A Russian Childhood Sofya Kovalevskaya a Russian Childhood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 Volume 64, Number 7

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 Volume 64, Number 7 The Mathematics of Gravitational Waves: A Two-Part Feature page 684 The Travel Ban: Affected Mathematicians Tell Their Stories page 678 The Global Math Project: Uplifting Mathematics for All page 712 2015–2016 Doctoral Degrees Conferred page 727 Gravitational waves are produced by black holes spiraling inward (see page 674). American Mathematical Society LEARNING ® MEDIA MATHSCINET ONLINE RESOURCES MATHEMATICS WASHINGTON, DC CONFERENCES MATHEMATICAL INCLUSION REVIEWS STUDENTS MENTORING PROFESSION GRAD PUBLISHING STUDENTS OUTREACH TOOLS EMPLOYMENT MATH VISUALIZATIONS EXCLUSION TEACHING CAREERS MATH STEM ART REVIEWS MEETINGS FUNDING WORKSHOPS BOOKS EDUCATION MATH ADVOCACY NETWORKING DIVERSITY blogs.ams.org Notices of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 FEATURED 684684 718 26 678 Gravitational Waves The Graduate Student The Travel Ban: Affected Introduction Section Mathematicians Tell Their by Christina Sormani Karen E. Smith Interview Stories How the Green Light was Given for by Laure Flapan Gravitational Wave Research by Alexander Diaz-Lopez, Allyn by C. Denson Hill and Paweł Nurowski WHAT IS...a CR Submanifold? Jackson, and Stephen Kennedy by Phillip S. Harrington and Andrew Gravitational Waves and Their Raich Mathematics by Lydia Bieri, David Garfinkle, and Nicolás Yunes This season of the Perseid meteor shower August 12 and the third sighting in June make our cover feature on the discovery of gravitational waves -

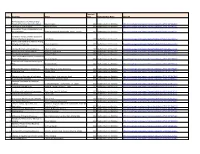

List of Mathematics, Statistics E Books

Copyright Sr No Book Title Author Year English Package Name OpenURL An Introduction to the Mathematical 1 Theory of the Navier-Stokes Equations Giovanni Galdi 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-09620-9 2 The Proof is in the Pudding Steven G. Krantz 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-48744-1 Inequalities: Theory of Majorization and 3 Its Applications Albert W. Marshall, Ingram Olkin, Barry C. Arnold 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-68276-1 Functional Analysis, Sobolev Spaces and 4 Partial Differential Equations Haim Brezis 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-70914-7 Neutral and Indifference Portfolio Pricing, 5 Hedging and Investing Srdjan Stojanovic 2012 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-71418-9 6 The Real Numbers and Real Analysis Ethan D. Bloch 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-72177-4 7 An Introduction to Hopf Algebras Robert G. Underwood 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-72766-0 8 It's a Nonlinear World Richard H. Enns 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-75340-9 The Colorado Mathematical Olympiad and 9 Further Explorations Alexander Soifer 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-75472-7 -

Remembering Sofia Kovalevskaya

Remembering Sofia Kovalevskaya Michèle Audin Remembering Sofia Kovalevskaya Michèle Audin Institut de recherche mathématique avancée Université de Strasbourg et CNRS 7 rue René-Descartes 67084 Strasbourg Cedex France [email protected] Whilst we have made considerable efforts to contact all holders of copyright material contained in this book. We have failed to locate some of them. Should holders wish to contact the Publisher, we will make every effort to come to some arrangement with them ISBN 978-0-85729-928-4 e-ISBN 978-0-85729-929-1 DOI 10.1007/978-0-85729-929-1 Springer London Dordrecht Heidelberg New York British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2011935730 Mathematics Subject Classification: 01-00, 01455, 14H70, 70Hxx, 70Exx, 35A10 Translation from the French language edition: ‘Souvenirs sur Sofia Kovalevskaya’ by Michèle Audin Copyright © 2008 Calvage et Mounet, France http://www.calvage-et-mounet.fr/ All Rights Reserved Springer-Verlag London Limited 2011 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copy- right, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licenses issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. The use of registered names, trademarks, etc., in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Arxiv:Hep-Th/0212169V1 15 Dec 2002

LPT–Orsay–02–111 RUB–TP2–17/02 hep-th/0212169 Noncompact Heisenberg spin magnets from high-energy QCD III. Quasiclassical approach ´ 1 2 3 S.E. Derkachov , G.P. Korchemsky and A.N. Manashov ∗ 1 Department of Mathematics, St.-Petersburg Technology Institute, 198013 St.-Petersburg, Russia 2 Laboratoire de Physique Th´eorique†, Universit´ede Paris XI, 91405 Orsay C´edex, France 3 Institut f¨ur Theoretische Physik II, Ruhr–Universit¨at Bochum, 44780 Bochum, Germany Abstract: The exact solution of the noncompact SL(2, C) Heisenberg spin magnet reveals a hidden sym- metry of the energy spectrum. To understand its origin, we solve the spectral problem for arXiv:hep-th/0212169v1 15 Dec 2002 the model within quasiclassical approach. In this approach, the integrals of motion satisfy the Bohr-Sommerfeld quantization conditions imposed on the orbits of classical motion. In the rep- resentation of the separated coordinates, the latter wrap around a Riemann surface defined by the spectral curve of the model. A novel feature of the obtained quantization conditions is that they involve both the α and β periods of the action differential on the Riemann surface, thus allowing us to find their− solutions− by exploring the full modular group of the spectral curve. We demonstrate that the quasiclassical energy spectrum is in a good agreement with the exact results. ∗ Permanent address: Department of Theoretical Physics, Sankt-Petersburg State University, 199034 St.- Petersburg, Russia †Unite Mixte de Recherche du CNRS (UMR 8627) Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Noncompact Heisenberg spin magnet 6 2.1. Classicalmodel .................................... 6 2.2. -

Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 11-2013 Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry Marcelline Hutton [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Slavic Languages and Societies Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hutton, Marcelline, "Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry" (2013). Zea E-Books. 21. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/21 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry N Marcelline Hutton Many Russian women of the late 19th and early 20th centuries tried to find happy marriages, authentic religious life, liberal education, and ful- filling work as artists, doctors, teachers, and political activists. Some very remarkable ones found these things in varying degrees, while oth- ers sought unsuccessfully but no less desperately to transcend the genera- tions-old restrictions imposed by church, state, village, class, and gender. Like a Slavic “Downton Abbey,” this book tells the stories, not just of their outward lives, but of their hearts and minds, their voices and dreams, their amazing accomplishments against overwhelming odds, and their roles as feminists and avant-gardists in shaping modern Russia and, in- deed, the twentieth century in the West. -

S. Kovalevsky: a Mathematical Lesson Author(S): Karen D

S. Kovalevsky: A Mathematical Lesson Author(s): Karen D. Rappaport Reviewed work(s): Source: The American Mathematical Monthly, Vol. 88, No. 8 (Oct., 1981), pp. 564-574 Published by: Mathematical Association of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2320506 . Accessed: 25/02/2013 16:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Mathematical Association of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Mathematical Monthly. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded on Mon, 25 Feb 2013 16:08:52 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions S. KOVALEVSKY: A MATHEMATICAL LESSON KAREN D. RAPPAPORT MathemcaticsDepartmenit, Essex CounitvCollege, Newark, NJ 07102 SofyaKovalevsky was a notedwriter whose works include both fiction and nonfiction.She was also a politicalactivist and a public advocate of feminism.In addition,she was a brilliant mathematicianwho made significant contributions despite the enormous educational and political obstaclesthat she had to overcome.Somehow her manyachievements have been forgotten.In thosefew instances where her work has not been lostit has been denigratedby such studiesas FelixKlein's history of nineteenth-centurymathematics. Klein dismisses Kovalevsky's work in the followingmanner: "Her worksare done in thestyle of Weierstrassand so one doesn'tknow how muchof herown ideas are in them."'He findssomething wrong with all herresearch and credits her withonly one positiveaccomplishment, drawing Weierstrass out of his shell throughtheir correspondence.It is timeto set thisrecord straight and to let thefacts speak for themselves. -

Solutions to Nonlinear Evolutionary Parabolic Equations of the Diffusion Wave Type

S S symmetry Article Solutions to Nonlinear Evolutionary Parabolic Equations of the Diffusion Wave Type Alexander Kazakov Matrosov Institute for System Dynamics and Control Theory of Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, 664033 Irkutsk, Russia; [email protected] Abstract: The article deals with nonlinear second-order evolutionary partial differential equations (PDEs) of the parabolic type with a reasonably general form. We consider the case of PDE degenera- tion when the unknown function vanishes. Similar equations in various forms arise in continuum mechanics to describe some diffusion and filtration processes as well as to model heat propagation in the case when the properties of the process depend significantly on the unknown function (concen- tration, temperature, etc.). One of the exciting and meaningful classes of solutions to these equations is diffusion (heat) waves, which describe the propagation of perturbations over a stationary (zero) background with a finite velocity. It is known that such effects are atypical for parabolic equations; they arise as a consequence of the degeneration mentioned above. We prove the existence theorem of piecewise analytical solutions of the considered type and construct exact solutions (ansatz). Their search reduces to the integration of Cauchy problems for second-order ODEs with a singularity in the term multiplying the highest derivative. In some special cases, the construction is brought to explicit formulas that allow us to study the properties of solutions. The case of the generalized porous medium equation turns out to be especially interesting as the constructed solution has the form of a soliton moving at a constant velocity. Keywords: nonlinear parabolic equation; porous medium equation; diffusion wave; existence Citation: Kazakov, A. -

Part 1: Summary of Evidence That Integration Is Professionally Useful and Effective

1 1. A Review of Studies Demonstrating the Effectiveness of Integrating Arts, Music, Performing, Crafts and Design into Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics and Medical Education, Part 1: Summary of Evidence that Integration Is Professionally Useful and Effective. Robert Root-Bernstein*, Department of Physiology, 567 Wilson Road, Room 2201, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824 USA; [email protected] Ania Pathak, Michigan State University Neuroscience Graduate Program, Giltner Hall, 293 Farm Lane Room 108, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824; and Michigan State University College of Osteopathic Medicine, East Fee Hall, 965 Fee Road; Room A136, East Lansing, MI 4882 USA; [email protected] Michele Root-Bernstein, 720 Gainsborough Drive, East Lansing, MI 48823 USA: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed Abstract: This is Part 1 of a three part analysis of studies concerning useful ways in which visual and plastic arts, music, performing, crafts, and design (referred to for simplicity as Arts- Crafts-Design or ACD) may improve learning of Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics and Medicine (STEMM) and increase professional success in these subjects. We address: 1) what are the ways in which arts and STEM can interact fruitfully; 2) which of these have been explored using well-devised studies and what do these tell us about efficacy; 3) where are the gaps (and therefore the opportunities) that can readily be addressed by new studies; and 4) what kinds of methods can be used to generate reliable data? Part 1 summarizes studies demonstrating that ACD are valuable to STEMM professionals, providing a taxonomy of twelve fundamental ways that STEMM professionals employ ACD ranging from shared mental “tools”, creative processes, and aesthetic considerations, to the discovery of novel problems and phenomena, analogies, materials, principles, methods and even mental recreation. -

Mathematical Monuments in Finland

Bridges 2021 Conference Proceedings Mathematical Monuments in Finland Osmo Pekonen1, Kristóf Fenyvesi2, and Johan Stén3 1University of Jyväskylä, Finland; [email protected] 2University of Jyväskylä, Finland; [email protected] 3University of Helsinki, Finland; [email protected] Abstract With “mathematical monuments” we mean either monuments for famous mathematicians and their achievements or works of art representing mathematical objects in public places. We present a panoply of such monuments in Finland for the purposes of the mathematical tourist visiting our country. As we are interested in symbolic representations of science, we take a broad view of the notion of “monument” and take into account also some minor artefacts, such as portraits, medals and stamps, and other semiotic signs, such as street names and commemorative plates, illustrating some highlights of the history of mathematics in Finland. Introduction Some great centres of science in the world have so many monuments for past scientists and their deeds that it has been worthwhile to publish specialized guides for visitors who wish to spot them. The Hungarian couple of science historians István and Magdolna Hargittai have recently published such guidebooks about their home city Budapest [1] but also about New York [2], Moscow [3], and London [4]. Unsurprisingly, there is a similar guidebook about Paris [5]. The German couple of mathematicians Martin and Iris Grötschel have produced an analogous book focusing on mathematical sights in Berlin [6]. The Mathematical Intelligencer has a column entitled “The Mathematical Tourist” devoted to spotting of mathematical monuments. Finland holds an honourable place in the history of mathematics as a country. -

Notices of the American Mathematical Society

ISSN 0002·9920 NEW! Version 5 Sharing Your Work Just Got Easier • Typeset PDF in the only software that allows you to transform U\TEX files to PDF fully hyperlinked and with embedded graphics in over 50 formats • Export documents as RTF with editable mathematics (Microsoft Word and MathType compatible) • Share documents on the web as HTML with mathematics as MathML or graphics The Gold Standard for Mathematical Publishing <J (.\t ) :::: Scientific WorkPlace and Scientific Word make writing, sharing, and doing . ach is to aPPlY theN mathematics easier. A click of a button of Stanton s ap\)1 o : esti1nates of the allows you to typeset your documents in to constrnct nonparametnc IHEX. And, with Scientific WorkPlace, . f· ddff2i) and ref: diff1} ~r-l ( xa _ .x~ ) K te . 1 . t+l you can compute and plot solutions with 1 t~ the integrated computer algebra engine, f!(:;) == 6. "T-lK(L,....t=l h MuPAD® 2.5. rr-: MilcKichan SOFTWARE , INC. Tools for Scientific Creativity since 1981 Editors INTERNATIONAL Morris Weisfeld Managing Editor Dan Abramovich MATHEMATICS Enrico Arbarello Joseph Bernstein Enrico Bombieri RESEARCH PAPERS Richard E. Borcherds Alexei Borodin Jean Bourgain Marc Burger Website: http://imrp.hindawi.com Tobias. Golding Corrado DeConcini IMRP provides very fast publication of lengthy research articles of high current interest in Percy Deift all areas of mathematics. All articles are fully refereed and are judged by their contribution Robbert Dijkgraaf to the advancement of the state of the science of mathematics. Issues are published as fre S. K. Donaldson quently as necessary. Each issue will contain only one article. -

The Legacy of James Clerk Maxwell and Herrmann Von Helmholtz Peter Skiff Bard College

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Faculty Books & Manuscripts Bard Faculty Publications 2016 The hP ysicist - Philosophers: The Legacy of James Clerk Maxwell and Herrmann von Helmholtz Peter Skiff Bard College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.bard.edu/facbooks Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Philosophy of Science Commons, and the Physics Commons Recommended Citation Skiff, Peter, "The hP ysicist - Philosophers: The Legacy of James Clerk Maxwell and Herrmann von Helmholtz" (2016). Faculty Books & Manuscripts. 1. http://digitalcommons.bard.edu/facbooks/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Bard Faculty Publications at Bard Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Books & Manuscripts by an authorized administrator of Bard Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PHYSICIST - PHILOSOPHERS The Legacy of James Clerk Maxwell and Herrmann von Helmholtz Peter Skiff Bard College, 2016 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work was begun 25 years into a 50 year career at Bard College. This position gave me access to an extraordinary range of exceptional faculty, distinguished visiting scholars, and brilliant student researchers, all of whom inspired and informed im investigating academic fields I pursued: mathematical physics and the history and philosophy of science. In addition the editors of the American Library Association’s Choice magazine provided literally hundreds of books for review for college libraries. It is from this trove of ideas and information I have been assembling this book. I am particularly grateful to particular advice and information from Hannah Arendt, Heinrich Bluecher, Irma Brandeis, and A. -

Women in Mathematics: Historical and Modern Perspectives

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Report No. 2/2017 DOI: 10.4171/OWR/2017/2 Mini-Workshop: Women in Mathematics: Historical and Modern Perspectives Organised by Tinne Hoff Kjeldsen, Copenhagen Nicola Oswald, Wuppertal Renate Tobies, Jena 8 January – 14 January 2017 Abstract. The aim of the workshop is to build a bridge between research on the situation of women in mathematics at the beginning of coeducative studies and the current circumstances in academia. The issue of women in mathematics has been a recent political and social hot topic in the mathe- matical community. As thematic foci we place a double comparison: besides shedding light on differences and similarities in several European countries, we complete this investigation by comparing the developments of women studies from the beginnings. This shall lead to new results on tradition and suggest improvements on the present situation. Mathematics Subject Classification (2010): 01A55, 01A60, 01A70, 01A80. Introduction by the Organisers The aim of the workshop was to build a bridge between research on the situation of women in mathematics at the beginning of coeducative studies and the current circumstances in academia. The issue of women in mathematics has been a recent political and social hot topic in the mathematical community. “The taking into account of relevant gender and diversity aspects is an essential part of qualitatively excellent research.” 1 1 ”Die Ber¨ucksichtigung von relevanten Gender- und Diversity-Aspekten ist ein wesentliches Element qualitativ hochwertiger Forschung.” aus: Forschungsorientierte Gleichstellungs- standards der DFG (2008), http://www.dfg.de/download/pdf/foerderung/grundlagen\_dfg\ _foerderung/chancengleichheit\\/forschungsorientierte\_gleichstellungsstandards.pdf 84 Oberwolfach Report 2/2017 Besides the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), also the European Union implemented equality goals into their research support program Horizon 2020.