Mp201763.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epigenetic Regulation of the PTEN–AKT–RAC1 Axis by G9a Is Critical for Tumor Growth in Alveolar Rhabdomyosarcoma Akshay V

Published OnlineFirst March 4, 2019; DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2676 Cancer Molecular Cell Biology Research Epigenetic Regulation of the PTEN–AKT–RAC1 Axis by G9a Is Critical for Tumor Growth in Alveolar Rhabdomyosarcoma Akshay V. Bhat1, Monica Palanichamy Kala1, Vinay Kumar Rao1, Luca Pignata2, Huey Jin Lim3, Sudha Suriyamurthy1, Kenneth T.Chang4,Victor K. Lee3, Ernesto Guccione2, and Reshma Taneja1 Abstract Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (ARMS) is an aggressive suppressor PTEN was a direct target gene of G9a. G9a pediatric cancer with poor prognosis. As transient and stable repressed PTEN expression in a methyltransferase activity– modifications to chromatin have emerged as critical dependent manner, resulting in increased AKT and RAC1 mechanisms in oncogenic signaling, efforts to target epige- activity. Re-expression of constitutively active RAC1 in G9a- netic modifiers as a therapeutic strategy have accelerated in deficient tumor cells restored oncogenic phenotypes, demon- recent years. To identify chromatin modifiers that sustain strating its critical functions downstream of G9a. Collectively, tumor growth, we performed an epigenetic screen and our study provides evidence for a G9a-dependent epigenetic found that inhibition of lysine methyltransferase G9a sig- program that regulates tumor growth and suggests targeting nificantly affected the viability of ARMS cell lines. Targeting G9a as a therapeutic strategy in ARMS. expression or activity of G9a reduced cellular proliferation and motility in vitro and tumor growth in vivo.Transcrip- Significance: These findings demonstrate that RAC1 is an tome and chromatin immunoprecipitation–sequencing effector of G9a oncogenic functions and highlight the poten- analysis provided mechanistic evidence that the tumor- tial of G9a inhibitors in the treatment of ARMS. -

DNA Methylation of GHSR, GNG4, HOXD9 and SALL3 Is a Common Epigenetic Alteration in Thymic Carcinoma

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY 56: 315-326, 2020 DNA methylation of GHSR, GNG4, HOXD9 and SALL3 is a common epigenetic alteration in thymic carcinoma REINA KISHIBUCHI1, KAZUYA KONDO1, SHIHO SOEJIMA1, MITSUHIRO TSUBOI2, KOICHIRO KAJIURA2, YUKIKIYO KAWAKAMI2, NAOYA KAWAKITA2, TORU SAWADA2, HIROAKI TOBA2, MITSUTERU YOSHIDA2, HIROMITSU TAKIZAWA2 and AKIRA TANGOKU2 1Department of Oncological Medical Services, Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Tokushima University, Tokushima 770-8509; 2Department of Thoracic, Endocrine Surgery and Oncology, Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Tokushima University, Tokushima 770-8503, Japan Received August 17, 2019; Accepted October 25, 2019 DOI: 10.3892/ijo.2019.4915 Abstract. Thymic epithelial tumors comprise thymoma, promoter methylation of the 4 genes was not significantly thymic carcinoma and neuroendocrine tumors of the thymus. higher in advanced-stage tumors than in early-stage tumors in Recent studies have revealed that the incidence of somatic all thymic epithelial tumors. Among the 4 genes, relapse-free non‑synonymous mutations is significantly higher in thymic survival was significantly worse in tumors with a higher DNA carcinoma than in thymoma. However, limited information methylation than in those with a lower DNA methylation in all is currently available on epigenetic alterations in these types thymic epithelial tumors. Moreover, relapse-free survival was of cancer. In this study, we thus performed genome-wide significantly worse in thymomas with a higher DNA methyla- screening of aberrantly methylated CpG islands in thymoma tion of HOXD9 and SALL3 than in those with a lower DNA and thymic carcinoma using Illumina HumanMethylation450 methylation. On the whole, the findings of this study indicated K BeadChip. We identified 92 CpG islands significantly that the promoter methylation of cancer-related genes was hypermethylated in thymic carcinoma in relation to thymoma significantly higher in thymic carcinoma than in thymoma and and selected G protein subunit gamma 4 (GNG4), growth the thymus. -

Supplemental Information to Mammadova-Bach Et Al., “Laminin Α1 Orchestrates VEGFA Functions in the Ecosystem of Colorectal Carcinogenesis”

Supplemental information to Mammadova-Bach et al., “Laminin α1 orchestrates VEGFA functions in the ecosystem of colorectal carcinogenesis” Supplemental material and methods Cloning of the villin-LMα1 vector The plasmid pBS-villin-promoter containing the 3.5 Kb of the murine villin promoter, the first non coding exon, 5.5 kb of the first intron and 15 nucleotides of the second villin exon, was generated by S. Robine (Institut Curie, Paris, France). The EcoRI site in the multi cloning site was destroyed by fill in ligation with T4 polymerase according to the manufacturer`s instructions (New England Biolabs, Ozyme, Saint Quentin en Yvelines, France). Site directed mutagenesis (GeneEditor in vitro Site-Directed Mutagenesis system, Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France) was then used to introduce a BsiWI site before the start codon of the villin coding sequence using the 5’ phosphorylated primer: 5’CCTTCTCCTCTAGGCTCGCGTACGATGACGTCGGACTTGCGG3’. A double strand annealed oligonucleotide, 5’GGCCGGACGCGTGAATTCGTCGACGC3’ and 5’GGCCGCGTCGACGAATTCACGC GTCC3’ containing restriction site for MluI, EcoRI and SalI were inserted in the NotI site (present in the multi cloning site), generating the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. The SV40 polyA region of the pEGFP plasmid (Clontech, Ozyme, Saint Quentin Yvelines, France) was amplified by PCR using primers 5’GGCGCCTCTAGATCATAATCAGCCATA3’ and 5’GGCGCCCTTAAGATACATTGATGAGTT3’ before subcloning into the pGEMTeasy vector (Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France). After EcoRI digestion, the SV40 polyA fragment was purified with the NucleoSpin Extract II kit (Machery-Nagel, Hoerdt, France) and then subcloned into the EcoRI site of the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. Site directed mutagenesis was used to introduce a BsiWI site (5’ phosphorylated AGCGCAGGGAGCGGCGGCCGTACGATGCGCGGCAGCGGCACG3’) before the initiation codon and a MluI site (5’ phosphorylated 1 CCCGGGCCTGAGCCCTAAACGCGTGCCAGCCTCTGCCCTTGG3’) after the stop codon in the full length cDNA coding for the mouse LMα1 in the pCIS vector (kindly provided by P. -

Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B Activin a Receptor, Type IB

Table S1. Kinase clones included in human kinase cDNA library for yeast two-hybrid screening Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B activin A receptor, type IB ADCK2 aarF domain containing kinase 2 ADCK4 aarF domain containing kinase 4 AGK multiple substrate lipid kinase;MULK AK1 adenylate kinase 1 AK3 adenylate kinase 3 like 1 AK3L1 adenylate kinase 3 ALDH18A1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 18 family, member A1;ALDH18A1 ALK anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Ki-1) ALPK1 alpha-kinase 1 ALPK2 alpha-kinase 2 AMHR2 anti-Mullerian hormone receptor, type II ARAF v-raf murine sarcoma 3611 viral oncogene homolog 1 ARSG arylsulfatase G;ARSG AURKB aurora kinase B AURKC aurora kinase C BCKDK branched chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase BMPR1A bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type IA BMPR2 bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type II (serine/threonine kinase) BRAF v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 BRD3 bromodomain containing 3 BRD4 bromodomain containing 4 BTK Bruton agammaglobulinemia tyrosine kinase BUB1 BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog (yeast) BUB1B BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog beta (yeast) C9orf98 chromosome 9 open reading frame 98;C9orf98 CABC1 chaperone, ABC1 activity of bc1 complex like (S. pombe) CALM1 calmodulin 1 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM2 calmodulin 2 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM3 calmodulin 3 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CAMK1 calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I CAMK2A calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM kinase) II alpha CAMK2B calcium/calmodulin-dependent -

Overexpression of the Histone Dimethyltransferase G9a in Nucleus Accumbens Shell Increases Cocaine Self- Administration, Stress-Induced Reinstatement, and Anxiety

The Journal of Neuroscience, January 24, 2018 • 38(4):803–813 • 803 Neurobiology of Disease Overexpression of the Histone Dimethyltransferase G9a in Nucleus Accumbens Shell Increases Cocaine Self- Administration, Stress-Induced Reinstatement, and Anxiety X Ethan M. Anderson,1 Erin B. Larson,1 XDaniel Guzman,1 Anne Marie Wissman,1 Rachael L. Neve,2 XEric J. Nestler,3 and X David W. Self1 1Department of Psychiatry, The Seay Center for Basic and Applied Research in Psychiatric Illness, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, 75390, 2Viral Gene Transfer Core, Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, McGovern Institute for Brain Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, and 3Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Department of Neuroscience, New York, New York 10029 Repeated exposure to cocaine induces lasting epigenetic changes in neurons that promote the development and persistence of addiction. One epigenetic alteration involves reductions in levels of the histone dimethyltransferase G9a in nucleus accumbens (NAc) after chronic cocaine administration. This reduction in G9a may enhance cocaine reward because overexpressing G9a in the NAc decreases cocaine- conditioned place preference. Therefore, we hypothesized that HSV-mediated G9a overexpression in the NAc shell (NAcSh) would attenuate cocaine self-administration (SA) and cocaine-seeking behavior. Instead, we found that G9a overexpression, and the resulting increase in histone 3 lysine 9 dimethylation (H3K9me2), increases sensitivity to cocaine reinforcement and enhances motivation for cocaine in self-administering male rats. Moreover, when G9a overexpression is limited to the initial 15 d of cocaine SA training, it produces an enduring postexpression enhancement in cocaine SA and prolonged (over 5 weeks) increases in reinstatement of cocaine seeking induced by foot-shock stress, but in the absence of continued global elevations in H3K9me2. -

Chr21 Protein-Protein Interactions: Enrichment in Products Involved in Intellectual Disabilities, Autism and Late Onset Alzheimer Disease

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.11.872606; this version posted December 12, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Chr21 protein-protein interactions: enrichment in products involved in intellectual disabilities, autism and Late Onset Alzheimer Disease Julia Viard1,2*, Yann Loe-Mie1*, Rachel Daudin1, Malik Khelfaoui1, Christine Plancon2, Anne Boland2, Francisco Tejedor3, Richard L. Huganir4, Eunjoon Kim5, Makoto Kinoshita6, Guofa Liu7, Volker Haucke8, Thomas Moncion9, Eugene Yu10, Valérie Hindie9, Henri Bléhaut11, Clotilde Mircher12, Yann Herault13,14,15,16,17, Jean-François Deleuze2, Jean- Christophe Rain9, Michel Simonneau1, 18, 19, 20** and Aude-Marie Lepagnol- Bestel1** 1 Centre Psychiatrie & Neurosciences, INSERM U894, 75014 Paris, France 2 Laboratoire de génomique fonctionnelle, CNG, CEA, Evry 3 Instituto de Neurociencias CSIC-UMH, Universidad Miguel Hernandez-Campus de San Juan 03550 San Juan (Alicante), Spain 4 Department of Neuroscience, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21205 USA 5 Center for Synaptic Brain Dysfunctions, Institute for Basic Science, Daejeon 34141, Republic of Korea 6 Department of Molecular Biology, Division of Biological Science, Nagoya University Graduate School of Science, Furo, Chikusa, Nagoya, Japan 7 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Toledo, Toledo, OH, 43606, USA 8 Leibniz Forschungsinstitut für Molekulare Pharmakologie -

Neural Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Revert HFD-Dependent Memory Impairment Via CREB-BDNF Signalling

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Neural Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Revert HFD-Dependent Memory Impairment via CREB-BDNF Signalling Matteo Spinelli 1, Francesca Natale 1,2, Marco Rinaudo 1, Lucia Leone 1,2, Daniele Mezzogori 1, Salvatore Fusco 1,2,* and Claudio Grassi 1,2 1 Department of Neuroscience, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, 00168 Rome, Italy; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (F.N.); [email protected] (M.R.); [email protected] (L.L.); [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (C.G.) 2 Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, 00168 Rome, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 6 October 2020; Accepted: 25 November 2020; Published: 26 November 2020 Abstract: Overnutrition and metabolic disorders impair cognitive functions through molecular mechanisms still poorly understood. In mice fed with a high fat diet (HFD) we analysed the expression of synaptic plasticity-related genes and the activation of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB)-brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)-tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB) signalling. We found that a HFD inhibited both CREB phosphorylation and the expression of a set of CREB target genes in the hippocampus. The intranasal administration of neural stem cell (NSC)-derived exosomes (exo-NSC) epigenetically restored the transcription of Bdnf, nNOS, Sirt1, Egr3, and RelA genes by inducing the recruitment of CREB on their regulatory sequences. Finally, exo-NSC administration rescued both BDNF signalling and memory in HFD mice. Collectively, our findings highlight novel mechanisms underlying HFD-related memory impairment and provide evidence of the potential therapeutic effect of exo-NSC against metabolic disease-related cognitive decline. -

Whole Exome Sequencing in ADHD Trios from Single and Multi-Incident Families Implicates New Candidate Genes and Highlights Polygenic Transmission

European Journal of Human Genetics (2020) 28:1098–1110 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-020-0619-7 ARTICLE Whole exome sequencing in ADHD trios from single and multi-incident families implicates new candidate genes and highlights polygenic transmission 1,2 1 1,2 1,3 1 Bashayer R. Al-Mubarak ● Aisha Omar ● Batoul Baz ● Basma Al-Abdulaziz ● Amna I. Magrashi ● 1,2 2 2,4 2,4,5 6 Eman Al-Yemni ● Amjad Jabaan ● Dorota Monies ● Mohamed Abouelhoda ● Dejene Abebe ● 7 1,2 Mohammad Ghaziuddin ● Nada A. Al-Tassan Received: 26 September 2019 / Revised: 26 February 2020 / Accepted: 10 March 2020 / Published online: 1 April 2020 © The Author(s) 2020. This article is published with open access Abstract Several types of genetic alterations occurring at numerous loci have been described in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). However, the role of rare single nucleotide variants (SNVs) remains under investigated. Here, we sought to identify rare SNVs with predicted deleterious effect that may contribute to ADHD risk. We chose to study ADHD families (including multi-incident) from a population with a high rate of consanguinity in which genetic risk factors tend to 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: accumulate and therefore increasing the chance of detecting risk alleles. We employed whole exome sequencing (WES) to interrogate the entire coding region of 16 trios with ADHD. We also performed enrichment analysis on our final list of genes to identify the overrepresented biological processes. A total of 32 rare variants with predicted damaging effect were identified in 31 genes. At least two variants were detected per proband, most of which were not exclusive to the affected individuals. -

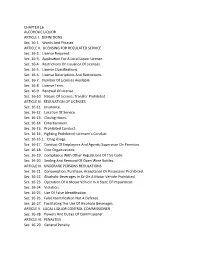

CHAPTER 16 ALCOHOLIC LIQUOR ARTICLE I. DEFINITIONS Sec. 16-1

CHAPTER 16 ALCOHOLIC LIQUOR ARTICLE I. DEFINITIONS Sec. 16-1. Words And Phrases. ARTICLE II. LICENSING FOR REGULATED SERVICE Sec. 16-2. License Required. Sec. 16-3. Application For A Local Liquor License. Sec. 16-4. Restrictions On Issuance Of Licenses. Sec. 16-5. License Classifications. Sec. 16-6. License Descriptions And Restrictions. Sec. 16-7. Number Of Licenses Available. Sec. 16-8. License Term. Sec. 16-9. Renewal Of License. Sec. 16-10. Nature Of License; Transfer Prohibited. ARTICLE III. REGULATION OF LICENSES Sec. 16-11. Insurance. Sec. 16-12. Location Of Service. Sec. 16-13. Closing Hours. Sec. 16-14. Entertainment. Sec. 16-15. Prohibited Conduct. Sec. 16-16. Fighting Prohibited; Licensee's Conduct. Sec. 16-16.1. Drug Usage. Sec. 16-17. Conduct Of Employees And Agents; Supervisor On Premises. Sec. 16-18. Civic Organizations. Sec. 16-19. Compliance With Other Regulations Of This Code. Sec. 16-20. Sealing And Removal Of Open Wine Bottles. ARTICLE IV. UNDERAGE PERSONS REGULATIONS Sec. 16-21. Consumption, Purchase, Acceptance Or Possession Prohibited. Sec. 16-22. Alcoholic Beverages In Or On A Motor Vehicle Prohibited. Sec. 16-23. Operation Of A Motor Vehicle In A State Of Impairment. Sec. 16-24. Violation. Sec. 16-25. Use Of False Identification. Sec. 16-26. False Identification Not A Defense. Sec. 16-27. Facilitating The Use Of Alcoholic Beverages. ARTICLE V. LOCAL LIQUOR CONTROL COMMISSIONER Sec. 16-28. Powers And Duties Of Commissioner. ARTICLE VI. PENALTIES Sec. 16-29. General Penalty. ARTICLE I DEFINITIONS Sec. 16-1. WORDS AND PHRASES. Unless the context otherwise requires, the following terms shall be construed according to the definitions set forth below: ACTING IN THE COURSE OF BUSINESS. -

Essential Genes and Their Role in Autism Spectrum Disorder

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Essential Genes And Their Role In Autism Spectrum Disorder Xiao Ji University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Bioinformatics Commons, and the Genetics Commons Recommended Citation Ji, Xiao, "Essential Genes And Their Role In Autism Spectrum Disorder" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2369. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2369 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2369 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Essential Genes And Their Role In Autism Spectrum Disorder Abstract Essential genes (EGs) play central roles in fundamental cellular processes and are required for the survival of an organism. EGs are enriched for human disease genes and are under strong purifying selection. This intolerance to deleterious mutations, commonly observed haploinsufficiency and the importance of EGs in pre- and postnatal development suggests a possible cumulative effect of deleterious variants in EGs on complex neurodevelopmental disorders. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a heterogeneous, highly heritable neurodevelopmental syndrome characterized by impaired social interaction, communication and repetitive behavior. More and more genetic evidence points to a polygenic model of ASD and it is estimated that hundreds of genes contribute to ASD. The central question addressed in this dissertation is whether genes with a strong effect on survival and fitness (i.e. EGs) play a specific oler in ASD risk. I compiled a comprehensive catalog of 3,915 mammalian EGs by combining human orthologs of lethal genes in knockout mice and genes responsible for cell-based essentiality. -

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Stratify Clinical Response to csDMARD-Therapy and Predict Radiographic Progression Frances Humby1,* Myles Lewis1,* Nandhini Ramamoorthi2, Jason Hackney3, Michael Barnes1, Michele Bombardieri1, Francesca Setiadi2, Stephen Kelly1, Fabiola Bene1, Maria di Cicco1, Sudeh Riahi1, Vidalba Rocher-Ros1, Nora Ng1, Ilias Lazorou1, Rebecca E. Hands1, Desiree van der Heijde4, Robert Landewé5, Annette van der Helm-van Mil4, Alberto Cauli6, Iain B. McInnes7, Christopher D. Buckley8, Ernest Choy9, Peter Taylor10, Michael J. Townsend2 & Costantino Pitzalis1 1Centre for Experimental Medicine and Rheumatology, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ, UK. Departments of 2Biomarker Discovery OMNI, 3Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, Genentech Research and Early Development, South San Francisco, California 94080 USA 4Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands 5Department of Clinical Immunology & Rheumatology, Amsterdam Rheumatology & Immunology Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 6Rheumatology Unit, Department of Medical Sciences, Policlinico of the University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy 7Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8TA, UK 8Rheumatology Research Group, Institute of Inflammation and Ageing (IIA), University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2WB, UK 9Institute of -

Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Hepatic Diseases

Review Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Hepatic Diseases: Therapeutic Possibilities of N-Acetylcysteine Kívia Queiroz de Andrade 1, Fabiana Andréa Moura 1,2, John Marques dos Santos 3, Orlando Roberto Pimentel de Araújo 3, Juliana Célia de Farias Santos 2 and Marília Oliveira Fonseca Goulart 3,* Received: 10 October 2015; Accepted: 4 December 2015; Published: 18 December 2015 Academic Editor: Guido Haenen 1 Pós Graduação em Ciências da Saúde (PPGCS), Campus A. C. Simões, Tabuleiro dos Martins, 57072-970 Maceió, AL, Brazil; [email protected] (K.Q.A.); [email protected] (F.A.M.) 2 Faculdade de Nutrição/Universidade Federal de Alagoas (FANUT/UFAL), Campus A. C. Simões, Tabuleiro dos Martins, 57072-970 Maceió, AL, Brazil; [email protected] 3 Instituto de Química e Biotecnologia (IQB), Universidade Federal de Alagoas (UFAL), Campus A. C. Simões, Tabuleiro dos Martins, 57072-970 Maceió, AL, Brazil; [email protected] (J.M.S.); [email protected] (O.R.P.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-82-98818-0463 Abstract: Liver disease is highly prevalent in the world. Oxidative stress (OS) and inflammation are the most important pathogenetic events in liver diseases, regardless the different etiology and natural course. N-acetyl-L-cysteine (the active form) (NAC) is being studied in diseases characterized by increased OS or decreased glutathione (GSH) level. NAC acts mainly on the supply of cysteine for GSH synthesis. The objective of this review is to examine experimental and clinical studies that evaluate the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory roles of NAC in attenuating markers of inflammation and OS in hepatic damage.