The Emerging Women of the Russian Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 Volume 64, Number 7

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 Volume 64, Number 7 The Mathematics of Gravitational Waves: A Two-Part Feature page 684 The Travel Ban: Affected Mathematicians Tell Their Stories page 678 The Global Math Project: Uplifting Mathematics for All page 712 2015–2016 Doctoral Degrees Conferred page 727 Gravitational waves are produced by black holes spiraling inward (see page 674). American Mathematical Society LEARNING ® MEDIA MATHSCINET ONLINE RESOURCES MATHEMATICS WASHINGTON, DC CONFERENCES MATHEMATICAL INCLUSION REVIEWS STUDENTS MENTORING PROFESSION GRAD PUBLISHING STUDENTS OUTREACH TOOLS EMPLOYMENT MATH VISUALIZATIONS EXCLUSION TEACHING CAREERS MATH STEM ART REVIEWS MEETINGS FUNDING WORKSHOPS BOOKS EDUCATION MATH ADVOCACY NETWORKING DIVERSITY blogs.ams.org Notices of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 FEATURED 684684 718 26 678 Gravitational Waves The Graduate Student The Travel Ban: Affected Introduction Section Mathematicians Tell Their by Christina Sormani Karen E. Smith Interview Stories How the Green Light was Given for by Laure Flapan Gravitational Wave Research by Alexander Diaz-Lopez, Allyn by C. Denson Hill and Paweł Nurowski WHAT IS...a CR Submanifold? Jackson, and Stephen Kennedy by Phillip S. Harrington and Andrew Gravitational Waves and Their Raich Mathematics by Lydia Bieri, David Garfinkle, and Nicolás Yunes This season of the Perseid meteor shower August 12 and the third sighting in June make our cover feature on the discovery of gravitational waves -

Lenin and the Bourgeois Press

REQUEST TO READERS Progress Publishers would be glad to have your opinion of this book, its translation and design and any suggestions you may have for future publications. Please send your comments to 17, Zubovsky Boulevard, Moscow, U.S,S.R. Boris Baluyev AND TBE BOURGEOIS PRESS Progress Publishers Moscow Translated from the Russian by James Riordan Designed by Yuri Davydov 6opac 6aJiyee JIEHMH IlOJIEMl1311PYET C 6YJ>)l(YA3HO'A IlPECCO'A Ha Qlj2J1UUCKOM 11301Ke © IlOJIHTH3L(aT, 1977 English translation © Progress Publishers 1983 Printed in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics 0102020000-346 _ E 32 83 014(01)-83 Contents Introduction . 5 "Highly Interesting-from the Negative Aspect" 8 "Capitalism and the Press" . 23 "For Lack of a Clean Principled Weapon They Snatch at a Dirty One" . 53 "I Would Rather Let Myself Be Drawn and Quartered... " 71 "A Socialist Paper Must Carry on Polemics" 84 "But What Do These Facts Mean?" . 98 "All Praise to You, Writers for Rech and Duma!" 106 "Our Strength Lies in Stating the Truth!" 120 "The Despicable Kind of Trick People Who Have Been Ordered to Raise a Cheer Would Use" . 141 "The Innumerable Vassal Organs of Russian Liberalism" 161 "This Appeared Not in Novoye Vremya, but in a Paper That Calls Itself a Workers' Newspaper" . 184 ··one Chorus. One Orchestra·· 201 INTRODUCTION The polemical writings of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin continue to set an unsurpassed standard of excellence for journalists and all representatives of the progressive press. They teach ideo logical consistency and develop the ability to link political issues of the moment to Marxist philosophical theory. -

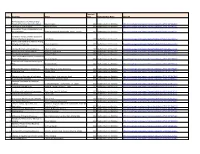

List of Mathematics, Statistics E Books

Copyright Sr No Book Title Author Year English Package Name OpenURL An Introduction to the Mathematical 1 Theory of the Navier-Stokes Equations Giovanni Galdi 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-09620-9 2 The Proof is in the Pudding Steven G. Krantz 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-48744-1 Inequalities: Theory of Majorization and 3 Its Applications Albert W. Marshall, Ingram Olkin, Barry C. Arnold 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-68276-1 Functional Analysis, Sobolev Spaces and 4 Partial Differential Equations Haim Brezis 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-70914-7 Neutral and Indifference Portfolio Pricing, 5 Hedging and Investing Srdjan Stojanovic 2012 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-71418-9 6 The Real Numbers and Real Analysis Ethan D. Bloch 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-72177-4 7 An Introduction to Hopf Algebras Robert G. Underwood 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-72766-0 8 It's a Nonlinear World Richard H. Enns 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-75340-9 The Colorado Mathematical Olympiad and 9 Further Explorations Alexander Soifer 2011 Mathematics and Statistics http://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-0-387-75472-7 -

Communist Manifesto”

IN THE VANGUARD OF REVOLUTIONARY ACTION: THE FIRST RUSSIAN EDITIONS OF THE “COMMUNIST MANIFESTO” 1. The story behind the first Russian translation of the “Communist Manifesto” is rather enigmatic. It was published without indicating not only the authors or the editor and the printer, but also without a title page, publication date or place of publication. The publication of it was quite a surprise to Marx, who wrote to Engels (29.04.1870): Finally, ONE COPY of the Russian translation of our Communist Manifesto for you. I saw in the Werker, etc., that the Kolokol Publishing House, which was willed to Bakunin, also includes ‘this stuff’, so ordered 6 copies from Geneva. It's very interesting for us.1 The information about this edition appeared also in Marx and Engels’ preface to the second edition, where they claim that it was translated by Bakunin and published early in the “’sixties by the printing office of the Kolokol”2. Nevertheless, this information is questionable. One must remember that Marx and Engels were not exactly precise with such details. It is a well-known fact that Engels, for example, wrongly attributed the 1882 translation to Vera Zasulich and not Plekhanov in the preface to the German edition in 1890. We know for sure that the text was printed in Geneva by Ludwig Czerniecki. This can be verified not only because the paper and fonts match those from “Kolokol” of 15 February 18693; it is also confirmed in the correspondence between the printer and Nikolai Ogarev. It was published by Volnaya Russkaya Tipographiya4, probably in September 1869. -

Remembering Sofia Kovalevskaya

Remembering Sofia Kovalevskaya Michèle Audin Remembering Sofia Kovalevskaya Michèle Audin Institut de recherche mathématique avancée Université de Strasbourg et CNRS 7 rue René-Descartes 67084 Strasbourg Cedex France [email protected] Whilst we have made considerable efforts to contact all holders of copyright material contained in this book. We have failed to locate some of them. Should holders wish to contact the Publisher, we will make every effort to come to some arrangement with them ISBN 978-0-85729-928-4 e-ISBN 978-0-85729-929-1 DOI 10.1007/978-0-85729-929-1 Springer London Dordrecht Heidelberg New York British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2011935730 Mathematics Subject Classification: 01-00, 01455, 14H70, 70Hxx, 70Exx, 35A10 Translation from the French language edition: ‘Souvenirs sur Sofia Kovalevskaya’ by Michèle Audin Copyright © 2008 Calvage et Mounet, France http://www.calvage-et-mounet.fr/ All Rights Reserved Springer-Verlag London Limited 2011 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copy- right, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licenses issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. The use of registered names, trademarks, etc., in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://eprints.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Lenin and the Iskra Faction of the RSDLP 1899-1903 Richard Mullin Doctor of Philosophy Resubmission University of Sussex March 2010 1 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree ……………………………….. 2 Contents Contents.......................................................................................................................3 Acknowledgements……………..…………………………………………………...4 Abstract........................................................................................................................5 Notes on Names, Texts and Dates…….....……………………..…………………...6 Chapter One: Historical and Historiographical Context…………………..…....7 i) 1899-1903 in the Context of Russian Social-Democratic History and Theory …12 ii) Historiographical Trends in the Study of Lenin and the RSDLP …………...…..23 iii) How the thesis develops -

Introduction 11. I Have Approached This Subject in Greater Detail in J. D

NOTES Introduction 11. I have approached this subject in greater detail in J. D. White, Karl Marx and the Intellectual Origins of Dialectical Materialism (Basingstoke and London, 1996). 12. V. I. Lenin, Collected Works, Vol. 38, p. 180. 13. K. Marx, Grundrisse, translated by M. Nicolaus (Harmondsworth, 1973), p. 408. 14. N. I. Ziber, Teoriia tsennosti i kapitala D. Rikardo v sviazi s pozdneishimi dopolneniiami i raz"iasneniiami. Opyt kritiko-ekonomicheskogo issledovaniia (Kiev, 1871). 15. N. G. Chernyshevskii, ‘Dopolnenie i primechaniia na pervuiu knigu politicheskoi ekonomii Dzhon Stiuarta Millia’, Sochineniia N. Chernyshevskogo, Vol. 3 (Geneva, 1869); ‘Ocherki iz politicheskoi ekonomii (po Milliu)’, Sochineniia N. Chernyshevskogo, Vol. 4 (Geneva, 1870). Reprinted in N. G. Chernyshevskii, Polnoe sobranie sochineniy, Vol. IX (Moscow, 1949). 16. Arkhiv K. Marksa i F. Engel'sa, Vols XI–XVI. 17. M. M. Kovalevskii, Obshchinnoe zemlevladenie, prichiny, khod i posledstviia ego razlozheniia (Moscow, 1879). 18. Marx to the editorial board of Otechestvennye zapiski, November 1877, in Karl Marx Frederick Engels Collected Works, Vol. 24, pp. 196–201. 19. Marx to Zasulich, 8 March 1881, in Karl Marx Frederick Engels Collected Works, Vol. 24, pp. 346–73. 10. It was published in the journal Vestnik Narodnoi Voli, no. 5 (1886). 11. D. Riazanov, ‘V Zasulich i K. Marks’, Arkhiv K. Marksa i F. Engel'sa, Vol. 1 (1924), pp. 269–86. 12. N. F. Daniel'son, ‘Ocherki nashego poreformennogo obshch- estvennogo khoziaistva’, Slovo, no. 10 (October 1880), pp. 77–143. 13. N. F. Daniel'son, Ocherki nashego poreformennogo obshchestvennogo khozi- aistva (St Petersburg, 1893). 14. V. V. Vorontsov, Sud'by kapitalizma v Rossii (St Petersburg, 1882). -

A Russian Childhood Sofya Kovalevskaya a Russian Childhood

A Russian Childhood Sofya Kovalevskaya A Russian Childhood TRANSLATED, EDITED AND INTRODUCED BY BEATRICE STILLMAN With an Analysis of Kovalevskaya' s Mathematics by P. Y. Kochina USSR Academy of Sciences Springer Science+Business Media New York This book has been selected for inclusion in the Sources and Translation Series of the Russian Institute, Columbia University. AMS'classification 01A70 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Kovalevskafa, Sof; Vasil'evna Korvin-Krukovskafa, 1850-1891. A Russian childhood. Translation of Vospominanifa detstva. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Kovalevskai';, Sofi; Vasil'evna Korvin-Krukovskai-;, 1850- 1891. 2. Mathematicians-Russia-Biography. I. Title. QA29.K67A3513 510'.92'4 [B] 78-12955 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be translated or reproduced in any form without written permission from Springer-Verlag. © 1978 by Beatrice Stillman Originally published by Springer-Verlag New York in 197R. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1978 ISBN 978-1-4419-2808-5 ISBN 978-1-4757-3839-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4757-3839-1 For Pelageya Y akovlevna Kochina, untiring scholar and generous spirit, in admiration and friendship Contents Pre/ace tX Introduction 1 CHAPTER ONE Earliest Memories 47 CHAPTER TWO The Thief 59 CHAPTER THREE Metamorphosis 77 CHAPTER FOUR Palibino 82 CHAPTER FIVE Mzss Smith 98 vii Contents CHAPTER SIX Uncle Pyotr V asil£evich Krukovsky 111 CHAPTER SEVEN Uncle Fyodor Fyodorovich Shubert 124 CHAPTER EIGHT My Sister 133 CHAPTER NINE Anyuta's Nihilism 145 CHAPTER TEN Anyuta's First Literary Experiments 155 CHAPTER ELEVEN Our Friendship with Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky 173 Notes 201 An Autobiographical Sketch 213 On the Scientific Work of Sofya Kovalevskaya, by P. -

Sofia Kovalevskaya

Sofia Kovalevskaya Claire Larkin Kovalevskaya's life Sofia Kovalevskaya was born in Moscow, Russia on January 15th, 1850. She was born into a wealthy, well- educated family with an older sister and a younger brother. Sofia was often seen as the neglected middle child because both of her siblings were well-mannered and well-admired; she was always the odd one out. For these reasons, Sofia was not a happy child. She also had a governess who tried to make her into a young lady. However, Sofia always wanted to do math and science, subjects that were not acceptable for young women to do during that time period. One reason for her acquiring her interest in mathematics was her uncle, Pyotr Vasilievich Krukovsky, who spoke about the subject often in front of her. When she was 11, she grew a deep interest for the subject. She would study it on the wall of her nursery and then began studying it with a tutor. However, her father did not like the idea of his daughter doing math, so he put a stop to all of it. This forced her to learn math in the shadows of her family. Sofia was also extremely lucky that she lived next to Professor Tyrtov, a well known professor of mathematics and physics as well as author of a physics book Sofia read while she was young. Professor Tyrtov was beyond dumbfounded when he found out that Sofia had read and understood his book. He even claims that she understood and explained it in the same fashion that the founders of trigonometry did. -

Arxiv:Hep-Th/0212169V1 15 Dec 2002

LPT–Orsay–02–111 RUB–TP2–17/02 hep-th/0212169 Noncompact Heisenberg spin magnets from high-energy QCD III. Quasiclassical approach ´ 1 2 3 S.E. Derkachov , G.P. Korchemsky and A.N. Manashov ∗ 1 Department of Mathematics, St.-Petersburg Technology Institute, 198013 St.-Petersburg, Russia 2 Laboratoire de Physique Th´eorique†, Universit´ede Paris XI, 91405 Orsay C´edex, France 3 Institut f¨ur Theoretische Physik II, Ruhr–Universit¨at Bochum, 44780 Bochum, Germany Abstract: The exact solution of the noncompact SL(2, C) Heisenberg spin magnet reveals a hidden sym- metry of the energy spectrum. To understand its origin, we solve the spectral problem for arXiv:hep-th/0212169v1 15 Dec 2002 the model within quasiclassical approach. In this approach, the integrals of motion satisfy the Bohr-Sommerfeld quantization conditions imposed on the orbits of classical motion. In the rep- resentation of the separated coordinates, the latter wrap around a Riemann surface defined by the spectral curve of the model. A novel feature of the obtained quantization conditions is that they involve both the α and β periods of the action differential on the Riemann surface, thus allowing us to find their− solutions− by exploring the full modular group of the spectral curve. We demonstrate that the quasiclassical energy spectrum is in a good agreement with the exact results. ∗ Permanent address: Department of Theoretical Physics, Sankt-Petersburg State University, 199034 St.- Petersburg, Russia †Unite Mixte de Recherche du CNRS (UMR 8627) Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Noncompact Heisenberg spin magnet 6 2.1. Classicalmodel .................................... 6 2.2. -

THE RISE and FALL of the BLACK HUNDRED by Jacob Langer Department of History Duke Univers

CORRUPTION AND THE COUNTERREVOLUTION: THE RISE AND FALL OF THE BLACK HUNDRED by Jacob Langer Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Marty Miller, Supervisor ___________________________ Donald Raleigh ___________________________ Warren Lerner ___________________________ Alex Roland Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2007 ABSTRACT CORRUPTION AND THE COUNTERREVOLUTION: THE RISE AND FALL OF THE BLACK HUNDRED by Jacob Langer Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Marty Miller, Supervisor ___________________________ Donald Raleigh ___________________________ Warren Lerner ___________________________ Alex Roland An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2007 Copyright by Jacob Langer 2007 Abstract This dissertation analyzes the ideology and activities of the Black Hundred movement at the end of the Imperial period in Russia (1905-1917). It seeks to explain the reasons for the sudden, rapid expansion of Black Hundred organizations in 1905, as well as the causes of their decline, which began just two years after their appearance. It further attempts to elucidate the complex relationship between the Black Hundred and Russian authorities, including the central government and local officials. The problem is approached by offering two distinct perspectives on the Black Hundred. First, a broad overview of the movement is presented. The focus here is on the headquarter branches of Black Hundred organizations in St. Petersburg, but these chapters also look at the activities of many different provincial branches, relating trends in the provinces to events in the center in order to draw conclusions about the nature of the overall movement. -

Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 11-2013 Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry Marcelline Hutton [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Slavic Languages and Societies Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hutton, Marcelline, "Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry" (2013). Zea E-Books. 21. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/21 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry N Marcelline Hutton Many Russian women of the late 19th and early 20th centuries tried to find happy marriages, authentic religious life, liberal education, and ful- filling work as artists, doctors, teachers, and political activists. Some very remarkable ones found these things in varying degrees, while oth- ers sought unsuccessfully but no less desperately to transcend the genera- tions-old restrictions imposed by church, state, village, class, and gender. Like a Slavic “Downton Abbey,” this book tells the stories, not just of their outward lives, but of their hearts and minds, their voices and dreams, their amazing accomplishments against overwhelming odds, and their roles as feminists and avant-gardists in shaping modern Russia and, in- deed, the twentieth century in the West.