATION THE SEVENTY-FOURTH ANNUAL BACH FESTIVAL IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED TO RUTH PICKERING (1918–2005), WHO SO LOVED MUSIC, THE BALDWIN-WALLACE COLLEGE BACH FESTIVAL AND CONSERVATORY CONCERTS, THAT SHE AND HER LATE HUSBAND, DON, HAD THEIR NAMES ENGRAVED ON BRASS PLAQUES AND AFFIXED TO THEIR FAVORITE SEATS, DD 24 AND DD 25, IN THE BALCONY OF GAMBLE HALL, KULAS MUSICAL ARTS BUILDING. SHE WILL BE REMEMBERED WITH MUCH LOVE BY MANY FROM THIS COMMUNITY, IN WHICH SHE WAS SO ACTIVE. Third Sunday Chapel Series at Baldwin-Wallace College Lindsay-Crossman A concert series under the direction of Warren Scharf, Margaret Scharf, and Nicole Keller 2006-2007 Concert Schedule Third Sundays at 7:45 p.m. Our Sixth Season October 15, 2006 March 18, 2007 November 19, 2006 April 15, 2007 December 17, 2006 The public is warmly invited to attend these free concerts. The Chapel is handicapped accessible. -

Max Neuhaus, R. Murray Schafer, and the Challenges of Noise

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2018 MAX NEUHAUS, R. MURRAY SCHAFER, AND THE CHALLENGES OF NOISE Megan Elizabeth Murph University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2018.233 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Murph, Megan Elizabeth, "MAX NEUHAUS, R. MURRAY SCHAFER, AND THE CHALLENGES OF NOISE" (2018). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 118. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/118 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Presenter Bios

PRESENTER BIOGRAPHIES Anthony, Wayne Wayne Anthony is a thirty-year veteran of the arts scene in the Toledo area. He has been on the faculties of Maumee Valley Country Day School, Lourdes University, Cedarville University, and Owens Community College. He was the conductor of the Perrysburg Symphony Chorale, the Ballet Theatre of Toledo Orchestra, and the presently heads the SonoNovo Chamber Orchestra. He has been awarded a number of grants for his compositions including the Prix de Nadie Boulanger from the École Americane des Artes in Fontainbleau, France, and most recently was named a semi-finalist in the American Prize for Compostion, Theatre/Opera/Ballet division. His is a pianist and organist and is a member of the Anthony/Brown Piano duo and the American Guild of Organists. He has just returned from two-year hiatus in Boston where he served as organist at Church of Our Saviour Episcopal in Middleboro and was on the faculty of the Bay Colony Performing Arts Academy in Foxboro. AtWood, Thomas Mr. Thomas Atwood is an Associate Professor of Information Literacy for The College of University Libraries at The University of Toledo. His work has appeared in the Journal of Religious & Theological Information, Children’s Literature, College & Undergraduate Libraries, Names: A Journal of Onomastics, and The Journal of Academic Librarianship. He currently serves as the subject bibliographer to the Department of Music. Batzner, Jay Jay C. Batzner (b. 1974) is a composer and zazen practitioner. Jay’s music has been performed at new music festivals such as Society for Composers, Inc., College Music Society, Society for Electro- Acoustic Music in the US, and Electronic Music Midwest as well as instrument performance societies including the National Flute Association, International Horn Society, and North American Saxophone Alliance. -

75Thary 1935 - 2010

ANNIVERS75thARY 1935 - 2010 The Music & the Artists of the Bach Festival Society The Mission of the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park, Inc. is to enrich the Central Florida community through presentation of exceptionally high-quality performances of the finest classical music in the repertoire, with special emphasis on oratorio and large choral works, world-class visiting artists, and the sacred and secular music of Johann Sebastian Bach and his contemporaries in the High Baroque and Early Classical periods. This Mission shall be achieved through presentation of: • the Annual Bach Festival, • the Visiting Artists Series, and • the Choral Masterworks Series. In addition, the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park, Inc. shall present a variety of educational and community outreach programs to encourage youth participation in music at all levels, to provide access to constituencies with special needs, and to participate with the community in celebrations or memorials at times of significant special occasions. Adopted by a Resolution of the Bach Festival Society Board of Trustees The Bach Festival Society of Winter Park, Inc. is a private non-profit foundation as defined under Section 509(a)(2) of the Internal Revenue Code and is exempt from federal income taxes under IRC Section 501(c)(3). Gifts and contributions are deductible for federal income tax purposes as provided by law. A copy of the Bach Festival Society official registration (CH 1655) and financial information may be obtained from the Florida Division of Consumer Services by calling toll-free 1-800-435-7352 within the State. Registration does not imply endorsement, approval, or recommendation by the State. -

VB3 / A/ O,(S0-02

/VB3 / A/ O,(s0-02 A SURVEY OF THE RESEARCH LITERATURE ON THE FEMALE HIGH VOICE THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Roberta M. Stephen, B. Mus., A. Mus., A.R.C.T. Denton, Texas December, 1988 Stephen, Roberta M., Survey of the Research Literature on the Female High Voice. Master of Arts (Music), December, 1988, 161 pp., 11 tables, 13 illustrations, 1 appendix, bibliography, partially annotated, 136 titles. The location of the available research literature and its relationship to the pedagogy of the female high voice is the subject of this thesis. The nature and pedagogy of the female high voice are described in the first four chapters. The next two chapters discuss maintenance of the voice in conventional and experimental repertoire. Chapter seven is a summary of all the pedagogy. The last chapter is a comparison of the nature and the pedagogy of the female high voice with recommended areas for further research. For instance, more information is needed to understand the acoustic factors of vibrato, singer's formant, and high energy levels in the female high voice. PREFACE The purpose of this thesis is to collect research about the female high voice and to assemble the pedagogy. The science and the pedagogy will be compared to show how the two subjects conform, where there is controversy, and where more research is needed. Information about the female high voice is scattered in various periodicals and books; it is not easily found. -

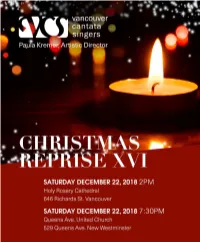

Reprise2018-Webedition.Pdf

The Vancouver Cantata Singers The VCS Board Paula Kremer, Artistic Director President: Sarah McNair Rachel Brown Eric Biskupski Vice-President: Jesse Read Treasurer: Christina Cho Emily Cheung Mark Anthony Briand Secretary: Jim Sanyshyn Missy Clarkson Sam Dabrusin Hannah Gee Dean Edmundson Directors: Melody Yiu, Beth Helsley Sarah McGrath Andrew Lennox Trevor Mangion, Missy Clarkson Wendy McMillan Daniel Marshall Singers’ Rep: Sarah McGrath Benila Ninan Taka Shimojima Asha Pratt-Johnson Nick Sommer The VCS Staff Eve Richardson Troy Topnik General Manager: Michelle Herrewynen Front of House Manager: Genevieve MacKay Melanie Adams Peter Alexander Maureen Bennington Andy Booth Ann Chen Derrick Christian Elspeth Finlay Doug Colpitts Beth Helsley Chris Doughty www.vancouvercantatasingers.com Nina Horvath Matthew Fisher Follow us on Katie Horst Gerald Harder Erik Kallo J. Evan Kreider Sarah McNair Larry Nickel Dave Rosborough Born in Vancouver and educated at the Vancouver Academy of Music and the University of British Columbia, Paula Kremer has studied choral conducting in courses and workshops at Eton, Westminster Choir College, the Eastman School of Music and the University of Michigan. Holding an ARCT in both piano and voice from the Royal Conservatory of Music, Paula has also studied voice with Phyllis Mailing, Bruce Pullan, Marisa Gaetanne and Laura Pudwell, and piano from Margot Ehling. A full-time faculty member of the School of Music at Vancouver Community College, teaching voice, solfege, and choir, she was also the director of two Vancouver Bach Choir ensembles for young adults from 2009-17, the Vancouver Bach Youth Choir and Sarabande Chamber Choir. Paula joined the alto section of our choir in 1994, and has been the Vancouver Cantata Singers’ Artistic Director since 2013. -

Georg Friedrich Händel (1685-1759)

Georg Friedrich Händel (1685-1759) Sämtliche Werke / Complete works in MP3-Format Details Georg Friedrich Händel (George Frederic Handel) (1685-1759) - Complete works / Sämtliche Werke - Total time / Gesamtspielzeit 249:50:54 ( 10 d 10 h ) Titel/Title Zeit/Time 1. Opera HWV 1 - 45, A11, A13, A14 116:30:55 HWV 01 Almira 3:44:50 1994: Fiori musicali - Andrew Lawrence-King, Organ/Harpsichord/Harp - Beate Röllecke Ann Monoyios (Soprano) - Almira, Patricia Rozario (Soprano) - Edilia, Linda Gerrard (Soprano) - Bellante, David Thomas (Bass) - Consalvo, Jamie MacDougall (Tenor) - Fernando, Olaf Haye (Bass) - Raymondo, Christian Elsner (Tenor) - Tabarco HWV 06 Agrippina 3:24:33 2010: Akademie f. Alte Musik Berlin - René Jacobs Alexandrina Pendatchanska (Soprano) - Agrippina, Jennifer Rivera (Mezzo-Soprano) - Nerone, Sunhae Im (Soprano) - Poppea, Bejun Mehta (Counter-Tenor) - Ottone, Marcos Fink (Bass-Bariton) - Claudio, Neal Davis (Bass-Bariton) - Pallante, Dominique Visse (Counter-Tenor) - Narciso, Daniel Schmutzhard (Bass) - Lesbo HWV 07 Rinaldo 2:54:46 1999: The Academy of Ancient Music - Christopher Hogwood Bernarda Fink (Mezzo-Sopran) - Goffredo, Cecilia Bartoli (Mezzo-Sopran) - Almirena, David Daniels (Counter-Tenor) - Rinaldo, Daniel Taylor (Counter-Tenor) - Eustazio, Gerald Finley (Bariton) - Argante, Luba Orgonasova (Soprano) - Armida, Bejun Mehta (Counter-Tenor) - Mago cristiano, Ana-Maria Rincón (Soprano) - Donna, Sirena II, Catherine Bott (Soprano) - Sirena I, Mark Padmore (Tenor) - Un Araldo HWV 08c Il Pastor fido 2:27:42 1994: Capella -

1976-77-Annual-Report.Pdf

TheCanada Council Members Michelle Tisseyre Elizabeth Yeigh Gertrude Laing John James MacDonaId Audrey Thomas Mavor Moore (Chairman) (resigned March 21, (until September 1976) (Member of the Michel Bélanger 1977) Gilles Tremblay Council) (Vice-Chairman) Eric McLean Anna Wyman Robert Rivard Nini Baird Mavor Moore (until September 1976) (Member of the David Owen Carrigan Roland Parenteau Rudy Wiebe Council) (from May 26,1977) Paul B. Park John Wood Dorothy Corrigan John C. Parkin Advisory Academic Pane1 Guita Falardeau Christopher Pratt Milan V. Dimic Claude Lévesque John W. Grace Robert Rivard (Chairman) Robert Law McDougall Marjorie Johnston Thomas Symons Richard Salisbury Romain Paquette Douglas T. Kenny Norman Ward (Vice-Chairman) James Russell Eva Kushner Ronald J. Burke Laurent Santerre Investment Committee Jean Burnet Edward F. Sheffield Frank E. Case Allan Hockin William H. R. Charles Mary J. Wright (Chairman) Gertrude Laing J. C. Courtney Douglas T. Kenny Michel Bélanger Raymond Primeau Louise Dechêne (Member of the Gérard Dion Council) Advisory Arts Pane1 Harry C. Eastman Eva Kushner Robert Creech John Hirsch John E. Flint (Member of the (Chairman) (until September 1976) Jack Graham Council) Albert Millaire Gary Karr Renée Legris (Vice-Chairman) Jean-Pierre Lefebvre Executive Committee for the Bruno Bobak Jacqueline Lemieux- Canadian Commission for Unesco (until September 1976) Lope2 John Boyle Phyllis Mailing L. H. Cragg Napoléon LeBlanc Jacques Brault Ray Michal (Chairman) Paul B. Park Roch Carrier John Neville Vianney Décarie Lucien Perras Joe Fafard Michael Ondaatje (Vice-Chairman) John Roberts Bruce Ferguson P. K. Page Jacques Asselin Céline Saint-Pierre Suzanne Garceau Richard Rutherford Paul Bélanger Charles Lussier (until August 1976) Michael Snow Bert E. -

Thursdays at Noon: Judy Loman, Harp and Nora Shulman, Flute

Thursdays at Noon: Judy Loman, harp and Nora Shulman, flute Thursday, January 31, 2019 at 12:10 pm Walter Hall, 80 Queen’s Park PROGRAM Chanson de Matin, Op. 15 No. 2 Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Sonata for Flute and Harp Adrian Grigor’yevich Shaposhnikov (1887-1967) i. Andante con moto-Allegro non troppo ii. Menuetto iii. Allegro molto Sonata for flute and harp, Op. 56 Lowell Liebermann (b. 1961) Histoire du Tango Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992) i. Bordel 1900 ii. Cafe 1930 iii. Night Club 1960 Follow @UofTMusic The Faculty of Music is a partner of the Bloor St. Culture Corridor Visit www.music.utoronto.ca bloorstculturecorridor.com We wish to acknowledge this land on which the University of Toronto operates. For thousands of years it has been the traditional land of the Huron-Wendat, the Seneca, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit River. Today, this meeting place is still the home to many Indigenous people from across Turtle Island and we are grateful to have the opportunity to work on this land. BIOGRAPHIES Recognized as one of the world’s of Toronto, and instructor of harp at the Royal Conservatory of foremost harp virtuosos, Judy Music in Toronto. She gives master-classes worldwide and has Loman graduated from the adjudicated at the International Harp Contest in Israel, the USA Curtis Institute of Music, where International Harp Contest and The Vera Dulova International she studied with the celebrated Harp Competition in Moscow. harpist, Carlos Salzedo. She became Principal Harpist with Ms. Loman is a Fellow of the Royal Conservatory and was the Toronto Symphony in 1960. -

CATHERINE ROBBIN) Mezzo-Soprano JOHN GREER) Piano

THE SCHOOL OF School of Musi c Recital Hall Saturday , 31 January 1987 MUSIC 8 :00 p. m. ' MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NEWFOUNDLAND CATHERINE ROBBIN) Mezzo-soprano JOHN GREER) Piano I The Blessed Virgin•s Expostulation Henry Purcell (1659-1695) I I An die Mus i k Franz Schubert Der Fischer (1797-1828) Der Konig in Thule Der Musensohn I I I The Mary Stuart Songs Robert Schumann Abschied von Fr ankr eich (1810-1856) Nach der Gebur t ihres Sohnes An die Konigin Elisabeth Abschied von de r Wel t Gebet INTERMISSION IV Chansons de Bi1itis Claude Debussy La Flute de Pan (1862-1918) La Chevelure Le Tombeau de s Na~ ade s v The House of Tomorrow John Greer (b. 1954 ) On Childr en The Whole Duty of Child:Pen : A Recitation Midnight Prayer Rhyme VI Iri sh Country Songs arr. Hughes The Ne xt Market Day ( 1882-1937) I Know Where I 'm Coin ' The Bard of Armagh The Lover 's Curse A Ballynure Ballad CATHERINE ROBBIN, Mezzo-soprano A "musician of rare sensitivity" with a stunning voice of unusual colour and richnes mezzo-soprano Catherine Robbin reinforces her reputation as a dedicated a extraordinarily gifted artist through her performances in opera, oratorio and recital. A top prize winner in the vocal competitions of Paris and Geneva, and the Gold Awa Winner at the Benson and Hedges International Competition in Great Britain, Miss Robb has been described as having "unquestionably one of the finest voices, in its range, th Canada has produced in decades". Highlights of the past season included performances of Messiah with the Montre Symphony, Berlioz' Les Nui ts d 'Ete with the National Ballet of Canada and Mozart Requiem with the National Arts Centre Orchestra. -

St John Smaller For

Early Music Vancouver john sawyer (1937-2017) board of directors Tonight’s performance is dedicated to the memory of John Sawyer (1937-2017). Tony Knox president For such a soft-spoken and Chris Guzy self-effacing gentleman, the vice president impact of John’s life and Spencer Corrigal cpa,ca work on the musical life of treasurer Vancouver and beyond has Sharon Kahn past president been loud and clear. Fran Watters secretary He was a member of the Stuart Bowyer very first undergraduate Sherrill Grace class in music at UBC, and, Ilia Korkh after studies elsewhere, Melody Mason returned as a faculty Tim Rendell cpa,ca member and became a Ingrid Söchting Vincent Tan passionate and popular teacher, with a focus on ÷ early music. He established Photo credit: Daryl Kahn Cline José Verstappen cm a Collegium Musicum, instigated the purchase of historical instruments and a library artistic director emeritus of music to play on them, and inspired in several generations of students an interest in ÷ period performance practice. A number of these went on to become core members of staff the Pacific Baroque Orchestra, to form their own ensembles, and to perform with early Matthew White music groups internationally.. executive & artistic director Nathan Lorch John’s primary role in establishing the Vancouver Society for Early Music (later Early business manager Alicia Hansen Music Vancouver), along with the summer courses they hosted at UBC, led to Vancouver production and summer programme director becoming something of a hotspot for early music performance and study. Jocelyn Peirce development coordinator The main thrust for establishing the Pacific Baroque Orchestra came from John, as did Laina Tanahara the name, as he had previously played concerts with a small group called the Pacific marketing & volunteer coordinator Baroque Ensemble.