Science Disinformation in a Time of Pandemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pandemic Data Sharing: How the Canadian Constitution Turned Into a Suicide Pact

Pandemic Data Sharing: How the Canadian Constitution Turned Into a Suicide Pact Amir Attaran & Adam R. Houston “The choice is not between order and liberty. It is between liberty with order and anarchy without either. There is danger that, if the court does not temper its doctrinaire logic with a little practical wisdom, it will convert the constitutional Bill of Rights into a suicide pact.” Justice Robert Jackson in Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949) * * * For decades, public health professionals, scholars, and on multiple occasions the Auditor General of Canada, have raised warnings about Canada’s dysfunctional system of public health data sharing. These warnings have been reiterated in the wake of repeated outbreaks – most prominently SARS in 2003, but also foodborne listeriosis in 2008, and H1N1 influenza in 2009. Every single time, the warnings have been clear that unless Canada better prepares itself for a pandemic, many thousands could die, as when the “Spanish Flu” killed an estimated 55,000 Canadians between 1918 and 1920. Almost exactly a century later, COVID-19 arrived. While SARS killed 44 people in Canada, currently (mid-May 2020) COVID-19 kills several fold that every day. Nor is satisfactory progress being made, for unlike some countries, including very seriously affected ones that promptly reversed the epidemic’s growth, in Canada there is still no reversal after approximately two months of lockdown. Why? There are countless reasons, but legally, the most fundamental problem is that epidemic responses are handicapped by a mythological, schismatic, self-destructive view of federalism, which endures despite being flagrantly wrong. -

Sars and Public Health in Ontario

THE SARS COMMISSION INTERIM REPORT SARS AND PUBLIC HEALTH IN ONTARIO The Honourable Mr. Justice Archie Campbell Commissioner April 15, 2004 INTERIM REPORT ♦ SARS AND PUBLIC HEALTH IN ONTARIO Table of Contents Table of Contents Dedication Letter of Transmittal EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................1 1. A Broken System .....................................................................................................................24 2. Reason for Interim Report .....................................................................................................25 3. Hindsight...................................................................................................................................26 4. What Went Right?....................................................................................................................28 5. A Constellation of Problems..................................................................................................30 Problem 1: The Decline of Public Health ...............................................................................32 Problem 2: Lack of Preparedness: The Pandemic Flu Example..........................................37 Problem 3: Lack of Transparency.............................................................................................47 Problem 4: Lack of Provincial Public Health Leadership .....................................................51 Problem 5: Lack of Perceived -

Monday, May 25

MONDAY, MAY 25 14:20 – 15:50 CONCURRENT SESSIONS PHPC Ebola in Canada: What have we learned from this outbreak that we didn’t know before? PLAZA C, SECOND FLOOR MSPC The Ebola virus disease outbreak(s) in West Africa have raised several issues for public health and health care, especially with respect to infection prevention and control in health and other settings. The issues have ranged from world travel policy to personal protective equipment protocols. As with many similar public health events in the past (e.g., SARS, H1N1 influenza), the scientific foundations, valid and relevant surveillance data, estimates of risk and burden, effectiveness of interventions, principles and ethics, priorities and goals should provide the basis for evidence-informed, wise and fair decisions. These decisions may result in reaffirmation or change of policies, programs and practice and often have many consequences, including levels of preparedness and response, resource allocation, protocol changes, and specific education and advice for health practitioners and others working and living in the settings of everyday life. These, in turn, can be expected to affect attitudes and behaviour in society. What have we learned (or should we learn) from this outbreak that we didn’t know (or should have known) before? To address these issues from a knowledge translation perspective, panel members will provide the stimuli for interactive responses from the audience and other members of the panel for what promises to be an engaging and educational event. Learning Objectives: Describe the scientific, practical, political and ethical considerations for policy and program decisions for a low-probability, high- consequence public health event in Canada. -

De.Sputniknews.Com

de.sputniknews.com The German-language site of Sputnik News, a Russian state-owned news agency that publishes propaganda and disinformation to serve Proceed with caution: This website severely violates basic the Kremlin’s interests. standards of credibility and transparency. Score: 12.5/100 Ownership and Sputnik Deutschland is a subsidiary of Rossiya Financing Segodnya, a Russian government-owned international Does not repeatedly publish news agency. Rossiya Segodnya was established in false content (22points) December 2013 by Russian President Vladimir Putin. Gathers and presents The international broadcasting service, Voice of Russia, information responsibly (18) and the state-run news agency, RIA Novosti, were Regularly corrects or clarifies dissolved and merged into Rossiya Segodnya. errors (12.5) Rossiya Segodnya launched Sputnik in November Handles the difference between news and opinion responsibly 2014. Sputnik Deutschland also runs the radio station (12.5) SNA-Radio, which broadcasts in collaboration with the Avoids deceptive headlines (10) Bavarian radio station Mega Radio. Website discloses ownership The site runs advertisements. and financing (7.5) Clearly labels advertising (7.5) Content Sputnik Deutschland covers international politics, Reveals who's in charge, business, science, technology, culture, and celebrities. including any possible conflicts It has a separate section for German news, which of interest (5) primarily covers politics and major crime stories. The site provides names of content creators, along with The site states on its About Us (Über Uns) page that it either contact or biographical “reports on global politics and business only for information (5) audiences abroad.” Sputnik is headquartered in Moscow, has bureaus in 34 countries, and produces Criteria are listed in order of content in 30 languages. -

In Their Own Words: Voices of Jihad

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as CHILD POLICY a public service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and PUBLIC SAFETY effective solutions that address the challenges facing SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY the public and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. in their own words Voices of Jihad compilation and commentary David Aaron Approved for public release; distribution unlimited C O R P O R A T I O N This book results from the RAND Corporation's continuing program of self-initiated research. -

Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 11 Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Transatlantic Security Studies, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Kathleen Bailey presents evidence of forgeries to the press corps. Credit: The Washington Times Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference By Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 11 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2012 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

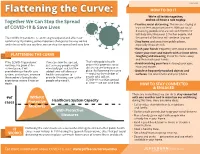

Flattening the Curve: 3/9/2020 We’Re All in This Together, Together We Can Stop the Spread and We All Have a Role to Play

3/23/2020 HOW TO DO IT Flattening the Curve: 3/9/2020 We’re all in this together, Together We Can Stop the Spread and we all have a role to play. • Practice social distancing. This means staying at of COVID-19 & Save Lives least six feet away from others. Without social distancing, people who are sick with COVID-19 will likely infect between 2-3 other people, and The COVID-19 pandemic is continuing to expand and affect our the spread of the virus will continue to grow. community. By making some important changes to the way we live • Stay home and away from public places, and interact with one another, we can stop the spread and save lives. especially if you are sick. • Wash your hands frequently with soap and water. • Cover your nose and mouth with a tissue when FLATTENING THE CURVE coughing and sneezing, throw the tissue away and then wash your hands. If the COVID-19 pandemic If we can slow the spread, That’s why public health orders that promote social • Avoid touching your face including your eyes, continues to grow at the just as many people might nose and mouth. current pace, it will eventually get sick, but the distancing are being put in overwhelm our health care added time will allow our place. By flattening the curve • Disinfect frequently touched objects and system, and in-turn, increase health care system to — reducing the number of surfaces, like door knobs and your phone. the number of people who provide lifesaving care to the people who will get experience severe illness or people who need it. -

The Jihadi Threat: ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and Beyond

THE JIHADI THREAT ISIS, AL QAEDA, AND BEYOND The Jihadi Threat ISIS, al- Qaeda, and Beyond Robin Wright William McCants United States Institute of Peace Brookings Institution Woodrow Wilson Center Garrett Nada J. M. Berger United States Institute of Peace International Centre for Counter- Terrorism Jacob Olidort The Hague Washington Institute for Near East Policy William Braniff Alexander Thurston START Consortium, University of Mary land Georgetown University Cole Bunzel Clinton Watts Prince ton University Foreign Policy Research Institute Daniel Byman Frederic Wehrey Brookings Institution and Georgetown University Car ne gie Endowment for International Peace Jennifer Cafarella Craig Whiteside Institute for the Study of War Naval War College Harleen Gambhir Graeme Wood Institute for the Study of War Yale University Daveed Gartenstein- Ross Aaron Y. Zelin Foundation for the Defense of Democracies Washington Institute for Near East Policy Hassan Hassan Katherine Zimmerman Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy American Enterprise Institute Charles Lister Middle East Institute Making Peace Possible December 2016/January 2017 CONTENTS Source: Image by Peter Hermes Furian, www . iStockphoto. com. The West failed to predict the emergence of al- Qaeda in new forms across the Middle East and North Africa. It was blindsided by the ISIS sweep across Syria and Iraq, which at least temporarily changed the map of the Middle East. Both movements have skillfully continued to evolve and proliferate— and surprise. What’s next? Twenty experts from think tanks and universities across the United States explore the world’s deadliest movements, their strate- gies, the future scenarios, and policy considerations. This report reflects their analy sis and diverse views. -

Muslims in the War on Terror Discourse

2014/15 29 ! Reading Power: Muslims in the War on Terror Discourse Dr. Uzma Jamil Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the International Centre for Muslim and Non- Muslim Understanding at the University of South Australia. ISLAMOPHOBIA STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 2, NO. 2, FALL 2014, PP. 29-42. Published by: Islamophobia Research and Documentation Project, Center for Race and Gender, University of California, Berkeley. Disclaimer: Statements of fact and opinion in the articles, notes, perspectives, etc. in the Islamophobia Studies Journal are those of the respective authors and contributors. They are not the expression of the editorial or advisory board and staff. No representation, either expressed or implied, is made of the accuracy of the material in this journal and ISJ cannot accept any legal responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions that may be made. The reader must make his or her own evaluation of the accuracy and appropriateness of those materials. 30 2014/15 Reading Power: Muslims in the War on Terror Discourse Dr. Uzma Jamil Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the International Centre for Muslim and Non-Muslim Understanding at the University of South Australia ABSTRACT: This paper analyzes the relationship between Muslims and the west defined at a particular moment in post 9/11 America and the war on terror context through a conversation in the novel The Submission (2011) by Amy Waldman. It critiques the construction of knowledge about Muslims and how this knowledge functions as part of a hegemonic discourse of Orientalism. The novel is about a public competition for an architectural design for a memorial marking the site of the World Trade Centre attacks in New York City. -

Pandemic.Pdf.Pdf

1 PANDEMICS: Past, Present, Future Published in 2021 by the Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Education for Peace and Challenges & Opportunities Sustainable Development, 35 Ferozshah Road, New Delhi 110001, India © UNESCO MGIEP This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike Coordinating Lead Authors: 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ ANANTHA KUMAR DURAIAPPAH by-sa/3.0/ igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be Director, UNESCO MGIEP bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http:// www.unesco.org/openaccess/terms-use-ccbysa-en). KRITI SINGH Research Officer, UNESCO MGIEP The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they Lead Authors: NANDINI CHATTERJEE SINGH are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Senior Programme Officer, UNESCO MGIEP The publication can be cited as: Duraiappah, A. K., Singh, K., Mochizuki, Y. YOKO MOCHIZUKI (Eds.) (2021). Pandemics: Past, Present and Future Challenges and Opportunities. Head of Policy, UNESCO MGIEP New Delhi. UNESCO MGIEP. SHAHID JAMEEL Coordinating Lead Authors: Director, Trivedi School of Biosciences, Ashoka University Anantha Kumar Duraiappah, Director, UNESCO MGIEP Kriti Singh, Research Officer, UNESCO MGIEP Lead Authors: Nandini Chatterjee Singh, Senior Programme Officer, UNESCO MGIEP Contributing Authors: CHARLES PERRINGS Yoko Mochizuki, Head of Policy, UNESCO MGIEP Global Institute of Sustainability, Arizona State University Shahid Jameel, Director, Trivedi School of Biosciences, Ashoka University W. -

2021-03-15 No Clear Significant Benefit to Lockdowns

Two minutes with the Justice Centre In other words, locking people down made no difference. No clear, significant Meanwhile in Ontario, one of the province’s former chief medical officers sent an open letter to Premier Doug Ford in benefit to lockdowns January, saying: “Lockdown was never part of our planned pandemic response, nor is it supported by strong science.” March 15, 2021 Dr. Richard Schabas had been Ontario CMO for ten years, and was personally involved with the 2003 SARS crisis, as chief of staff at York Central Hospital. Schabas wrote in support of North York MPP Roman Baber, who had been expelled from the Ontario Conservative caucus after writing to Ford that: “The lockdown isn’t working. It’s causing an avalanche of suicides, overdoses, bankruptcies, divorces and takes an immense toll on children.” Schabas noted Baber had been correct in his criticisms and in his call for an end to the Ontario lockdowns. Lockdowns are said to be necessary to slow the spread of Covid, so that health systems are not overwhelmed. “Lockdowns more lethal than Covid” -Dr. Modry Not everybody agrees the health system is in danger, however. In Alberta a highly qualified cardiovascular surgeon, Sometimes it seems a rational discussion of lockdowns is Dr. Dennis Modry, questioned Premier Kenney’s rationale for beyond Canadians. However, more and more the credible continued lockdowns in a December open letter. “We are voices are confirming what has been suspected from the start: nowhere close to overwhelming our healthcare system. As of Lockdowns don’t work and are actually harmful. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5.