Leon Trotsky and World War One: August 1914-March 1917

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Bolsheviki: the Beginnings of the First Red Scare, 1917 to 1918

Steeplechase: An ORCA Student Journal Volume 3 Issue 2 Article 4 2019 American Bolsheviki: The Beginnings of the First Red Scare, 1917 to 1918 Jonathan Dunning Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/steeplechase Part of the European History Commons, Other History Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Dunning, Jonathan (2019) "American Bolsheviki: The Beginnings of the First Red Scare, 1917 to 1918," Steeplechase: An ORCA Student Journal: Vol. 3 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/steeplechase/vol3/iss2/4 This Feature is brought to you for free and open access by the The Office of Research and Creative Activity at Murray State's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Steeplechase: An ORCA Student Journal by an authorized editor of Murray State's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. American Bolsheviki: The Beginnings of the First Red Scare, 1917 to 1918 Abstract A consensus has developed among historians that widespread panic consumed the American public and government as many came to fear a Bolshevik coup of the United States government and the undermining of the American way of life beginning in early 1919. Known as the First Red Scare, this period became one of the most well-known episodes of American fear of Communism in US history. With this focus on the events of 1919 to 1920, however, historians of the First Red Scare have often ignored the initial American reaction to the October Revolution in late 1917 and throughout 1918. -

Great Britain. Foreign Office. Wellington House Publications

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c86m3dcm No online items Inventory of the Great Britain. Foreign Office. Wellington House publications Finding aid prepared by Trevor Wood Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2008, 2014 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory of the Great Britain. XX230 1 Foreign Office. Wellington House publications Title: Great Britain. Foreign Office. Wellington House publications Date (inclusive): 1914-1918 Collection Number: XX230 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 13 manuscript boxes, 5 card file boxes, 1 cubic foot box(6.2 Linear Feet) Abstract: Books, pamphlets, and miscellany, relating to World War I and British participation in it. Card file drawers at the Hoover Institution Library & Archives describe this collection. Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Great Britain. Foreign Office. Wellington House publications, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Historical Note Propaganda section of the British Foreign Office. Scope and Content of Collection Books, pamphlets, and miscellany, relating to World War I and British participation in it. Subjects and Indexing Terms World War, 1914-1918 -- Propaganda Propaganda, British World War, 1914-1918 -- Great Britain box 1 "The Achievements of the Zeppelins." By a Swede. -

Revolution in Real Time: the Russian Provisional Government, 1917

ODUMUNC 2020 Crisis Brief Revolution in Real Time: The Russian Provisional Government, 1917 ODU Model United Nations Society Introduction seventy-four years later. The legacy of the Russian Revolution continues to be keenly felt The Russian Revolution began on 8 March 1917 to this day. with a series of public protests in Petrograd, then the Winter Capital of Russia. These protests But could it have gone differently? Historians lasted for eight days and eventually resulted in emphasize the contingency of events. Although the collapse of the Russian monarchy, the rule of history often seems inventible afterwards, it Tsar Nicholas II. The number of killed and always was anything but certain. Changes in injured in clashes with the police and policy choices, in the outcome of events, government troops in the initial uprising in different players and different accidents, lead to Petrograd is estimated around 1,300 people. surprising outcomes. Something like the Russian Revolution was extremely likely in 1917—the The collapse of the Romanov dynasty ushered a Romanov Dynasty was unable to cope with the tumultuous and violent series of events, enormous stresses facing the country—but the culminating in the Bolshevik Party’s seizure of revolution itself could have ended very control in November 1917 and creation of the differently. Soviet Union. The revolution saw some of the most dramatic and dangerous political events the Major questions surround the Provisional world has ever known. It would affect much Government that struggled to manage the chaos more than Russia and the ethnic republics Russia after the Tsar’s abdication. -

666 Slavic Review

666 Slavic Review STRUVE: LIBERAL ON THE LEFT, 1870-1905. By Richard Pipes. Russian Research Center Studies, 64. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970. xiii, 415 pp. $10.00. Few figures in Russian intellectual history present more tantalizing problems to a biographer than Peter Struve. In the 1890s he was the best-known domestic pro tagonist of Marxism; early in the new century he played a seminal role in the movement for constitutional democracy; and after the 1905 revolution he became a leading advocate of Russian state interest. Contemporaries, not surprisingly, wondered how anyone, least of all a man of unquestioned integrity, could reconcile such contradictory beliefs. On the far left he was distrusted by many as a renegade, and Lenin in particular developed for his former colleague a personal antipathy that left a lasting imprint upon the Bolshevik political credo. Richard Pipes's magisterial study is the first work in any language to give this brilliant and paradoxical character his due. We are given a convincing portrait of a man smitten by "intellectual schizophrenia," beholden only to the dictates of his conscience: "his mind worked so quickly, and on so many different levels, that even his most devoted admirers could never tell where he stood on any particular issue"; yet he possessed such penetrating insight into the problems of his age that he was usually a leap ahead of everyone else. Ordinary mortals, alas, do not take kindly to such paragons, and even today his personality will probably command more respect than affection. Struve was a remarkably reticent man, by the standards of the old Russian intelligentsia, and for several key periods of his life the information available is regrettably sparse. -

Leon Trotsky Three Concepts of the Russian Revolution 1

Leon Trotsky Three Concepts of the Russian Revolution 1 The Revolution of 1905 came to be not only the “general rehearsal” of 1917 but also the laboratory in which all the fundamental groupings of Russian political life were worked out and all the tendencies and shadings inside Russian Marxism were projected. At the core of the arguments and divergences was, needless to say, the question concerning the historical nature of the Russian Revolution and its future course of development. That conflict of concepts and prognoses has no direct bearing on the biography of Stalin, who did not participate in it in his own right. The few propagandist articles he wrote on that subject are utterly devoid of theoretical interest. Scores of Bolsheviks who plied the pen popularised the same thoughts, and did it considerably better. Any critical exposition of Bolshevism’s revolutionary concepts naturally belongs in a biography of Lenin. But theories have their own fate. Although during the period of the First Revolution [1905] and subsequently, as late as 1923, at the time when the revolutionary doctrines were elaborated and applied, Stalin had no independent position whatever, a sudden change occurred in 1924, which opened an epoch of bureaucratic reaction and radical transvaluation of the past. The film of the revolution was unwound in reverse order. Old doctrines were subjected either to a new evaluation or a new interpretation. Thus, rather unexpectedly at first glance, attention was focused on the concept of “permanent revolution” as the prime source of all the fallacies of “Trotskyism”. For many years to come criticism of that concept formed the main content of all the theoretical – sit venio verbo – writings of Stalin and his collaborators. -

409 the Men Named Lennon and Lenin – Great Britain’S “Imagine There’S No Heaven” Lennon and the Soviet Union’S “Imagine There’S No Heaven” Lenin

#409 The Men Named Lennon and Lenin – Great Britain’s “Imagine there’s no heaven” Lennon and the Soviet Union’s “Imagine there’s no heaven” Lenin Now we turn to The Men Named Lennon and Lenin, still as a part of the umbrella theme of The Second Oswald Head Wounds, which is related to The Deadly Wound of the Beast, Phase II. The Lord’s ordainment of the two men named Lennon and Lenin, with the spirit of “Imagine there’s no heaven” being a central theme in each of their lives, is tied to “the man clothed in linen” in Daniel 12:6-7. Daniel 12:4-6 (KJV) But thou, O Daniel, shut up the words, and seal the book, even to THE TIME OF THE END: many shall run to and fro, and knowledge shall be increased. 5 Then I Daniel looked, and, behold, there stood other two, the one on this side of the bank of the river, and the other on that side of the bank of the river. 6 And one said to THE MAN CLOTHED IN LINEN, which was upon the waters of the river, How long shall it be to the end of these wonders? “The man clothed in linen” will need to be elaborated upon at another time. Nonetheless, we can start to set up “the man clothed in linen” by understanding how it ties to what we are currently studying – the Second Oswald Head Wound defeat of the Soviet Union, which occurs at “the time of the end.” Key Understanding: The men named Lennon and Lenin. -

Chapter 23: War and Revolution, 1914-1919

The Twentieth- Century Crisis 1914–1945 The eriod in Perspective The period between 1914 and 1945 was one of the most destructive in the history of humankind. As many as 60 million people died as a result of World Wars I and II, the global conflicts that began and ended this era. As World War I was followed by revolutions, the Great Depression, totalitarian regimes, and the horrors of World War II, it appeared to many that European civilization had become a nightmare. By 1945, the era of European domination over world affairs had been severely shaken. With the decline of Western power, a new era of world history was about to begin. Primary Sources Library See pages 998–999 for primary source readings to accompany Unit 5. ᮡ Gate, Dachau Memorial Use The World History Primary Source Document Library CD-ROM to find additional primary sources about The Twentieth-Century Crisis. ᮣ Former Russian pris- oners of war honor the American troops who freed them. 710 “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.” —Winston Churchill International ➊ ➋ Peacekeeping Until the 1900s, with the exception of the Seven Years’ War, never ➌ in history had there been a conflict that literally spanned the globe. The twentieth century witnessed two world wars and numerous regional conflicts. As the scope of war grew, so did international commitment to collective security, where a group of nations join together to promote peace and protect human life. 1914–1918 1919 1939–1945 World War I League of Nations World War II is fought created to prevent wars is fought ➊ Europe The League of Nations At the end of World War I, the victorious nations set up a “general associa- tion of nations” called the League of Nations, which would settle interna- tional disputes and avoid war. -

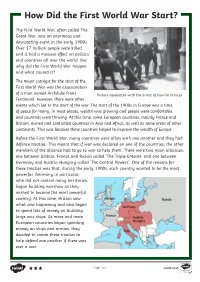

How Did the First World War Start?

How Did the First World War Start? The First World War, often called The Great War, was an enormous and devastating event in the early 1900s. Over 17 million people were killed and it had a massive effect on politics and countries all over the world. But why did the First World War happen and what caused it? The major catalyst for the start of the First World War was the assassination of a man named Archduke Franz Picture associated with the arrest of Gavrilo Princip Ferdinand. However, there were other events which led to the start of the war. The start of the 1900s in Europe was a time of peace for many. In most places, wealth was growing and people were comfortable and countries were thriving. At this time, some European countries, mainly France and Britain, owned and controlled countries in Asia and Africa, as well as some areas of other continents. This was because these countries helped to improve the wealth of Europe. Before the First World War, many countries were allies with one another and they had defence treaties. This meant that if war was declared on one of the countries, the other members of the alliance had to go to war to help them. There were two main alliances, one between Britain, France and Russia called ‘The Triple Entente’ and one between Germany and Austria-Hungary called ‘The Central Powers’. One of the reasons for these treaties was that, during the early 1900s, each country wanted to be the most powerful. Germany in particular, who did not control many territories, began building warships as they wished to become the most powerful country. -

Lenin and the Bourgeois Press

REQUEST TO READERS Progress Publishers would be glad to have your opinion of this book, its translation and design and any suggestions you may have for future publications. Please send your comments to 17, Zubovsky Boulevard, Moscow, U.S,S.R. Boris Baluyev AND TBE BOURGEOIS PRESS Progress Publishers Moscow Translated from the Russian by James Riordan Designed by Yuri Davydov 6opac 6aJiyee JIEHMH IlOJIEMl1311PYET C 6YJ>)l(YA3HO'A IlPECCO'A Ha Qlj2J1UUCKOM 11301Ke © IlOJIHTH3L(aT, 1977 English translation © Progress Publishers 1983 Printed in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics 0102020000-346 _ E 32 83 014(01)-83 Contents Introduction . 5 "Highly Interesting-from the Negative Aspect" 8 "Capitalism and the Press" . 23 "For Lack of a Clean Principled Weapon They Snatch at a Dirty One" . 53 "I Would Rather Let Myself Be Drawn and Quartered... " 71 "A Socialist Paper Must Carry on Polemics" 84 "But What Do These Facts Mean?" . 98 "All Praise to You, Writers for Rech and Duma!" 106 "Our Strength Lies in Stating the Truth!" 120 "The Despicable Kind of Trick People Who Have Been Ordered to Raise a Cheer Would Use" . 141 "The Innumerable Vassal Organs of Russian Liberalism" 161 "This Appeared Not in Novoye Vremya, but in a Paper That Calls Itself a Workers' Newspaper" . 184 ··one Chorus. One Orchestra·· 201 INTRODUCTION The polemical writings of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin continue to set an unsurpassed standard of excellence for journalists and all representatives of the progressive press. They teach ideo logical consistency and develop the ability to link political issues of the moment to Marxist philosophical theory. -

THE FIRST PRAVDA and the RUSSIAN MARXIST TRADITION by JAMES D

THE FIRST PRAVDA AND THE RUSSIAN MARXIST TRADITION By JAMES D. WHITE I THE appearance of the first Pravdal is an episode of the Bolshevik party's history which has never received any systematic treatment either by Western or Soviet scholars. It is an aspect of the I905 revolution which the party historians and memoirists have been for the most part very eager to forget, and since Western investigators have apparently been unaware of its existence they have allowed its consignment to oblivion to take place without comment. That this first Pravda to be connected with the Bolshevik party is not widely known is hardly surprising, because in this case the exclusion from the historical record took place long before the Bolshevik party came to power. For, following the 1905 revolution, Pravda's editor, A. A. Bogdanov, was subjected to the kind of campaign of silence which was a foretaste of those later applied to Trotsky and Stalin. Nevertheless, the journal Pravda and the group of intellectuals associated with it occupy an important place in the history of Bolshevism. Indeed, it is true to say that without reference to this periodical Russian intellectual history would be incomplete and the evolution of Russian Marxism imperfectly understood. Although Pravda would certainly merit a more extended study both as a source and as a historical event in itself, the present paper is limited to a description of the circumstances which attended the appearance of the journal, the group of people who surrounded it, and an attempt to place it in its ideological context. -

At Berne: Kurt Eisner, the Opposition and the Reconstruction of the International

ROBERT F. WHEELER THE FAILURE OF "TRUTH AND CLARITY" AT BERNE: KURT EISNER, THE OPPOSITION AND THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE INTERNATIONAL To better understand why Marxist Internationalism took on the forms that it did during the revolutionary epoch that followed World War I, it is useful to reconsider the "International Labor and Socialist Con- ference" that met at Berne from January 26 to February 10,1919. This gathering not only set its mark on the "reconstruction" of the Second International, it also influenced both the formation and the development of the Communist International. It is difficult, however, to comprehend fully what transpired at Berne unless the crucial role taken in the deliberations by Kurt Eisner, on the one hand, and the Zimmerwaldian Opposition, on the other, is recognized. To a much greater extent than has generally been realized, the immediate success and the ultimate failure of the Conference depended on the Bavarian Minister President and the loosely structured opposition group to his Left. Nevertheless every scholarly study of the Conference to date, including Arno Mayer's excellent treatment of the "Stillborn Berne Conference", tends to un- derestimate Eisner's impact while largely ignoring the very existence of the Zimmerwaldian Opposition.1 Yet, if these two elements are neglected it becomes extremely difficult, if not impossible, to fathom the real significance of Berne. Consequently there is a need to reevaluate 1 In Mayer's case this would seem to be related to two factors: first, the context in which he examines Berne, namely the attempt by Allied labor leaders to influence the Paris Peace Conference; and second, his reliance on English and French accounts of the Conference. -

Background Guide, and to Issac and Stasya for Being Great Friends During Our Weird Chicago Summer

Russian Duma 1917 (DUMA) MUNUC 33 ONLINE 1 Russian Duma 1917 (DUMA) | MUNUC 33 Online TABLE OF CONTENTS ______________________________________________________ CHAIR LETTERS………………………….….………………………….……..….3 ROOM MECHANICS…………………………………………………………… 6 STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM………………………….……………..…………......9 HISTORY OF THE PROBLEM………………………………………………………….16 ROSTER……………………………………………………….………………………..23 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………..…………….. 46 2 Russian Duma 1917 (DUMA) | MUNUC 33 Online CHAIR LETTERS ____________________________________________________ My Fellow Russians, We stand today on the edge of a great crisis. Our nation has never been more divided, more war- stricken, more fearful of the future. Yet, the promise and the greatness of Russia remains undaunted. The Russian Provisional Government can and will overcome these challenges and lead our Motherland into the dawn of a new day. Out of character. To introduce myself, I’m a fourth-year Economics and History double major, currently writing a BA thesis on World War II rationing in the United States. I compete on UChicago’s travel team and I additionally am a CD for our college conference. Besides that, I am the VP of the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity, previously a member of an all-men a cappella group and a proud procrastinator. This letter, for example, is about a month late. We decided to run this committee for a multitude of reasons, but I personally think that Russian in 1917 represents such a critical point in history. In an unlikely way, the most autocratic regime on Earth became replaced with a socialist state. The story of this dramatic shift in government and ideology represents, to me, one of the most interesting parts of history: that sometimes facts can be stranger than fiction.