REMAKING of JEWISH SOCIALITY in CONTEMPORARY POLAND: HAUNTING LEGACIES, GLOBAL CONNECTIONS. a Thesis Submitted to the University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

Slavery Today INT 8/8/03 12:08 PM Page 1

AI Slavery Today INT 8/8/03 12:08 PM Page 1 Slavery Today Auriana Ojeda, Book Editor Daniel Leone, President Bonnie Szumski, Publisher Scott Barbour, Managing Editor Helen Cothran, Senior Editor San Diego • Detroit • New York • San Francisco • Cleveland New Haven, Conn. • Waterville, Maine • London • Munich AI Slavery Today INT 8/8/03 12:08 PM Page 2 © 2004 by Greenhaven Press. Greenhaven Press is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Greenhaven® and Thomson Learning™ are trademarks used herein under license. For more information, contact Greenhaven Press 27500 Drake Rd. Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535 Or you can visit our Internet site at http://www.gale.com ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems—without the written permission of the publisher. Every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyrighted material. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Slavery today / Auriana Ojeda, book editor. p. cm. — (At issue) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7377-1614-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-7377-1613-4 (lib. bdg. : alk. paper) 1. Slavery. 2. Slave labor. I. Ojeda, Auriana, 1977– . II. At issue (San Diego, Calif.) HT871.S55 2004 306.3'62—dc21 2003051617 Printed in the United States of America AI Slavery Today INT 8/8/03 12:08 PM Page 3 Contents Page Introduction 4 1. -

In Their Own Words: Voices of Jihad

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as CHILD POLICY a public service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and PUBLIC SAFETY effective solutions that address the challenges facing SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY the public and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. in their own words Voices of Jihad compilation and commentary David Aaron Approved for public release; distribution unlimited C O R P O R A T I O N This book results from the RAND Corporation's continuing program of self-initiated research. -

Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 11 Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Transatlantic Security Studies, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Kathleen Bailey presents evidence of forgeries to the press corps. Credit: The Washington Times Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference By Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 11 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2012 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

The Jihadi Threat: ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and Beyond

THE JIHADI THREAT ISIS, AL QAEDA, AND BEYOND The Jihadi Threat ISIS, al- Qaeda, and Beyond Robin Wright William McCants United States Institute of Peace Brookings Institution Woodrow Wilson Center Garrett Nada J. M. Berger United States Institute of Peace International Centre for Counter- Terrorism Jacob Olidort The Hague Washington Institute for Near East Policy William Braniff Alexander Thurston START Consortium, University of Mary land Georgetown University Cole Bunzel Clinton Watts Prince ton University Foreign Policy Research Institute Daniel Byman Frederic Wehrey Brookings Institution and Georgetown University Car ne gie Endowment for International Peace Jennifer Cafarella Craig Whiteside Institute for the Study of War Naval War College Harleen Gambhir Graeme Wood Institute for the Study of War Yale University Daveed Gartenstein- Ross Aaron Y. Zelin Foundation for the Defense of Democracies Washington Institute for Near East Policy Hassan Hassan Katherine Zimmerman Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy American Enterprise Institute Charles Lister Middle East Institute Making Peace Possible December 2016/January 2017 CONTENTS Source: Image by Peter Hermes Furian, www . iStockphoto. com. The West failed to predict the emergence of al- Qaeda in new forms across the Middle East and North Africa. It was blindsided by the ISIS sweep across Syria and Iraq, which at least temporarily changed the map of the Middle East. Both movements have skillfully continued to evolve and proliferate— and surprise. What’s next? Twenty experts from think tanks and universities across the United States explore the world’s deadliest movements, their strate- gies, the future scenarios, and policy considerations. This report reflects their analy sis and diverse views. -

Muslims in the War on Terror Discourse

2014/15 29 ! Reading Power: Muslims in the War on Terror Discourse Dr. Uzma Jamil Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the International Centre for Muslim and Non- Muslim Understanding at the University of South Australia. ISLAMOPHOBIA STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 2, NO. 2, FALL 2014, PP. 29-42. Published by: Islamophobia Research and Documentation Project, Center for Race and Gender, University of California, Berkeley. Disclaimer: Statements of fact and opinion in the articles, notes, perspectives, etc. in the Islamophobia Studies Journal are those of the respective authors and contributors. They are not the expression of the editorial or advisory board and staff. No representation, either expressed or implied, is made of the accuracy of the material in this journal and ISJ cannot accept any legal responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions that may be made. The reader must make his or her own evaluation of the accuracy and appropriateness of those materials. 30 2014/15 Reading Power: Muslims in the War on Terror Discourse Dr. Uzma Jamil Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the International Centre for Muslim and Non-Muslim Understanding at the University of South Australia ABSTRACT: This paper analyzes the relationship between Muslims and the west defined at a particular moment in post 9/11 America and the war on terror context through a conversation in the novel The Submission (2011) by Amy Waldman. It critiques the construction of knowledge about Muslims and how this knowledge functions as part of a hegemonic discourse of Orientalism. The novel is about a public competition for an architectural design for a memorial marking the site of the World Trade Centre attacks in New York City. -

Inner Light – Good and Evil – Open and Hidden

2 n d e d n © T G 2 0 2 1 £ 1 0 v i a 1 b i l d e r b e r g . o extracts companion to The Siege Of Heaven with my thoughts on solutions – ed.on Heaven The solutions – with my thoughts Siege Of toextracts companion under guise of a never-ending pandemic, modelled on their never ending war on terror. terror. endingwar never pandemic, theiron modelled on a guiseofunder never-ending legallyandtaken up,overbeingboughtfreedom as mediaFood is thought for all ismySo career!this secretRothschilds Victor on Fifth ‘Thesee Man’ Please financially. Since the Anglo-Zionist empire has been defeated militarilyinMiddle defeated Russia, been East Anglo-Zionist by empire hasthe Sincethe eyecrushing their journalism in the they’ve own population, to subduing their turned surveillance bringing to the authoritarian state west, – the China Assange Julian ofperson Portland Communications boss George Pascoe-Watson with Lord with and Bethell who funded Pascoe-Watson Portland George Communications boss were leadershipcampaign Tory 2019 Hancock’s Matthealth managed UK secretary the plandemic.steeringCovidthe start of ministerial discussions from Generally short extracts from longer works - published in the midst of November 2020’s published - November 2020’s longer in the midst of extracts works Generally from short Pharma Banking, Bigchum lobbyists Arms, It becomes boguslight’. ‘lockdown clear UK r g 2 n d e d n © T G 2 0 2 1 £ 1 0 v i a 2 b i l All reserved rights d ISBN 0 9528070 8 4 e The SiegeThe Of Reader Heaven Copyright Tony Gosling 2021 Tony Copyright a magazine,a newspaper or broadcast r Printed and bound in the USA by lulu.com andPrinted the bound in USA b Address: 17-25, Jamaica Street, Bristol, BS2 8JP The moral rightsThe author of the been have asserted e post-medieval articles on occult political and spiritual power r First published in published BritainFirst Great in by Gosling publishing 2021 g A catalogue for this record book is available the Library from British A pleased make necessary to the arrangements at earliest the opportunity. -

Click Here to Read the February 2017 Jjmm

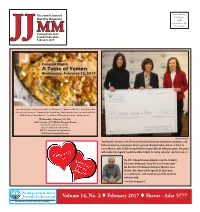

The Jewish Journal Non-Profit Org. U.S. Postage Monthly Magazine PAID Youngstown, OH Permit #607 MMYoungstown Area Jewish Federation JJ February 2017 Photo/Tony Mancino Andi Baroff, a member of the Thomases Family Endowment distribution committee, and Deborah Grinstein, endowment director, present Maraline Kubik, director of Sister Je- rome’s Mission, with $7,500 to benefit Sister Jerome’s Mission College program. The grant will enable the program to admit another student for spring semester. See story on p. 21. The JCC’s Schwartz Judaica Library is now the Schwartz Holocaust, Media and Library Resource Center, under the direction of Federation Holocaust Educator Jesse McClain. The Center will be open M, W, and F from noon until 2 p.m., with more hours possible thanks to volunteer help. See story on page 24. Youngstown Area Jewish Federation Volume 14, No. 2 t February 2017 t Shevat - Adar 5777 THE STRENGTH OF A PEOPLE. THE POWER OF COMMUNITY. Commentary Jerusalem institutions could close if U.N. resolution is implemented By Rafael Medoff/JNS.org raeli author Yossi Klein Halevi told JNS. on the Mount of Olives,” Washington, those sections of Jerusalem would cut org. “So the recent U.N. resolution has D.C.-based attorney Alyza Lewin told across Jewish denominational lines, af- WASHINGTON—The human con- criminalized me and my family as oc- JNS.org. “Does the U.N. propose to ban fecting Orthodox and non-Orthodox sequences of implementing the recent cupiers.” Jews from using the oldest and largest institutions alike. United Nations resolution -

Unified Conspiracy Theory - Rationalwiki

Unified Conspiracy Theory - RationalWiki http://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Unified_Conspiracy_Theory Unified Conspiracy Theory From RationalWiki The Unified Conspiracy Theory is a conspiracy theory, popular with Some dare call it some paranoids, that all of reality is controlled by a single evil entity that has it in for them. It can be a political entity, like "The Illuminati", or a Conspiracy metaphysical entity, like Satan, but this entity is responsible for the creation and management of everything bad. The Church of the SubGenius has adopted this notion as fundamental dogma. Michael Barkun coined the term "superconspiracy" to refer the idea that the world is controlled by an interlocking hierarchy of conspiracies. Secrets revealed! Similarly, Michael Kelly, a neoconservative journalist, coined the term America Under Siege "fusion paranoia" in 1995 to refer to the blending of conspiracy theories CW Leonis of the left with those of the right into a unified conspiratorial Doug Rokke [1] worldview. Guillotine List of conspiracy theories This was played with in the Umberto Eco novel Foucault's Pendulum , in Majestic 12 which the characters make up a conspiracy theory like this...except it Pravda.ru turns out to be true. Shakespeare authorship Society of Jesus Tupac Shakur Contents v - t - e (http://rationalwiki.org /w/index.php?title=Template:Conspiracynav& action=edit) 1 See also 1.1 (In)Famous proponents 2 External links 3 Footnotes See also List of Conspiracy Theories Maltheism Crank magnetism (In)Famous proponents David Icke Alex Jones Lyndon LaRouche Jeff Rense 1 of 2 7/19/2012 8:24 PM Unified Conspiracy Theory - RationalWiki http://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Unified_Conspiracy_Theory External links Flowchart guide to the grand conspiracy (http://farm4.static.flickr.com /3048/2983450505_34b4504302_o.png) Conspiracy Kitchen Sink (http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/ConspiracyKitchenSink) , TV Tropes Footnotes 1. -

Feeding New Immigrants in Their Time of Need Michio Nagata/Bridgesforpeace.Com

Bridges for Peace in Action Vol. #770420A April 2020 Feeding New Immigrants in Their Time of Need Michio Nagata/bridgesforpeace.com “WE KNEW YOU WOULD COME. You have helped us in the sector lost their jobs. Within a mere three weeks, un- before and we knew you would again. We recognize you. employment has more than quadrupled, skyrocketing from You are the people who help. You are the people who bless. 3.6% to 22.7%, with nearly 800,000 Israelis registering for HaShem will bless you.” unemployment since the beginning of the month. Tzvi Khaute’s eyes were pools of tears as he looked at The Bnei Menashe and Chinese Jews from Kaifeng are the pallets of food a team from Bridges for Peace was busy among those who now face a bleak future without an income unpacking—food that would help feed Tzvi’s community, to support their families. More than 200 Bnei Menashe olim the Bnei Menashe. The Bnei Menashe (literally “Sons of (immigrants) have now Menashe”) are descendants of one of the Ten Lost Tribes lost their jobs. Moreover, of Israel living in northeastern India and have steadily been many Chinese Jewish fulfilling their dream of many generations to return to the olim working in the tour- Land from which they were exiled more than 27 centuries ism industry are now un- ago—with the help of Shavei Israel, an organization helping expectedly unemployed Jewish descendants reclaim their roots. as hotels, tour agencies and popular tourist Tzvi made aliyah (immigrated to Israel) 20 years ago and attractions have shut made a life for himself and his family in the “Promised Land,” their doors. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881-1940 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6gn7b51j Author Myers, Eric Dennis Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881 - 1940 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Eric Dennis Myers 2013 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881 - 1940 by Eric Dennis Myers Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Joan Waugh, Chair The dissertation is a historical biography of Smedley Darlington Butler (1881-1940), a decorated soldier and critic of war profiteering during the 1930s. A two-time Congressional Medal of Honor winner and son of a powerful congressman, Butler was one of the most prominent military figures of his era. He witnessed firsthand the American expansionism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, participating in all of the major conflicts and most of the minor ones. Following his retirement in 1931, Butler became an outspoken critic of American intervention, arguing in speeches and writings against war profiteering and the injustices of expansionism. His critiques represented a wide swath of public opinion at the time – the majority of Americans supported anti-interventionist policies through 1939. Yet unlike other members of the movement, Butler based his theories not on abstract principles, but on experiences culled from decades of soldiering: the terrors and wasted resources of the battlefield, ! ""! ! the use of the American military to bolster corrupt foreign governments, and the influence of powerful, domestic moneyed interests. -

Genres of Financial Capitalism in Gilded Age America

Reading the Market Peter Knight Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Knight, Peter. Reading the Market: Genres of Financial Capitalism in Gilded Age America. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.47478. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/47478 [ Access provided at 28 Sep 2021 08:25 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reading the Market new studies in american intellectual and cultural history Jeffrey Sklansky, Series Editor Reading the Market Genres of Financial Capitalism in Gilded Age America PETER KNIGHT Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore Open access edition supported by The University of Manchester Library. © 2016, 2021 Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2021 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Johns Hopkins Paperback edition, 2018 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition of this book as folllows: Names: Knight, Peter, 1968– author Title: Reading the market : genres of financial capitalism in gilded age America / Peter Knight. Description: Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, [2016] | Series: New studies in American intellectual and cultural history | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015047643 | ISBN 9781421420608 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781421420615 (electronic) | ISBN 1421420600 [hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 1421420619 (electronic) Subjects: LCSH: Finance—United States—History—19th century | Finance— United States—History—20th century.