Women, Peace and Security and Access to Justice in Newly and Recently Recovered Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South and Central Somalia Security Situation, Al-Shabaab Presence, and Target Groups

1/2017 South and Central Somalia Security Situation, al-Shabaab Presence, and Target Groups Report based on interviews in Nairobi, Kenya, 3 to 10 December 2016 Copenhagen, March 2017 Danish Immigration Service Ryesgade 53 2100 Copenhagen Ø Phone: 00 45 35 36 66 00 Web: www.newtodenmark.dk E-mail: [email protected] South and Central Somalia: Security Situation, al-Shabaab Presence, and Target Groups Table of Contents Disclaimer .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction and methodology ......................................................................................................................... 4 Abbreviations..................................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Security situation ....................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1. The overall security situation ........................................................................................................ 7 1.2. The extent of al-Shabaab control and presence.......................................................................... 10 1.3. Information on the security situation in selected cities/regions ................................................ 11 2. Possible al-Shabaab targets in areas with AMISOM/SNA presence ....................................................... -

Bay Bakool Rural Baseline Analysis Report

Technical Series Report No VI. !" May 20, 2009 Livelihood Baseline Analysis Bay and Bakool Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit - Somalia Box 1230, Village Market Nairobi, Kenya Tel: 254-20-4000000 Fax: 254-20-4000555 Website: www.fsnau.org Email: [email protected] Technical and Funding Agencies Managerial Support European Commission FSNAU Technical Series Report No VI. 19 ii Issued May 20, 2009 Acknowledgements These assessments would not have been possible without funding from the European Commission (EC) and the US Office of Foreign Disaster and Assistance (OFDA). FSNAU would like to also thank FEWS NET for their funding contributions and technical support made by Mohamed Yusuf Aw-Dahir, the FEWS NET Representative to Soma- lia, and Sidow Ibrahim Addow, FEWS NET Market and Trade Advisor. Special thanks are to WFP Wajid Office who provided office facilities and venue for planning and analysis workshops prior to, and after fieldwork. FSNAU would also like to extend special thanks to the local authorities and community leaders at both district and village levels who made these studies possible. Special thanks also to Wajid District Commission who was giving support for this assessment. The fieldwork and analysis would not have been possible without the leading baseline expertise and work of the two FSNAU Senior Livelihood Analysts and the FSNAU Livelihoods Baseline Team consisting of 9 analysts, who collected and analyzed the field data and who continue to work and deliver high quality outputs under very difficult conditions in Somalia. This team was led by FSNAU Lead Livelihood Baseline Livelihood Analyst, Abdi Hussein Roble, and Assistant Lead Livelihoods Baseline Analyst, Abdulaziz Moalin Aden, and the team of FSNAU Field Analysts and Consultants included, Ahmed Mohamed Mohamoud, Abdirahaman Mohamed Yusuf, Abdikarim Mohamud Aden, Nur Moalim Ahmed, Yusuf Warsame Mire, Abdulkadir Mohamed Ahmed, Abdulkadir Mo- hamed Egal and Addo Aden Magan. -

Mogadishu IDP Influx 28 October 2011 2011 Has Witnessed an Unprecedented Arrival of Idps Into Mogadishu Due to Drought Related Reasons

UNHCR BO Somalia, Nairobi Mogadishu IDP Influx 28 October 2011 2011 has witnessed an unprecedented arrival of IDPs into Mogadishu due to drought related reasons. While the largest influx of IDP s occurred in January 2011, trends indicate that since March, the rate of influx has been steadily increasing. Based on IASC Po pulation Movement Tracking (PMT) data, this analysis aims to identify the key areas receiving IDPs in Mogadishu as well as the source of displacement this year . 1st Quarter 2nd Quarter 3rd Quarter 4th Quarter January to March 2011 April to June 2011 July to September 2011 1 October, 2011 to 28 October 2011 Total IDP Arrivals in Mogadishu 31,400 Total IDP Arrivals in Mogadishu 8,500 Total IDP Arrivals in Mogadishu 35,800 From other areas of Somalia, not including From other areas of Somalia, not including From other areas of Somalia, not including Total IDP Arrivals in Mogadishu 6,800 displacement within Mogadishu. displacement within Mogadishu. displacement within Mogadishu. From other areas of Somalia, not including displacement within Mogadishu. Arrivals by Month Arrivals by Month Arrivals by Month Arrivals by Month 24,200 27,500 6,500 5,700 6,300 6,800 800 1,100 1,700 2,000 January February March April May June July August September October Source of Displacement Reason for Displacement Source of Displacement Reason for Displacement Source of Displacement Reason for Displacement Source of Displacement Where are these IDPs coming from? Why did these people travel to Mogadishu? Why did these people travel to Mogadishu? Why did these people travel to Mogadishu? Where are these IDPs coming from? Where are these IDPs coming from? Where are these IDPs coming from? Eviction During the first quarter, 2,200 people were Reason for Displacement 0 0 reported to have been evicted from IDP settlements 0 Eviction 100 people were reported to have been evicted from 0 Eviction 1 - 99 in the Afgooye corridor and moved to Mogadishu. -

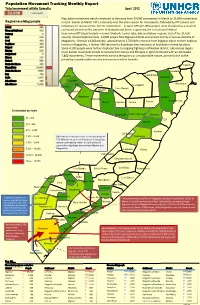

Population Movement Tracking Monthly Report

Population Movement Tracking Monthly Report Total movement within Somalia April 2012 33,000 nationwide Population movement trends continued to decrease from 39,000 movements in March to 33,000 movements Region receiving people in April. Similar to March 2012, insecurity was the main reason for movements, followed by IDP returns and Region People Awdal 400 temporary or seasonal cross border movements. In April, 65% (21,000 people) were displaced as a result of Woqooyi Galbeed 500 continued armed conflict between Al Shabaab and forces supporting the Transitional Federal Sanaag 0 Government(TFG) particularly in Lower Shabelle, Lower Juba, Bay and Bakool regions. Out of the 21,000 Bari 200 security related displacements, 14,000 people fled Afgooye district and arrived mainly in various districts of Sool 400 Mogadishu. Of these 14,000 people, approximately 3,700 IDPs returned from Afgooye closer to their habitual Togdheer 100 homes in Mogadishu, a further 590 returned to Baydhaba after cessation of hostilities in these locations. Nugaal 400 Some 4,100 people were further displaced due to ongoing fighting in Afmadow district, Juba Hoose region. Mudug 500 Cross border movement trends to Somalia from Kenya and Ethiopia in April continued with an estimated Galgaduud 0 2,800 movements. These movements are of a temporary or unsustainable nature, primarily due to the Hiraan 200 Bakool 400 prevailing unpredictable security environment within Somalia. Shabelle Dhexe 300 Caluula Mogadishu 20,000 Shabelle Hoose 1,000 Qandala Bay 700 Zeylac Laasqoray Gedo 3,200 Bossaso Juba Dhexe 100 Lughaye Iskushuban Juba Hoose 5,300 Baki Ceerigaabo Borama Berbera Ceel Afweyn Sheikh Gebiley Hargeysa Qardho Odweyne Bandarbeyla Burco Caynabo Xudun Taleex Estimated arrivals Buuhoodle Laas Caanood Garoowe 30 - 250 Eyl Burtinle 251 - 500 501 - 1,000 Jariiban Goldogob 1,001 - 2,500 IDPs who were displaced due to tensions between Gaalkacyo TFG-Allied forces and the Al Shabaab in Baydhaba 2,501 - 5,000 district continued to return. -

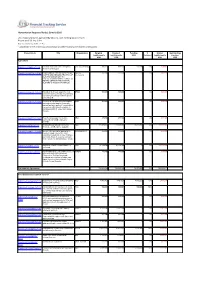

With Funding Status of Each Report As

Humanitarian Response Plan(s): Somalia 2016 List of appeal projects (grouped by Cluster), with funding status of each Report as of 23-Sep-2021 http://fts.unocha.org (Table ref: R3) Compiled by OCHA on the basis of information provided by donors and recipient organizations. Project Code Title Organization Original Revised Funding % Unmet Outstanding requirements requirements USD Covered requirements pledges USD USD USD USD Agriculture SOM-16/A/84942/5110 Puntland and Lower Juba Emergency VSF (Switzerland) 998,222 998,222 588,380 59% 409,842 0 Animal Health Support SOM-16/A/86501/15092 PROVISION OF FISHING INPUTS FOR SAFUK- 352,409 352,409 0 0% 352,409 0 YOUTHS AND MEN AND TRAINING OF International MEN AND WOMEN ON FISH PRODUCTION AND MAINTENANCE OF FISHING GEARS IN THE COASTAL REGIONS OF MUDUG IN SOMALIA. SOM-16/A/86701/14592 Integrated livelihoods support to most BRDO 500,000 500,000 0 0% 500,000 0 vulnerable conflict affected 2850 farming and fishing households in Marka district Lower Shabelle. SOM-16/A/86746/14852 Provision of essential livelihood support HOD 500,000 500,000 0 0% 500,000 0 and resilience building for Vulnerable pastoral and agro pastoral households in emergency, crisis and stress phase in Kismaayo district of Lower Juba region, Somalia SOM-16/A/86775/17412 Food Security support for destitute NRO 499,900 499,900 0 0% 499,900 0 communities in Middle and Lower Shabelle SOM-16/A/87833/123 Building Household and Community FAO 111,805,090 111,805,090 15,981,708 14% 95,823,382 0 Resilience and Response Capacity SOM-16/A/88141/17597 Access to live-saving for population in SHARDO Relief 494,554 494,554 0 0% 494,554 0 emergency and crises of the most vulnerable households in lower Shabelle and middle Shabelle regions, and build their resilience to withstand future shocks. -

Somalia Health Cluster Bulletin #29

Somalia Health Cluster Bulletin #29 Photo: WHO November 2009 The Somalia Health Cluster Bulletin pro- vides an overview of the health activities conducted by the health cluster partners operating in Somalia. The Health Cluster Bulletin is issued on a monthly basis; and is available online at www.emro.who.int/somalia/healthcluster Contributions are to be sent to Newly established Bu’aale field hospital expanded health services [email protected] to the conflict-affected population of Lower and Middle Jubba HIGHLIGHTS CAP 2010 will be launched on 3 December in Nairobi. 174 projects coordinated by the 9 clusters and enabling programmes appealing for a total of US$ 689 million to address the most urgent humanitarian needs in Somalia in 2010 considering the feasibility of implementation. More than 350 health workers were trained this month on topics including AWD/cholera case management; malaria prevention, diagnosis and treatment; emergency blood safety; sexual and gender based violence; and family planning methods and basic emergency obstetric care. SITUATION OVERVIEW Conflict According to OCHA1, 12 international staff members of the UN and an international NGO were relocated from Bu’aale (Middle Jubba) as renewed conflict spread in the region. Admissions and inpatients in Kismaayo hospital have gradually reduced early this month before fighting increased again on 22 November around Kismaayo (Lower Jubba). Through reports from health facilities and other stakeholders, WHO estimates a total of 670 peo- ple wounded and an estimated 180 killed Photo: SORDES since the beginning of October in Middle and Lower Jubba regions, mostly between Kis- maayo and Afmadow. -

Cash Based Programming in Emergencies East Africa Region

CASH BASED PROGRAMMING IN EMERGENCIES EAST AFRICA REGION JANUARY-DECEMBER 2017 REPORT ACRONYMS ADH......................................Aktion Deutschland Hilft ANCP..................................Australian NGO Cooperation Program DEC.......................................Disaster Emergency Committee FAO.........................................Food and Agriculture Organization GAC......................................Global Affairs Canada NFIs.......................................Non-Food Items SDC.......................................Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation SIDA.....................................Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency SHO......................................Samenwerkende Hulporganisaties UNDP.................................United Nations Development Programme UNHCR.............................United Nations High Commission for Refugees UNOCHA.......................UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs USAID-FFP....................United States Agency for International Development WFP......................................World Food Programme World Vision is a Christian relief, development and advocacy organisation dedicated to working with children, families and communities to overcome poverty and injustice. Inspired by our Christian values, we are dedicated to working with the world’s most vulnerable people. We serve all people regardless of religion, race, ethnicity or gender. © 2018 World Vision International Contributors: Christopher Hoffman, Belete Temesgen, -

Somalia: Window of Opportunity for Addressing One of the World's Worst Internal Displacement Crises 9

SOMALIA: Window of opportunity for addressing one of the world’s worst internal displacement crises A profile of the internal displacement situation 10 January 2006 This Internal Displacement Profile is automatically generated from the online IDP database of the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). It includes an overview of the internal displacement situation in the country prepared by the IDMC, followed by a compilation of excerpts from relevant reports by a variety of different sources. All headlines as well as the bullet point summaries at the beginning of each chapter were added by the IDMC to facilitate navigation through the Profile. Where dates in brackets are added to headlines, they indicate the publication date of the most recent source used in the respective chapter. The views expressed in the reports compiled in this Profile are not necessarily shared by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. The Profile is also available online at www.internal-displacement.org. About the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, established in 1998 by the Norwegian Refugee Council, is the leading international body monitoring conflict-induced internal displacement worldwide. Through its work, the Centre contributes to improving national and international capacities to protect and assist the millions of people around the globe who have been displaced within their own country as a result of conflicts or human rights violations. At the request of the United Nations, the Geneva-based Centre runs an online database providing comprehensive information and analysis on internal displacement in some 50 countries. Based on its monitoring and data collection activities, the Centre advocates for durable solutions to the plight of the internally displaced in line with international standards. -

S.No Region Districts 1 Awdal Region Baki

S.No Region Districts 1 Awdal Region Baki District 2 Awdal Region Borama District 3 Awdal Region Lughaya District 4 Awdal Region Zeila District 5 Bakool Region El Barde District 6 Bakool Region Hudur District 7 Bakool Region Rabdhure District 8 Bakool Region Tiyeglow District 9 Bakool Region Wajid District 10 Banaadir Region Abdiaziz District 11 Banaadir Region Bondhere District 12 Banaadir Region Daynile District 13 Banaadir Region Dharkenley District 14 Banaadir Region Hamar Jajab District 15 Banaadir Region Hamar Weyne District 16 Banaadir Region Hodan District 17 Banaadir Region Hawle Wadag District 18 Banaadir Region Huriwa District 19 Banaadir Region Karan District 20 Banaadir Region Shibis District 21 Banaadir Region Shangani District 22 Banaadir Region Waberi District 23 Banaadir Region Wadajir District 24 Banaadir Region Wardhigley District 25 Banaadir Region Yaqshid District 26 Bari Region Bayla District 27 Bari Region Bosaso District 28 Bari Region Alula District 29 Bari Region Iskushuban District 30 Bari Region Qandala District 31 Bari Region Ufayn District 32 Bari Region Qardho District 33 Bay Region Baidoa District 34 Bay Region Burhakaba District 35 Bay Region Dinsoor District 36 Bay Region Qasahdhere District 37 Galguduud Region Abudwaq District 38 Galguduud Region Adado District 39 Galguduud Region Dhusa Mareb District 40 Galguduud Region El Buur District 41 Galguduud Region El Dher District 42 Gedo Region Bardera District 43 Gedo Region Beled Hawo District www.downloadexcelfiles.com 44 Gedo Region El Wak District 45 Gedo -

PROTECTION of CIVILIANS REPORT Building the Foundation for Peace, Security and Human Rights in Somalia

UNSOM UNITED NATIONS ASSISTANCE MISSION IN SOMALIA PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS REPORT Building the Foundation for Peace, Security and Human Rights in Somalia 1 JANUARY 2017 – 31 DECEMBER 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................1 Methodology ...................................................................................................................................7 Civilian Casualties Attributed to non-State Actors ....................................................................9 A. Al Shabaab .............................................................................................................................9 B. Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama ..........................................................................................................16 C. Clan Militia ..........................................................................................................................17 D. The Islamic State Affiliated Group ......................................................................................17 Civilian Casualties Attributed to State Actors and other Actors ............................................18 A. Somali National Army ...................................................................................................18 B. Somali Police Force .......................................................................................................21 C. The National Intelligence Security Agency -

Detailed Site Assessment (DSA) Afgooye District, Lower Shabelle Region, Somalia

Detailed Site Assessment (DSA) February 2020 Afgooye district, Lower Shabelle region, Somalia SOMALIA CONTEXT METHODOLOGY Somalia continues to experience recurrent Primary data collection employed a Key To provide a local, context-specific overview and droughts, floods, and armed conflict, driving Informant (KI) methodology with KI interviews allow more targeted responses, this factsheet large-scale displacement. The high levels conducted by REACH enumerators in locations presents a summary of findings of assessed of displacement have resulted in fluctuating directly accessible by REACH Field Officers settlements in Afgooye district only. population estimates of Internally Displaced (FOs) and by CCCM partner organizations. Persons (IDPs) in both formal and informal Targeted urban areas within districts were The nation-wide, sectoral factsheets are available settlements, thereby complicating the provision determined based on a secondary literature here. of basic services to address their needs. review of previous assessments conducted on Assessment information IDP populations1. Following the identification The Detailed Site Assessment (DSA) was of target urban areas, REACH located IDP Total assessed sites initiated in coordination with the Camp settlements through contacting the lowest level 44 Coordination and Camp Management (CCCM) of governance2 in each area to identify the Displacement Cluster in order to provide the humanitarian locations of IDP settlements. community with up-to-date information on Total number of IDPs households the location of IDP sites, the conditions and The severity calculation for the third round of the arriving into a new settlement: 949 capacity of the sites, and an estimate of the DSA was developed in close consultation with severity of humanitarian needs of residents. -

Somalia Hagaa Season Floods Update 2 As of 26 July 2020

Somalia Hagaa Season Floods Update 2 As of 26 July 2020 Highlights • Flash and riverine floods have since late June affected an estimated 191,800 people in Hirshabelle, South West and Jubaland states as well as Banadir region. • Among those affected, about 124,200 people have been displaced from their homes. Another 5,000 peope are at risk of further displacement in Jowhar, Middle Shabelle. • Since May, an estimated 149,000 hectares of farmland have been damaged by floods in 100 villages in Jowhar, Mahaday and Balcad districts, Middle Shabelle region. • Humanitarian partners have scaled up responses, but major gaps remain particularly in regard to food, WASH, shelter and non-food items, health services and protection assistance. Situation overview The number of people affected by flash and riverine floods since late June in Hirshabelle, South West, Jubaland states and Banadir region has risen to 191,800, of whom 124,200 people have been displaced from their homes, according to various rapd asessments. Hirshabelle and South West States are the worst affected, accounting for nearly 91 per cent of the caseload (164,000 people). Humanitarian needs are rising among those affected, even as partners ramp up assistance. The floods have been triggered by heavy downpours during the current Hagaa ‘dry’ season. SWALIM1 forecasts that flooding in the middle and lower reaches of the Shabelle will continue in the coming week especially in Jowhar town and surrounding areas, due to anticipated moderate to heavy rains. In Hirshabelle, flash and riverine floods displaced at least 66,000 people and damaged 33,000 hectares of farmland in Balcad district, Middle Shabelle region, between 24 June and 15 July, according to joint assessment conducted on 21 July by humanitarian partners and authorities.