Beyond the Limit: the Dream of Sofya Kovalevskaya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 Volume 64, Number 7

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 Volume 64, Number 7 The Mathematics of Gravitational Waves: A Two-Part Feature page 684 The Travel Ban: Affected Mathematicians Tell Their Stories page 678 The Global Math Project: Uplifting Mathematics for All page 712 2015–2016 Doctoral Degrees Conferred page 727 Gravitational waves are produced by black holes spiraling inward (see page 674). American Mathematical Society LEARNING ® MEDIA MATHSCINET ONLINE RESOURCES MATHEMATICS WASHINGTON, DC CONFERENCES MATHEMATICAL INCLUSION REVIEWS STUDENTS MENTORING PROFESSION GRAD PUBLISHING STUDENTS OUTREACH TOOLS EMPLOYMENT MATH VISUALIZATIONS EXCLUSION TEACHING CAREERS MATH STEM ART REVIEWS MEETINGS FUNDING WORKSHOPS BOOKS EDUCATION MATH ADVOCACY NETWORKING DIVERSITY blogs.ams.org Notices of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 FEATURED 684684 718 26 678 Gravitational Waves The Graduate Student The Travel Ban: Affected Introduction Section Mathematicians Tell Their by Christina Sormani Karen E. Smith Interview Stories How the Green Light was Given for by Laure Flapan Gravitational Wave Research by Alexander Diaz-Lopez, Allyn by C. Denson Hill and Paweł Nurowski WHAT IS...a CR Submanifold? Jackson, and Stephen Kennedy by Phillip S. Harrington and Andrew Gravitational Waves and Their Raich Mathematics by Lydia Bieri, David Garfinkle, and Nicolás Yunes This season of the Perseid meteor shower August 12 and the third sighting in June make our cover feature on the discovery of gravitational waves -

Karl Weierstraß – Zum 200. Geburtstag „Alles Im Leben Kommt Doch Leider Zu Spät“ Reinhard Bölling Universität Potsdam, Institut Für Mathematik Prolog Nunmehr Im 74

1 Karl Weierstraß – zum 200. Geburtstag „Alles im Leben kommt doch leider zu spät“ Reinhard Bölling Universität Potsdam, Institut für Mathematik Prolog Nunmehr im 74. Lebensjahr stehend, scheint es sehr wahrscheinlich, dass dies mein einziger und letzter Beitrag über Karl Weierstraß für die Mediathek meiner ehemaligen Potsdamer Arbeitsstätte sein dürfte. Deshalb erlaube ich mir, einige persönliche Bemerkungen voranzustellen. Am 9. November 1989 ging die Nachricht von der Öffnung der Berliner Mauer um die Welt. Am Tag darauf schrieb mir mein Freund in Stockholm: „Herzlich willkommen!“ Ich besorgte das damals noch erforderliche Visum in der Botschaft Schwedens und fuhr im Januar 1990 nach Stockholm. Endlich konnte ich das Mittag- Leffler-Institut in Djursholm, im nördlichen Randgebiet Stockholms gelegen, besuchen. Dort befinden sich umfangreiche Teile des Nachlasses von Weierstraß und Kowalewskaja, die von Mittag-Leffler zusammengetragen worden waren. Ich hatte meine Arbeit am Briefwechsel zwischen Weierstraß und Kowalewskaja, die meine erste mathematikhistorische Publikation werden sollte, vom Inhalt her abgeschlossen. Das Manuskript lag in nahezu satzfertiger Form vor und sollte dem Verlag übergeben werden. Geradezu selbstverständlich wäre es für diese Arbeit gewesen, die Archivalien im Mittag-Leffler-Institut zu studieren. Aber auch als Mitarbeiter des Karl-Weierstraß- Institutes für Mathematik in Ostberlin gehörte ich nicht zu denen, die man ins westliche Ausland reisen ließ. – Nun konnte ich mir also endlich einen ersten Überblick über die Archivalien im Mittag-Leffler-Institut verschaffen. Ich studierte in jenen Tagen ohne Unterbrechung von morgens bis abends Schriftstücke, Dokumente usw. aus dem dortigen Archiv, denn mir stand nur eine Woche zur Verfügung. Am zweiten Tag in Djursholm entdeckte ich unter Papieren ganz anderen Inhalts einige lose Blätter, die Kowalewskaja beschrieben hatte. -

Halloweierstrass

Happy Hallo WEIERSTRASS Did you know that Weierestrass was born on Halloween? Neither did we… Dmitriy Bilyk will be speaking on Lacunary Fourier series: from Weierstrass to our days Monday, Oct 31 at 12:15pm in Vin 313 followed by Mesa Pizza in the first floor lounge Brought to you by the UMN AMS Student Chapter and born in Ostenfelde, Westphalia, Prussia. sent to University of Bonn to prepare for a government position { dropped out. studied mathematics at the M¨unsterAcademy. University of K¨onigsberg gave him an honorary doctor's degree March 31, 1854. 1856 a chair at Gewerbeinstitut (now TU Berlin) professor at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universit¨atBerlin (now Humboldt Universit¨at) died in Berlin of pneumonia often cited as the father of modern analysis Karl Theodor Wilhelm Weierstrass 31 October 1815 { 19 February 1897 born in Ostenfelde, Westphalia, Prussia. sent to University of Bonn to prepare for a government position { dropped out. studied mathematics at the M¨unsterAcademy. University of K¨onigsberg gave him an honorary doctor's degree March 31, 1854. 1856 a chair at Gewerbeinstitut (now TU Berlin) professor at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universit¨atBerlin (now Humboldt Universit¨at) died in Berlin of pneumonia often cited as the father of modern analysis Karl Theodor Wilhelm Weierstraß 31 October 1815 { 19 February 1897 born in Ostenfelde, Westphalia, Prussia. sent to University of Bonn to prepare for a government position { dropped out. studied mathematics at the M¨unsterAcademy. University of K¨onigsberg gave him an honorary doctor's degree March 31, 1854. 1856 a chair at Gewerbeinstitut (now TU Berlin) professor at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universit¨atBerlin (now Humboldt Universit¨at) died in Berlin of pneumonia often cited as the father of modern analysis Karl Theodor Wilhelm Weierstraß 31 October 1815 { 19 February 1897 sent to University of Bonn to prepare for a government position { dropped out. -

A Century of Mathematics in America, Peter Duren Et Ai., (Eds.), Vol

Garrett Birkhoff has had a lifelong connection with Harvard mathematics. He was an infant when his father, the famous mathematician G. D. Birkhoff, joined the Harvard faculty. He has had a long academic career at Harvard: A.B. in 1932, Society of Fellows in 1933-1936, and a faculty appointmentfrom 1936 until his retirement in 1981. His research has ranged widely through alge bra, lattice theory, hydrodynamics, differential equations, scientific computing, and history of mathematics. Among his many publications are books on lattice theory and hydrodynamics, and the pioneering textbook A Survey of Modern Algebra, written jointly with S. Mac Lane. He has served as president ofSIAM and is a member of the National Academy of Sciences. Mathematics at Harvard, 1836-1944 GARRETT BIRKHOFF O. OUTLINE As my contribution to the history of mathematics in America, I decided to write a connected account of mathematical activity at Harvard from 1836 (Harvard's bicentennial) to the present day. During that time, many mathe maticians at Harvard have tried to respond constructively to the challenges and opportunities confronting them in a rapidly changing world. This essay reviews what might be called the indigenous period, lasting through World War II, during which most members of the Harvard mathe matical faculty had also studied there. Indeed, as will be explained in §§ 1-3 below, mathematical activity at Harvard was dominated by Benjamin Peirce and his students in the first half of this period. Then, from 1890 until around 1920, while our country was becoming a great power economically, basic mathematical research of high quality, mostly in traditional areas of analysis and theoretical celestial mechanics, was carried on by several faculty members. -

The Figure of the Prostitute in Scandinavian Women's Literature

Scandinavica Vol 57 No 2 2018 The Figure of the Prostitute in Scandinavian Women’s Literature of The Modern Breakthrough Gisella Brouwer-Turci & Henk A. van der Liet University of Amsterdam Abstract Despite the fact that prostitution and the figure of the prostitute as represented in Scandinavian women’s literature of the last decades of the nineteenth-century is a significant topic, a systematic study on the role of prostitution in Scandinavian women’s literature of The Modern Breakthrough is largely lacking. This article, in which prostitution is conceptualised in the broadest meaning of the word, analyses the literary representations of the figure of the prostitute in the novel Lucie (1888) written by the Dano-Norwegian Amalie Skram, Rikka Gan (1904) by the Norwegian Ragnhild Jølsen, and the Swedish novella Aurore Bunge (1883) by Anne Charlotte Leffler. By means of close textual analysis, this article analyses how prostitution is represented in these three works and explores what factors were at play in causing the protagonist to be ‘fallen’ and with what consequences. The findings highlight the psychological and social implications of three unique forms of prostitution: prostitution within the marriage, a socially constructed form of prostitution as a shadow hanging over a marriage, and a relational form of prostitution parallel to a marriage. Keywords Modern Breakthrough, Scandinavian literature, women’s writing, prostitution, sexual transactions, Anne Charlotte Leffler, Amalie Skram, Ragnhild Jølsen 36 Scandinavica Vol 57 No 2 2018 Introduction Prostitution was a central theme in Scandinavian society and culture during the last decades of the nineteenth century and the first years of the twentieth century. -

Fundamental Theorems in Mathematics

SOME FUNDAMENTAL THEOREMS IN MATHEMATICS OLIVER KNILL Abstract. An expository hitchhikers guide to some theorems in mathematics. Criteria for the current list of 243 theorems are whether the result can be formulated elegantly, whether it is beautiful or useful and whether it could serve as a guide [6] without leading to panic. The order is not a ranking but ordered along a time-line when things were writ- ten down. Since [556] stated “a mathematical theorem only becomes beautiful if presented as a crown jewel within a context" we try sometimes to give some context. Of course, any such list of theorems is a matter of personal preferences, taste and limitations. The num- ber of theorems is arbitrary, the initial obvious goal was 42 but that number got eventually surpassed as it is hard to stop, once started. As a compensation, there are 42 “tweetable" theorems with included proofs. More comments on the choice of the theorems is included in an epilogue. For literature on general mathematics, see [193, 189, 29, 235, 254, 619, 412, 138], for history [217, 625, 376, 73, 46, 208, 379, 365, 690, 113, 618, 79, 259, 341], for popular, beautiful or elegant things [12, 529, 201, 182, 17, 672, 673, 44, 204, 190, 245, 446, 616, 303, 201, 2, 127, 146, 128, 502, 261, 172]. For comprehensive overviews in large parts of math- ematics, [74, 165, 166, 51, 593] or predictions on developments [47]. For reflections about mathematics in general [145, 455, 45, 306, 439, 99, 561]. Encyclopedic source examples are [188, 705, 670, 102, 192, 152, 221, 191, 111, 635]. -

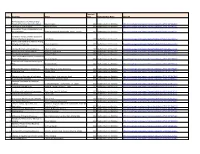

List of Mathematics, Statistics E Books

Copyright Sr No Book Title Author Year English Package Name OpenURL An Introduction to the Mathematical 1 Theory of the Navier-Stokes Equations Giovanni Galdi 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-09620-9 2 The Proof is in the Pudding Steven G. Krantz 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-48744-1 Inequalities: Theory of Majorization and 3 Its Applications Albert W. Marshall, Ingram Olkin, Barry C. Arnold 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-68276-1 Functional Analysis, Sobolev Spaces and 4 Partial Differential Equations Haim Brezis 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-70914-7 Neutral and Indifference Portfolio Pricing, 5 Hedging and Investing Srdjan Stojanovic 2012 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-71418-9 6 The Real Numbers and Real Analysis Ethan D. Bloch 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-72177-4 7 An Introduction to Hopf Algebras Robert G. Underwood 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-72766-0 8 It's a Nonlinear World Richard H. Enns 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-75340-9 The Colorado Mathematical Olympiad and 9 Further Explorations Alexander Soifer 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-75472-7 -

Remembering Sofia Kovalevskaya

Remembering Sofia Kovalevskaya Michèle Audin Remembering Sofia Kovalevskaya Michèle Audin Institut de recherche mathématique avancée Université de Strasbourg et CNRS 7 rue René-Descartes 67084 Strasbourg Cedex France [email protected] Whilst we have made considerable efforts to contact all holders of copyright material contained in this book. We have failed to locate some of them. Should holders wish to contact the Publisher, we will make every effort to come to some arrangement with them ISBN 978-0-85729-928-4 e-ISBN 978-0-85729-929-1 DOI 10.1007/978-0-85729-929-1 Springer London Dordrecht Heidelberg New York British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2011935730 Mathematics Subject Classification: 01-00, 01455, 14H70, 70Hxx, 70Exx, 35A10 Translation from the French language edition: ‘Souvenirs sur Sofia Kovalevskaya’ by Michèle Audin Copyright © 2008 Calvage et Mounet, France http://www.calvage-et-mounet.fr/ All Rights Reserved Springer-Verlag London Limited 2011 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copy- right, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licenses issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. The use of registered names, trademarks, etc., in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Inauguration

INAUGURATION OF THE PERMANENT SECRETARIAT OF THE INTERNATIONAL MATHEMATICAL UNION February 1, 2011, Berlin, Germany Ribbon Cutting Ceremony: Professor Dr. Martin Grötschel, Dr. Georg Schütte, Professor Dr. Ingrid Daubechies, Dr. Knut Nevermann, Professor Dr. Jürgen Sprekels (from left to right), and Gauss on the wall. Contents The IMU and Berlin ..................................................................................................................... 3 Where to find the IMU Secretariat ............................................................................................... 4 Adresses delivered at the Opening Ceremony ............................................................................. 5 Dr. Georg Schütte, State Secretary at the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research .............................. 5 Professor Dr. Jürgen Zöllner, Senator for Education, Science and Research of the State of Berlin, speech read by Dr. Knut Nevermann, State Secretary for Science and Research at the Berlin Senate .................................................... 8 Professor Dr. Ingrid Daubechies, President of the International Mathematical Union ............. 10 Professor Dr. Christian Bär, President of the German Mathematical Society (DMV) ............. 12 Professor Dr. Jürgen Sprekels, Director of the Weierstrass Institute, Berlin ............................ 13 The Team of the Permanent Secretariat ..................................................................................... 16 Impressions from the Opening -

The Book and Printed Culture of Mathematics in England and Canada, 1830-1930

Paper Index of the Mind: The Book and Printed Culture of Mathematics in England and Canada, 1830-1930 by Sylvia M. Nickerson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto © Copyright by Sylvia M. Nickerson 2014 Paper Index of the Mind: The Book and Printed Culture of Mathematics in England and Canada, 1830-1930 Sylvia M. Nickerson Doctor of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto 2014 Abstract This thesis demonstrates how the book industry shaped knowledge formation by mediating the selection, expression, marketing, distribution and commercialization of mathematical knowledge. It examines how the medium of print and the practices of book production affected the development of mathematical culture in England and Canada during the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Chapter one introduces the field of book history, and discusses how questions and methods arising from this inquiry might be applied to the history of mathematics. Chapter two looks at how nineteenth century printing technologies were used to reproduce mathematics. Mathematical expressions were more difficult and expensive to produce using moveable type than other forms of content; engraved diagrams required close collaboration between author, publisher and engraver. Chapter three examines how editorial decision-making differed at book publishers compared to mathematical journals and general science journals. Each medium followed different editorial processes and applied distinct criteria in decision-making about what to publish. ii Daniel MacAlister, Macmillan and Company’s reader of science, reviewed mathematical manuscripts submitted to the company and influenced which ones would be published as books. -

Reception of Foreign Women Writers in the Slovenian Literary System of the Long 19Th Century

Edited by Reception of Foreign Katja Mihurko Poniž Women Writers in the Slovenian Literary System of the Long 19th Century HERA 07 A4.indd 1 15.5.2017 12:09:30 HERA 07 A4.indd 2 15.5.2017 12:09:30 Reception of Foreign Women Writers in the Slovenian Literary System of the Long 19th Century Edited by Katja Mihurko Poniž HERA 07 A4.indd 3 15.5.2017 12:09:30 Reception of Foreign Women Writers in the Slovenian Literary System of the Long 19th Century Edited by: Katja Mihurko Poniž Expert Reviewers: Barbara Simoniti, Peter Scherber English Translation: Melita Silič: Introduction, From Passing References to Inspiring Writers the Presence of Foreign Women Writers in the Press, Libraries, Theatre Performances and in the Works of Slovenian Authors; Leonora Flis: Ambiguous Views on Femininity in the Writings of Two “New Women” in the Fin de sieclè Zofka Kveder’s Inspirational Encounters with Laura Marholm’s Modern women. English Language Editing: Leonora Flis: Visualization of the WomenWriters Database: Interdisciplinary Collaboration Experiments 2012—2015). Designed by: Kontrastika Published by: University of Nova Gorica Press, P.O. Box 301, Vipavska 13, SI-5001 Nova Gorica Acrobat Reader, ePUB http://www.ung.si/sl/zalozba/ http://www.ung.si/en/publisher/ 27.3.2017 Publication year: 2017 University of Nova Gorica Press The book was financially supported by the HERA Joint Research Programme (www.heranet.info), co-funded by AHRC, AKA, BMBF via PT-DLR, DASTI, ETAG, FCT, FNR, FNRS, FWF, FWO, HAZU, IRC, LMT, MHEST, NWO, NCN, RANNÍS, RCN, VR and The European Community FP7 2007. -

Karl Weierstrass' Bicentenary

Karl Weierstrass’ Bicentenary G.I. Sinkevich Saint Petersburg State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering Vtoraja Krasnoarmejskaja ul. 4, St. Petersburg, 190005, Russia [email protected] Abstract. Academic biography of Karl Weierstrass, his basic works, influence of his doctrine on the development of mathematics. Key words: Karl Weierstrass, academic biography. In 2015, the mathematical world celebrates the bicentenary of the great German mathematician Karl Weierstrass (1815-1897) who created the modern mathematical analysis. Childhood and adolescence. Karl Theodor Wilhelm Weierstrass was born on 31 October 1815 in Ostenfelde (Westphalia) to a catholic family of burgomaster’s secretary, Wilhelm Weierstrass and Theodora born Vonderforst. Karl was the eldest child. He was 12 when his mother died. His father’s service was associated with the Tax Department, and therefore, the family had to move from one place to another quite often. His father was a genteel person. He taught his children French and English. Karl started attending school in Münster, and at the age of 14, he entered the catholic Gymnasium at Theodorianum in Padeborn. In addition to good general education, he obtained a good mathematical training at the Gymnasium: stereometry, trigonometry, Diophantine analysis, series expansion. The schooling was thorough. It was for good reason that when the Franco-Prussian War was over, Bismarck said that the war was won by the schoolteacher. There was a scientific library in the Gymnasium. Weierstrass was known to browse mathematical magazines there, especially Crelle’s Journal (Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik). Each issue of the Journal incorporated four fascicles. In certain years, even two issues were published.