SNOW's DREAM of RED CHINA on Rereading Red Star Over China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China's Propaganda in the United States During World War II

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 248 514 CS 208 471 AUTHOR Tsang, Kuo-jen - TITLE China's Propaganda in the United States during World War II. PUB DATE Aug 84 NOTE 44p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (67th, Gainesville, FL, August 5-8, . , 1984). PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) -- Speeches /Conference Papers (150) \N, EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Content Analysis; Cultural Images; Foreign`Countries; information Sources; *Media Research; News Reporting; *Propaganda; *Public Opinion; War; World History IDENTIFIERS *China; *World War II ABSTRACT Drawing data from a variety of sources, a study was undertaken to place China's propaganda activities in the United States during World War II into a historical perspective. Results showed that China's propaganda effortsconsisted of official and unofficial activities and activities directed toward overseas Chinese. The official activities were carried out by the Chinese News Service and its branch offices in various American cities under the direction of the Ministry of Information's International Department in Chungking. The unofficial activities Were carried out by both Chinese and Americans, including missionaries, business people, and newspaper reporters, and the activities ditected toward the overseas Chinese in the United States were undertaken for the purpose of collecting money and arousing patriotism. The propaganda program fell four phases, the first beginning with the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and directed at exposing Japanese atrocities. The second phase began with the withdrawal of the Chinese central government to inner China in late 1937, continued until the beginning of the European war in 1939, and concentrated on economic and political interests. -

CONTEMPORARY CHINA: a BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R Margins 0.9") by Lynn White

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R margins 0.9") by Lynn White This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of the seminars WWS 576a/Pol. 536 on "Chinese Development" and Pol. 535 on "Chinese Politics," as well as the undergraduate lecture course, Pol. 362; --to provide graduate students with a list that can help their study for comprehensive exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not too much should be made of this, because some such books may be too old for students' purposes or the subjects may not be central to present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan. Students with specific research topics should definitely meet Laird Klingler, who is WWS Librarian and the world's most constructive wizard. This list cannot cover articles, but computer databases can. Rosemary Little and Mary George at Firestone are also enormously helpful. Especially for materials in Chinese, so is Martin Heijdra in Gest Library (Palmer Hall; enter up the staircase near the "hyphen" with Jones Hall). Other local resources are at institutes run by Chen Yizi and Liu Binyan (for current numbers, ask at EAS, 8-4276). Professional bibliographers are the most neglected major academic resource at Princeton. -

The Darkest Red Corner Matthew James Brazil

The Darkest Red Corner Chinese Communist Intelligence and Its Place in the Party, 1926-1945 Matthew James Brazil A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Doctor of Philosophy Department of Government and International Relations Business School University of Sydney 17 December 2012 Statement of Originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted previously, either in its entirety or substantially, for a higher degree or qualifications at any other university or institute of higher learning. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources has been acknowledged. Matthew James Brazil i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Before and during this project I met a number of people who, directly or otherwise, encouraged my belief that Chinese Communist intelligence was not too difficult a subject for academic study. Michael Dutton and Scot Tanner provided invaluable direction at the very beginning. James Mulvenon requires special thanks for regular encouragement over the years and generosity with his time, guidance, and library. Richard Corsa, Monte Bullard, Tom Andrukonis, Robert W. Rice, Bill Weinstein, Roderick MacFarquhar, the late Frank Holober, Dave Small, Moray Taylor Smith, David Shambaugh, Steven Wadley, Roger Faligot, Jean Hung and the staff at the Universities Service Centre in Hong Kong, and the kind personnel at the KMT Archives in Taipei are the others who can be named. Three former US diplomats cannot, though their generosity helped my understanding of links between modern PRC intelligence operations and those before 1949. -

"Thought Reform" in China| Political Education for Political Change

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1979 "Thought reform" in China| Political education for political change Mary Herak The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Herak, Mary, ""Thought reform" in China| Political education for political change" (1979). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1449. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1449 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 THIS IS AN UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT IN WHICH COPYRIGHT SUB SISTS, ANY FURTHER REPRINTING OF ITS CONTENTS MUST BE APPROVED BY THE AUTHOR. MANSFIELD LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA DATE: 19 7 9 "THOUGHT REFORM" IN CHINA: POLITICAL EDUCATION FOR POLITICAL CHANGE By Mary HeraJc B.A. University of Montana, 1972 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OP MONTANA 1979 Approved by: Graduat e **#cho o1 /- 7^ Date UMI Number: EP34293 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

The Life and Works of Philip J. Jaffe: a Foreigner's Foray

THE LIFE AND WORKS OF PHILIP J. JAFFE: A FOREIGNER’S FORAY INTO CHINESE COMMUNISM Patrick Nichols “…the capitalist world is divided into two rival sectors, the one in favor of peace and the status quo, and the other the Fascist aggressors and provokers of a new world war.” These words spoken by Mao Tse Tung to Philip J. Jaffe in a confidential interview. Although China has long held international relations within its Asian sphere of influence, the introduction of a significant Western persuasion following their defeats in the Opium Wars was the first instance in which China had been subservient to the desires of foreigners. With the institution of a highly westernized and open trading policy per the wishes of the British, China had lost the luster of its dynastic splendor and had deteriorated into little more than a colony of Western powers. Nevertheless, as China entered the 20th century, an age of new political ideologies and institutions began to flourish. When the Kuomintang finally succeeded in wrestling control of the nation from the hands of the northern warlords following the Northern Expedition1, it signaled a modern approach to democratizing China. However, as the course of Chinese political history will show, the KMT was a morally weak ruling body that appeased the imperial intentions of the Japanese at the cost of Chinese citizens and failed to truly assert its political legitimacy during it‟s almost ten year reign. Under these conditions, a radical and highly determined sect began to form within the KMT along with foreign assistance. The party held firmly on the idea of general welfare, but focused mostly on the rights of the working class and student nationalists. -

The Media and Sino-American Rapprochement, 1963-1972

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2013 Reading The eT a Leaves: The ediM a And Sino- American Rapprochement, 1963-1972 Guolin Yi Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons, History Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Yi, Guolin, "Reading The eT a Leaves: The eM dia And Sino-American Rapprochement, 1963-1972" (2013). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 719. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. READING THE TEA LEAVES: THE MEDIA AND SINO-AMERICAN RAPPROCHEMENT, 1963-1972 by GUOLIN YI DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2013 MAJOR: HISTORY Approved by: ____________________________________ Advisor Date ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ! ! ! COPYRIGHT BY GUOLIN YI 2013 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to my parents, Youju Yi and Lanying Zhao, my siseter Fenglin Yi, and my wife Lin Zhang. ! ii! ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am sincerely and heartily grateful to my advisor Melvin Small, who has lighted my way through the graduate study at Wayne State. I am sure this dissertation would not have been possible without his quality guidance, warm encouragement, and conscientious editing. I would also like to thank other members of my dissertation committee: Professors Alex Day, Aaron Retish, Liette Gidlow, and Yumin Sheng for their helpful suggestions. -

Foreigners Under Mao

Foreigners under Mao Western Lives in China, 1949–1976 Beverley Hooper Hong Kong University Press Th e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2016 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8208-74-6 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Cover images (clockwise from top left ): Reuters’ Adam Kellett-Long with translator ‘Mr Tsiang’. Courtesy of Adam Kellett-Long. David and Isobel Crook at Nanhaishan. Courtesy of Crook family. George H. W. and Barbara Bush on the streets of Peking. George Bush Presidential Library and Museum. Th e author with her Peking University roommate, Wang Ping. In author’s collection. E very eff ort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. Th e author apologizes for any errors or omissions and would be grateful for notifi cation of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgements vii Note on transliteration viii List of abbreviations ix Chronology of Mao’s China x Introduction: Living under Mao 1 Part I ‘Foreign comrades’ 1. -

Kampen MAO ZEDONG, ZHOU ENLAI and the CHINESE COMMUNIST

Kampen MAO ZEDONG, ZHOU ENLAI AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE CHINESE COMMUNIST LEADERSHIP MAO ZEDONG, ZHOU ENLAI Thomas Kampen MAO ZEDONG, ZHOU ENLAI AND THE CHINESE COMMUNIST LEADERSHIP NIAS AND THE EVOLUTION OF This book analyses the power struggles within the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party between 1931, when several Party leaders left Shanghai and entered the Jiangxi Soviet, and 1945, by which time Mao Zedong, Liu THE CHINESE COMMUNIST Shaoqi and Zhou Enlai had emerged as senior CCP leaders. In 1949 they established the People's Republic of China and ruled it for several decades. LEADERSHIP Based on new Chinese sources, the study challenges long-established views that Mao Zedong became CCP leader during the Long March (1934–35) and that by 1935 the CCP was independent of the Comintern in Moscow. The result is a critique not only of official Chinese historiography but also of Western (especially US) scholarship that all future histories of the CCP and power struggles in the PRC will need to take into account. “Meticulously researched history and a powerful critique of a myth that has remained central to Western and Chinese scholarship for decades. Kampen’s study of the so-called 28 Bolsheviks makes compulsory reading for anyone Thomas Kampen trying to understand Mao’s (and Zhou Enlai’s!) rise to power. A superb example of the kind of revisionist writing that today's new sources make possible, and reminder never to take anything for granted as far as our ‘common knowledge’ about the history of the Chinese Communist Party is concerned.” – Michael Schoenhals, Director, Centre for East and Southeast Asian Studies, Lund University, Sweden “Thomas Kampen has produced a work of exceptional research which, through the skillful use of recently available Chinese sources, questions the accepted wisdom about the history of the leadership of the CCP. -

SNOW, Edgar Parks Aìdéjiā Pàkèsī Sīnuò 埃德加帕克斯斯诺 1905–1972 American Author and Journalist

◀ Sixteen Kingdoms Comprehensive index starts in volume 5, page 2667. SNOW, Edgar Parks Aìdéjiā Pàkèsī Sīnuò 埃德加帕克斯斯诺 1905–1972 American author and journalist The work of Edgar Parks Snow helped pro- career in advertising. He also studied journalism briefly mote normalization of the U.S.-China rela- at Columbia University. After making eight hundred dol- tionship. As a journalist, Snow is known as the lars from a modest stock investment, Snow decided to see first and last foreign journalist to interview the world. In 1928 he arrived in Shanghai and met his des- tiny: China, which became his home for the next twelve Chinese leader Mao Zedong. As an author, years. His travels took him throughout Asia, including Snow is recognized for his book Red Star over the Philippines (where he lived for two years), Indochina, China, which gave insight into the Chinese Burma, and India. He also lived just less than two years Communist Party and Red Army leaders. in Russia. In Shanghai, Snow took a job at the China Weekly Review. Given an assignment to write about tourist at- dgar Snow was an American journalist who tractions of town and cities along the Chinese railways, authored eleven books and worked as a highly Snow was able to travel outside the foreign concessions successful foreign correspondent during World of Shanghai and to see things other Westerns could not War II. His most famous publication, Red Star over China see. He was appalled by China’s poverty: Westerners re- (1937), provided the West with its first glimpse of the revo- ceived special privileges, as did Chinese city dwellers, but lutionary Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its Red the vast majority of rural Chinese were trapped in dire Army leaders. -

Media Resources

PREPARATION FOR UNDERSTANDING Preparation includes learning as much as possible about the country and culture of China before you depart. Below is a partial list of books and films that are both enjoyable and educational. Most of these works, and more, are available at your local library, bookstore, or directly from the publisher. History Fanshen: A Documentary of Revolution in a Chinese Village by William Hinton (Vintage, 1966) This is a classic account of the Communist Revolution and subsequent reforms in China. William Hinton stayed in the liberated area of North China from 1947-1953, a period spanning China before, during, and after the revolution. He served as a tractor technician and teacher, living with the peasants of Long Bow village and experiencing the Revolution with them. Red Star Over China by Edgar Snow (Bantam Books, 1978) This is a classic book about China. Originally written in 1938, it is based on Edgar Snow’s experience as a young journalist going behind enemy lines to interview the communist leadership in Yenan at the end of the Long March. Contains interviews with Mao at a time when some thought him dead and very few predicted that he would emerge as the leader of a victorious communist state. Snow writes with great sympathy for the communists. As a result, the book is well known and loved by the Chinese even today. China: Alive in a Bitter Sea by Fox Butterfield (Bantam Books, 1983) This is a thought-provoking book about China immediately following the Cultural Revolution. Written by a Chinese-speaking correspondent of The New York Times, it contains many interviews with persons who lived through and suffered during the 1966-1976 period. -

Searchable PDF Format

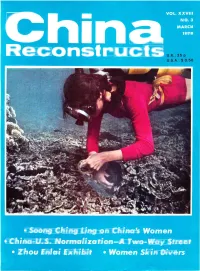

7- a :DL' It- {ol :-_ T[TfolIF AYil Ere iIfrE'II rIjIe irq;t tI.a' l.li iT]Etf;.r a 1t tIo T a I .l a /,a l '^'l o ,i6NIj IET=T 4 ril ol it , f' z 7l tlfrF- 'q CH RECO NSTRUCTS INA PUBLI5HED MONTHLY IN ENGLISH, FRENCH; SPANISH, ARABIC AND BIMONTHLY IN GERMAN BY THE CHINA WELFARE INSTITUIE t\D I ii. (sooNc cHtNG L|NG, CHATRMAN) voL. xxvilt No. s MARCH I979 CONTENIS Our Postbag Modernization and Women Cartoons by Wang Letian a Soong Ching Ling, o Vice-Choir- Across the Land: New Shanghai General mon ol the Notionol People's Con- Petrochemical Works 4 gress, Honorory President ol the No- China's Women in Our New Long March tionol Women's Federotion ond Soong Ching Ling 6 plominent for o holl century in the women's movement, The Women Meet (poem) Rewi Alley 11 tells obout the present roles of Chinese women in Norma ization Has a History A Two-Way the society os well os ot home (p. 6). Street Ma Haide - 12 And on interview with luo Qiong, Record of a Fighting Life Exhibition on Vice-Choirmon of the Notionol Wom- Zhou - 19 Enlai Su Donghai en's Federotion, who soys the tor- Qingdao Port City and Summer Resort get - is not men but complete Zeng Xiang0ing 26 emoncipotion through sociolist pro- Things Chinese: Laoshan Mineral Water e.) gress (p. 33). The Women's Movement in China-An lnter- Pages 6 and 33 view with Luo Qiong 'The Donkey Seller' Bao Wenqing 37 Wood Carving Continues Fu Tianchou 42 The Record of New Spelling ior Names and Places 45 a Fighting Life The Silence Explodes A Play about the Tian An Men Incident- Ren Zhiji and A tour through E^^ t;^^^: I dtl Jldoal 46 on exhibition Stamps ot New China Arts and Crafts 49 on the lote Cultural Notes: 'Women Skin Divers', a Color Premier Zhou Documentary Li Wenbin 50 Enloi. -

Edgar Parks Snow Collection Finding Aid (PDF)

July 5, 1994 revised April 19, 2010 UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI-KANSAS CITY Edgar Parks Snow (1905-1972) Papers KC:19/1/00, 4, 8, 9, 11, 12, 16, 18 1928-1972 (includes posthumous materials, 1972-1982) 718 folders, 4 scrapbooks, audio tapes, motion picture film, and photographs (173 folders) PROVENANCE The main body of the Edgar Snow Papers was donated by his widow, Lois Wheeler Snow, to the University of Missouri in 1986. Ownership of the collection passed to the University Archives in increments over several years with the last installment transferred in 1989. Additional materials from Mrs. Snow have been received as recently as 1994. BIOGRAPHY Edgar Parks Snow was born in Kansas City, Missouri, on July 19, 1905. He received his education locally and briefly attended the University of Missouri School of Journalism in Columbia. At 19, he left college and moved to New York City to embark on a career in advertising. In 1928, after making a little money in the stock market, he left to travel and write of his journeys around the world. He arrived in Shanghai July 6, 1928, and was to remain in China for the next thirteen years. His first job was with The China Weekly Review in Shanghai. Working as a foreign correspondent, he wrote numerous articles for many leading American and English newspapers and periodicals. In 1932, he married Helen (Peg) Foster, (also known as Nym Wales). The following year, the couple settled in Beijing where Snow taught at Yenching University. © University of Missouri-Kansas City Archives 5100 Rockhill Road, Kansas City, MO 64110-2499 Edgar Parks Snow Papers Inventory 04/19/2010 Page ii Edgar Snow spent part of the early 1930’s traveling over much of China on assignment for the Ministry of Railways of the National Government.